The purpose of this study was to assess the diagnostic yield of current referral strategies for elective invasive coronary angiography (ICA).

MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional observational study of consecutive patients without known coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing elective ICA due to chest pain symptoms. The proportion of patients with obstructive CAD (defined as the presence of at least one ≥50% stenosis on ICA) was determined according to the use of noninvasive testing.

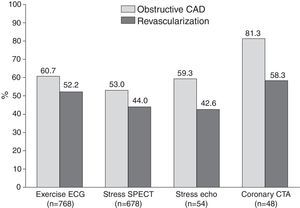

ResultsThe study population consisted of 1892 individuals (60% male, mean age 64±11 years), of whom 1548 (82%) had a positive noninvasive test: exercise stress test (41%), stress myocardial perfusion imaging (36%), stress echocardiogram (3%) or coronary computed tomography angiography (3%). Referral without testing occurred in 18% of patients. The overall prevalence of obstructive CAD was 57%, higher among those with previous testing (58% vs. 51% without previous testing, p=0.026) and when anatomic rather than functional tests were used (81.3% vs. 57.1%, p=0.001). A positive test and conventional risk factors were all independent predictors of obstructive CAD, with adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence interval) of 1.34 (1.03–1.74) for noninvasive testing, 1.05 (1.04–1.06) for age, 3.48 (2.81–4.29) for male gender, 1.86 (1.32–2.62) for current smoking, 1.74 (1.38–2.20) for diabetes, 1.30 (1.04–1.62) for hypercholesterolemia, and 1.39 (1.08–1.80) for hypertension.

ConclusionsMore than 40% of patients without known CAD undergoing elective ICA did not have obstructive lesions, even though four out of five had a positive noninvasive test. These exams were relatively weak gatekeepers; functional tests were more often used but appeared to be outperformed by the anatomic test.

O objetivo do estudo foi avaliar o rendimento das atuais estratégias de referenciação eletiva para coronariografia invasiva.

MétodosEstudo transversal de indivíduos consecutivos sem doença coronária conhecida submetidos a coronariografia por dor torácica. Determinação da prevalência de doença coronária obstrutiva (definida pela presença de pelo menos uma estenose ≥ 50%) de acordo com a utilização de testes não-invasivos para despiste de cardiopatia isquémica.

ResultadosForam avaliados 1892 indivíduos (60% homens, idade média 64 ± 11 anos), dos quais 1548 (82%) tinham um teste não-invasivo positivo: prova de esforço (41%), cintigrafia de perfusão miocárdica (36%), ecocardiograma de stress (3%) e angiografia coronária por tomografia computorizada (3%). Ocorreu referenciação sem teste prévio em 18% dos doentes. A prevalência global de doença obstrutiva foi 57%, sendo mais elevada nos doentes submetidos a testes não-invasivos (58% versus 51% nos doentes sem testes prévios, p = 0,026) e naqueles em que o teste era anatómico versus funcional (81,3% versus 57,1%, p = 0,001). Um teste não-invasivo positivo e fatores de risco convencionais foram preditores independentes de doença obstrutiva, com odds-ratio ajustado (intervalo confiança 95%) de: teste não-invasivo 1,34 (1,03-1,74), idade 1,05 (1,04-1,06), sexo masculino 3,48 (2,81-4,29), tabagismo ativo 1,86 (1,32-2,62), diabetes 1,74 (1,38-2,20), hipercolesterolemia 1,30 (1,04-1,62) e hipertensão 1,39 (1,08-1,80).

ConclusõesMais de 40% dos doentes sem doença coronária conhecida que realizam coronariografia eletiva não têm doença obstrutiva, apesar de quatro em cada cinco ter um teste não-invasivo positivo. Estes testes são gatekeepers relativamente fracos; os funcionais foram utilizados mais frequentemente mas o anatómico pareceu ter melhor desempenho.

coronary artery disease

coronary computed tomography angiography

electrocardiogram

invasive coronary angiography

single-photon emission computed tomography

The evaluation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) is based on clinical assessment, often supplemented by noninvasive tests which serve as gatekeepers for invasive coronary angiography (ICA).1–3 ICA is the diagnostic gold standard for CAD but is costly, has limited availability and carries a risk of complications related to its invasive nature.4 The aims of performing noninvasive testing in this setting include minimizing unnecessary risks and costs, and identifying patients who will benefit from revascularization. However, despite the frequent use of noninvasive testing, a significant proportion of patients undergoing ICA do not have obstructive CAD or are not eligible for revascularization.5,6 The purpose of this study was to assess current patterns of noninvasive testing and to appraise their diagnostic yield among symptomatic patients undergoing ICA for suspected CAD.

MethodsPopulationThis was an observational, cross-sectional study performed at a single hospital center serving an urban population of 900 000 inhabitants in Lisbon, Portugal. The study population consisted of all patients referred for elective ICA for evaluation of chest pain symptoms between January 2006 and November 2010. Patients’ referral for ICA and the decision to perform previous noninvasive testing, including the testing modality, were left to the discretion of attending physicians. Noninvasive testing was performed mostly at private practice facilities.

