Although half of saphenous vein grafts (SVGs) present obstructive atherosclerotic disease 10 years after implantation, controversy remains concerning the ideal treatment. Our aim was to compare percutaneous revascularization (PCI) options in SVG lesions, according to intervention strategy and type of stent.

MethodsA retrospective single-center analysis selected 618 consecutive patients with previous bypass surgery who underwent PCI between 2003 and 2008. Clinical and angiographic parameters were analyzed according to intervention strategy – PCI in SVG vs. native vessel vs. combined approach – and type of stent implanted – drug-eluting (DES) vs. bare-metal (BMS) vs. both. A Cox regressive analysis of event-free survival was performed with regard to the primary outcomes of death, myocardial infarction (MI) and target vessel failure (TVF).

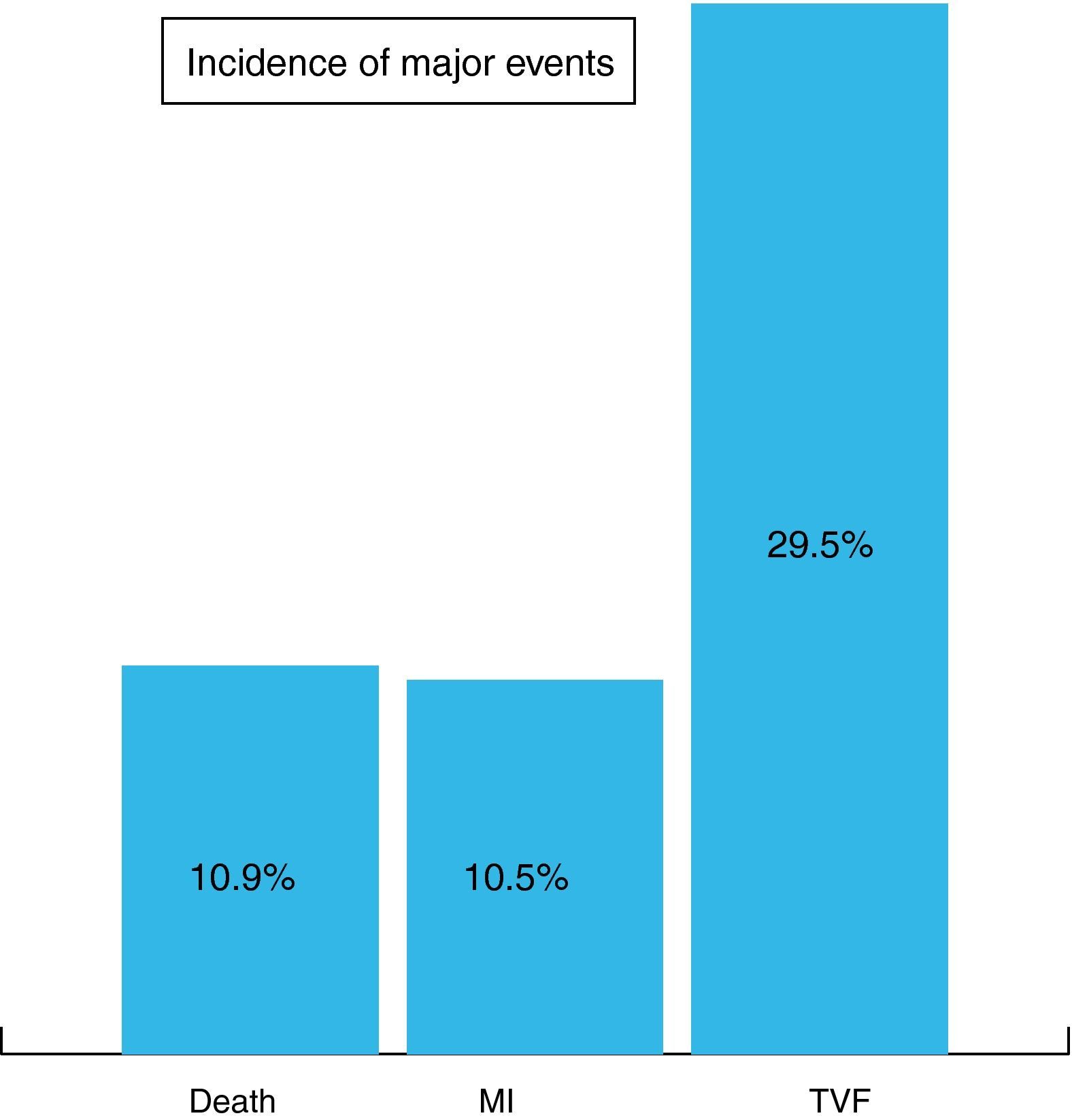

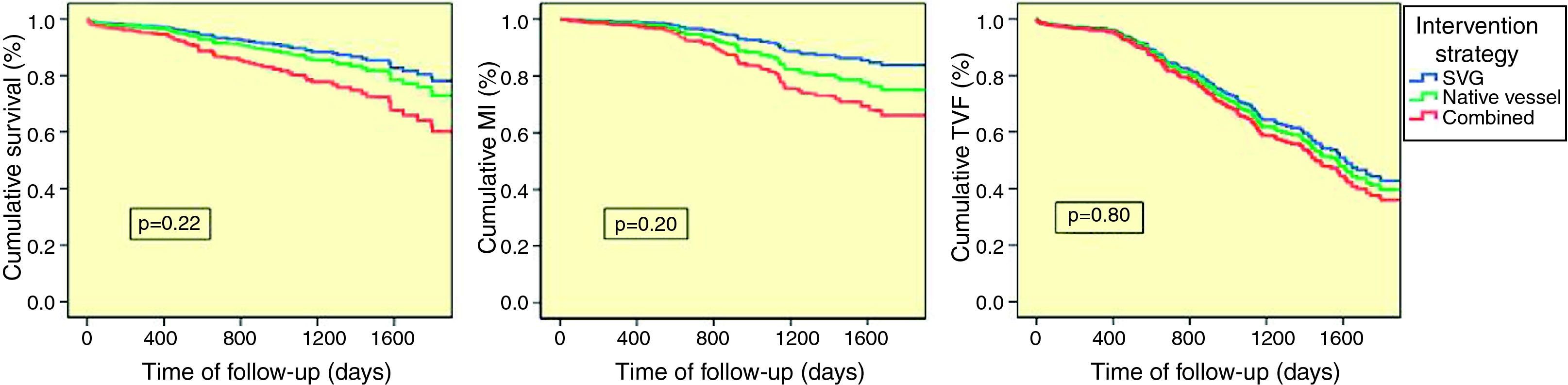

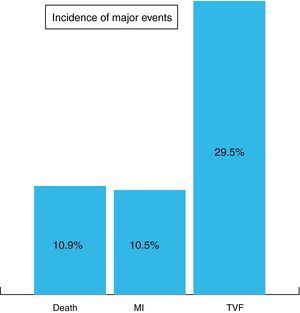

ResultsDuring a mean follow-up of 796±548 days the rates of death, MI and TVF were 10.9%, 10.5% and 29.5%, respectively. With regard to intervention strategy (74.4% of PCI performed in native vessels, 17.2% in SVGs and 8.4% combined), no significant differences were seen between groups (death p=0.22, MI p=0.20, TVF p=0.80). The type of stents implanted (DES 83.2%, BMS 10.2%, both 3.2%) also did not influence long-term prognosis (death p=0.09, MI p=0.11, TVF p=0.64). The implantation of DES had a favorable impact on survival (p<0.001) in the subgroup of patients treated in native vessels but not in SVG.

ConclusionsAmong patients with SVG lesions, long-term mortality, MI and TVF were not affected by intervention options, except for the favorable impact on survival of DES in patients treated in native vessels.

