Kawasaki disease (KD) is a systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology, which is the main cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed countries. The main complications result from the development of coronary aneurysms which can lead to ischemic heart disease.

We present the case of a teenage boy with a diagnosis of KD at the age of seven. He was treated with gammaglobulin and aspirin and echocardiographic evaluation in the acute phase was apparently normal. At the age of 11, he developed chest pain and exertional dyspnea. Nuclear perfusion scans with exercise revealed hypoperfusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) and right coronary artery (RCA) territories. Cardiac catheterization showed occlusion of the proximal segments of both arteries. He underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery (internal mammary artery bypass graft to the LAD and saphenous vein graft to the RCA), with a good clinical result.

This case report highlights the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of KD and regular cardiological follow-up, bearing in mind the potential late complications of this pediatric disease.

A doença de Kawasaki (DK) é uma vasculite sistémica, de etiologia desconhecida, constituindo a principal causa de cardiopatia adquirida em idade pediátrica em países desenvolvidos. As principais complicações resultam do aparecimento de aneurismas coronários que podem evoluir para doença coronária isquémica.

Apresenta-se o caso clínico de um adolescente com diagnóstico de DK aos 7 anos. Efetuou terapêutica com imunoglobulina e ácido acetilsalicílico e a avaliação ecocardiográfica na fase aguda foi aparentemente normal. Aos 11 anos de idade desenvolveu quadro de angor e dispneia de esforço. A cintigrafia de perfusão miocárdica com prova de esforço revelou hipoperfusão dos territórios correspondentes às artérias descendente anterior esquerda (DA) e coronária direita (CD). O cateterismo cardíaco demonstrou oclusão dos segmentos proximais de ambas as artérias. Foi submetido a cirurgia de revascularização coronária (artéria mamária interna para a DA e veia safena interna para a CD) com boa evolução clínica e desaparecimento das alterações isquémicas na cintigrafia.

Este caso clínico vem alertar para a importância do diagnóstico e terapêutica atempados e seguimento posterior na DK, salientando-se a potencial gravidade das complicações cardiovasculares a longo prazo, desta doença pediátrica.

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology which principally affects children and occasionally adolescents. It is the main cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed countries.1

Diagnosis is based on the classical clinical criteria of fever persisting at least five days and the presence of at least four of the following signs: changes in extremities, polymorphous exanthem, bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudate, changes in lips and oral cavity, and cervical lymphadenopathy (>1.5cm diameter).2 Incomplete KD should be considered in all children with unexplained fever for more than five days associated with two or three of the principal clinical features of KD; it is more frequent in young infants. Laboratory findings are non-specific, but they may help confirm the diagnosis, particularly in cases of incomplete KD.1

The main complications are cardiovascular; coronary aneurysms are found in 15–25% of untreated children, although this can be reduced to 5% by administration of immunoglobulin in the first ten days of the disease.1 The aneurysms may undergo various alterations: they may regress, stay unchanged, progress to stenotic or obstructive lesions (with or without recanalization or development of collateral vessels) and, very rarely, rupture, develop new lesions, or expand.3 Stenosis of adjacent arteries can lead to ischemic coronary disease, myocardial infarction or sudden death.1

Diagnosis of KD is a challenge, requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion; delay in diagnosis can lead to serious cardiovascular sequelae.

Case reportWe present the case of a boy with a diagnosis of KD at the age of seven, in the context of fever of over five days’ duration, exanthem of the palms and soles, edema of the face and extremities, cervical lymphadenomegaly, and abdominal distension. Laboratory tests revealed elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and thrombocytosis. Two weeks after disease onset, he was treated with IV gammaglobulin and aspirin, which was maintained for two months. Echocardiographic evaluation two weeks after onset of fever showed no alterations. He was followed in the outpatient pediatric clinic for three years, during which he remained asymptomatic; he was not referred for pediatric cardiology consultations, and echocardiography was not repeated.

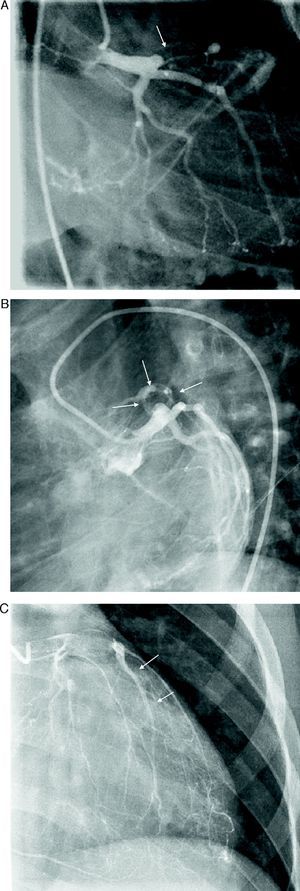

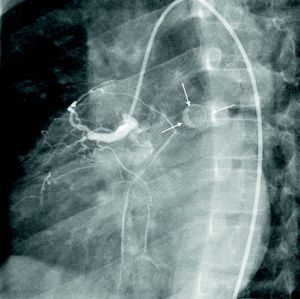

At the age of 11, he was referred to the pediatric cardiology department due to angina and exertional dyspnea of one month's evolution. The chest X-ray revealed a round area of calcification in the upper left portion of the cardiac silhouette (Fig. 1). There were no alterations on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Echocardiography showed ectasia of the left coronary artery of 4 and 5mm in the proximal and distal segments, respectively, with no wall motion abnormalities or mitral regurgitation. During nuclear perfusion scan with exercise, the patient reported chest discomfort at peak exercise, when the ECG showed ST-segment depression in II, III, aVF, V5 and V6. The nuclear perfusion scan during exercise showed severe hypoperfusion in the apex and the anteroseptal, apical-septal, and anteroapical segments and moderate hypoperfusion in the mid and basal segments of the anterior, inferior and inferoseptal walls, corresponding to the territories of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the right coronary artery (RCA), the alterations being reversed at rest. Cardiac catheterization revealed occlusion of the proximal segment of the LAD downstream of the calcified aneurysm, with retrograde filling by collateral circulation from the proximal branches of the left coronary artery (Fig. 2), and of the proximal RCA, with retrograde filling by collateral circulation from the left coronary artery (Fig. 3). Left ventriculography demonstrated good function, with no ventricular aneurysmal alterations.

