Scimitar syndrome (SS) is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by partial or complete anomalous pulmonary venous drainage of the right or left lung into the inferior vena cava. The syndrome is commonly associated with hypoplasia of the right lung, pulmonary sequestration, persistent left superior vena cava, and dextroposition of the heart. We report a rare variant of SS in a 44-year-old man together with a single aortic trunk, as well as a coronary-cameral venous fistula.

A síndrome de Cimitarra (SC) é uma malformação congénita rara, caracterizada por uma drenagem pulmonar anómala parcial ou total do pulmão direito ou esquerdo, na veia cava inferior. Esta síndrome é frequentemente associada a hipoplasia do pulmão direito, sequestração pulmonar, persistência de veia cava superior esquerda e dextroposição do coração. Reportamos uma variante rara de SC num homem de 44 anos com tronco supra-aórtico único e fistula coronário-auricular.

Scimitar syndrome (SS) is a rare and complex congenital anomaly, characterized by partial or complete anomalous pulmonary venous drainage from the right or left lung into the inferior vena cava (IVC), though drainage into the hepatic vein, right atrium (RA) or left atrium (LA), or the portal vein can also occur. According to the original definition, the syndrome is commonly associated with hypoplasia of the right lung, pulmonary sequestration, persistent left superior vena cava, and dextroposition of the heart.1,2 In two-thirds of cases, the scimitar vein provides drainage for the entire right lung, but in one third, this vein drains only the lower portion of the right lung.3 Partial abnormalities of pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) are seen in 0.4–0.7% of adult autopsies, while patients with SS account for 3–5% of these cases.4,5 SS constitutes 0.5–1% of all congenital heart defects. This rare anomaly has an incidence of approximately 1-3 per 100000 live births; however, the true incidence may be higher because many patients remain asymptomatic.6 The etiology is not completely understood. In several patients with total anomalous pulmonary venous return, the gene locus has been mapped to chromosome 4q12,7 and females are more frequently affected than males. The scimitar sign refers to the crescent (resembling the Turkish sword) described by the descent of the anomalous pulmonary vein (the tip of the crescent points inferiorly and medially to the diaphragm/right heart border junction). The concavity of the crescent is adjacent to the junction of the diaphragm and right heart border.

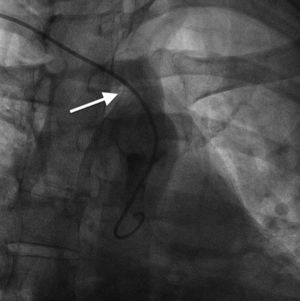

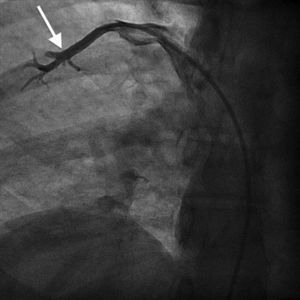

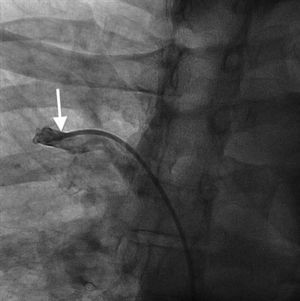

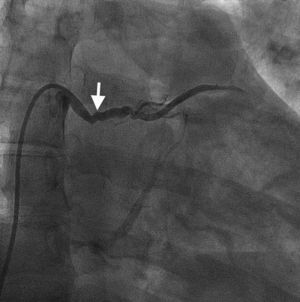

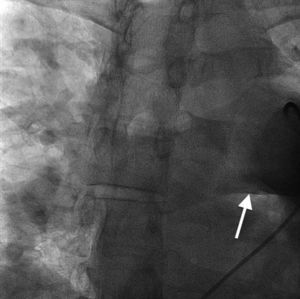

Case reportA 44-year-old man presented with several weeks of palpitations. He also described symptoms of dyspnea with mild exertion and substernal chest discomfort at rest. He had a history of long-standing systemic hypertension. The 12-lead ECG showed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. His 2D Doppler echocardiogram revealed a mildly enlarged RA and right ventricle (RV). He subsequently underwent right and left heart catheterization with selective coronary angiography. Right and left heart catheterization with a full oximetry run to calculate shunts revealed Qp/Qs of 1.3. Selective coronary angiography was performed using right radial artery access, and showed no significant coronary disease. However, angiography of the aortic arch showed a single trunk takeoff for the large vessels from the aortic arch (Figure 1). Using right femoral vein access, a 5-Fr multipurpose diagnostic catheter was advanced into the upper (Figure 2) and middle (Figure 3) right pulmonary veins as they opened into the superior vena cava (SVC). To exclude any possible associated atrial septal defect, an MP-1 catheter was engaged into what proved to be a coronary-cameral fistula (CCF) opening into the RA separately from the coronary sinus (Figure 4), the CCF went from the coronary vein to the RA and the coronary sinus was also filled with contrast retrogradely from the vein (Figure 4). Pulmonary angiography using a 5-Fr pigtail catheter showed a moderately dilated pulmonary trunk (Figure 5). Following consultations with the cardiothoracic surgery and pediatric cardiology teams, it was felt that the best course of management would be to follow the patient clinically with serial echocardiography, as there was no significant right-to-left shunt.

SS is a complex form of PAPVR, which is a connection failure between the right pulmonary veins and the LA during fetal development. Variations in PAPVR include the right pulmonary veins draining into the SVC-LA junction, RA, or IVC, or as in our case, separately to a high SVC. In SS, an anomalous right pulmonary vein generally draining the entire right lung but occasionally the middle and superior lobes, may descend in a cephalad-to-caudal direction toward the diaphragm with a crescent (scimitar) shape. This vein then curves sharply to the left just above or below the IVC-RA junction.8 The anomalous right pulmonary venous trunk usually courses anterior to the hilum of the right lung and connects to the IVC just superior to the orifices of the hepatic veins. Rarely, it drains into the left atrium, with normal venous return.9

In this patient, the right upper and middle pulmonary veins drained into the high SVC and then ultimately into the RA, leading to increased pulmonary circulation as shown by the enlarged right chambers and main pulmonary artery.

The most common aortic arch branching pattern in humans consists of three great vessels originating from the arch of the aorta: the innominate, left common carotid and left subclavian arteries. In “bovine” aortic arch, rather than arising directly from the aortic arch as a separate branch, the left common carotid artery origin is moved to the right and merges with the origin of the innominate artery, or the left common carotid artery originates directly from the innominate artery rather than as a common trunk. A single brachiocephalic trunk originating from the aortic arch and then dividing into right and left brachiocephalic trunks or trifurcating to brachiocephalic, left common carotid and subclavian artery is a very rare anomaly, with few cases reported in the literature,10,11 and there is no previously reported case of SS with this anomaly.

Our patient had a venous CCF draining into the RA from the coronary vein in addition to the right upper and middle pulmonary veins draining through the SVC. There is no previously reported case of SS associated with venous CCF in the literature. Coronary-cameral fistulas are unusual congenital or acquired anomalous communications between an epicardial coronary artery and a cardiac chamber: the RA, coronary sinus, right ventricle, left atrium, or left ventricle. In a review of 304 patients with CCF and coronary vascular fistula (CVF), a continuous cardiac murmur was heard in 82% of the subjects. Dyspnea, chest pain and angina pectoris, palpitations, and fatigue are reported symptoms in clinical presentations. Although rare, infective endocarditis has been reported in patients with CCF, but not in those with CVF.12

Surgical repair of SS consists of redirecting the pulmonary venous drainage into the LA, by either baffling the anomalous drainage into the LA via a tunnel or transecting the “scimitar drainage” near its entrance into the IVC and then reimplanting it directly into the LA.5,6 The surgical option is, however, associated with a relatively high incidence of interruption failure, reinserted pulmonary vein stenosis, surgical complications, and redo procedures. Surgical correction is considered in symptomatic patients or in those with increased pulmonary blood flow and signs of right heart dilation with a significant shunt (Qp/Qs ≥1.5).

In the most common form of SS, there is anomalous right pulmonary vein drainage into the IVC with anomalous systemic arterial supply (ASAS) from the abdominal aorta toward the affected pulmonary parenchyma, leading to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent volume overload and heart failure.

If the presence of a large ASAS to the right lung with pulmonary overcirculation is detected preoperatively (which it was not in our case), occlusion of the ASAS is frequently performed percutaneously to encourage compensatory growth of the remaining normal lung tissue and to reduce both the associated left-to-right shunt and the risk of chronic and recurrent infection in the abnormal lung in later life. Successful percutaneous occlusion of ASAS in infants with SS has emerged as an acceptable treatment using the Amplatzer™ vascular plug device (AGA Medical, Golden Valley, MN).13,14 In a study of 16 infants who underwent percutaneous ASAS interruption, Uthaman et al.13 reported significant reduction in left-to-right shunt and pulmonary artery pressures in >90% of the patients, which translated into symptomatic improvement as well as growth of the right lung in follow-up. Furthermore, this approach leads to sustained long-term clinical improvement without need for further surgical correction in the majority of patients.

In conclusion, in this case report we describe a patient with scimitar syndrome with very unusual associated anomalies of a single aortic trunk and venous CCF.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.