First introduced in 1960s in response to the extremely high mortality in acute coronary syndromes, Coronary Intensive coronary care units (CCUs) were the first intensive care units dedicated specifically to cardiovascular disease.1 Over the years up to the present, they have undergone a fantastic journey from close electrocardiographic monitoring and prompt defibrillation of malignant ventricular arrhythmias to full extracorporeal life support. It is nonetheless important looking to look back to the foundations: these units remain the best place to monitor and treat critically ill cardiovascular patients, not only because of the availability of sophisticated end-organ support technology, but also because they can call on a highly trained staff of nurses and physicians, as well as specific care bundles and protocols.2

Advances in the therapeutic armamentarium, from optimal medical treatment to increasingly complex percutaneous coronary and structural intervention, have brought us to the point where we stand today: ever greater patient age, complexity and level of comorbidities. This has profound impact on human and technical resources required in CICUs, as well as on patient's length and prognosis.3 Interestingly, some studies on temporal trends in CCUs show a decrease in in-hospital mortality when adjusted for clinical severity.4

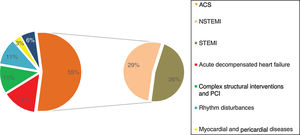

There have been important epidemiologic changes along this way, from predominantly of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), to a much wider variety of cardiovascular conditions. It is estimated that less than half of patient admissions are nowadays due to ACS, with a shift toward fewer cases of ST-elevation ACS, and more of non-ST-elevation ACS.2–5 Other cardiovascular conditions frequently encountered include acute decompensated heart failure, valvular heart disease, rhythm disturbances, myocardial and pericardial disease, complex congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary thromboembolism, as well as iatrogenic complications of complex coronary and structural heart interventions.

Altogether, this led to a change in terminology, from coronary care units to intensive cardiovascular care units (ICCUs), also known as cardiac intensive care units (CICUs).

The first CICU in Portugal was founded in 1969 in Lisbon by Arsénio Cordeiro, and the concept spread as fast as country's financial and bureaucratic constraints allowed, up to the point by the late 1990s when every tertiary hospital had its own CCU. Different levels of care are found in these units, and there is great variation according to geographic region.

The classification proposed by the European Society of Cardiology's Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA) for levels of care in the ICCU is summarized in Table 1.2 There are currently eighteen ICCUs in Portugal, of which eight are Level III units.6 There are virtually no epidemiological and clinical data available on this type of unit in Portugal. Here we present a picture of a contemporary Portuguese level III ICCU, with a total capacity of eight beds, over a period of three consecutive years, 2014 to 2016 (Figure 1).

Levels of intensive cardiovascular care units, by technical capacities and expertise required (adapted from Bonnefoy-Cudraz E. et al., 2017).

| LEVEL I ICCUBasic cardiovascular intensive care | LEVEL II ICCUAdvanced cardiovascular intensive care | LEVEL III ICCUCardiovascular critical care |

|---|---|---|

| • All non-invasive clinical parameters monitoring• 24/7 Echocardiography and thoracic ultrasound• Direct current cardioversion• Non-invasive ventilation• Transcutaneous temporary pacing• Chest tubes• Nutrition support• Physiotherapy in ward | As in level I ICCU plus• Ultrasound-guided central venous line insertion• Pericardiocentesis• Transvenous temporary pacing• Transoesophageal echocardiography• Pulmonary artery catheter/right heart catheterization• Percutaneous circulatory support (IABP, percutaneous axial pump)• Targeted temperature management | As in level II ICCU plus• Extracorporeal life support• Mechanical circulatory support (LVAD, Bi-VAD)• Renal replacement therapy• Mechanical ventilation |

Bi-VAD: biventricular assist device; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; ICCU: intensive cardiovascular care unit; LVAD: left ventricular assist device.