Apesar de metade das pontagens venosas aorto-coronárias apresentarem doença aterosclerótica obstrutiva dez anos após a cirurgia, as estratégias ideais de tratamento permanecem controversas. O nosso objetivo foi comparar diferentes opções de revascularização percutânea em doentes com lesões de pontagens venosas, relativamente à estratégia de intervenção e tipo de stent.

MétodosEstudo retrospetivo de centro único incluindo 618 doentes consecutivos com cirurgia de revascularização coronária prévia, submetidos a PCI entre 2003 e 2008. Avaliação de parâmetros clínicos e angiográficos de acordo com a estratégia de revascularização – PCI da pontagem venosa (SVG), vaso nativo ou abordagem combinada – e tipo de stent implantado – farmacoativo (DES), metálico (BMS) ou ambos. Realizada análise regressiva de Cox quanto a sobrevida livre de eventos para os objetivos primários morte, enfarte do miocárdio (EAM) e falência de vaso alvo (TVF).

ResultadosAo longo de um seguimento médio de 796±548 dias foram registadas 10,9% de mortes, 10,5% de EAM e 29,5% de TVF. Referentemente à estratégia de intervenção (74,4% de PCI realizadas em vaso nativo, 17,2% em SVG e 8,4% combinadas), não se observaram diferenças significativas entre os grupos (morte P = 0,22, EAM P = 0,20, TVF P = 0,80). O tipo de stent utilizado (DES 83,2%, BMS 10,2%, ambos 3,2%) também não influenciou o prognóstico a longo prazo (morte P = 0,09, EAM P = 0,11, TVF P = 0,64). A implantação de DES teve um impacto favorável na sobrevivência (p < 0,001) nos doentes intervencionados no vaso nativo mas não em SVG.

ConclusõesNuma população de doentes com lesões de SVG, a mortalidade, EAM e TVF a longo prazo não foram afetadas pelas opções de intervenção percutânea, com a exceção do impacto favorável na sobrevivência demonstrada pelos DES em doentes tratados nos vasos nativos.

