To analyze changes in performance indicators five years after Portugal joined the Stent for Life (SFL) initiative.

MethodsNational surveys were carried out annually over one-month periods designated as study Time Points between 2011 (Time Zero) and 2016 (Time Five). In this study, 1340 consecutive patients with suspected ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) who underwent coronary angiography, admitted to 18 24/7 primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centers, were enrolled.

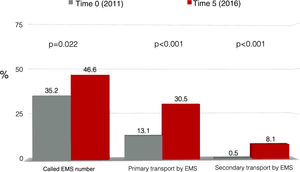

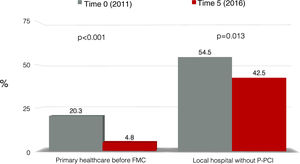

ResultsThere was a significant reduction in the proportion of patients who attended primary healthcare centers (20.3% vs. 4.8%, p<0.001) and non-PCI-capable centers (54.5% vs. 42.5%, p=0.013). The proportions of patients who called 112, the national emergency medical services (EMS) number (35.2% vs. 46.6%, p=0.022) and of those transported via the EMS to a PCI-capable center (13.1% vs. 30.5%, p<0.001) increased. The main improvement observed in timings for revascularization was a trend toward a reduction in patient delay (114 min in 2011 vs. 100 min in 2016, p=0.050). System delay and door-to-balloon time remained constant, at a median of 134 and 57 min in 2016, respectively.

ConclusionDuring the lifetime of the SFL initiative in Portugal, there was a positive change in patient delay indicators, especially the lower proportion of patients who attended non-PCI centers, along with an increase in those who called 112. System delay did not change significantly over this period. These results should be taken into consideration in the current Stent – Save a Life initiative.

Avaliar a evolução dos indicadores de desempenho da Iniciativa Stent for Life (SFL) durante os cinco anos de atividade em Portugal.

MétodosInquéritos nacionais foram feitos anualmente, por períodos de um mês, designados por «Momentos», entre 2011 (Momento Zero) e 2016 (Momento Cinco). Neste estudo, foram incluídos 1340 doentes consecutivos com suspeita de enfarte agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento de ST (STEMI) submetidos a angiografia coronária, admitidos em 18 centros de angioplastia primária (P-PCI) 24/7.

ResultadosObservou-se uma redução significativa da percentagem de doentes que recorreram aos cuidados primários (20,3% versus 4,8%, p<0,001) e centros não PCI (54,5% versus 42,5%, p=0,013). A percentagem de doentes que ligaram para o 112 (INEM) (35,2% versus 46,6%, p=0,022) e transporte de doentes através do INEM para um centro com capacidade de PCI (13,1% versus 30,5%, p<0,001) aumentou. A principal melhoria observada nos intervalos de tempo para a revascularização foi uma tendência à redução do «atraso do doente» (114 minutos em 2011 versus 100 minutos em 2016, p=0,050). O «atraso do sistema» e tempo «porta-balão» (D2B) permaneceram constantes, registando uma mediana de 134 e 57 minutos em 2016, respetivamente.

ConclusãoDurante o período de vigência da iniciativa SFL em Portugal, houve uma evolução positiva dos indicadores de «atraso do doente», nomeadamente a redução da percentagem de pacientes que recorreram a centros não PCI, juntamente com um aumento daqueles que ligaram para o INEM. O «atraso do sistema» ainda não sofreu alterações significativas ao longo deste período, devendo estes resultados ser considerados na estratégia atual do Stent Save a Life (SSL).

The Stent for Life (SFL) initiative was implemented in Europe in 2008.1 Its main objective was to increase timely access to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (P-PCI), in order to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

The SFL initiative supported processes that aimed to improve the organization of existing regional systems and to create new systems that enable better implementation of European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for STEMI treatment. SFL was initially implemented in five countries2 and in 2011, Portugal also joined the initiative.3 There are few projects in medicine with the ambitious goal to reduce mortality. Instead of new drugs or medical devices, this SFL goal was achieved by improving the efficiency and availability of P-PCI, a treatment that had been performed for more than a decade.

