According to the current guidelines for treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should be performed within 90min of first medical contact and total ischemic time should not exceed 120min. The aim of this study was to analyze compliance with STEMI guidelines in a tertiary PCI center.

MethodsThis was a prospective single-center registry of 223 consecutive STEMI patients referred for primary PCI between 2003 and 2007.

ResultsIn this population (mean age 60±12years, 76% male), median total ischemic time was 4h 30min (<120min in 4% of patients). The interval with the best performance was first medical contact to first ECG (median 8min, <10min in 59% of patients). The worst intervals were symptom onset to first medical contact (median 104min, <30min in 6%) and first ECG to PCI (median 140min, <90min in 16%).

Shorter total ischemic time was associated with better post-PCI TIMI flow, TIMI frame count and ST-segment resolution (p<0.03). The three most common patient origins were two nearby hospitals (A and B) and the pre-hospital emergency system. The pre-hospital group had shorter total ischemic time than patients from hospitals A or B (2h 45min vs. 4h 44min and 6h 40min, respectively, p<0.05), with shorter door-to-balloon time (89min vs. 147min and 146min, respectively, p<0.05).

ConclusionsIn this population, only a small proportion of patients with acute myocardial infarction underwent primary PCI within the recommended time. Patients referred through the pre-hospital emergency system, although a minority, had the best results in terms of early treatment. Compliance with the guidelines translates into better myocardial perfusion achieved through primary PCI.

Segundo as recomendações atuais para o tratamento do enfarte agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST a intervenção coronária percutânea deve ser efetuada dentro de 90min após o primeiro contacto médico e o tempo total de isquémia não deve exceder os 120min.

O objetivo deste trabalho foi analisar a adequação da implementação destas recomendações para o enfarte do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST num centro terciário de intervenção coronária percutânea.

MétodosRegisto prospetivo de centro único de 223 doentes consecutivos referenciados para intervenção coronária percutânea primária entre 2003 e 2007.

ResultadosNesta população (idade média 60±12 anos, 76% de sexo masculino), a mediana do tempo total de isquémia foi 4h 30min (<120min em 4% dos doentes). O intervalo de tempo com menor atraso foi desde o primeiro contacto médico até à realização do ECG (mediana 8min, <10min em 59% dos doentes). Os intervalos com maior atraso foram: do início dos sintomas ao primeiro contacto médico (mediana 104min, <30min em 6% dos doentes) e do primeiro ECG à realização da intervenção coronária (mediana 140min, <90min em 16% dos doentes). O menor tempo total de isquémia associou-se a melhor fluxo TIMI final, melhor TIMI frame count final e maior resolução do segmento ST após angioplastia (p<0,03).

As 3 origens mais frequentes dos doentes foram: 2 hospitais de localidades próximas e o sistema de emergência médica pré-hospitalar. No grupo pré-hospitalar verificou-se menor tempo total de isquémia que nos hospitais A ou B (2h 45min versus 4h 44min e 6h 40min, p<0,05), com menor tempo desde o primeiro contacto médico até à angioplastia (89min versus 147 e 146min, p<0,05).

ConclusãoNesta população, apenas uma reduzida percentagem de doentes com enfarte agudo do miocárdio obteve tratamento adequado por angioplastia primária dentro dos tempos recomendados. Os doentes referenciados pelo sistema de emergência pré-hospitalar, embora em reduzida percentagem do total, foram os que obtiveram os melhores resultados na precocidade do tratamento. O cumprimento das recomendações traduz-se em melhores resultados na perfusão miocárdica obtida pela angioplastia primária.

The treatment of choice for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is early reperfusion, whenever possible by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), since numerous studies have shown its superiority over thrombolysis, with better immediate and long-term outcomes.1 Any delay in reperfusion can lead to a worse prognosis. In-hospital mortality following primary PCI rises from 3.0% to 4.8% with door-to-balloon times of 30min and 180min, respectively,2 and 12-month mortality increases by 7.5% for each 30-min delay.3

Current guidelines stress the importance of minimizing the delay between symptom onset and reperfusion. The European Society of Cardiology recommends reperfusion through primary PCI as early as possible in STEMI patients who present within 12h of symptom onset and have persistent ST-segment elevation (or presumed new complete left bundle branch block) on 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) (class I recommendation, level of evidence A).4 The delay between first medical contact (FMC) and primary PCI should be ≤2h in any STEMI patient and ≤90min in those who present within 2h of symptom onset, or with extensive anterior STEMI and low risk of bleeding (class I recommendation, level of evidence B).4

Similarly, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend that STEMI patients who come to primary PCI-capable hospitals should be treated within 90min of FMC (class I recommendation, level of evidence A), and total ischemic time should not exceed 120min.5

Furthermore, given the importance of 12-lead ECG in this context, this should be performed within 10min of FMC in patients who present with chest discomfort.6 Similar guidelines have been adopted by national medical societies; in Portugal the delay in transferring patients to a PCI-capable center should not exceed 30min.7

The aim of this study was to analyze the treatment of STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in a tertiary hospital, by assessing delays at different stages of treatment until primary PCI.

