Cardiac hemangiomas are an exceedingly rare condition, with about 100 cases described in the literature, of which only 13 were valvular.

We report the case of a 66-year-old woman, with no prior cardiovascular disease, who presented with an abdominal infection caused by Enterococcus faecalis, complicated by recrudescent fever and new-onset systolic mitral murmur. The transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a large vegetation on the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve, with a high embolic risk, leading to a diagnosis of acute endocarditis. The patient began antibiotics, with no clinical improvement, developing severe heart failure and coronary and cerebrovascular embolic phenomena, and underwent excision of the mass and placement of a biological mitral prosthesis. The histopathologic analysis revealed a cavernous hemangioma.

Eight months later, the patient presented with recurrence of acute bacterial endocarditis and septic shock, and underwent replacement of the prosthetic valve. The histologic exam showed no signs of hemangioma.

The rarity of this case and its complications make its presentation relevant.

O hemangioma cardíaco é uma patologia cuja extrema raridade tem tornado difícil o seu estudo, encontram-se descritos na literatura apenas cerca de 100 casos, dos quais apenas 13 são valvulares. Descrevemos o caso de uma doente de 66 anos, sem antecedentes de doença cardiovascular, que se apresentou com quadro infeccioso por Enterococcus faecalis com ponto de partida abdominal, complicado por febre recrudescente e aparecimento de sopro sistólico mitral de novo. O ecocardiograma transesofágico revelou uma vegetação no folheto posterior da válvula mitral, com elevado risco embolígeno, que levou ao diagnóstico de endocardite aguda. Foi iniciada antibioterapia, sem melhoria clínica, evoluiu com insuficiência cardíaca e fenómenos de embolização coronária e cerebrovascular, pelo que foi submetida a excisão da massa e colocação de prótese mitral biológica. A análise histológica revelou um hemangioma cavernoso.

Oito meses depois, verificou-se novo episódio de endocardite bacteriana aguda, sem isolamento de agente, com evolução em choque séptico e necessidade de reintervenção cirúrgica, com substituição da válvula protésica. O exame histológico não mostrou recidiva da neoplasia.

A raridade deste caso e as suas complicações tornam pertinente a sua exposição.

Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with an estimated incidence between 0.0017% and 0.28%.1 Myxoma is the most common, accounting for 50% of benign tumors, a similar figure to that reported in a Portuguese series from 1994 to 2007 of 41 cardiac tumors diagnosed by echocardiography, of which 65.85% were myxomas.2 In another Portuguese series of 123 patients with cardiac tumors treated surgically between 1994 and 2014, 12 cases (9.8%) were malignant, most (67%) of them sarcomas.3

Hemangiomas, benign vascular tumors, account for only 2.8% of cardiac tumors.4 They may occur at any age, but are most often diagnosed in the fourth decade of life. Surgical case series of cardiac hemangiomas reveal a predominance of male gender (around 65%).5,6 They may be sessile or polypoid and are small (2-3 cm). Although usually isolated, they may be associated with other hemangiomas, cutaneous or visceral.

Cardiac hemangiomas can be classified macroscopically according to the structural layer affected7 (endocardium, myocardium, epicardium or pericardium, the first two being the most common), or according to the cardiac chamber involved (right ventricular wall in 36%, left ventricle in 34% and right atrium in 23%, the remainder being located in the interventricular septum or left atrium).

Microscopically they are characterized by benign proliferation of moderately pleomorphic endothelial cells with few mitoses, sometimes with atypical nuclei.4 Five types have been described: cavernous, capillary and ateriovenous hemangioma, hemangioendothelioma, and hemangioma with papillary endothelial hyperplasia,8 with different histologic types frequently occurring together. Fibrous tissue and adipocytes are also found.

Most cases are asymptomatic and are diagnosed as an incidental finding during autopsy or cardiac surgery for a different condition. Clinical presentation is determined by various factors including location, size, growth rate and potential for embolization or invasion, and can include arrhythmias, heart failure, outflow tract obstruction, peripheral embolization or acute coronary syndrome.

