The authors report a case of multiple pulmonary varices, a rare disease characterized by aneurysmatic venous dilatations, which can be present at any age and without gender predominance, occurring in isolation or associated with obstruction of the pulmonary veins. This condition usually manifests as a lung mass with variable clinical consequences.

Relata-se um caso de varizes pulmonares, na sequência diagnóstica realmente ocorrida. É patologia rara, em que a dilatação venosa aneurismática pode ser isolada ou associar-se a obstruções venosas, ocorrendo em qualquer idade, e sem predomínio de gênero. Frequentemente manifesta-se como massa pulmonar a esclarecer e apresenta repercussão clínica variável.

We present the case of a 34-year-old female patient with six pregnancies, four deliveries and two miscarriages (G6P2A4), with a history of slowly progressive dyspnea over the previous six years, associated with chest oppression and occasional syncope. In the last two pregnancies she noticed worsening of dyspnea during minimum exertion (New York Heart Association class IV) and generalized postpartum edema. On physical examination her heart rate was 90 bpm and blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg and she had normal pulses in all four limbs, precordial thrust in the lower left sternal border and a loud second heart sound without murmurs. Lung auscultation revealed no adventitious bruits, and there was no edema, ascites or hepatic splenomegaly.

Laboratory tests showed hematocrit 35%, hemoglobin 11.7 g/dl, GOT 316 U/l, GPT 143 U/l, and TSH 147 μIU/l. Arterial blood gas testing on room air revealed pH 7.42, pO2 76.8 mmHg, pCO2 33.8 mmHg, O2 sat 94.9%; serological tests for Chagas disease, HIV and hepatitis were negative, as were anti-NF, rheumatoid factor, anti-SCL-70, anti-HIV, anti-HBsAg and anti-HCV tests.

Functional pulmonary testing showed forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) 2.06 l (75% predicted); forced vital capacity (FVC) 2.39 l (68% predicted); VEF1/FVC 0.86 (109% predicted); total pulmonary capacity 4.65 l (94% predicted); residual volume 2.06 l (predicted 143); diffusing capacity: 1.616 ml/mmHg (75% predicted).

Cardiopulmonary testing revealed peak oxygen uptake 10.8 ml/kg/min; respiratory exchange ratio 1.28; VE/VCO2 slope 56; and exercise oscillatory ventilation.

The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with right atrial and right ventricular dilatation and hypertrophy and nonspecific repolarization abnormalities.

The chest X-ray demonstrated cardiomegaly with dilation of the right chambers and enlarged pulmonary vessels, more evident in the lung bases.

On echocardiography, there was moderate dilation of the right cavities with diffuse right ventricular hypokinesia, paradoxical septal motion, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and dilatation of the pulmonary trunk and main branches. Pulmonary hypertension was detected with peak systolic pressure of 87 mmHg.

Following diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension by echocardiography, the patient was referred to our catheterization laboratory for characterization of pulmonary hypertension and study of pulmonary vascular reactivity.

Cardiac catheterization and pulmonary angiography revealed pulmonary artery pressure of 70/40/50 mmHg; right ventricular pressure 70/08/15 mmHg; mean right atrial pressure 15 mmHg with increased V wave (20 mmHg); mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure in both lungs 10 mmHg; left ventricular pressures 100/02/10 mmHg; and aortic gradient: 100/60/73 mmHg.

Cardiac output was 2.1 l/m/m2 and pulmonary vascular resistance index was 9 Wood units/m2; the patient was unresponsive to vascular reactivity testing administering 100% O2 and nitric oxide up to 80 parts per million.

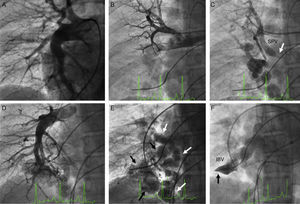

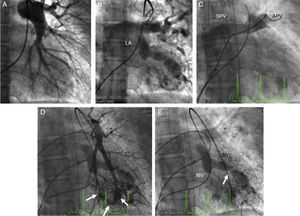

A transseptal puncture was then performed followed by selective contrast injection in the pulmonary veins, and a left atrial and venous pressure gradient of 10 mmHg was measured. The pulmonary angiogram (Figures 1 and 2) showed bilateral varicose dilatation of the inferior pulmonary veins, more prominent in the right lung. The right lung presented varices in the veins of the middle and inferior lobes, severe obstruction of the superior pulmonary vein at its junction with the left atrium, and occlusion of the inferior basilar vein. The left lung presented varices in the lingula and inferior lobe, occlusion of the apicoposterior vein and inferior basilar vein and severe obstruction of the superior basilar vein.