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a highly effective therapy in ischemic heart disease. However, its success is affected by the limited life expectancy of saphenous vein bypass grafts (SVGs), which are still used in almost all interventions.1,2 Most recent studies report an estimated patency rate of 50–60% for SVGs after 10 years, compared to 85–95% for arterial conduits.3 Three main mechanisms are described for vein graft failure. In the early postoperative period (first month), acute thrombosis due to technical and anatomical factors is the dominant etiology. In the subacute period (second to twelfth month) the major role is played by intimal hyperplasia, resulting from the graft's adaptation to higher arterial pressures with consequent loss of endothelial inhibition and smooth muscle cell proliferation. During the late period (after the first year), accelerated atherosclerosis becomes the most important mechanism for graft stenosis and occlusion. Compared to native vessels, vein graft atheromas are more diffuse and concentric and less calcified and have poorly developed or absent fibrous caps, making them especially prone to rupture with consequent thrombotic occlusion of the graft.1,4

Stenosed or occluded SVGs can be treated by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or repeat CABG. Compared to first CABG, repeat CABG is technically more difficult, carries a higher risk of death and provides less symptomatic improvement.2 As a result, PCI is currently the preferred treatment for SVG lesions. However, two major questions concerning percutaneous revascularization of CABG patients remain unanswered. The first is where to intervene: in the venous graft itself or in the native coronary artery. Percutaneous treatment of soft and friable, degenerated vein graft lesions is associated with less favorable immediate results and more adverse in-hospital events, and poses unique procedural challenges due to the frequent presence of thrombi superimposed on critical graft stenosis with a consequent tendency for distal embolization and periprocedural myocardial infarction. In the long term, results are disappointing, with high recurrence rates due to restenosis and emergence of new lesions resulting in target vessel failure (TVF).4–7 Nonetheless, only a few small retrospective studies comparing the two strategies have been published, with inconclusive results, and the general practice is to decide on an individual basis.8,9 The second question concerns the most suitable stent for PCI of SVG lesions. Although superior to balloon angioplasty,10–13 results of stent implantation in SVG lesions are not as good as in native coronary arteries.13 Initial evidence retrospectively comparing bare-metal (BMS) with drug-eluting (DES) stents tended to favor DES, with a lower incidence of major adverse cardiac events mostly due to a reduction in target vessel revascularization (TVR).14–17 However, the recent publication of the only two randomized studies in this area has questioned the superiority of DES. The RRISC (Reduction of Restenosis In Saphenous vein grafts with Cypher stent) trial, comparing sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) with BMS, showed SES to be superior in target lesion and target vessel revascularization at 6 months, with similar mortality and myocardial infarction (MI) rates.18 However, the DELAYED RRISC (Death and Events at Long-term follow-up AnalYsis: Extended Duration of the Reduction of Restenosis In Saphenous vein grafts with Cypher stent) trial showed loss of repeated revascularization benefits and significantly higher mortality in SES compared with BMS at 32 months.19 The SOS (Stenting Of Saphenous vein grafts) trial, comparing paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES) with BMS, also showed disappointing results, with less TVR and TVF in the PES group but similar MI and mortality rates at a mean follow-up of 1.5 years.20 This lack of consistent long-term benefit of DES over BMS in this context21–24 led to the recent publication of two meta-analyses, also with controversial results: one, including 19 studies with 3420 patients, reported a benefit for DES vs. BMS only in TVR and MI25; the second, including 22 studies and 5543 patients, showed significantly better results for DES in TVR, TLR and total and cardiovascular mortality.26 Although revitalized, this question seems far from settled.

The aim of our study was to compare long-term angiographic and clinical outcomes of different percutaneous revascularization options in patients with SVG lesions, with regard to intervention strategy – PCI in SVG or native coronary artery – and type of stent to implant – BMS or DES.

MethodsPatients and proceduresA retrospective analysis of the ACROSS (Angioplasty and Coronary Revascularization On Santa Cruz hospital) Registry, a single-center dedicated interventional cardiology database developed in our Intervention Unit comprising 5611 angioplasties performed consecutively between January 2003 and June 2008, identified 618 patients with previous CABG who underwent PCI, in a total of 793 procedures. All patients were selected for treatment on the basis of spontaneous angina or inducible ischemia documented by noninvasive testing. Selection of interventional strategy and type of stent was left to the operator's discretion and evolved during the study. All patients were treated with antithrombotic and/or anticoagulant therapy as indicated.

Data collection and follow-upDemographic characteristics, cardiac risk factors, clinical presentation, angiographic and procedural results and in-hospital outcomes were prospectively recorded in the above-described database. Clinical follow-up was obtained in 96% of patients, by telephone interviews with the patient or family and review of medical records. A mean follow-up of 796±548 days (interquartile range 436–1117 days) was achieved.