SFL set out to increase the number of patients with STEMI treated with P-PCI, aiming to perform 600 P-PCI procedures/year/million population. However, the incidence of STEMI is not the same in all European countries and the goals had to be adjusted according to the national incidence. According to data published by the Portuguese Directorate-General of Health (DGS), the P-PCI/year/million population ratio improved threefold in a decade, increasing from 106 in 2002 to 338 in 2013.4

At the same time, the SFL initiative also aimed to improve the quality of STEMI treatment, by reducing reperfusion time. The difficulties hampering good P-PCI performance vary among countries, so the action plans to implement the initiative were adjusted according to the specific needs and current situation of each country. Considering that the timing variable is one of the main elements affecting mortality and the complexity of the overall process, both educational and logistical, this was a very ambitious project that simultaneously involved patients, their relatives, healthcare professionals and health authorities.

This work aims to describe the action plan defined by the SFL initiative, the programs that were developed within its scope, and the reporting of the main results obtained five years after Portugal joined the initiative.

MethodsIn 2011, a task force was created to discuss the main difficulties hampering good P-PCI performance in Portugal. This group identified three different areas that needed specific interventions: (1) patient population: patients were unable to recognize the symptoms of myocardial infarction (MI), took too long to ask for help and went to the hospital by their own means, instead of calling 112, the national emergency medical services (EMS) number; (2) EMS: the EMS did not directly contact interventional cardiology centers and did not systematically send electrocardiograms (ECGs) to these centers; and (3) hospitals: the performance of hospital networks presented long system delays and the national network included regions that had no 24/7 P-PCI.

In order to overcome these difficulties, various programs were created within each sector. Programs aimed at the patient population were developed under the international SFL slogan ‘Act now. Save a life’. With the help of a communications agency, informative materials, including flyers, posters and videos, were produced to support the campaign. Public figures were invited to be ambassadors and partnerships were set up with the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society, major national companies in different business areas (energy, entertainment, supermarkets, etc.) and local government bodies. During the five-year period, SFL maintained an ongoing campaign in the press and on radio and television.

Programs targeting the EMS firstly aimed to enable the EMS to directly contact centers with P-PCI facilities, send ECGs, and manage secondary transport between hospitals with and without P-PCI facilities. Additionally, an educational program on acute coronary syndromes (ACS) was developed (STEMINEM) that targeted EMS healthcare professionals.

Regarding hospitals, besides meetings aiming to facilitate the implementation of a national 24/7 P-PCI network, an educational program on ACS (STEMICARE), as well as the discussion platform Stent Network Meeting, were introduced targeting emergency department healthcare professionals.

To evaluate the success of this initiative, specific methods were established to enable qualitative assessment of patient and system delays, as well as market and economic assessment studies.

In this study, we analyze the results of SFL activities in Portugal in the five years of the initiative, using a series of annual study Time Points, in which a prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in all P-PCI-capable hospitals in mainland Portugal that were included in the Via Verde Coronária (the national coronary fast-track system). Data on 1340 patients with suspected STEMI of less than 12 hours duration and referred for P-PCI, admitted to 18 Portuguese cardiology centers, were collected during a one-month period each year from 2011 to 2016. All enrolled patients gave their informed consent for P-PCI and data collection by the National Center for Data Collection in Cardiology (CNCDC) of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology (SPC).5

This study aims to compare the results from 2011 (Time 0) and from 2016 (Time 5), in order to assess the evolution of the SFL initiative during the five years of its activities in Portugal.

TimingsFirst medical contact (FMC) was defined as the time of arrival of medical and/or paramedical staff to assist the patient for prehospital care or the time of arrival at a hospital. Patient delay was defined as the time between symptom onset and FMC; it was considered a continuous variable and expressed in min. System delay was defined as the time from FMC to the beginning of reperfusion therapy, with balloon, wiring or mechanical thrombectomy, and was considered a continuous or categorical variable (cut-off value 90 min).

