Global warming is a result of the increased emission of greenhouse gases. The consequences of this climate change threaten society, biodiversity, food and resource availability. The consequences include an increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) disease and cardiovascular mortality.

In this position paper, we summarize the data from the main studies that assess the risks of a temperature increase or heat waves in CV events (CV mortality, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, and CV hospitalizations), as well as the data concerning air pollution as an enhancer of temperature-related CV risks. The data currently support global warming/heat waves (extreme temperatures) as cardiovascular threats. Achieving neutrality in emissions to prevent global warming is essential and it is likely to have an effect in the global health, including the cardiovascular health. Simultaneously, urgent steps are required to adapt the society and individuals to this new climatic context that is potentially harmful for cardiovascular health. Multidisciplinary teams should plan and intervene healthcare related to temperature changes and heat waves and advocate for a change in environmental health policy.

O aquecimento global é uma das consequências do aumento da emissão de gases com efeito de estufa. Essa consequência das alterações climáticas é uma ameaça à sociedade, à biodiversidade e à disponibilidade de recursos e alimentos. As consequências para a saúde do aquecimento global incluem o aumento do risco de doenças cardiovasculares (CV) e da mortalidade cardiovascular.

Neste position paper resumimos os dados dos principais estudos que avaliam o risco do aumento de temperatura ou a exposição a ondas de calor nos eventos CV (mortalidade CV, enfarte do miocárdio, insuficiência cardíaca, acidente vascular cerebral e hospitalizações CV), assim como os dados relativos à poluição do ar como um potenciador dos riscos de eventos CV relacionados com o aumento da temperatura. Os dados atualmente disponíveis confirmam que o aquecimento global e as ondas de calor (temperaturas extremas) são ameaças cardiovasculares. Nesse contexto, a neutralidade nas emissões deve ser um objectivo prioritário, de modo a reduzir o aquecimento global e, desse modo, reduzir o seu impacto na saúde global, inclusive a saúde cardiovascular. Simultaneamente, deverão ser empregues medidas urgentes de adaptação setorial ao novo contexto climático, potencialmente mais nefasto para a saúde cardiovascular. Equipes multidisciplinares devem planear e intervir nos cuidados de saúde relacionados com o calor e discutir as políticas de saúde relacionadas com o ambiente.

Climate change refers to a shift in seasonal temperatures, rainfall, drought, and wind patterns and is often associated with disasters such as hurricanes, wildfires and floods. Global warming is one of the most prominent features of recent climate change and the 2010–2019 decade was the warmest on record.