The clinical course is highly variable; the tumor may proliferate indefinitely, stop growing, or in some cases undergo complete spontaneous regression.6,9

Surgery is the recommended treatment for symptomatic cases and has excellent long-term results.10,11

We describe the case of a patient with a large cardiac mass, initially diagnosed with infective endocarditis, in whom histologic analysis revealed the presence of a cavernous hemangioma of the mitral valve, and present a brief review of the literature on this rare condition.

Case reportWe report the case of a 66-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, obesity and bilateral saphenectomy and no relevant family history or habits. She presented with fever, generalized myalgia, non-specific malaise, non-selective anorexia and choluria lasting for several weeks. Acute cholangitis was suspected and she was started on empirical piperacillin/tazobactam, which resulted in clinical improvement and apyrexia within 48 hours and improvement of inflammatory parameters. Etiologic investigation revealed a lesion on abdominal echography in the second part of the duodenum, which was further studied by computed tomography and abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, showing a heterogeneous nodular formation with poorly defined boundaries compatible with a large duodenal diverticulum. Blood cultures revealed amoxicillin- and gentamicin-sensitive Enterococcus faecalis and antibiotic therapy was accordingly changed to ampicillin and gentamicin.

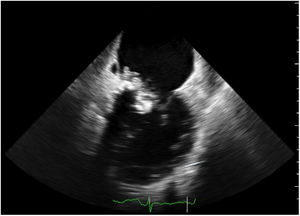

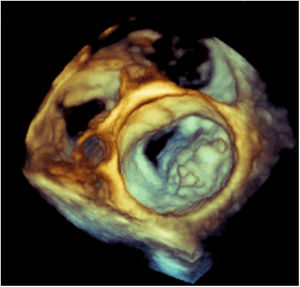

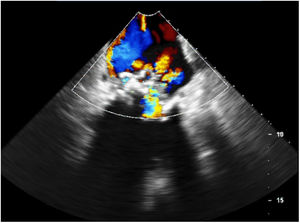

Three days later, the fever returned and a new systolic mitral murmur was observed. Repeat blood cultures were negative. The transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a large mass (19.2 mm×28.3 mm) at the level of the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve, suggestive of vegetation, with high embolic risk (Figures 1 and 2 and Videos 1 and 2), causing moderate compromise of left ventricular filling and moderate to severe eccentric mitral regurgitation toward the interatrial septum (Figure 3 and Video 3). In the following hours the patient developed acute heart failure (NT-proBNP 33 872 mg/dl) and acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (peak troponin I 5.47 ng/ml) and cerebrovascular embolic phenomena.

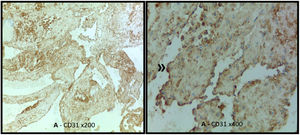

Due to her unfavorable clinical course, the patient was referred for urgent cardiac surgery. Via a transseptal approach, a dark red vegetative mass was observed attached to the annulus and posterior leaflet of the mitral valve (P2/P3) that extended to the posterior wall of the left ventricle with apparent destruction of endocardial tissue. A 29-mm St. Jude Epic biological mitral valve was implanted and the left ventricular posterior wall was reconstructed with a bovine pericardial patch. The postoperative repeat transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a properly functioning prosthetic valve and normal valve gradients with no identifiable leaks, and no vegetations or images suggestive of abscess or fistula. Histopathologic analysis of the mass revealed a sample consisting of fragments of the mitral valve deformed by coarse calcifications, together with a benign neoplastic vascular lesion with a proliferation of cavernous vascular spaces and numerous aggregates of fibrin, erythrocytes and granulocytes, compatible with a cavernous hemangioma (Figure 4). Cultures were negative, so given the previous isolation of the probable agent and the impossibility of excluding acute bacterial endocarditis concomitant with cardiac hemangioma, it was decided to maintain the antibiotic therapy already prescribed and a total of four weeks of directed therapy were completed, with a good outcome. The patient was discharged clinically stable and referred for echocardiographic follow-up.