MethodsFrom the Angioplasty and Coronary Revascularization On Santa Cruz hoSpital (ACROSS) prospective registry, which includes all consecutive patients undergoing PCI in this tertiary center since 2002, we selected 223 consecutive STEMI patients who underwent primary PCI between 2003 and 2007. The diagnosis of STEMI was established in patients with acute chest pain lasting over 30min and ST-segment elevation in at least two contiguous leads on 12-lead ECG or new complete left bundle branch block.

Total times and intervals between symptom onset and primary PCI were analyzed and compared with the guidelines.

The following time intervals were defined prospectively and compared with recommended times: pain-to-FMC – symptom onset to FMC (recommended time [RT]<30min); FMC to diagnostic ECG (RT<10min); ECG-to-PCI center – diagnostic ECG to arrival at PCI center (RT<30min); PCI center-to-balloon – arrival at PCI center to first balloon inflation (RT<50min); ECG-to-balloon – diagnostic ECG to first balloon inflation (RT<80min); FMC-to-balloon – FMC to first balloon inflation (RT<90min); and total ischemic time – symptom onset to first balloon inflation (RT<120min). These time intervals were defined in accordance with Portuguese and international guidelines.4–7

The population was divided into three groups based on patient origin: hospital A (6km from the center), hospital B (22km from the center), and the pre-hospital emergency system. The time intervals under study were then compared between groups.

The following parameters of myocardial perfusion were also assessed: TIMI flow, TIMI frame count and ST-segment resolution following PCI. TIMI flow and TIMI frame count were calculated in accordance with published reference studies.8,9 ST-segment resolution was evaluated on the basis of the sum of all leads presenting ST elevation on the diagnostic ECG. These variables were used as surrogate markers of PCI success when the following were observed: TIMI 3 flow, TIMI frame count ≤24 and ST-segment resolution ≥70%. Differences in total ischemic time were compared in the presence and absence of these markers of successful PCI.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means±standard deviation, except for time intervals, presented as medians.

Differences between continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis tests, a value of p<0.05 (95% confidence interval) being considered significant.

ResultsThe mean age of the selected population of 223 patients was 60±12years, and 76% were male. The following cardiovascular risk factors were present: diabetes in 17% of patients, smoking (current or former smoker) in 56%, hypertension in 55% and dyslipidemia in 50%. At presentation, 7% were in Killip class ≥III, while 18% had a history of myocardial infarction, 19% of PCI, 4% of coronary artery bypass grafting and 5% of cerebrovascular disease, and 2% had renal failure requiring dialysis.

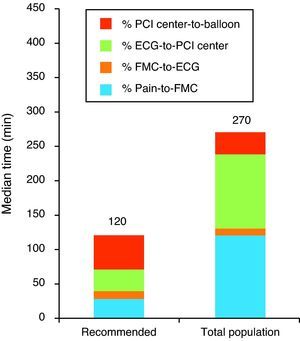

Total time and other intervals are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. The median total ischemic time was 4h 30min, with only 4% undergoing PCI within 120min.

Median times in the overall population compared to maximum recommended times.

| Max RT | Observed | < Max RT (%) | |

| Pain-to-FMC | 0h 30min | 1h 45min | 6.0 |

| FMC-to-ECG | 0h 10min | 0h 08min | 58.5 |

| ECG-to-PCI center | 0h 30min | 1h 34min | 7.0 |

| PCI center-to-balloon | 0h 50min | 0h 30min | 75.2 |

| ECG-to-balloon | 1h 20min | 2h 03min | 18.3 |

| FMC-to-balloon | 1h 30min | 2h 20min | 16.0 |

| Total ischemic time | 2h 00min | 4h 30min | 3.7 |

ECG-to-balloon: diagnostic ECG to use of first balloon inflation; ECG-to-PCI center: diagnostic ECG to arrival at PCI-capable center; FMC-to-balloon: first medical contact to use of first balloon inflation; FMC-to-ECG: first medical contact to diagnostic ECG;

Median total time and other time intervals in the overall population compared with maximum recommended times. ECG-to-PCI center: diagnostic ECG to arrival at PCI-capable center; FMC-to-ECG: first medical contact to diagnostic ECG; Pain-to-FMC: symptom onset to first medical contact; PCI center-to-balloon: arrival at PCI-capable center to first balloon inflation; Recommended: maximum recommended time.