The modalities of noninvasive testing were exercise electrocardiogram (ECG) stress testing, stress myocardial single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), stress echocardiography and coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA). ‘Ischemic changes’ on the resting ECG were not considered noninvasive testing. The following exclusion criteria were applied sequentially: non-elective setting (acute coronary syndrome), previously known CAD (defined as previous acute coronary syndrome, revascularization procedure or documented coronary stenosis ≥50% on previous ICA), preoperative evaluation, presenting symptom other than chest pain, negative noninvasive test result and incomplete information on patients’ clinical characteristics or ICA result.

Patient evaluationData on demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, type of noninvasive testing and results of coronary angiography were prospectively collected in the ongoing ACROSS (Angiography and Coronary Revascularization On Santa cruz hoSpital) registry, approved by the local ethics committee. The diagnoses of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes (regardless of type, duration or current treatment) were assigned if indicated in the patients’ referral letter or if the patient was being treated with antihypertensive or lipid-lowering drugs, oral antidiabetics or insulin. To avoid underdiagnosis, obstructive coronary was defined as a ≥50% reduction in vessel diameter as compared to a nondiseased proximal segment. This broad definition of obstructive CAD was not used as a criterion for revascularization.

Statistical analysisData are presented as counts (%), medians (interquartile range) or means ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were compared by means of the t test. Patients with and without obstructive CAD were compared for differences in age, gender, body mass index, prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and use of noninvasive testing. Variables that showed significant association with obstructive CAD (p<0.10) in univariate analysis were included in a binary logistic regression model to identify independent predictors. Temporal differences during the study period in the prevalence of obstructive CAD and the use of noninvasive testing were assessed using the chi-square test for trend. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS® version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

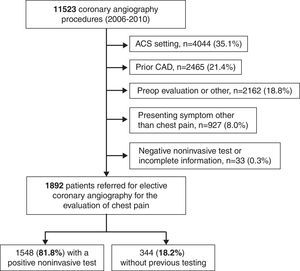

ResultsDuring the study period, 11 523 patients underwent ICA at our hospital. After the exclusion criteria were applied (Figure 1), 1892 patients were included in the analysis.

Most patients (81.8%, n=1548) were referred after a positive noninvasive test. On ICA, the overall prevalence of obstructive CAD was 56.7% (1072/1892). One-vessel, two-vessel or three-vessel/left main disease were identified in 21.1% (n=398), 17.1% (n=323) and 18.6% (n=351) of patients, respectively. The prevalence of obstructive CAD was lower in patients referred without previous noninvasive testing than in those with a positive test (51.2% vs. 57.9%, p=0.026). Myocardial revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or referral for coronary artery bypass grafting) was performed in 46.7% (n=883) of patients.

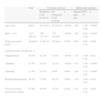

Increasing age, male gender, traditional cardiovascular risk factors and positive noninvasive testing were predictors of obstructive CAD in univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 1).

Population characteristics.

| Total | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Obstructive CAD (n=1072) | No obstructive CAD (n=820) | p | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | p | ||

| Age, years | 64±11 | 65.7±10.4 | 61.7±11.0 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 1.04–1.06 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1141 (60.3%) | 769 (71.7%) | 372 (45.4%) | <0.001 | 3.48 | 2.81–4.29 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.0±3.9 | 27.6±3.9 | 28.0±4.5 | 0.030 | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.240 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, % | |||||||

| Hypertension | 78.4% | 81.3% | 74.6% | <0.001 | 1.39 | 1.08–1.80 | 0.011 |

| Diabetes | 27.5% | 32.5% | 21.1% | <0.001 | 1.74 | 1.38–2.20 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 11.4% | 13.2% | 8.9% | 0.003 | 1.86 | 1.32–2.62 | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 69.2% | 71.9% | 65.7% | 0.004 | 1.30 | 1.04–1.62 | 0.019 |

| Previous positive noninvasive testing | 81.8% | 83.6% | 79.5% | 0.026 | 1.34 | 1.03–1.74 | 0.028 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; CI: confidence interval.

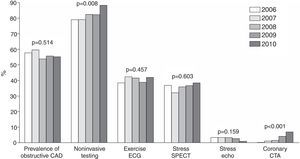

There were no significant temporal differences in the prevalence of obstructive CAD during the study period, despite a significant increase in the proportion of patients undergoing noninvasive testing (Figure 2). Exercise stress testing and stress SPECT were the most used tests, accounting for more than 90% of noninvasive testing. CCTA use increased significantly from 2006 to 2010.

The rates of obstructive coronary artery disease and myocardial revascularization according to type of noninvasive testing are presented in Figure 3. Comparing functional and anatomic tests, the prevalence of obstructive CAD (57.1% vs. 81.3%, p=0.001) was higher in the latter group.