(A) Left coronary angiography: left anterior descending artery occluded distal to the calcified aneurysm (arrow). (B) Left coronary angiography showing calcified aneurysm (arrows). (C) Left coronary angiography: occluded left anterior descending artery with late retrograde filling by collaterals from the left coronary circulation (arrows).

The patient underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery without cardiopulmonary bypass, using a left internal mammary artery pedicle graft to revascularize the mid third of the LAD and the saphenous vein for the distal RCA. The surgery and postoperative period were uneventful and he was discharged medicated with aspirin at antiplatelet doses and propanolol.

Seven months after the operation, nuclear perfusion scanning with exercise showed no clinically significant ischemia, reflecting a good surgical result. The echocardiogram showed excellent global ventricular function, with no wall motion abnormalities.

To date (one year after surgery), the patient has remained asymptomatic.

DiscussionCoronary artery alterations in KD can appear towards the end of the first week of illness and reach peak incidence and severity by four to six weeks.4

In the acute phase, echocardiography is the method of choice for cardiovascular evaluation and should be performed as soon as the diagnosis is suspected, but treatment with IV immunoglobulin should not be delayed. For uncomplicated cases, if the initial echocardiogram is normal, it should be repeated at two and at six to eight weeks after onset of the disease. In a study by Scott et al., no patient with a normal echocardiogram at between two weeks and two months after disease onset presented abnormalities when assessed one year later. However, even if no coronary enlargement is present, there may be alterations in coronary function or coronary flow reserve, as well as aortic root dilatation, and so many authors recommend repeat echocardiography beyond eight weeks, although this is considered optional in the current AHA guidelines.1 Closer monitoring is required with further diagnostic exams to guide management of children at higher risk (those with persistent fever or who exhibit coronary abnormalities, ventricular dysfunction, pericardial effusion, or valvular regurgitation); these complementary tests may include ECG, 24-hour ECG, exercise testing (ECG or echocardiography), nuclear perfusion scan, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography or cardiac catheterization.1,5

In the present case, IV immunoglobulin therapy was begun late, increasing the risk of coronary complications. Although echocardiographic assessment was performed two weeks after disease onset, this showed no abnormalities, but no further assessments were performed, despite recommendations to the contrary. Presumably the aneurysm developed later, in accordance with the peak of incidence mentioned above, which was not detected because echocardiography was not repeated.

The AHA guidelines establish strategies for treatment and long-term follow-up according to risk stratification for myocardial ischemia. When an aneurysm is detected, antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy should be continued depending on the size of the aneurysm; it is important to maintain regular follow-up with ECG, echocardiography and exercise testing. The recommended frequency of these exams varies according to coronary artery morphology, which determines ischemic risk.1,5 If the aneurysm is diagnosed early, close follow-up and complementary exams are called for. In the long term, in patients with complex lesions on echocardiography, wall motion abnormalities or evidence of ischemia (clinical signs or findings of complementary exams), coronary angiography provides more detailed anatomical information, making it possible to detect coronary stenosis or thrombotic occlusion and to determine the extent of collateral circulation.1

Balloon angioplasty has not been successful when performed more than two years after the acute illness because of dense fibrosis and calcification in the arterial wall.1 Percutaneous coronary intervention is indicated in patients with ischemic symptoms, ischemic alterations on exercise testing or severe stenotic lesions (≥75% stenosis) at risk of progressing to ischemia. It is contraindicated for individuals who have multiple, ostial, or long-segment lesions or left ventricular dysfunction.5

Surgical revascularization may be considered in KD when there is severe occlusion of the left main coronary artery, of the proximal segment of the LAD, or of more than one major coronary artery, and/or when the collateral arteries are in jeopardy.1 In the case presented, two major coronaries were affected with occlusion of the proximal segment of the LAD.

The preferred grafts for coronary artery bypass in these patients are the internal mammary arteries, since these grow with the somatic growth of children,1,6 do not appear to be affected by atherosclerosis, and may have advantages in terms of endothelial function.6

In the present case, the left internal mammary artery was used for the LAD and the saphenous vein for the RCA. Saphenous vein grafts have shown good results in the right coronary circulation,7,8 with excellent long-term outcomes in children with KD.9 Furthermore, in this way the right internal mammary artery can be spared in case reoperation should be necessary in the future.

Kitamura et al.6 reported survival of 95% and an event-free rate of 60% at 25 years of follow-up after coronary artery bypass graft surgery in KD. In any event, regular follow-up should always be maintained, since there is a progressive decline in the event-free rate6 and endothelial function abnormalities persist many years after the acute phase, even in patients without coronary involvement.10

ConclusionThis case report highlights the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of KD, bearing in mind its potential late complications. Patients with coronary alterations must be monitored clinically and by additional diagnostic techniques according to the clinical situation in order to detect ischemia early. When ischemic disease is present, there are precise indications for coronary artery bypass graft surgery and the medium-term results in this patient were excellent.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Santos, V; Cirurgia de revascularização coronária após Doença de Kawasaki. Rev Port Cardiol 2012. doi:10.1016/j.repc.2012.04.002