Study objectives and definitionsThe primary outcome of this retrospective analysis was all-cause mortality. Additional outcomes were the rate of major adverse cardiac events: MI, defined as typical rise and fall of troponin or CK-MB above the upper limit of normal, with either ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic changes indicative of ischemia (ST-segment elevation or depression or development of pathologic Q waves); and TVF, a composite of cardiac death (death related to target vessel or cardiac death not clearly attributed to another vessel), target vessel-related MI (ST-segment elevation or non ST-segment elevation MI attributed to the target vessel or not attributable to another vessel) and repeated TVR, by means of CABG or PCI. All deaths were considered cardiac unless an unequivocal noncardiac cause was established.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® 17.0 (2008). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and continuous variables as mean±standard deviation. Comparative evaluation of clinical and angiographic parameters was performed using one-way ANOVA. The covariates were: (1) clinical characteristics – age, gender, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, smoking, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, peripheral arterial disease, previous acute myocardial infarction, previous stroke, left ventricular ejection fraction, presentation as acute coronary syndrome and hemodynamic instability; (2) angiographic characteristics – number of affected coronary arteries, number of affected coronary segments and number of coronary lesions (defined by ≥50% stenosis); (3) procedural characteristics – need for urgent PCI (primary PCI or PCI within the first 72h of an acute coronary syndrome), use of Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors, number of treated vessels, number of treated lesions, number of stents, total stent length, minimum stent diameter, angiographic success and achievement of complete revascularization. Survival curves for the pre-determined study outcomes were constructed for the mean follow-up time using multivariate Cox regressive analysis adjusted for significant covariates. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

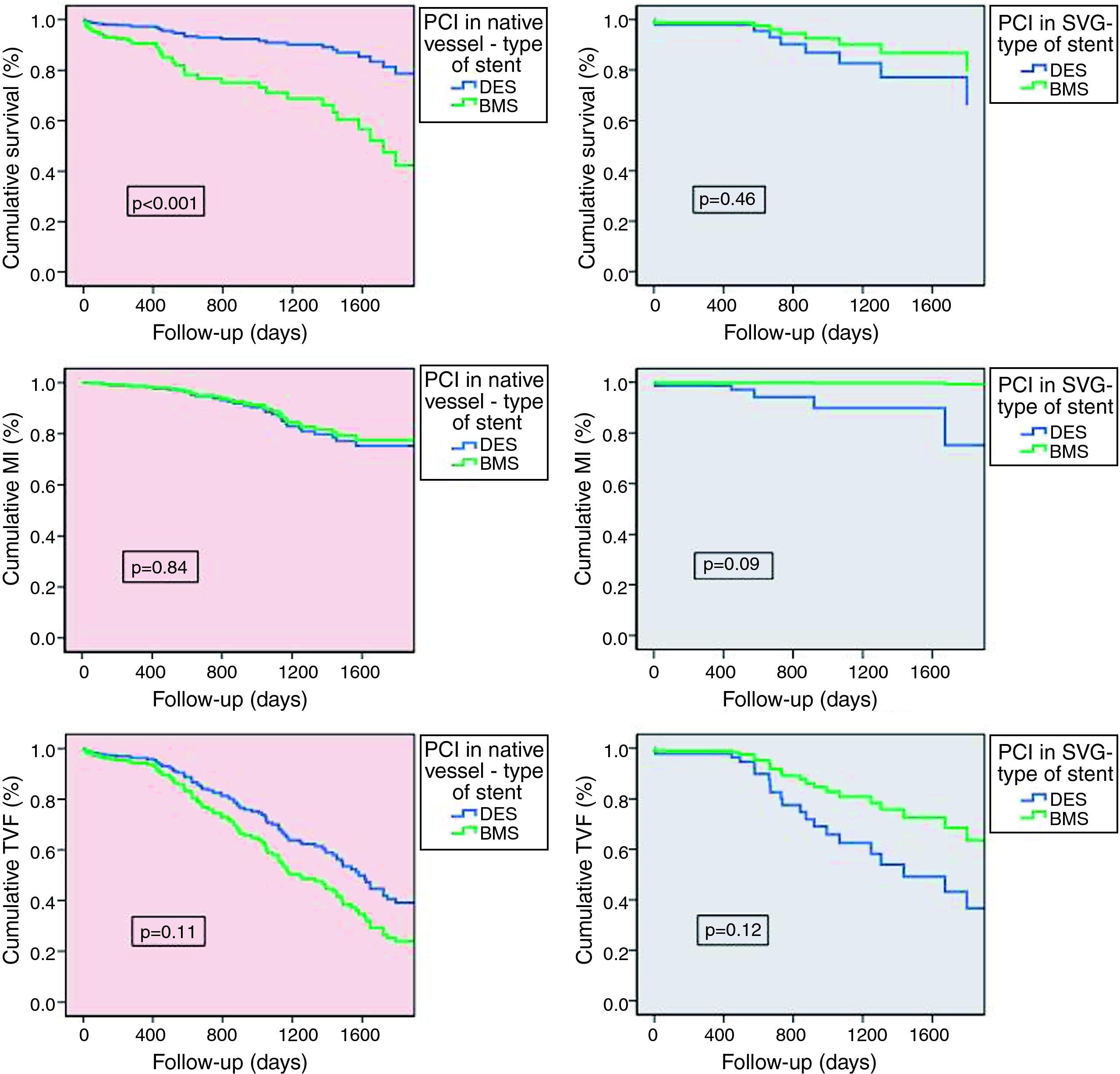

ResultsBaseline characteristics and overall outcomesThe study population included 618 patients with a mean age of 66.7±9.5 years, 73% male. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Mean age of degenerated SVGs was 10.2±2.3 years.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |

| Mean age (years) | 66.7±9.5 |

| Male | 72.3% |

| Hypertension | 72.5% |

| Diabetes | 33.2% |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 69.9% |

| Smoking | 8.8% |

| LVEF <50% | 26.0% |

| Previous MI | 49.6% |

| Form of presentation | |

| STEMI | 3.4% |

| NSTEMI | 22.6% |

| UA | 11.0% |

| Stable/asymptomatic CAD | 63.1% |

| SVG age (years) | 10.1±2.3 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non ST-segment myocardial infarction; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SVG: saphenous vein graft; UA: unstable angina.