The intervals with the best performance were FMC-to-ECG, with a median of 8min (<10min in 59% of patients), and PCI center-to-balloon, with a median of 30min (<50min in 75%). The worst intervals were pain-to-FMC, with a median of 104min (<30min in 6%), and FMC-to-balloon, with a median of 140min (<90min in 16%).

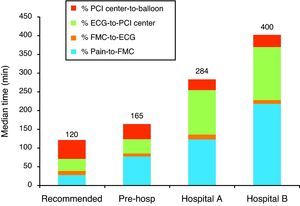

The most common patient origin was hospital A (64%), followed by hospital B (15%) and the pre-hospital emergency system (9%). The remaining 12% came from other health institutions or arrived directly at our center by their own means. Total time and other intervals for each group are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The pre-hospital group had shorter total ischemic time than patients from hospitals A and B (2h 45min vs. 4h 44min and 6h 40min, respectively, p<0.05), which was mainly due to shorter pain-to-FMC time (75 vs. 107 and 152min, p<0.05) and shorter ECG-to-PCI center time (36 vs. 106 and 99min, p<0.05).

Median times compared to maximum recommended times according to patient origin.

| Max RT | Pre-hospital | Hospital A | Hospital B | ||||

| Observed | < Max RT (%) | Observed | < Max RT (%) | Observed | < Max RT (%) | ||

| Pain-to-FMC | 0h 30min | 1h 15min | 7.1 | 1h 47min | 5.0 | 2h 32min | 8.3 |

| FMC-to-ECG | 0h 10min | 0h 07min | 71.4 | 0h 13min | 48.3 | 0h 06min | 64.7 |

| ECG-to-PCI center | 0h 30min | 0h 36min | 33.3 | 1h 46min | 3.4 | 1h 39min | 0 |

| PCI center-to-balloon | 0h 50min | 0h 44min | 62.5 | 0h 27min | 88.7 | 0h 24min | 84.6 |

| ECG-to-balloon | 1h 20min | 1h 22min | 50.0 | 2h 20min | 6.1 | 2h 22min | 6.3 |

| FMC-to-balloon | 1h 30min | 1h 29min | 64.3 | 2h 27min | 2.0 | 2h 26min | 4.3 |

| Total ischemic time | 2h 00min | 2h 45min | 6.7 | 4h 44min | 1.0 | 6h 40min | 0.0 |

ECG-to-balloon: diagnostic ECG to first balloon inflation; ECG-to-PCI center: diagnostic ECG to arrival at PCI-capable center; FMC-to-balloon: first medical contact to first balloon inflation; FMC-to-ECG: first medical contact to diagnostic ECG;

Median total and other time intervals compared with maximum recommended times according to patient origin. ECG-to-PCI center: diagnostic ECG to arrival at PCI-capable center; FMC-to-ECG: first medical contact to diagnostic ECG; Pain-to-FMC: symptom onset to first medical contact; PCI center-to-balloon: arrival at PCI-capable center to first balloon inflation; Pre-hosp: pre-hospital emergency system; Recommended: maximum recommended time.

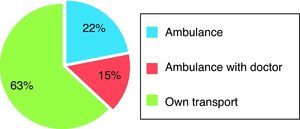

Of the total population, 203 patients were not referred directly to our center by the pre-hospital emergency system, and 63% of these arrived at the hospital by their own means, while the other 37% were transported by ambulance (with pre-hospital medical assessment in at least 15% of these) (Figure 3).

With regard to PCI outcomes, TIMI 3 flow was obtained in 83% of patients, TIMI frame count ≤24 in 59%, and ST-segment resolution ≥70% in 45%. Successful PCI based on these surrogate markers was associated with shorter total ischemic time: median total ischemic time in patients with TIMI 3 flow was 4h 17min (vs. 7h 03min in those with TIMI 2 flow, p=0.02); in those with TIMI frame count ≤24 it was 4h 11min (vs. 5h 00min in those with TIMI frame count >24, p=0.03); and in those with ST-segment resolution ≥70% it was 3h 59min (vs. 5h 12min in those with ST resolution <70%, p=0.02) (Table 3).

