Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a rare form of dilated cardiomyopathy that is associated with high maternal morbidity and mortality. Onset is usually between the last month of pregnancy and up to the fifth month postpartum. PPCM usually presents with signs and symptoms of heart failure and rarely with thromboembolic complications. The true incidence of thromboemboli in PPCM is unknown. Herein we report an unusual case of PPCM in a previously healthy woman who presented with recurrent transient ischemic attacks due to thrombus in the left ventricle.

A miocardiopatia periparto (MPP) é uma forma rara de miocardiopatia dilatada, associada a elevada mortalidade e morbilidade materna. A doença manifesta-se habitualmente entre o último mês de gravidez até ao 5.° mês depois do parto. A MPP apresenta-se habitualmente com sinais e sintomas de insuficiência cardíaca e, raramente, com complicações tromboembólicas. A verdadeira incidência de tromboembolismo na MPP não é conhecida. Apresentamos um caso, pouco habitual, de MPP em mulher previamente saudável que se apresentou com acidentes isquémicos transitórios recorrentes, devido à presença de trombo no ventrículo esquerdo.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a rare form of dilated cardiomyopathy that is associated with high maternal morbidity and mortality.1 Onset is usually between the last month of pregnancy and up to the fifth month postpartum.2 PPCM usually presents with signs and symptoms of heart failure and rarely with thromboembolic complications. The true incidence of thromboemboli in PPCM is unknown.3 Herein we report an unusual case of PPCM in a previously healthy woman who presented with recurrent transient ischemic attacks due to thrombus in the left ventricle.

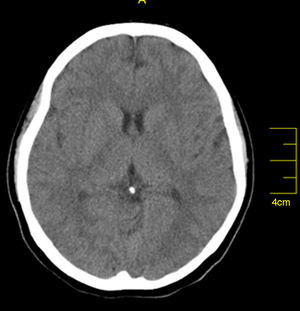

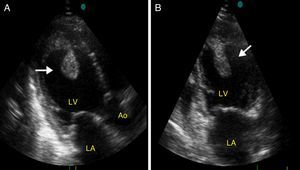

Case reportA 27-year-old primigravida woman presented in the emergency room seven days after an uncomplicated spontaneous vaginal delivery. She complained of recurrent temporary speech disturbance and visual impairment twice within six hours. The pregnancy was uneventful and her medical history was insignificant. On physical examination, blood pressure was 110/65 mmHg with a regular heart rate of 105 bpm. Bilateral grade 1–2 pitting pedal edema was present. Carotid auscultation and fundoscopic evaluation were normal. Chest auscultation showed bibasal crackling rales less than one-half way up the posterior lung fields and an apical III/VI systolic murmur with S3 gallop. The electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm. The chest X-ray on admission showed cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema with bilateral pleural effusion. Urgent neurologic investigation with computed brain tomography revealed no evidence of ischemia (Figure 1). The patient was diagnosed with transient ischemic attack. Laboratory tests, including coagulation studies with platelets, D-dimers, prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time, were within the normal range except for BNP, which was elevated (1300 pg/ml; normal <100 pg/ml) and C-reactive protein (0.30 mg/dl; normal <0.5). The thyroid hormone profile was normal. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed global left ventricular hypokinesia, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension of 65 mm with an ejection fraction of 22% (by Simpson's method) and moderate mitral regurgitation. A large mobile mural thrombus was observed in the left ventricular apex (Figure 2A and B). Screening for thrombophilia including antithrombin III, protein C and S, plasminogen, fibrinogen and homocysteine levels was normal and antiphospholipid antibodies, β2-glycoprotein I and anticardiolipin antibodies IgG and IgM were negative. Factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210A polymorphism and MTHFR mutations were not found. The patient was immediately started on intravenous anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin as well as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics and digoxin. A beta blocker (carvedilol) was added after signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure improved. By one month of follow up she had responded well to medical therapy and was asymptomatic; repeat TTE showed no evidence of thrombi in the left ventricle and ejection fraction had improved to 38%.

DiscussionPPCM is a disorder of unknown origin that has potentially devastating consequences, presenting in the last month of pregnancy or in the first five months postpartum with signs and symptoms of systolic heart failure and a fatality rate of 20%–50%. It is defined according to the following four criteria: (1) development of cardiac failure in the last month of pregnancy or within five months of delivery; (2) absence of an identifiable cause for the cardiac failure; (3) absence of recognizable heart disease prior to the last month of pregnancy; and (4) left ventricular systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction <45% or reduced shortening fraction <30%).1,2

The exact etiology remains unknown. PPCM presents with signs and symptoms of heart failure and rarely with thromboembolic complications.3 The occurrence of thromboembolism is probably due to multiple reasons, such as the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy, cardiac dilatation and dysfunction, endothelial injury and venous stasis.2 Although the most common presentation is signs and symptoms of heart failure, PPCM can be obscured by the pregnancy early in its course and diagnosed from complications such as hepatic failure due to congestion or thromboembolism due to left ventricular thrombus, as in the present case.4 Our patient was admitted to hospital with neurologic symptoms due to left ventricular thrombus, and no symptoms of heart failure. Since delayed diagnosis can be associated with increased morbidity and mortality, any woman in the peripartum period with neurologic symptoms should undergo an echocardiographic evaluation to detect left ventricular thrombus, even in the absence of a clinical presentation of heart failure.

In conclusion, transient neurologic impairments during the last month of the pregnancy or in the early postpartum period may be the only sign of PPCM. Thus, a high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose atypically presenting PPCM to prevent life-threatening complications by early initiation of anticoagulation.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.