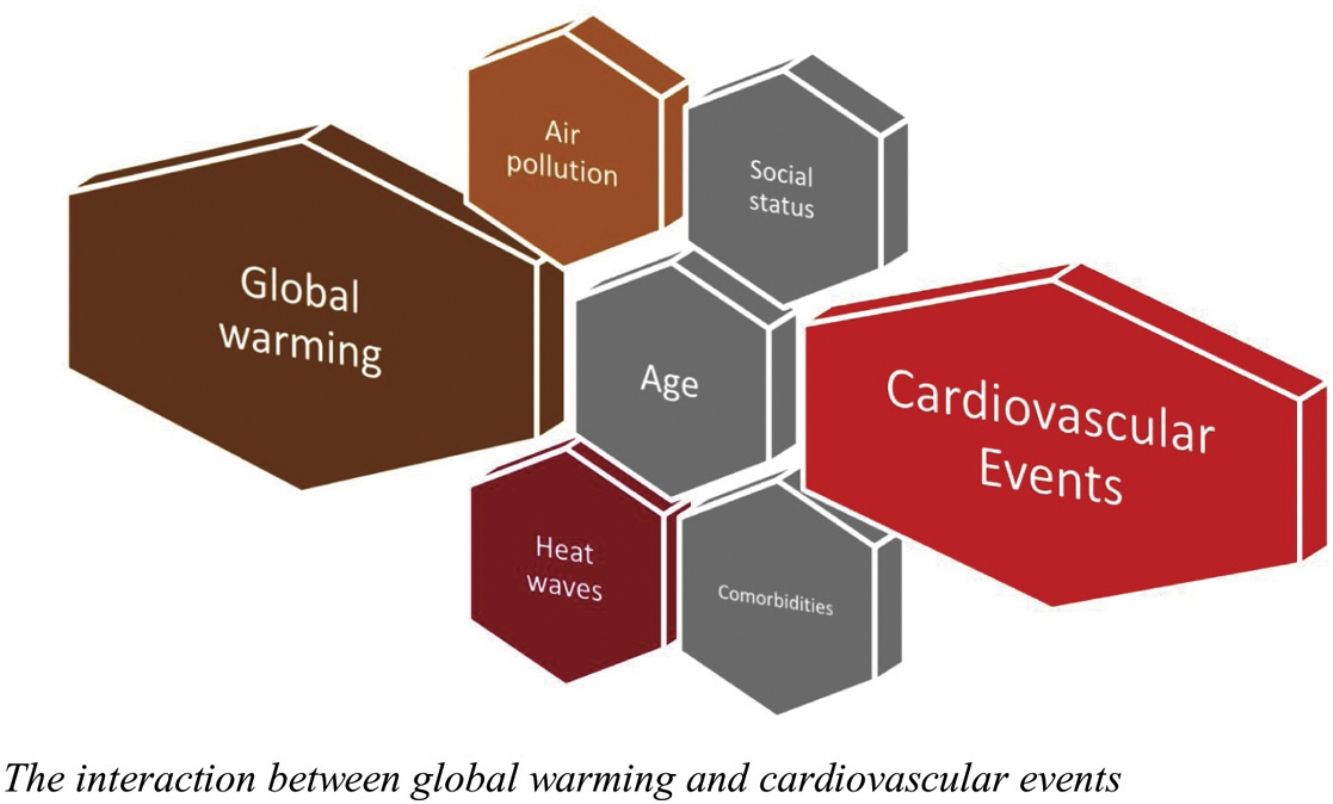

Global warming and the increase in extreme heat events seem to be caused by a dramatic increase in the concentration of gases that promote the greenhouse effect, particularly carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.1 The overall effect is deleterious for nature including biodiversity, food and resources availability and human health. Air pollution plays an important role in the interaction between global warming and several medical conditions, however but the specific contributions of each factor have not been not well established. In cardiovascular diseases, the main cause of death worldwide, air pollution, increases the risk of cardiovascular events.2 Environmental factors, including global warming, are thought to play a role in the risk of cardiovascular disease and events.3 This information needs to be emphasized so decision-makers can properly acknowledge the potential consequences of climate change. A call to further action is needed to limit global temperature rises and the inherent risks for global and cardiovascular health. This position paper explores the link between global warming and CV diseases, retrieving evidence from systematic reviews on the subject. Its goal is two fold: on the one hand to draw attention to this emerging problem and on the other to issue recommendations for this field.

Global warming and cardiovascular diseaseCold weather has consistently been recognized as a classic trigger for cardiovascular disease, and studies support this association.4,5 Several studies also point to the effect of extreme heat on increasing the incidence of mortality. It is therefore essential to explore the links between this potential risk factor/trigger and cardiovascular disease.

The main mechanisms that explain the global warming and increased temperatures as a cardiovascular risk factor are related to an imbalance of the autonomic nervous system towards an increased sympathetic tone due to thermoregulation mechanisms, blood pressure lowering, and dehydration due to high temperatures. In these circumstances, there is rise in heart rate and cardiac output, which increases myocardial demands. These changes can also induce systemic inflammation and lead to a prothrombotic state, placing additional strain on the cardiovascular system,6 predisposing vulnerable individuals to atherosclerotic plaque rupture and to a subsequent increase in the risk of myocardial infarction. Therefore, the relationship between cardiovascular disease and temperature seems to be U-shaped (or J-shaped). The lower risk nadir has not established and may vary geographically. However, in many locations, it varies between 18 and 20°C.7,8

Patients with heart failure may not be capable of compensating for this increase in sympathetic response, leading to acute heart failure episodes. The association between heat exposure and mortality from respiratory diseases is another possible connection that should not be disregarded. It also suggests that increased temperature may be associated with right heart failure – cor pulmonale type.