At completion of a mean follow-up of 27±18 months, the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was 10.9% death, 10.5% MI and 29.5% TVF (Figure 1).

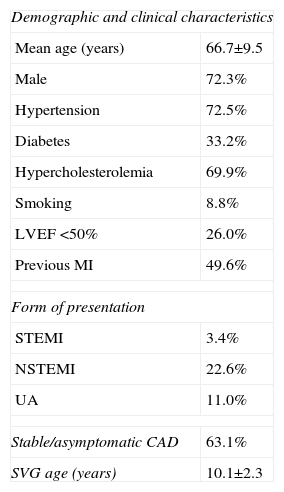

Intervention strategyOf the study population, 74.4% were treated in the native coronary artery, 17.2% in the SVG and 8.4% in both territories. Baseline comparison between groups showed no significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. Angiographically, the only significant differences between patients treated in SVGs and in native vessels were greater minimal stent diameter in the first group and greater use of Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors in the second. Patients revascularized in both territories presented more severe coronary disease and underwent more complex PCI procedures, based on the higher number of treated lesions and vessels as well as number of stents implanted (Table 2).

Comparison of baseline and procedural characteristics according to intervention strategy.

| PCI strategy | Saphenous graft (n=123) | Native vessel (n=533) | Combined (n=60) | pa |

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (years) | 67.0±9.4 | 66.5±9.6 | 67.7±9.0 | 0.62 |

| Male | 85% | 76% | 85% | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 67% | 73% | 80% | 0.19 |

| Diabetes | 57% | 63% | 48% | 0.43 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 70% | 71% | 67% | 0.82 |

| Smoking | 11% | 8% | 10% | 0.43 |

| Chronic renal failure | 2% | 3% | 3% | 0.68 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 17% | 16% | 15% | 0.93 |

| Previous MI | 46% | 48% | 53% | 0.61 |

| Previous stroke | 7% | 8% | 12% | 0.58 |

| LVEF <50% | 31% | 23% | 26% | 0.31 |

| Presentation as ACS | 43% | 32% | 48% | 0.007 |

| Need for hemodynamic support | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0.60 |

| Time from CABG (years) | 10.2±2.2 | 10.2±2.3 | 9.5±2.4 | 0.52 |

| Angiographic characteristics | ||||

| Number of affected vessels | 2.6±0.6 | 2.7±0.6 | 2.8±0.4 | 0.07 |

| Number of affected segments | 4.6±1.4 | 4.7±1.8 | 5.4±1.6 | 0.006 |

| Number of lesions | 5.2±1.8 | 5.1±2.1 | 6.8±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Urgent PCI | 22% | 18% | 20% | 0.65 |

| Gp IIb/IIIa | 25% | 16% | 25% | 0.03 |

| No. of treated vessels | 1.0±0.5 | 1.3±0.6 | 1.8±0.6 | <0.001 |

| No. of treated lesions | 1.0±0.4 | 1.6±0.9 | 2.3±0.8 | <0.001 |

| No. of stents | 1.5±0.8 | 1.7±1.0 | 2.7±1.2 | <0.001 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 29.6±18.1 | 31.3±19.4 | 51.6±23.1 | <0.001 |

| Minimal stent diameter (mm) | 2.9±0.7 | 2.4±0.6 | 2.5±0.6 | <0.001 |

| Angiographic success | 99% | 98% | 100% | 0.47 |

| Complete revascularization | 11% | 14% | 20% | 0.28 |

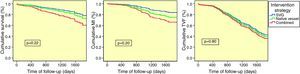

Analysis of 27-month mean follow-up outcomes showed no significant differences between groups for the predetermined outcomes. In the subgroup who underwent combined revascularization, mortality (SVG 8.0% vs. native vessel 10.0% vs. combined 20.0%, p=0.22) and MI (SVG 6.0% vs. native vessel 9.0% vs. combined 20.0%, p=0.20) were non-significantly higher; TVF was similar (SVG 25.0% vs. native vessel 26.0% vs. combined 40.0%, p=0.80) (Figure 2).

