We describe the case of a patient with acute bioprosthesis dysfunction in cardiogenic shock, in whom hemodynamic support was provided by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and successfully treated by transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Apresentamos o caso de um doente com disfunção aguda de bioprótese em choque cardiogénico com suporte hemodinâmico através de oxigenação da membrana extracorporal (vaECMO) e tratado com sucesso através de implantação percutânea da válvula aórtica (TAVI).

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is used to treat high-risk patients with bioprosthetic valve degeneration (valve-in-valve technique). We describe the case of a patient with acute bioprosthesis dysfunction in cardiogenic shock, in whom hemodynamic support was provided by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and successfully treated by TAVI.

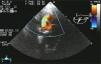

Case reportA 62-year-old Caucasian male underwent conventional aortic valve replacement using a stented bioprosthesis (standard 23 mm Carpentier-Edwards Perimount) six years ago, as suggested by the cardiac surgeons, in order to avoid oral anticoagulation. Transthoracic echocardiography performed six months before admission showed normal left ventricular ejection fraction with a normally functioning aortic bioprosthesis and slightly elevated gradients (mean pressure gradient 18 mmHg). The patient was referred to the emergency department of our hospital in cardiogenic shock complicated by pulmonary edema (Figure 1) and was immediately treated with diuretics and high-dose inotropes to achieve stabilization.

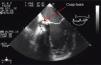

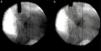

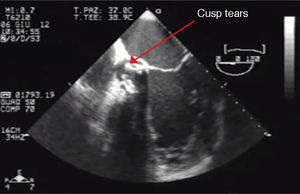

Eventually transesophageal echocardiography was performed, showing severe eccentric aortic regurgitation (Figures 2 and 3, Video 1) due to prosthesis degeneration and cusp tears (Figure 4, Video 2) together with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (about 20%).

The presence of active endocarditis was ruled out by a completely normal blood count, a procalcitonin value within normal limits and negative blood cultures.

In view of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) predicted 30-day mortality score of 13% and a EuroSCORE II of 28%, our heart team decided on urgent TAVI, with a valve-in-valve procedure through a transapical approach.

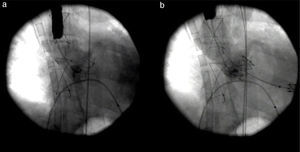

Due to life-threatening cardiogenic shock, miniaturized venoarterial ECMO was used as a bridging therapy to stabilize the patient, and on the following day he underwent TAVI with a 26 mm SAPIEN aortic bioprosthesis through a left anterior minithoracotomy by a transapical approach (Figure 5).

There were no periprocedural complications and following progressive hemodynamic improvement, the ECMO was removed on day two after TAVI.

The patient's clinical course was favorable and uneventful, and he was discharged to a cardiac rehabilitation facility two weeks after the procedure.

At three-month follow-up, the patient was in stable clinical conditions, in New York Heart Association class II, with improved left ventricular ejection fraction (about 40%), no significant aortic regurgitation and a mean transprosthetic gradient of 13 mmHg.

DiscussionWe believe there are several important issues in our case. Firstly, the prophylactic use of venoarterial ECMO during TAVI procedures is only anecdotal and there are no data on its systematic use, particularly in the context of a valve-in-valve redo operation.

Nonetheless, there are favorable reports on the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in very high-risk patients with cardiogenic shock to achieve hemodynamic stability during TAVI.1 Similarly, modern ECMO has been used as a bridging therapy in cardiogenic shock. Specifically, Husser et al. report that in the event of procedural complications in TAVI, emergency implantation of venoarterial ECMO for circulatory support appears feasible to stabilize the patient for additional treatment, the best results being achieved with prophylactic venoarterial ECMO in patients with exceedingly high perioperative risk; procedural success and 30-day mortality in patients with prophylactic compared to emergency venoarterial ECMO was 100% vs. 44% and 0% vs. 44%, respectively.2

Another interesting aspect of our report, besides bridging therapy, lies in the pathophysiology of bioprosthesis dysfunction, i.e. cusp perforation, which was rare in a series by Forcillo et al.3 reporting long-term follow-up of Carpentier-Edwards aortic bioprostheses in patients undergoing valve replacement for prosthesis dysfunction. In their series, only 21% showed evidence of cusp tear, which is the rarest cause of prosthesis dysfunction, less frequent than dehiscence, endocarditis, stenosis or calcification.3

Cusp perforations and tears are primarily related to calcification, hemodynamic stress and valve tissue deterioration4 and often cause acute valve failure, as in our patient.

Elective conventional redo aortic valve surgery has an operative mortality from 2% to 7%, but this can rise to 30% in high-risk, hemodynamically unstable patients.5

Moreover, redo surgery is also associated with increased morbidity and prolonged recovery. Given the less invasive nature of TAVI, the procedure appears to be a suitable interventional option, particularly for patients who present with a degenerated and failing bioprosthetic valve.

Although severe LVEF depression (<20%) and hemodynamic instability have been considered absolute contraindications for TAVI,6 this option, with either a transapical or transfemoral approach, has been proven feasible, safe, and associated with hemodynamic improvement in patients not eligible for conventional surgery. D’Ancona et al. performed transapical TAVI on 21 patients in acute cardiogenic shock, achieving technical procedural success in all patients, with an acceptable early mortality (19% at 30 days). However, the observed one-year survival of 46%7 represents a suboptimal outcome compared to that of non-cardiogenic shock patients undergoing valve-in-valve TAVI8 but is still better than the outcome observed after conventional aortic valve replacement.5

Transapical access has been adopted in the majority of procedures on failing aortic bioprosthetic valves. In high-risk patients, however, a transfemoral approach may be preferred for a better safety profile since mechanical ventilation is not required and it is clearly less invasive.

In our case the transapical route was preferred to take advantage of some technical aspects, such as better control and fine adjustment during valve placement. Crossing a stented bioprosthesis is easier via the transapical route and is independent of the size of the peripheral vessels; additionally, it should be emphasized that the disease affecting the implanted valve can have varying effects on internal diameter, including thickening of the tissue leaflets, calcification and pannus growth, reducing the internal diameter of the stent and making the placement of a valve-in-valve prosthesis via a femoral approach wide harder to perform. The Edwards SAPIEN valve presents advantages with respect to the CoreValve, notably the balloon-expandable system, which has better sealing and lower risk of embolization.

In conclusion, TAVI in association with CPB or venoarterial ECMO may emerge as a valuable treatment option in inoperable patients with acute severe prosthesis dysfunction and become an acceptable alternative to surgical redo in a selected group of non-elderly patients with high surgical risk. However, before TAVI can be recommended in this subset of patients, the risk of periprocedural complications (especially conduction abnormalities and stroke) and long-term percutaneous valve durability in patients with longer life expectancies should be taken into consideration.

The combined use of TAVI and venoarterial ECMO in our patient represented an innovative and clinically acceptable compromise solution to a complicated surgical and medical issue, the challenge being whether to perform an emergency redo or first to stabilize this relatively young and shocked patient. In this acute prosthesis failure scenario venoarterial ECMO may be helpful in establishing hemodynamic stabilization and may give time for the choice of the preferred strategy of valve-in-valve TAVI.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.