Aggregated evidence for the association between increased temperatures (global warming) and cardiovascular eventsIn order to review the association between air pollution and cardiovascular events, a search was performed in MEDLINE and Cochrane databases (CENTRAL and Database of Systematic reviews) to retrieve the aggregated evidence from systematic reviews using Boolean combinations of the keywords “climate”, “heat”, “global warming”, “air pollution”, “coronary disease”, “myocardial infarction”, “stroke”, “heart failure”, as well as some variation of these terms. For each outcome of interest, the authors chose one based on their updating and representativeness.

Three systematic reviews provided the risk estimates for cardiovascular events associated with increased temperature (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Systematic reviews evaluating the impact of temperature and/or heatwaves on cardiovascular morbi-mortality and the interaction with air pollution.

| Systematic review | Design | Location | Exposure | Search date | Studies | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChengEnviron Res2019 | Systematic review of observational studies | 20 countries | Heatwaves | 2018 | 54 | Heatwaves increase the mortality of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases |

| PhungSci Total Environ2016 | Systematic review of time-series studies, case-crossover, cohort studies | Multiples countries | Heatwaves | N/R | 64 | Significant relationship exists between cold exposure, heat waves, and variation in diurnal temperature and the elevated risk of cardiovascular hospitalization |

| LiuLancet Planet Health2022 | Systematic review of observational studies using ecological time series, case crossover, or case series studies | Multiple countries | Increase in temperature; heatwaves | 2022 | 266 | Moderate-to-high quality evidence show that cardiovascular mortality and morbidity are increased in heat exposures |

| Systematic review | Studies/estimates | Interaction of temperature/heat with: | Overall conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analitis et al., 2018PHASE project | Daily values of exposure and health outcome from nine cities across Europe | PM10 and cardiovascular mortality: enhancer | Evidence of interactive effects between heat and the levels of ozone and PM10 in terms of mortality |

| Anenberg 2020 | 39 studies | Air pollution in cardiovascular and respiratory diseases or mortality: enhancer | There is sufficient evidence for synergistic effects of heat and air pollution in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular, and respiratory effects (PM and O3 in particular |

N/R: not reported; PM: particulate matter.

In 2016, Phung et al. published a review of 64 studies examining the dose-response relationship of cardiovascular hospitalization according to the temperature.9 The authors concluded that there was a significant relationship between exposure to the cold, heat waves, and variation in daytime temperature and the risk of cardiovascular hospitalizations.9

Cheng et al. assessed cardiovascular and respiratory morbidity associated with heat waves.10 Using the data from 54 studies performed in 20 countries, we concluded that heat waves were associated with an increased risk of mortality from both cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.10 Patient characteristics associated with increased mortality were advanced age and the presence of coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.10

The largest systematic review with meta-analysis on the effects of heat exposure on CV risks was published in 2022 by Li et al. in Lancet Planet Health.11 This systematic review included 266 studies.8 Heat exposure expressed as an increase of 1°C in temperature was shown to increase the relative risk of overall cardiovascular mortality by 2.1%.11 The risks of death due to coronary artery disease, stroke and heart failure were also increased. The risk of cardiovascular death was high in people aged 65 or older (an increase of 1.7% in the relative risk) compared with those less than 65 years old (an increase of 0.9%). Lower-middle-income countries also presented increased cardiovascular mortality risks compared to high-income countries.11 Regarding cardiovascular morbidity (hospital admissions, emergency department admissions or ambulance call-outs), this outcome was significantly increased by 0.5% (RR 1.005, 95% CI 1.003–1.008), despite the reduction in the incidence of morbidity due to hypertensive disease. Once again, lower-middle income countries had the highest increases in cardiovascular morbidity risk.

The cardiovascular risks of heat waves were also ascertained.11 Heat waves were associated with a significantly increased risk of 11.7% (relative risk (RR) 1.117, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.093–1.141) with a higher risk gradient according to the intensity of the heat wave.