(A) Right pulmonary arteriography showing dilatation of this branch with normal peripheral vessels; (B) selective injection in the superior right pulmonary artery; (C) pulmonary venous return with significant obstruction of the superior vein (arrow) and collateral vessels to the inferior vein with presence of multiple varices; (D) selective injection in the right inferior pulmonary artery; (E) pulmonary venous return showing dilatation and twisting of the central veins of the middle and inferior lobes; (F) complete obstruction of the inferior basilar vein (arrow). IBV: inferior basilar vein; SPV: superior pulmonary vein.

(A) Left pulmonary arteriography showing dilated central and thin peripheral vessels; (B) venous return to the left atrium; (C) complete obstruction of the apical posterior vein (arrow); (D) inferior lobe arteriography and venous return showing dilatation and twisting of the central veins (arrows); (E) obstruction of the inferior and superior basilar veins. APV: apical posterior vein; IBV: inferior basilar vein; IPV: inferior pulmonary vein; LA: left atrium; SBV: superior basilar vein; SPV: superior pulmonary vein.

Chest computed tomography following cardiac catheterization and angiography demonstrated pulmonary hypertension with right ventricular overload and images of bilateral varices, more prominent in the right lung, in both segments of the middle lobe and the mid and posterior segments of the inferior lobe, with severe obstruction of the superior pulmonary vein at the junction with the left atrium. In the left lung, varices of the veins of the lingula and anterior and lateral segments of the inferior lobe were observed.

The patient was treated with sildenafil 25 mg three times daily, oral anticoagulation, intrauterine device implantation and inclusion in the cardiopulmonary transplantation program.

DiscussionPulmonary varix is a rare pulmonary venous disorder, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature, originally described by Puchet in 1843 at autopsy of a child who died from intestinal bleeding and who also presented multiple varices in other organs. The next five cases (Hedinger-Basel, 1907; Nauwerck, 1923; Klinck and Hunt, 1933; Neiman, 1934; Jacchia, 1936) were also autopsy findings; Mouquin et al. reported the first angiographic description in a living patient in 1951.1

Pulmonary varices can be congenital or acquired, and isolated or associated with varices in other organs. Congenital varices develop during the embryonic period and may coexist with various congenital heart diseases. Acquired forms are associated with diseases with increased pulmonary vein pressure such as mitral valve disease or distal occlusion of the pulmonary veins, liver cirrhosis or emphysema.2–5 Even when associated with pulmonary venous hypertension, there must be a concomitant histological weakness in the vein wall, since pulmonary varicosities are infrequent in the presence of those more common disorders. In cases of mitral regurgitation, the most affected veins are those of the right inferior lobe, probably due to the preferential direction of retrograde flow, and varices can regress after valve replacement or repair.5,6

The criteria for angiographic diagnosis were established by Bartram et al.7 and more recently by Berecova et al.8: (1) normal pulmonary arteries; (2) absence of pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae; (3) simultaneous filling of varicose and normal veins; (4) varices draining into the left atrium; (5) prolonged emptying compared to normal veins; (6) the dilated and tortuous varices are central, near the hilum, with normal peripheral veins.

In a review of 71 published cases, Uyama et al.9 classified pulmonary varices in three types: (1) saccular type, localized, oval or saccular dilatation; (2) tortuous type, twisted, elongated dilatation; and (3) confluent type, dilatation in the confluence of the pulmonary veins.

In our patient, the varices were possibly congenital because although they were associated with pulmonary vein stenosis, these obstructions were located in non-varicose veins. The varices in this case were central, twisted and elongated, and the peripheral veins were normal. Drainage of the occluded varices was to the left atrium, although there were some collateral vessels from the superior to the middle and inferior lobes of the right lung.

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first case reported of association of pulmonary varix with primary pulmonary hypertension, another congenital disease.

The differential diagnosis of pulmonary varices includes other conditions with dilatation of the pulmonary veins, including pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas, and hepatopulmonary and scimitar syndromes.8,10

Congenital pulmonary varices are usually asymptomatic and do not require treatment, but annual monitoring with imaging studies should be considered. In some cases, dysphagia and middle lobe syndrome may be present, due to compression of the esophagus and bronchi, respectively. The main complications of pulmonary varices are rupture, hemoptysis, and thrombosis with systemic embolism, and treatment is directed to prevent these events. Our approach was oral anticoagulation, intrauterine device implantation, pharmacological treatment for pulmonary hypertension and inclusion in the cardiopulmonary transplantation program.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.