Door-to-balloon time was defined as the time from admission to a P-PCI-capable hospital to reperfusion therapy, and was analyzed as a continuous or categorical variable (cut-off value 60 min). Total ischemic time was defined as the time between symptom onset and reperfusion and was analyzed as a continuous or categorical variable (cut-off value 120 min).

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviation. Normality of data was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and equality of variances was assessed by the Levene test. The Student's t test was used to compare the mean of variables presenting normal distribution or equality of variances (e.g. age). Categorical variables were presented as percentages and proportions were compared by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed, including patient delay and system delay, were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared with the Mann-Whitney U test for two independent samples or the Kruskal-Wallis test for more than two samples.

Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software for Windows version 21.

ResultsData from study Time PointsBetween 2011 and 2016, 1340 patients (mean age 62±13 years, 74.9% male), from 18 national interventional cardiology centers, were enrolled in the Time Points. The demographic data and medical history of these patients are presented in Table 1. There was a trend for an increase in the proportion of diabetic patients since the beginning of the study (16.2% in 2011 vs. 23.2% in 2016, p=0.088). The proportion of patients that called 112, the EMS number, increased significantly (35.2% in 2011 vs. 46.6% in 2016, p=0.022) (Figure 1). A significant reduction was also observed in the proportion of patients who attended healthcare centers without P-PCI (54.5% in 2011 vs. 42.5% in 2016, p=0.013), as well as those who attended primary care centers (20.3% in 2011 vs. 4.8% in 2016, p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Demographic characteristics and medical history of the population included in the Time Points.

| Variable | Time 0 (n=187) | Time 1(n=187) | Time 2 (n=223) | Time 3 (n=256) | Time 4 (n=220) | Time 5 (n=267) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region, % | |||||||

| North | 43.9 | 40.6 | 33.6 | 35.5 | 39.5 | 34.1 | <0.001 |

| Center | 13.4 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 11.6 | |

| LVT | 37.4 | 44.4 | 45.7 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 39.3 | |

| Algarve | 5.3 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 6.4 | |

| Alentejo | 0 | 1.6 | 7.2 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 8.6 | |

| Female gender, % | 21.9 | 17.9 | 27.7 | 20.6 | 26.9 | 25.2 | 0.129 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 62.1 (13.7) | 61.5 (13.2) | 62.6 (13.6) | 60.8 (13.8) | 64.5 (12.3) | 62.7 (13.4) | 0.074 |

| Age>75 years, % | 18.4 | 18.4 | 20.4 | 17.1 | 25.5 | 20.5 | 0.313 |

| Past medical history, % | |||||||

| PCI | 9.9 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 13.1 | 0.877 |

| CABG | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.491 |

| MI | 9.7 | 10.5 | 13.5 | 12.4 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 0.789 |

| Diabetes | 16.2 | 22.1 | 21.2 | 17.6 | 29.1 | 23.2 | 0.025 |

| Diagnosis of STEMI after team activation, % | 92.0 | 93.5 | 87.3 | 87.2 | 91.3 | 90.1 | 0.164 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; LVT: Lisbon and Tagus Valley; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Attendance at a healthcare center without primary percutaneous coronary intervention facilities after symptom onset in patients with myocardial infarction before and after five years of activity of Stent for Life in Portugal. FMC: first medical contact; P-PCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

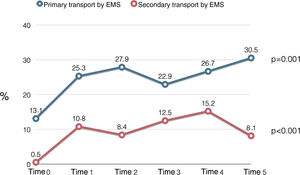

A significant increase was also observed in the proportion of patients whose primary transport was by EMS (13.1% in 2011 vs. 30.5% in 2016, p<0.001), as well as of those whose secondary transport was by EMS (0.5% in 2011 vs. 8.1% in 2016, p<0.001) (Figure 1). Figure 3 presents changes in primary and secondary transport performed by EMS throughout all the Time Points, showing a positive trend over time, except for the percentage of secondary transport in Time 5 (2016).