Eight months later, she was admitted once more with prolonged febrile illness associated with progressive fatigue on slight exertion, which evolved to mixed cardiogenic and septic shock (no agent was isolated), with multiple organ dysfunction and need for surgical reintervention. Intraoperatively the prosthetic valve was seen to be almost completely obstructed by a large brownish vegetation with a wart-like appearance, just reaching the mitral annulus. The valve was replaced with a new biological valve with a good final result and with no postoperative complications. Histologic examination revealed synthetic material partly covered with pannus together with adhering fibrin and abundant neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate, with some bacterial aggregates but no signs of neoplasia.

The patient completed four weeks of antibiotic therapy with vancomycin, gentamicin and rifampicin, which was uneventful. She remained clinically stable for the following two years with no echocardiographic evidence of regression.

DiscussionCardiac valves are essentially avascular, which means that valvular hemangiomas are extremely rare, with only 13 cases reported in the literature.12–18 Cardiac hemangioma has generally been little studied and very few surgical series on the condition have been published.

The initial presentation of the case reported here was an abdominal infection with bacteremia positive for Enterococcus faecalis, complicated by infective endocarditis of the mitral valve, in a patient without risk factors or known cardiovascular disease. The echocardiographic image was initially suggestive of a large vegetation but turned out to be a cavernous hemangioma. Development of heart failure and coronary and cerebrovascular embolic phenomena, in addition to being known common complications of endocarditis, are also the most frequent manifestations of this benign tumor.19,20 Other reported complications include hemodynamic alterations secondary to valve involvement and acute coronary syndrome, which were also seen in this case. Presentation as endocarditis ‘grafted’ onto a hemangioma has been described and cannot be excluded in this patient, possibly associated with increased tissue factor levels (an essential stimulus for the formation of vegetations21,22), and may in this context have been of bacterial (including enterococcal) or tumoral origin, or induced by endothelial injury. Since the patient was already under antibiotic therapy, the question remained as to the possibility of non-infective endocarditis, hence it was decided to maintain this therapy for two more weeks, in accordance with the available evidence.23 On the other hand, concomitant acute thrombosis is also a possibility; this has been observed occasionally in the context of coagulopathy associated with this benign tumor, with a rare case report of a giant cardiac hemangioma manifesting as Kasabach-Merritt syndrome.24

Mitral location of hemangioma is extremely rare, described in only 2% of one case series.6 Histologically, cavernous hemangioma is one of the two most common types of cardiac hemangioma, the other being the capillary type.

Laboratory parameters are non-specific. Echocardiography is the most commonly used diagnostic tool and remains the most suitable exam to screen for cardiac tumors,25 confirming the diagnosis in 81% of cases,10 even though there are in fact no established echocardiographic criteria.

Computed tomography is usually the second-line exam for the study of cardiac masses, but incidental findings are increasingly common given its frequent use in the assessment of coronary disease.26,27 Like magnetic resonance imaging,28 in which hemangiomas demonstrate intense gadolinium enhancement, it has proved very useful in preoperative assessment for precise localization of the mass, including its relationship with the cardiac chambers and involvement with the myocardium, pericardium and neighboring structures. In the present case, these exams were not performed due to the suspicion of acute endocarditis complicated by the need for urgent surgery.

Since our patient was symptomatic, she was referred for cardiac surgery, which was performed without complications and with almost complete recovery of her baseline functional status. For unknown reasons, intracavitary and intramyocardial hemangiomas have a potential risk of medium-term recurrence, especially if resection is incomplete29, as in the case described, and therefore regular echocardiographic follow-up was scheduled. However, despite the recurrence of acute bacterial endocarditis of the prosthetic valve, no sign of recurrent hemangioma has been detected to date.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingNo grant or subsidy was awarded for the preparation of the present work.

The following are the supplementary material to this article: