Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is among the leading causes of morbidity, disability and mortality in Portugal. Despite the considerable decline in cardiovascular mortality as a result of improved healthcare access, diagnostic testing, new pharmacological treatments and regulatory measures, such as the new tobacco law, CVD remains the number one cause of mortality in women and is second to cancer in men.1 It is estimated that 75% of CVD cases are attributable to modifiable cardiovascular (CV) risk factors,2 thus meaning CVD can be prevented, treated, and controlled.3 Given the considerable economic, social and cultural impact of CVD,4 the need for health promotion and disease preventive strategies adapted to population characteristics is undeniable. Consecutive national health plans have been designed to meet this goal.

The 2020 Portuguese National Health Plan was created by the Portuguese Ministry of Health. This document establishes the course of intervention within the framework of the health system, prioritizing measures for health gains in the Portuguese population. Its major goals are the increase of healthy life expectancy and the reduction in premature mortality.5 However, much emphasis was placed on short-term financial issues which jeopardizes the response to future challenges.

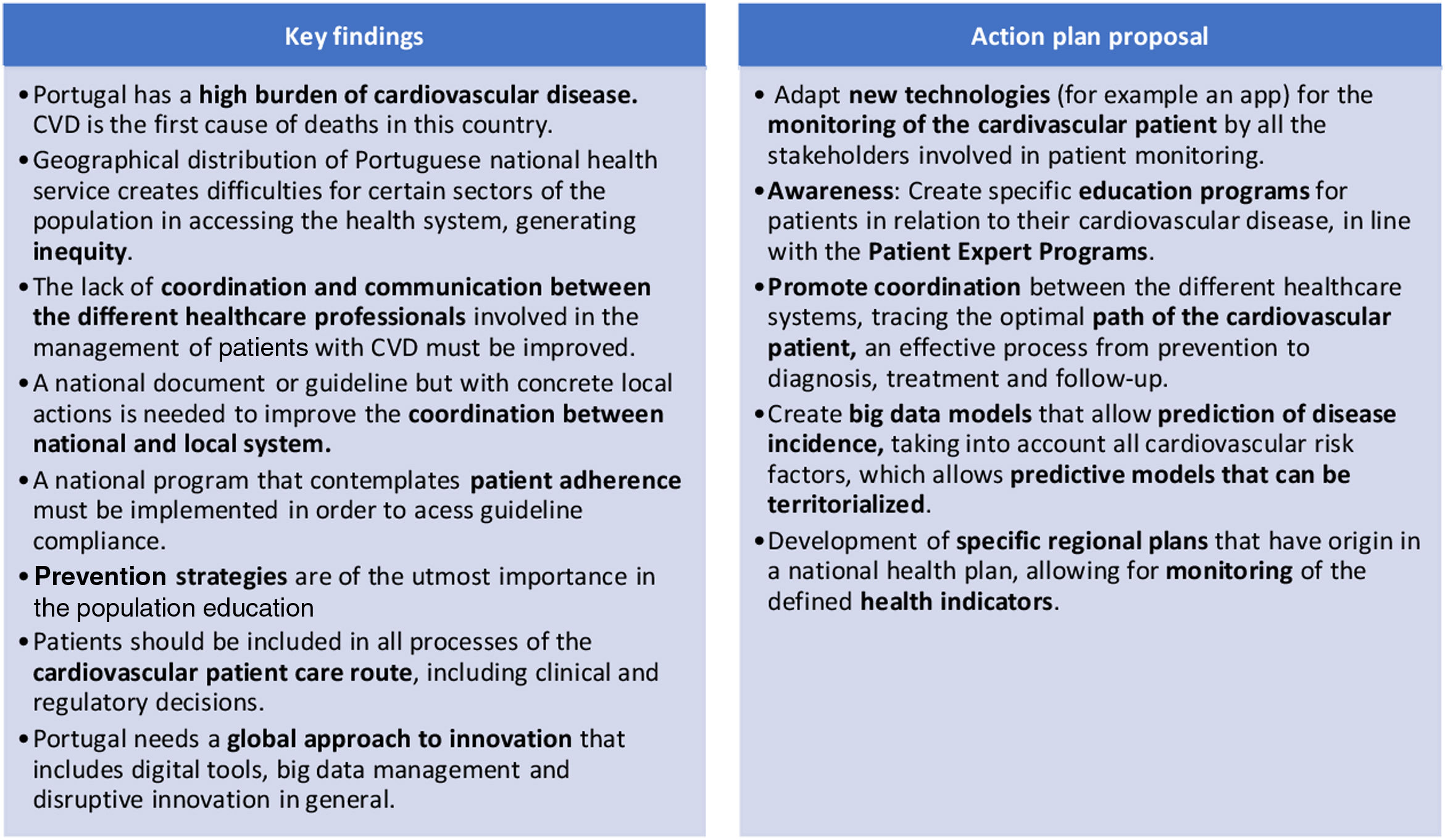

Based on their high level of clinical and academic expertise and experience in the Portuguese political health sector, the authors were challenged to create a think tank, from which a proposal of new measures, related to CVD, which addresses current and future health challenges could emerge. The improvement in care provision, patient education, treatment adherence and innovation were some of the topics covered.

Context and healthcare organizationIn Portugal, CVD manifests more frequently as cerebrovascular disease, followed by coronary disease. Prevention programs about modifiable CV risk factors and improvement of health literacy are key points to be controlled.

The organization of the national health system is subject to discussion, not only because of the agglomeration of hospitals in coastal regions and major cities but also because of the division of health administration services into five regions. This sub-segmentation of health administration services not only results in different approaches to health management, but also complicates the coordination between institutions. Moreover, there is a problem with the digital interface at health institutions including primary care, endangering adequate patient follow-up. The problem is especially striking when it comes to private institutions as they do not share patient information with other institutions through a digital platform.

Routes of careThink tank members argued for the need for better coordinated and accessible circuit for patients. There are several barriers to setting up such a circuit. According to the experts, one of the most relevant barriers is human resources, which directly affect time and motivation to patient education. The existence of adequate number and distribution of different healthcare professionals would also help to improve multidisciplinary work. To facilitate patient follow-up, team coordination must be enhanced within the institution and between different hospitals and community centers.

Think tank members were also of the opinion that a substantial change in the management of healthcare services is required to be able to rely on high-quality primary care. Also, healthcare professionals must be provided with a national health plan, a document or guidelines at national level with concrete actions at local level that can be uniformly applied all over the country and enable teamwork. Such a plan would encourage consistent primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention measures. Transparent leadership and coordination are pivotal to achieve these targets.

Adherence and educationPatient education must be promoted at every opportunity, referred to as comprehensive, opportunistic and proximity medical care by healthcare professionals by the World Health Organization, but this itself may not be enough. In fact, it was found in a recent study on specific knowledge about CVD, that there were important gaps in knowledge among the Portuguese population.6 Think tank members highlighted the importance of structured education programs in which patient associations must be involved and primary medical doctors empowered. Media and social networks could be used according to the target age group. Wide spread eHealth and mHealth practices with the use of common devices, such as smartphones, can be used to improve patient self-management and adherence.

Adherence to treatment is essential to meet prevention and treatment goals. Portugal does not have a program for monitoring patient adherence to therapy, although it could be designed taking into account the strategic position of the pharmacist, in close proximity with patients. However, it was decided that patients must take responsibility for their own health and manage their disease. Ensuring that patients know the rationale for their medications and the consequences of non-compliance is essential to increasing adherence. Whenever possible, strategies such as combination pills or polypills or simple electronic reminders should be used for this purpose.

Other critical factor is related to the still wide gap between the state-of-the-art knowledge and its implementation in clinical practice, as shown in recent surveys, such as the EUROASPIRE III, IV, V and, it has been stated by OECD and the EU as an important missed opportunity to improve the care of patients.7–10 Ultimately, there are several major factors, which play a significant role in the healthcare management of CV patients in Portugal, far beyond patient adherence such as ease of access, clinical inertia or drug financing procedures.

InnovationThe concept of process management must evolve to meet future goals, which must be based on cost-effectiveness issues. The opinion of patients, their families and career-related demands are increasingly being considered. Parameters related to patient reported outcomes should also be included health technology, assessment, supporting decisions on prices and reimbursement of innovative technologies.

Innovation in health technology has been advocated as one of the most promising improvements in the NHS. Digital health tools can be used in prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and follow-up. Such innovation can be disruptive, changing the paradigm of action in healthcare. The COVID19 pandemic created an inevitable opportunity to test tools such as tele-consultation and remote patient education, which were proven to be effective. Overall, and despite some user related obstacles, Portugal is considered an innovative country. Financial planning is key to supporting innovation. Technology can be useful not only for the individual patient, but also to be used on a larger scale. Big data management can generate predictions valuable for future health management. In the absence of a national strategy, a remarkably interesting initiative emerged from the Portuguese Society of Cardiology, the National Cardiology Data Collection Center (CNCDC). The CNCDC was established to facilitate the development of studies on cardiovascular disease involving all different elements of the Portuguese health system.11

The discussion of the current healthcare picture has identified several challenges that must be addressed (Figure 1). The solutions proposed by this think tank may be helpful for Government decisions and most certainly more obstacles will be encountered on the path to progress. Recent patient negligence during the pandemic, either due to lack of hospital response or to fear-related abandonment, exposed many weaknesses in the national health service. Reconciling economic and financial issues with well-experienced expert opinion will be the key to successful improvement of healthcare management for cardiovascular patient. Despite the important topics already highlighted, further discussion is required in order to find new formulas and strategies to balance financial sustainability with access to innovative technologies to improve healthy CV parameters in the Portuguese population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.