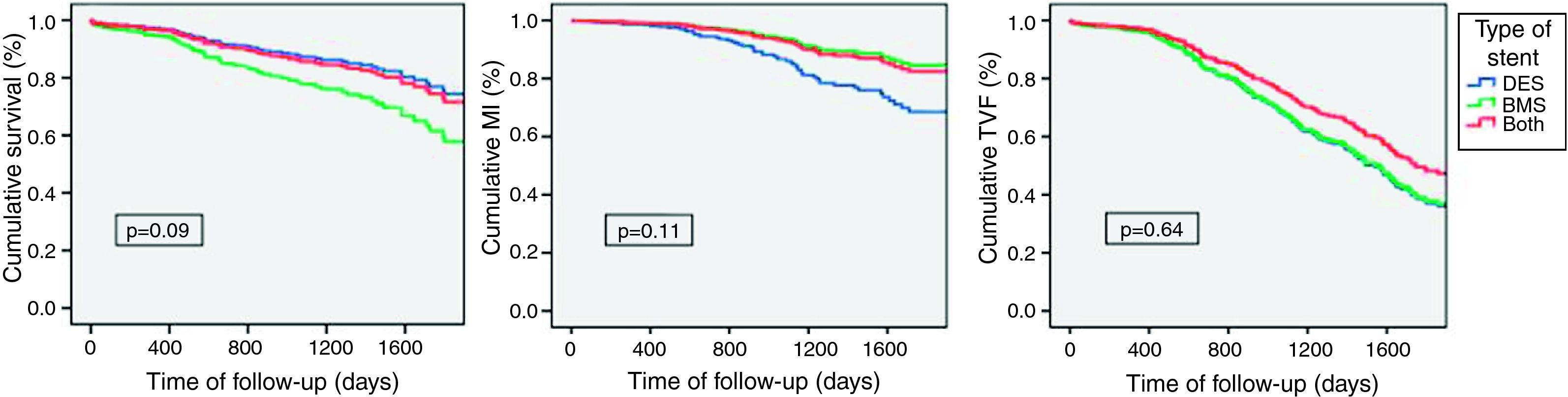

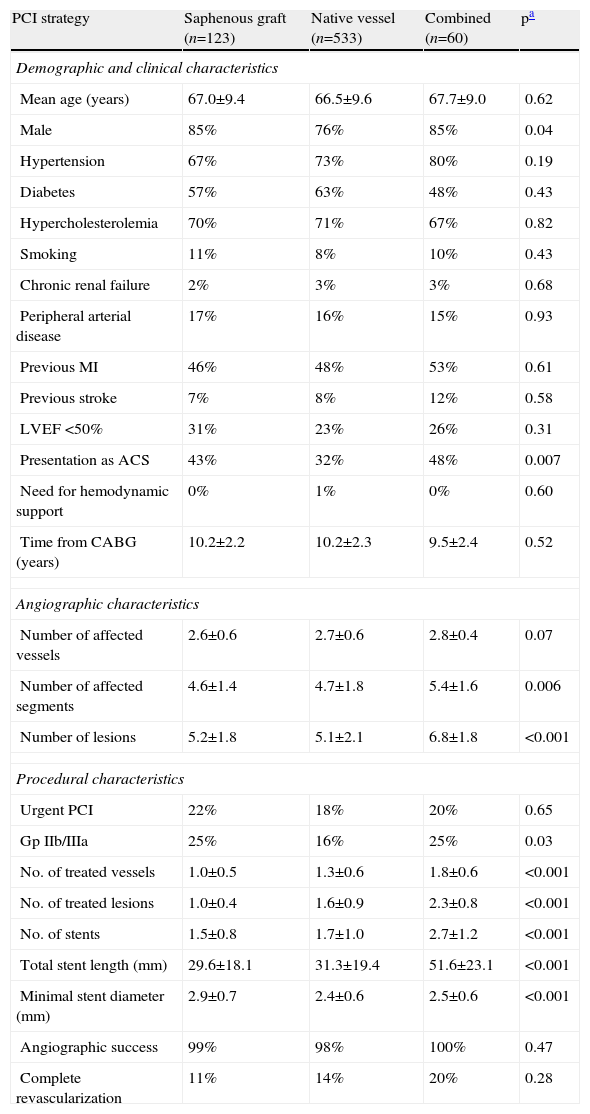

Type of stentThe distribution of stent type was uneven, with 83.2% of the patients undergoing PCI with DES, 10.2% with BMS and 3.2% with both types of stent. Baseline comparison of groups revealed older age and lower incidence of previous MI in the BMS subgroup and less smoking in the DES subgroup. With regard to angiographic and procedural characteristics, patients treated with both type of stents presented more severe coronary disease and required more complex intervention in terms of number of lesions and vessels treated and number and length of stents implanted. Between patients treated with only one type of stent, the only difference was the larger stent diameter in the BMS subgroup (Table 3).

Comparison of baseline and procedural characteristics according to type of stent implanted.

| Implanted stent | Drug-eluting (n=580) | Bare-metal (n=89) | Both (n=28) | pa |