Overall, using the Navigation Guide framework, the authors concluded that the current evidence is of high quality to link high temperatures and heat waves to CV mortality, and moderate quality to link high temperatures and heat waves to CV morbidity.11

Evidence of the interaction between air pollution and temperature and cardiovascular outcomesData suggest that the variation of air pollutants and temperature and its association with cardiovascular outcomes may suffer from confounding bias due to collinearity.12 This means that pollution may influence temperature and vice-versa, varying in the same direction regarding cardiovascular risks.13,14 Nevertheless, there is enough evidence to show that both factors exert an independent or synergistic effect on health outcomes (Table 1).15

It is important to highlight two studies that ascertained the potential interactions between temperature and air pollution in cardiovascular outcomes.16,17

The PHASE project published in 2018 evaluated the daily data of nine European countries (Valencia and Barcelona were the closest cities to Portugal in this study).16 Using a random effect meta-analysis, the authors concluded that higher levels of (a type of inhalable particles, with a diameter of less than 10 μm that constitutes an element of atmospheric pollution) further increase cardiovascular mortality risk due to the temperature rise.16

Anenberg et al. evaluated the evidence qualitatively and concluded that the data from 36 studies were sufficient to determine the existence of synergistic effects of heat and air pollution (particulate matter and ground-level ozone in particular) on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular, and respiratory effects.17

Perspectives about global warming and cardiovascular diseaseGlobal warming has resulted in a 1°C increase in the mean global temperature compared with the pre-industrial period.18

According to the currently available data, global warming has increased the relative risk of cardiovascular mortality by 2%, which is extremely relevant in absolute numbers as cardiovascular mortality has been the leading cause of death worldwide.

One of the consequences of global warming is the extreme heat events that have become more frequent in some regions of the world. For example, in 2018, there was an excess of 220 million individual heat wave exposures compared with the average of 1986–2005.19

The 2003 and 2022 heat waves that occurred in Europe are a good examples. To acknowledge the magnitude of the impact of heat waves, it is estimated that in 2003, more than 70000 deaths resulted from this event, some of which were probably due to cardiovascular causes, with more than one-third occurring in France, Italy and Spain.20 There is also evidence that the number of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests can increase 2.5-fold during a heat wave compared with a reference period.21

Mean temperatures have been increasing at a rate of 0.2°C per decade. However, an acceleration in the temperature increase forecasts a global increment in the relative temperature of 1.5°C for the next decades.18 Keeping global temperature increases below the threshold of 1.5°C may prevent several complications including cardiovascular events and deaths related with heat waves, for example.

One of the pillars of the intervention to reduce the pace of global warming is the reduction of air pollution. The Paris Agreement in 2015 aimed to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible to achieve neutrality in emissions and a zero-carbon policy in the middle of this century. Avoiding air pollution is part of a plan to tackle climate change, aiming at protecting society and patients from global warming, particularly those with a higher vulnerability of (cardiovascular) complications, including the elderly, patients with multiple comorbidities and those with low socio-economic condition.22

The adaptation of society to the global warming threat poses new challenges in different sectors. One remarkable aspect is the reorganization of the urban environment to tackle global warming conditions. Firstly, it is estimated that half the world's population live in urban areas, which are responsible for the consumption of two-thirds of global energy and more than 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions.23 Urban environments are also prone to air pollution/poor air quality, which contributes to the development of cardiovascular disease.2 Cities are also prone to heat island effects.24 The high number of buildings and impervious construction materials, with concomitant loss of trees, green space and reduced ventilation, leads to heat accumulation. A retrospective study evaluating the risk factors contributing to excess mortality during the 2003 heat wave in France found that higher surface temperature in the areas surrounding homes was associated with an increased risk of mortality, while the presence of trees and vegetation was found to be protective.24

At an individual level, despite the absence of robust data on interventions to prevent heat-related cardiovascular disease, it is reasonable to conceive that adaptation to warmer temperatures (particularly in heat waves) can be simple. Individuals should protect themselves from exposure during critical periods, dress lightly and use light bedding and sheets, without pillows. They should stay hydrated by ingesting water, but avoiding the consumption of alcoholic beverages. Individuals, should also use cooling techniques and devices such as air conditioning units.24,25 In some cases, the cooling of homes through passive measures can be crucial to ensure nocturnal rest and recovery. Those with poor mobility and with previous medical conditions/comorbidities were at increased risk of complications, further stressing the concept of vulnerable subgroups that might be the target of priority interventions. It is also advisable to monitor patients for possible drops in blood pressure during heat waves and instruct them on how to proceed to avoid clinically relevant hypoperfusion syndromes (which may include adjustments in drug therapy).