Median total ischemic times according to surrogate markers of successful PCI.

| Total ischemic time | p | |

| TIMI 2 vs. 3 | 7 h 03min vs. 4h 17min | 0.02 |

| TIMI frame count >24 vs. ≤24 | 5 h 00min vs. 4h 11min | 0.03 |

| ST resolution <70% vs. ≥70% | 5 h 12min vs. 3h 59min | 0.002 |

TIMI: TIMI flow after PCI; TIMI frame count: corrected TIMI frame count after PCI.

The link between the duration of myocardial ischemia and prognosis in the context of STEMI has been clearly established and achieving myocardial reperfusion as rapidly as possible is now a priority. Indeed, in recent years, the focus of STEMI treatment has been to reorganize health services so as to provide treatment with the minimum delay.

A study by Le May et al.10 analyzed time intervals defined in a similar way to ours: ECG-to-PCI center (median 38min), PCI center-to-balloon (median 57min), ECG-to-balloon (median 104min) and total ischemic time (median 201min). The times observed in that study were shorter than those found in our population, with the exception PCI center-to-balloon time, probably the result of greater delay in patients arriving at our center, thus giving more time to organize the logistics and PCI team. The study also compared differences in times between patients referred directly via a pre-hospital system and those from other hospitals. As in our study, all the time intervals were significantly shorter when patients were referred directly via a pre-hospital system. Median delays for this subgroup were similar in both studies, but Le May et al. reported a significantly higher proportion of patients referred from a pre-hospital environment (39% vs. 9% in our study), which could explain the greater delays observed in our population.

Another study analyzing STEMI patients referred for primary PCI by pre-hospital teams found that in 66.7% of cases the time between FMC and PCI was <90min,11 which is similar to the FMC-to-balloon time observed in our pre-hospital group.

In a multicenter study combining information from 30 countries,12 the time reported from symptom onset to FMC (defined as performance of diagnostic ECG) varied between 60 and 210min, and from FMC to balloon between 60 and 177min. The delays found in our population are around the middle of the range in that study.

With regard to Portugal, a study by Trigo et al.13 reported median pre-hospital delays between 3h 31min and 4h 05min, slightly longer than in our study. On the other hand, median in-hospital delays ranged between 1h 26min and 2h 15min, slightly shorter than found in our population. The differences may be related to organizational differences between the two centers: our hospital's referral area is smaller (resulting in shorter pre-hospital delays) but it has no on-site emergency department and thus most referrals come from other hospitals (resulting in longer in-hospital delays). Another study, by Ribeiro et al.,14 analyzed pre-hospital delays in this context, reporting a median of 2.16h, similar to our population. Lastly, Ramos et al.15 observed a median total ischemic time of 7.64h (12.1h in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock), slightly longer than in our patients.

We found shorter delays in patients referred for PCI via the pre-hospital emergency system. However, a significant proportion of the remaining patients had been assessed by medical personnel before being transported to a non-PCI capable hospital. These patients had either not undergone pre-hospital ECG or if they had, a diagnosis of STEMI had not been made.

Analysis of surrogate markers of successful myocardial reperfusion following PCI revealed an association between shorter total ischemic time and better final TIMI flow, lower final TIMI frame count and greater ST-segment resolution. This suggests that shorter total ischemic time results in a higher probability of successful PCI. Similar findings have been observed in other studies that report an association between shorter ischemic time and better primary PCI outcome as assessed by corrected TIMI frame count.16 We found no mention in the literature of an association between shorter ischemic time and better TIMI flow or greater ST-segment resolution after primary PCI for STEMI. However, these parameters have been thoroughly studied as markers of successful PCI.17,18 The association found in our study between better PCI outcome based on these markers and shorter ischemic time highlights the importance of prompt reperfusion in STEMI.

ConclusionThis study shows that, despite the availability of a 24-h pre-hospital emergency system and the fact that patients with myocardial infarction referred via this system present significantly shorter total ischemic times, only a small percentage of patients actually use it, confirming that the attitude of patients with STEMI plays a crucial role in outcomes and compliance with guidelines. The longest delays were in pain-to-FMC and FMC-to-balloon times, the latter being attributable to the internal organization of hospitals.

In this population, only a minority of STEMI patients were revascularized within the recommended time limits. The responsibility for the delays observed would appear to be multifactorial, related not only to the failure of patients to seek immediate medical assistance when experiencing chest pain but also to organizational aspects of the different health systems involved.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sousa, P. ICP primária no enfarte de miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST: tempo para intervenção e modos de referenciação. Rev Port Cardiol. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.repc.2012.07.006