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (years) | 66.9±9.4 | 69.6±10.0 | 64.4±8.4 | 0.01 |

| Male | 78% | 87% | 86% | 0.10 |

| Hypertension | 74% | 74% | 79% | 0.85 |

| Diabetes | 64% | 61% | 43% | 0.45 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 71% | 70% | 64% | 0.73 |

| Smoking | 7% | 12% | 18% | 0.04 |

| Chronic renal failure | 3% | 3% | 0% | 0.63 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 18% | 12% | 14% | 0.36 |

| Previous MI | 50% | 37% | 61% | 0.04 |

| Previous stroke | 7% | 11% | 4% | 0.32 |

| LVEF <50% | 26% | 22% | 44% | 0.23 |

| Presentation as ACS | 36% | 46% | 32% | 0.16 |

| Need for hemodynamic support | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0.03 |

| Time from CABG (years) | 10.2±2.1 | 10.1±2.4 | 10.4±0.1 | 0.97 |

| Angiographic characteristics | ||||

| Number of affected vessels | 2.7±0.6 | 2.7±0.6 | 2.9±0.4 | 0.34 |

| Number of affected segments | 4.7±1.7 | 4.6±1.7 | 6.0±1.7 | 0.001 |

| Number of lesions | 5.2±2.0 | 5.3±2.2 | 6.9±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Urgent PCI | 19% | 24% | 14% | 0.51 |

| Gp IIb/IIIa | 20% | 16% | 43% | 0.007 |

| No. of treated vessels | 1.3±0.6 | 1.1±0.5 | 1.9±0.4 | <0.001 |

| No. of treated lesions | 1.6±0.9 | 1.3±0.7 | 2.4±0.9 | <0.001 |

| No. of stents | 1.7±1.0 | 1.5±0.7 | 2.9±0.8 | <0.001 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 32.8±20.5 | 25.6±14.7 | 50.0±18.5 | <0.001 |

| Minimal stent diameter (mm) | 2.4±0.6 | 3.1±0.8 | 2.4±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Angiographic success | 99% | 98% | 99% | 0.72 |

| Complete revascularization | 13% | 11% | 25% | 0.16 |

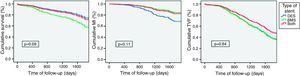

Long-term outcome analysis also showed no significant differences between groups for the defined study outcomes. However, a tendency was seen for higher mortality (DES 10.0% vs. BMS 19.0% vs. both 15.0%, p=0.09) and, conversely, lower MI (DES 12.0% vs. BMS 6.0% vs. both 11.0%, p=0.11) with BMS. The incidence of TVF was similar between groups (DES 29.0% vs. BMS 30.0% vs. both 26.0%, p=0.64) (Figure 3).

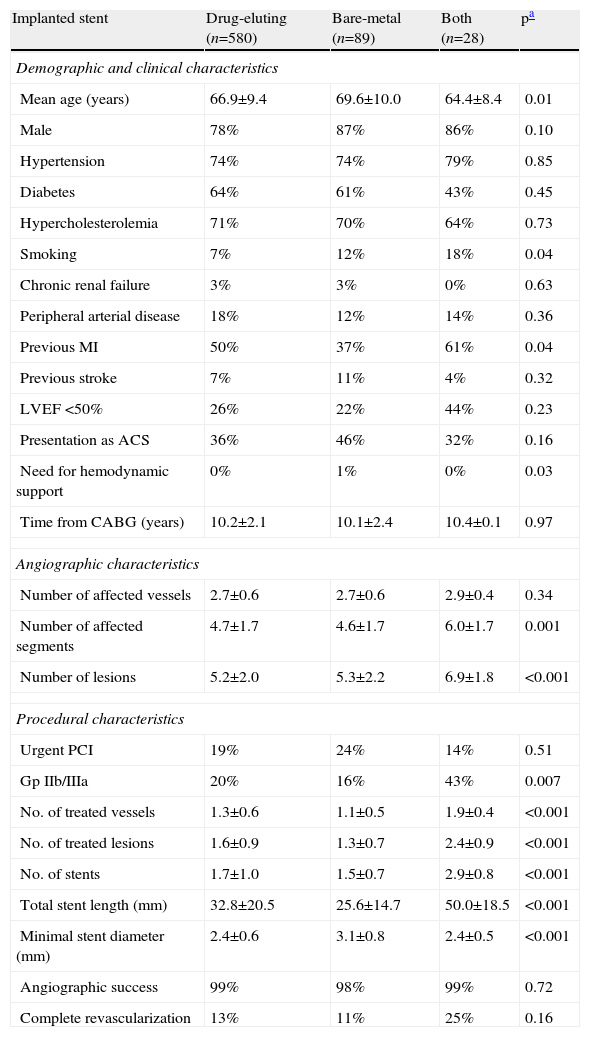

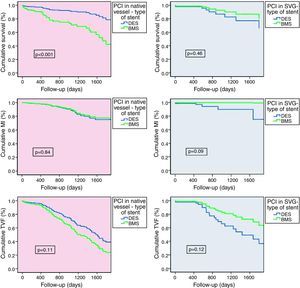

Stent performance according to intervention strategyTo clarify the outcomes, we performed a comparative subanalysis of type of stent implanted for each intervention strategy (Figure 4). In patients treated exclusively in native coronary arteries, 12.0% were implanted with BMS and 82.0% with DES. Long-term outcome analysis showed significantly better survival in patients treated with DES (DES 7.0% vs. BMS 24.0%, p<0.001), with progressive differences over time. These stents also demonstrated a tendency for lower TVF (DES 25.0% vs. BMS 31.0%, p=0.11), MI being similar between the groups (DES 10.0% vs. BMS 7.0%, p=0.84). In patients treated exclusively in SVGs (21.4% of BMS and 78.6% of DES) there were no differences regarding the use of DES or BMS. Nevertheless, BMS showed a tendency for lower MI (DES 7.0% vs. BMS 0%, p=0.09) and TVF (DES 32.0% vs. BMS 21.0%, p=0.12), with similar mortality (DES 11.0% vs. BMS 9.0%, p=0.46).