DiscussionDiagnostic yield of the current referral strategyIn our European, urban clinical setting, less than 57% of patients referred for elective ICA for evaluation of chest pain symptoms had obstructive lesions (defined by a broad criterion of ≥50% luminal stenosis), despite the fact that four out of five patients had undergone previous testing. Noninvasive testing was frequently used but was only a weak independent predictor of obstructive CAD (OR 1.34, p=0.028). This apparently low performance of noninvasive tests as gatekeepers for ICA has several possible explanations. One is that the performance of these tests in the “real world” is worse than that reported in the literature from large experienced centers. Another explanation would be a low pretest probability of obstructive CAD in this population, resulting in a relatively large absolute number of patients without obstructive disease undergoing ICA.7 A third hypothesis, supported by increasing evidence,6,8 is that the pretest likelihood of angiographically significant CAD may be overestimated when calculated on the basis of age, gender and chest pain characteristics in accordance with the seminal work of Diamond, Forrester and Pryor.9,10

The yield of any diagnostic test depends on the pretest likelihood of the patients in whom it is used and on the way the test modifies that probability. Ideally, a positive noninvasive test should increase the probability of obstructive disease to a level that justifies performing ICA, and a negative test should reduce that likelihood to a level at which obstructive CAD can be safely ruled out. While ICA will always be performed on some patients without coronary lesions, the 2011 standards for catheterization laboratory accreditation from the Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence organization suggest that the incidence of non-obstructive disease in elective patients should be <40%. In the interests of individual patients and of overall healthcare cost-effectiveness, extreme rates are undesirable. Recently, Genders et al.6 reported a rate of obstructive CAD of 58% (ranging from 39.4% to 75.5%) in a multicenter study involving 11 European hospitals. In the USA, Patel et al.5 reported an overall rate of 41% of patients with obstructive CAD in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, although this varied significantly between different centers, from 23 to 100%.11 Taken together, these studies suggest that better gatekeepers are needed. Our findings are in line with both these studies, underlining the relatively low prevalence of obstructive CAD on ICA in a population with a high frequency of noninvasive testing.

We were also able to assess differences between noninvasive tests. It should be noted that our findings are mainly the result of using functional tests, particularly exercise ECG and stress SPECT, which accounted for more than 90% of testing, as gatekeepers for ICA. Although the proportion of obstructive CAD was higher in the CCTA group than for functional tests, it is uncertain whether the overall results would have been different if anatomic tests had been used more frequently. There is some evidence that CCTA may be a useful and cost-effective gatekeeper for ICA (particularly in patients with intermediate to low pretest probability), reducing the number of patients without obstructive CAD referred for invasive testing.12–19 Recent guidelines for the management of patients with chest pain from the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommend choosing tests according to the pretest probability of CAD. Functional imaging tests are preferred for patients with 30–60% pretest probability of disease, whereas CCTA (preceded by calcium score) is the preferred method for patients with 10–29% pretest probability.20 According to these guidelines, ICA should be offered as the first test to patients with pretest probabilities over 60%. Currently, there is disagreement over which type of test should be used as first line.21 Results from the US National Institutes of Health-sponsored PROMISE study (a clinical endpoint-driven randomized study comparing functional studies with CCTA for the evaluation of patients with suspected CAD) will hopefully shed more light on this matter.22,23

Study limitationsSeveral limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Since the characteristics of chest pain were not systematically assessed and recorded for each patient, it was not possible to calculate the pretest probability of CAD. Although the median age and prevalence of risk factors are compatible with a typical CAD risk population, it is not possible to ascertain whether the weak predictive power of noninvasive testing is related to its application to a population with low pretest probability. Another pitfall is related to the dichotomized classification of noninvasive tests as positive or negative for obstructive CAD. In most tests there is a continuum of ‘positivity’ which is difficult to address with this study design. It should also be emphasized that this was not a randomized trial of noninvasive testing and, as such, direct comparisons of testing vs. no testing and comparisons between noninvasive modalities should be interpreted with caution. The diagnostic performance of noninvasive testing is dependent on the pretest probability of disease, and the decision to perform noninvasive testing and the choice of the test itself depend on the physician's perception of pretest probability, which may have differed between the different diagnostic modalities applied.

ConclusionsNearly half of patients without known CAD undergoing elective ICA due to chest pain did not have obstructive lesions, even though four out of five had a positive noninvasive test. Functional tests were by far the most commonly used gatekeepers but were relatively weak predictors of obstructive CAD and appear to be outperformed by CCTA. There is considerable room for improving the current referral strategy for ICA.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CAD: coronary artery disease; preop: preoperative.' title='Selection of the study population. ACS: acute coronary syndrome;

CAD: coronary artery disease; preop: preoperative.' title='Selection of the study population. ACS: acute coronary syndrome;  CAD: coronary artery disease; CTA: computed tomography angiography;

CAD: coronary artery disease; CTA: computed tomography angiography;  CAD: coronary artery disease; CTA: computed tomography angiography;

CAD: coronary artery disease; CTA: computed tomography angiography;