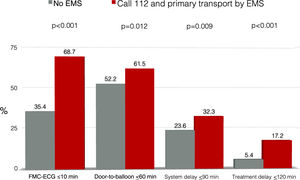

Moreover, patients who called 112 and who were transported to P-PCI facilities by the EMS more often presented delays within the limits set by the ESC and the American College Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines than other patients: FMC-ECG time ≤10 min (68.7% vs. 35.4%, p<0.001); door-to-balloon time ≤60 min (61.5% vs. 52.2%, p=0.012); system delay ≤90 min (32.3% vs. 23.6%, p=0.009); and total ischemic time ≤120 min (17.2% vs. 5.4%, p<0.001) (Figure 4).

Proportions of patients within the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for reperfusion delays. The graphic compares the ideal scenario (calling 112 and primary transport to a center with primary percutaneous coronary intervention) with other scenarios. ECG: electrocardiogram; EMS: emergency medical services; FMC: first medical contact.

Among patients who directly attended healthcare centers with P-PCI facilities, the proportion of patients who arrived by their own means of transport fell (49.4% in 2011 vs. 32.8% in 2016, p=0.016). While the proportion of patients who were transported by the EMS (22.4% in 2011 vs. 48.0% in 2016, p<0.001) rose, the proportion being transported by basic life support ambulance decreased (28.2% in 2011 vs. 15.3% in 2016; p=0.025). Table 2 shows that patient delay and door-to-balloon time, and consequently total ischemic time, were longer in patients who went directly to P-PCI-capable centers by their own means than in those who were transported by the EMS.

Comparison of reperfusion times in patients who directly attended a center with primary percutaneous coronary intervention by their own means and those transported by the emergency medical services.

| Variable | Own means (n=241) | EMS (n=284) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom onset-FMC (patient delay), min | 132.0 (71.0-255.0) | 60.0 (35.0-115.0) | <0.001 |

| FMC-ECG, min | 16.0 (9.0-32.0) | 6.0 (2.0-13.8) | <0.001 |

| Admission to P-PCI hospital-reperfusion (door-to-balloon time), min | 104.0 (75.0-164.0) | 52.0 (30.0-79.0) | <0.001 |

| FMC-reperfusion (system delay), min | 104.0 (75.0-164.0) | 103.0 (82.0-135.0) | 0.764 |

| Symptom onset-reperfusion (total ischemic time), min | 257.5 (172.8-445.0) | 180.0 (140.0-256.5) | <0.001 |

Results are presented as median and interquartile range.

ECG: electrocardiogram; EMS: emergency medical services; FMC: first medical contact; P-PCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

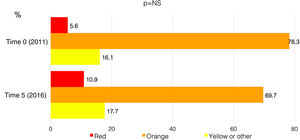

Concerning the Manchester triage system, which attributes clinical priority for attendance of patients admitted to a hospital unit, the proportion of patients who did not receive a red or orange code (needing immediate or very urgent assistance) within 10 min of admission remained constant throughout the Time Points (16.1% of patients received a yellow or green code in 2011 vs. 17.7% in 2016) (Figure 5).

Proportions of patients assigned different priorities according to the Manchester triage system, before and after five years of activity of Stent for Life in Portugal. Red: emergency, requires immediate intervention; orange: very urgent, needing an intervention within 10 min; yellow or other: urgent or less urgent, can wait 60 min or more for an intervention.

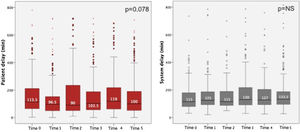

During the study, no significant change was observed in patient delay, system delay or door-to-balloon time (Table 3 and Figure 6). Although there was a trend for a reduction in patient delay (114 min in 2011 vs. 100 min in 2016, p=0.050), a trend was also observed for longer system delay (115 min in 2011 vs. 134 min in 2016, p=0.059).