Comparative outcome subanalysis for type of stent implanted according to intervention strategy, for the predefined outcomes of death (a), myocardial infarction (b) and target vessel failure (c). Statistical test: Cox regression analysis. BMS: bare-metal stent; DES: drug-eluting stent; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SVG: saphenous vein graft; TVF: target vessel failure.

Coronary artery bypass surgery remains the most effective treatment for complex multivessel disease, but its long-term results are affected by the short life expectancy of SVGs.1,2 Nearly half of SVGs are occluded 10 years after implantation,3 making percutaneous revascularization of CABG patients a frequent procedure that represents 10–15% of interventions in most catheterization labs.27 Our study was aimed to clarify different therapeutic options regarding PCI of SVGs only, vs. PCI of native vessels only or a combined approach.

Concerning the intervention strategy and the question of where to intervene, in our study there were no differences in mortality, MI or TVF between patients revascularized in the saphenous graft, in the native coronary artery or in both territories. These results are in agreement with other published studies.8 Angioplasty of the SVG instead of the native vessel is feasible and safe and should be considered a valid option in selected cases, despite the expected higher difficulty of interventional maneuvers inside a vein graft and the higher risk of complications such as vein wall perforation and dislodgment and distal embolization of atherosclerotic and thrombotic material. The key element must be careful and individualized patient selection for each strategy, guided by angiographic indications of ischemia. In our population, operator-based decisions led preferentially to native vessel PCI (74.4%) rather than other strategies. This decision appeared not to be influenced by the patient's clinical status, since baseline characteristics were similar in the two subgroups (Table 2). Combined revascularization in both SVG and native vessel proved to be a good option in complex cases, with similar results despite the presence of more serious coronary disease and more extensive intervention.

Regarding the second issue, the most suitable type of stent, although PCI of coronary lesions with DES has been shown to be superior in several clinical scenarios, the pivotal trials which established the anti-restenotic effect of DES specifically excluded patients with vein graft disease due to its distinct and mostly unknown physiological environment.28 Studies on the effectiveness of DES in SVG disease are limited in number, population size, duration of follow-up, and, with only two exceptions – the RRISC and SOS trials, respectively with sirolimus and paclitaxel-eluting stents – are all retrospective. Most importantly, published results are conflicting, target vessel revascularization being the only endpoint for which DES consistently showed better results than BMS in SVG,5,26 and even this is unsure in the long term, as seen in the DELAYED-RRISC trial.19

Our analysis showed different results in PCI performed in native vessels and in SVGs. In native coronary arteries DES showed significantly lower mortality (p<0.001) and a tendency for lower TVF at 27-month mean follow-up. These results underline the well-documented impact of antiproliferative agents in the prevention of stent restenosis, with consequent benefits in mortality and morbidity. However, our data suggest that in the setting of SVG angioplasty DES do not offer a significant clinical advantage over BMS. In SVG interventions BMS show similar long-term performance with regard to mortality and a tendency for better results in MI and TVF. These results mirror the findings of other published comparison data with long-term follow-up. Possible reasons for the non-inferiority of BMS in this setting are the slightly larger diameters of implanted BMS, the highly thrombotic milieu of saphenous grafts, with potential for a more pronounced inflammatory and thrombotic reaction after DES deployment, and the progressive nature of SVG disease, with a large proportion of events attributable to progression of disease in untreated segments rather than to restenosis.29 The need for long-term follow-up has become more evident in view of the recent results of the DELAYED RRISC trial, which reported a trend for more repeated revascularization procedures in the DES group after the first 6 months, probably reflecting a “late catch-up” phenomenon resulting in more frequent late and very late thrombosis and late restenosis than in native coronary arteries.19 The use of BMS in SVG PCI may therefore be preferable in this cohort of patients.

Study limitationsWe acknowledge several limitations to this study. First, the analysis was not pre-specified, and concerns a nonrandomized single-center population. Treatment selection was entirely at the discretion of each operator. Second, the long time frame for the inclusion criteria of this study group (five and a half years) may lead to confounding effects due to evolution of techniques and equipment. Third, the study is underpowered to detect significant differences in adverse events that occur infrequently, particularly in the exclusively SVG PCI subgroup. Finally, the outcome of patients with SVG disease is dependent on many variables (such as graft plaque volume, degree of graft degeneration and treatment techniques) that could not be accounted for in this retrospective analysis. A prospective, randomized study with angiographic follow-up is necessary to control for confounders. Despite these limitations, this study provides information collected in a large patient population, and reflects the actual clinical presentation and outcomes of SVG disease treatment in routine, daily practice.

ConclusionsIn patients with saphenous graft disease there were no significant long-term follow-up differences between intervention in SVGs and in native vessels. The choice between drug-eluting and bare-metal stents is related to intervention strategy: while in native vessel angioplasty DES should remain the first choice due to their survival advantage, in SVG intervention the use of BMS was not inferior.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.