A multidisciplinary collaboration framework should be implemented by policymakers and healthcare professionals, including primary care and public health professionals and physicians of different specialities, including cardiologists, to foster care for the prevention of cardiovascular heat-related complications. Together they can plan potential community interventions and awareness raising campaigns advocating for individual- or community-level interventions and global measures to improve air pollution, climate changes and health outcomes.

These much-needed political changes will reduce the CVD burden for future generations, but we must also consider the immediate implications for preventing and treating cardiovascular diseases. We need to increase awareness and enable patients with CVD to take preventive measures.

Real-world data local evidence of global warming: the case of Lisbon, Portugal (1970–2019)Portugal is well known for its frequent heat waves and their repercussions on human mortality and morbidity. Portugal has had an operational heat wave surveillance system, the first in Europe, since 1999.26 This system was based on the ÍCARO model for Lisbon and was later updated.27 The updated version included knowledge gathered from the prolonged heat wave of 2003 that was felt across Europe, and it was used to improve the model for Lisbon and four regional models covering all of Portugal's mainland.

Currently, there are some variables that reflect the magnitude and frequency of heat waves. One of the indicator is the Excess Heat Factor (EHF), an internationally used indicator, which accounts for the intensity of the temperature and also for the previous days short-term acclimatization/disruption.28 Another group of indicators is composed by the Generalized Accumulated Thermal Overcharge (GATO) indicators which is used in the Portuguese ÍCARO Model/Surveillance System. GATO IV is one of such variables that uses a dynamic threshold across the summer weeks to assess heat waves.27

In 2020, a comparison of the EHF and GATO IV for their predictive power for daily cardiorespiratory mortality in Lisbon (1980–2016) showed that both indicators were good predictors for heat-related mortality, with significant predictive advantages for GATO IV.29

The number of days exceeding the GATO IV and EHF in Lisbon point out the sustained increase and potentially harmful effects across decades (Figure 2A). Supplementary Table 1 show that the four GATO indicators used by the Portuguese ÍCARO models in Lisbon (corresponding to different thresholds increasing in their complexity) and the EHF indicator vary in their magnitudes, but they all show a global increase over the last decades.

Additionally, and using the Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) daily data from Portuguese Stations, in particular of “Lisboa Geofísica” – Station PO000008535 – available at https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/ in November 2022, it is noticeable that there was a long-term overall increase in temperature in Lisbon from 1970 to 2019 (Figure 2B).

In conclusion, there is evidence that for Lisbon (Portugal), temperatures and the number of days of extreme heat potentially-related to mortality have been increasing for the past five decades.

Climate projections for the Lisbon region indicate that there will be a substantial thermal aggravation in all seasons of the year, although more pronounced in autumn and summer, with increases in the maximum temperature from +1.5°C to +3.5°C by 2100.30 These forecasts also include more frequent and persistent heat waves in Lisbon and that heat wave days could increase by +23 days per year at the end of the century. Bioclimatic comfort projections reinforce this trend, revealing a marked decrease in cold discomfort as well as a general worsening of heat discomfort in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. These data led to the effects of heat on human health being prioritized in terms of sector adaptations.30

Position statement/conclusionGlobal warming and heat waves are consequences of the climate and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, including cardiovascular mortality.

Air pollution, particularly prevalent in cities, promotes global warming, increases the risk of cardiovascular events and is an enhancer of the risk for temperature-related cardiovascular events.

Multidisciplinary teams should tackle the increased risk and inequities in heat-related cardiovascular complications. At a higher level, these teams should also advocate, alongside the government and policymakers, the importance of complying with measures that prevent global warming, such as fulfilling the Paris Agreement's targets to mitigate cardiovascular and global health risks.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.