Reperfusion times before and after five years of activity of Stent for Life in Portugal.

| Variable | Statistic | Time 0 (n=187) | Time 5 (n=267) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom onset-FMC (patient delay), min | Median (IQR) | 113.5 (63.5-211.5) | 100.0 (50.5-190.0) | 0.050 |

| FMC-ECG, min | Median (IQR) | 16.0 (8.0-39.0) | 15.0 (6.0-36.5) | 0.482 |

| Time from FMC to ECG ≤10 min | % | 32.7 | 40.6 | 0.128 |

| Admission to P-PCI hospital-reperfusion (door-to-balloon time), min | Median (IQR) | 54.0 (30.0-99.5) | 54.0 (30.0-95.0) | 0.812 |

| Door-to-balloon ≤60 min | % | 55.7 | 57.0 | 0.834 |

| FMC-reperfusion (system delay), min | Median (IQR) | 115.0 (79.0-179.5) | 133.5 (95.0-188.0) | 0.059 |

| System delay ≤90 min | % | 31.6 | 21.8 | 0.041 |

| Symptom onset-reperfusion (total ischemic time), min | Median (IQR) | 250.0 (178.0-430.0) | 270.0 (182.0-408.0) | 0.844 |

| Total ischemic time ≤120 min | % | 8.2 | 7.8 | 1.000 |

ECG: electrocardiogram; FMC: first medical contact; IQR: interquartile range; P-PCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Although at the beginning of the millennium the distribution of P-PCI centers and road networks in Portugal were acceptable, the country had one of the lowest rates of P-PCI implementation in Europe,6 which led the SPC to join the SFL initiative.3 Subsequently, between 2001 and 2013, the rate of P-PCI/million population tripled.7

The aim of the SFL initiative was quantitative, with the aim that ideally 600 P-PCI/year/million population would be performed.8 The SFL Portugal task force also added a qualitative aim, as it considered that treating a larger number of patients with P-PCI was as important as treating them faster. To monitor these objectives, the Time Points analysis was introduced, aiming to assess changes in quality indicators over time.3

Total ischemic time is the sum of patient delay (from symptom onset to FMC) and system delay (from FMC to P-PCI). A total ischemic time longer than four hours has been identified as an independent indicator of mortality within a year of STEMI.9,10 Although the initial focus was on door-to-balloon time, patient delay has been recently given more importance, as it is during the first two hours that the highest incidence of fatal arrhythmias is recorded. Reducing patient delay is not dependent on the direct action of healthcare professionals, but rather depends mainly on the implementation of educational campaigns and on the support of the bodies that oversee healthcare services.

Considering hard endpoints (patient delay, system delay and door-to-balloon time) throughout the five years of this study, it could be said that the SFL initiative in Portugal was unsuccessful, because there were no significant changes in any of these endpoints. However, for a short- to medium-term evaluation of the initiative, these endpoints are not good indicators. More specific indicators, such as the proportions of patients who called the EMS number, went to healthcare centers without P-PCI facilities by their own means or were primarily and/or secondarily transported by EMS, are more sensitive ways to assess whether the SFL initiative led to positive changes.

It is also important to understand why the hard endpoints did not improve during the first years of the initiative. As stated above, in less than ten years the number of P-PCI/year/million population in Portugal tripled,4 meaning that patients living in peripheral regions with less access to hospitals were also included. Inevitably, these patients will have a longer total ischemic time than those who live in large cities closer to hospitals, which will worsen the mean patient delay. At the same time, improvements in prehospital management and patient transport mean that system delay also worsens, because it is timed starting from FMC, even though it may also mean a substantial improvement in the system itself.

If Portugal's performance in the mid-2000s6 is compared with the current situation, there has been a very positive development, as the country had very poor indicators and now is within the European average, alongside Spain, France, Belgium, and the UK11. In addition to the increase in P-PCI procedures, there was also significant progress in the indicators that demonstrate a positive effect of the SFL initiative. The proportion of patients requesting medical assistance by calling 112 increased significantly (by 11.4% in five years). A 12% reduction was also observed in the proportion of patients who attended healthcare without P-PCI facilities by their own means.