Main diagnoses at admission to a Portuguese level III intensive cardiovascular care unit. Data are from 2014-2016. The total number of patients was 2641, and percentages of this value are presented. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ICCU: intensive cardiovascular care unit; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Patients were predominantly male (68%), with a mean age of 67.1±14.2 years, 21% of patients were aged 80 years. Acute decompensated heart failure patients now represent one sixth of the total, and frequently need advanced therapeutic and monitoring strategies, longer ICCU stay (2.4±1.9 vs. 3.4±3.3 days; p=0.01), and higher rehospitalization rates at 30 days (representing almost 90% of all readmissions, with a global readmission rate of 2%). Overall in-hospital mortality was 3.1% in the studied time period.

Contemporary ICCU admissions are often complicated by non-cardiovascular illnesses, the most frequent being acute respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, and sepsis.3 End-organ support is frequently needed, and familiarity of staff with a range of modalities from mechanical ventilation to extracorporeal life support is key to achieving the best possible clinical outcomes. Table 2 presents statistical data on this subject, based on our recent experience over three years.

End-organ support and invasive procedures in the intensive cardiovascular care unit in three consecutive years.

| Number of patients | Percentage of the total | |

|---|---|---|

| Circulatory support | 71 | 2.7% |

| Inotropic/vasopressor support | 62 | 2.3% |

| IABP | 57 | 2.2% |

| Short-term LVAD | 5 | 0.2% |

| VA ECMO | 18 | 0.7% |

| Temporary transvenous pacemaker | 147 | 5.6% |

| Pericardiocentesis | 28 | 1.1% |

| Severe respiratory dysfunction | 167 | 6.3% |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 115 | 4.4% |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 17 | 0.6% |

| AKI requiring RRT | 16 | 0.6% |

AKI: acute kidney injury; VA ECMO: veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LVAD: left ventricular assist device; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

The greater prevalence of non-cardiovascular diagnosis and related end-organ dysfunctions, together with the patient's increasing age and broader spectrum of interventions performed, poses unique challenges. Cardiologists in ICCUs are now faced with a highly specific subset of critically ill patients, and yet with the need of an integrated intensive-care approach. Although the need for dedicated general intensivists in Level III unit teams is widely recognized, there is general consensus among cardiology societies and working groups that a cardiac intensivist should be the team leader in these units.1,2

A multitude of subspecialization programs for intensive cardiovascular care have been proposed, none of them with good implementation rates. The added difficulties caused by regional and national differences are bringing the implementation of standardized specialization programs to a halt. There is no national certifications available for acute cardiac care in Portugal at the present time, whether for physicians, allied professionals, or training centers.7 However, the Portuguese Society of Cardiology recommends ACCA certification. In 2014, the ACCA published a core curriculum that set out optimal training standards for critical care cardiologists (available for those who achieved competency in general cardiology), comprising a minimum of 12 months of additional training in the ICCU.8 An alternative pathway consists in completing a two-year subspecialization program in intensive care medicine. Another significant challenge over the next few years may be appropriate patient selection for the myriad of techniques and devices available. This is in line with the need to develop research programs, in order to provide evidence on which to base the selection criteria for certain end-organ support modalities and advanced heart failure interventions.9 The concept of the heart team, which was first arose in the area of structural heart interventions, has a long road ahead in this mission. The routine integration of cardiac intensivists in these teams is not only intuitive; it is crucial.

In the end of the day it is as important both to prolong patient's lives and increase quality of life and to avoid suffering and futility. The bar is now settled high in what we can offer to our patients, but we still have to allow Hippocratic and other essential ethical principles to guide us in the most difficult scenarios. A wide-ranging discussion on palliative and end-of-life care in ICCUs is now taking place, and teams should be familiarized with such protocols.10

In conclusion, recent decades have seen spectacular developments in this most fascinating field in cardiology, but current challenges appear to be poised to surpass those that have been overcome. Contemporary Level III ICCUs must have dedicated and highly specialized staff, and serious commitment with clinical investigation in order to further improve patient outcomes. This commitment starts with scrupulous epidemiologic and clinical data reporting, and the use of self-evaluation metrics, both of which have been hereby attempted by the authors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.