It is worth mentioning that, even for patients who directly attended P-PCI-capable hospitals, those who were transported by the EMS were treated significantly earlier than those who arrived by their own means. Door-to-balloon time was significantly shorter in patients who were transported by EMS (a median of 52.0 min less than for patients who arrived by their own means) and this is reflected in earlier P-PCI. These data highlight the less efficient response that emergency services are able to provide for patients that arrive by their own means.

It is important to note the proportion of patients who received a yellow or green Manchester triage code (16.1% in 2011 vs. 17.7% in 2016). This problem is not exclusive to Portugal12 but is also seen in other countries.13 It should be remembered that our study population consisted of patients suspected of having STEMI with less than 12 hours duration and referred for P-PCI. The SFL initiative recommended that a cardiopulmonary technician should always be available at hospital emergency departments to ensure that all patients with thoracic or upper abdominal pain undergo an ECG, to diagnose all STEMI cases that are not immediately detected by the Manchester protocol.

Prehospital transport plays an essential part in the performance of the coronary fast-track system. Between 2011 and 2016, there were significant increases in the proportions of patients who were primarily transported by the EMS (13.1% in 2011 vs. 30.5% in 2016; p=0.001) and in secondary transport, which barely existed in 2011 (0.5%) but increased to 15.2% in 2015. The EMS are responsible for prehospital emergency transport. During the SFL initiative, the EMS were also responsible for the secondary transport of patients in the coronary fast-track system. In 2014, the Ministry of Health reviewed this arrangement and decided that hospitals would be primarily responsible for managing secondary transport and the EMS were only to be used in situations in which hospitals could not carry out this function. Thus, in 2016, there was a decrease in secondary transport performed directly by the EMS (15.2% in 2015 vs. 8.1% in 2016). Currently, hospitals are facing difficulties in organizing and managing an efficient transport system, which is one of the barriers that the SFL task force brought to the attention of the responsible authorities.

Although a public educational campaign was conducted to increase awareness of the symptoms of MI and the need to ask for help by calling 112 (the SFL initiative ‘Act Now. Save a Life’),14 patient delay did not decrease significantly during the five years of the campaign. As mentioned above, these numbers were obtained in patients who had progressively better access to P-PCI. At all events, there was no significant progress in reducing time before FMC, and it is important to analyze the factors that were most strongly associated with this delay and to try and design campaigns and actions targeting these populations. Previous studies showed that older age and symptom onset at night were associated with longer patient delay.14 On the other hand, asking for help by calling 112 and transport by the EMS were associated with shorter patient delay.14

Although door-to-balloon time is associated with mortality,15,16 this indicator is only a small part of total ischemic time. In Portugal, door-to-balloon time is within the range recommended by the guidelines,17–19 but most patients were registered in the healthcare system earlier, as half of them attended hospitals without P-PCI facilities and needed secondary transport, which inevitably meant longer total ischemic times.20

For a long time, door-to-balloon time was one of the main indicators of quality of P-PCI programs. However, in recent years it has been observed that shorter door-to-balloon time is not followed by decreased mortality,21–23 and the US Department of Health and Human Services has decided to remove door-to-balloon time from Value-Based Purchasing algorithms, as hospitals currently report essentially equal performance on door-to-balloon time without room for significant improvement, so it has no value for estimating financing metrics.24 In addition, after observing that more than 75% of non-transferred patients were treated in less than 90 min, the Door-to-Balloon Alliance25 in the US launched a new program, Sustain the Gain, which aimed to maintain the good performance of hospitals treating STEMI.26,27

It has been pointed out that focusing on reducing door-to-balloon time may lead to misdiagnoses, increasing the number of false positives, which may negatively impact efficiency, cause burn-out of hospital teams, consume resources that may be needed in other sectors, and increase costs.28 Some authors report that false positive rates vary between 24% and 36%.29–31 In Portugal, the false positive rate was approximately 10% in the Time Points, which is markedly lower than reported values.

Door-to-balloon time, one of the components of total ischemic time, may not be a good quality indicator. The reason that decreasing it is not followed by reductions in mortality may be because patients often wait before asking for help, which may lead to their death before P-PCI. Since this important factor is not used in the estimation of door-to-balloon time, the effect of door-to-balloon time on reducing mortality may be misinterpreted. The latest ESC guidelines also removed door-to-balloon time as a quality indicator.19

System delay also remained high, with no significant reduction being observed over the years. This was to be expected during the implementation phase of the initiative, as with an increasing proportion of patients calling the EMS number and receiving a prompt response, total ischemic time started earlier. Reductions in system delay are only to be expected at a more mature stage of the SFL initiative. Currently, the factors associated with longer system delay are age >75 years, attendance at a hospital without P-PCI facilities, not calling 112, and patient origin from the Center region.32 For cases in which P-PCI is not possible within 120 min after FMC, fibrinolysis continues to have an important role. Based on randomized studies, the guidelines recommend coronary angiography and possibly angioplasty 3-24 hours after fibrinolysis.33–35

Data collected during the SFL initiative helped in the implementation of various educational programs targeting patients and healthcare professionals, aiming to improve overall system performance.

Under the aegis of the Stent Network Meeting platform, centers with P-PCI met with referral centers, general practitioners, representatives of the EMS and local authorities to discuss and present specific proposals for their centers. These meetings took place in most national centers and enabled the SFL task force to better understand the overall national situation and centers to gain a clearer idea of their own conditions.

In our opinion, educational programs for healthcare professionals have been one of the most important tools, not only to improve knowledge of ACS, but also to facilitate exchange of experiences among the different professionals who are part of the system. STEMINEM targets EMS professionals and STEMICARE targets those working in emergency departments.

To promote preventive and educational actions targeting the young, a partnership was established with the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society, to teach the main aims of the SFL to elementary school students, through the Healthy Generation program.

The studies that have been conducted are based on patients diagnosed with STEMI admitted to hospitals with P-PCI facilities and do not reflect the overall picture of patients with MI, particularly those who have no access to P-PCI.36 Ideally, patients should be treated with P-PCI, but system times must be assessed and monitored to enable the best treatment to be provided to each patient and to determine whether P-PCI is being performed after the period during which this treatment has proved to be better than fibrinolysis.

Now that the SFL initiative has ended, its replacement, Stent – Save a Life (SSL), will extend monitoring to centers without P-PCI facilities, aiming to improve assessment of STEMI patients and to include patients with high-risk non-STEMI.37 SPC registries may be important tools for this goal.

ConclusionDuring the lifetime of the SFL initiative in Portugal, there were positive changes in indicators of patient delay, including lower proportions of patients who resorted to primary health centers and local hospitals without P-PCI facilities, along with an increase in the proportion of those who called the EMS number. System delay did not significantly change over this period. These results should be taken into consideration in the future strategy of the SSL, particularly in strengthening current educational programs aiming to shorten system delays.

Centers participating in the Stent for Life initiative, Portugal, sponsored by the Portuguese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention (APIC):

Hospital Vila Real (Henrique Cyrne Carvalho, MD and Paulino Sousa), Hospital Braga (João Costa, MD), Hospital S. João (João Carlos Silva, MD), Hospital Santo António (Henrique Cyrne Carvalho, MD), Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia (Vasco Gama Fernandes, MD), Hospital de Viseu (João Pipa, MD), Centro Hospitalar de Coimbra (Marco Costa, MD and Vitor Matos, MD), Hospital de Leiria (João Morais, MD), Hospital Fernando da Fonseca (Pedro Farto e Abreu, MD), Hospital de Santa Maria (Pedro Canas da Silva, MD), Hospital Santa Cruz (Manuel Almeida, MD), Hospital de Santa Marta (Rui Ferreira, MD), Hospital Curry Cabral (Luis Morão, MD), Hospital Pulido Valente (Pedro Cardoso, MD), Hospital Garcia de Orta (Hélder Pereira, MD), Hospital Setúbal (Ricardo Santos, MD), Hospital de Évora (Lino Patrício, MD and Renato Fernandes, MD), Hospital de Faro (Victor Brandão, MD).

FundingThe authors state that they have no funding to declare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.