Among cardiovascular diseases, pericardial disease has specific characteristics. Its etiology, diagnosis and medical management are not as well understood as in coronary and valvular heart disease. In most cases, its cause is benign, although the proportion decreases with more severe clinical presentation.

The authors present the case of a 35-year-old man with no relevant past medical history, who went to the emergency department with what appeared to be an idiopathic case of acute pericarditis. However, over the following five months, there was an unfavorable evolution to constrictive pericarditis, requiring pericardiectomy. The final diagnosis was only made following surgery – a rare case of a primary pericardial tumor, a mesothelioma.

As doenças do pericárdio apresentam-se como uma patologia particular do foro cardiovascular. Os seus componentes etiológicos e a gestão diagnóstica e terapêutica não estão tão bem compreendidos e estudados, comparativamente com outras áreas, como a doença coronária ou valvulopatias. Maioritariamente, a etiologia é benigna, mas a sua proporção diminui à medida que a apresentação e evolução clínicas são mais exuberantes.

Os autores descrevem um caso de um homem de 35 anos de idade, sem antecedentes clínico-patológicos de relevo conhecidos, que se apresenta num Serviço de Urgência com o que aparenta ser um episódio de pericardite aguda de etiologia idiopática. Contudo, ao longo de cinco meses, evolui desfavoravelmente, com necessidade de orientação para pericardiectomia por pericardite constritiva. Apenas no bloco operatório foi feito o diagnóstico etiológico final. Tratava-se de um caso muito raro de neoplasia primária do pericárdio, um mesotelioma.

The etiology and management of pericardial disease are often unclear, since they do not enjoy the consensus surrounding other types of cardiovascular disease. However, prognosis is generally favorable and invasive intervention or extensive investigation is usually unnecessary.1

Malignant primary cardiac tumors are rare, particularly those originating in the pericardium, which is more likely to be affected by metastases.2 Thus, defining the typical clinical presentation and diagnostic and medical management are hindered by the scarcity of cases described in the literature.2

Case reportA 35-year-old man, Caucasian, a construction worker, with no relevant past medical history and taking no regular medication, went to the emergency department in November 2008 for persistent crushing chest pain radiating to the shoulders and worsening on deep breathing and in dorsal decubitus; he had no other symptoms and no abnormalities on physical examination. The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm, diffuse concave ST-segment elevation and PR-segment depression in the inferior leads. Laboratory tests and chest X-ray were within normal parameters. A diagnosis of idiopathic acute pericarditis was made, and the patient was medicated with intravenous aspirin, which improved his symptoms. He was prescribed aspirin, discharged home and referred for cardiology consultation. On assessment a month later, he was asymptomatic and echocardiography showed a moderate pericardial effusion but no other significant changes. He was prescribed colchicine and ibuprofen.

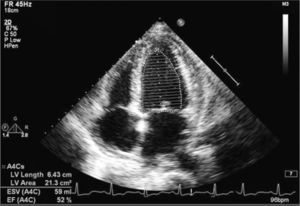

Four months later, in February 2009, he again went to the emergency department for interscapular pleuritic pain and new-onset dyspnea on moderate exertion of 15 days’ evolution. Cardiac auscultation was normal; pulmonary auscultation revealed decreased breath sounds and vocal fremitus in the right lung base, and jugular venous distension at 45°, with no Kussmaul sign or paradoxical pulse. Echocardiographic reassessment (Figure 1) showed preserved biventricular systolic function and no dilatation, with pericardial thickening and a small circumferential effusion of organized appearance, and no significant variation in transvalvular flow over the respiratory cycle. The electrocardiogram revealed diffuse T-wave inversion but no ST- or PR-segment alterations. Laboratory tests were similar to the previous results and the chest X-ray showed a small right basal pleural effusion. The patient was admitted for investigation of the organized pericardial effusion which appeared to be evolving to constrictive pericarditis of unknown etiology.

Thorough etiological study, including thoracentesis, screening for sepsis (serology for infectious agents, blood cultures and microbiological analysis of pleural fluid), tuberculin test and thyroid function, was negative. Thoracic, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography was also performed, which showed diffuse pericardial thickening with no significant effusion, enlarged paratracheal lymph nodes (28 mm maximum diameter), apparently of an inflammatory nature, and bilateral pleural effusion, more pronounced on the right. The patient was referred for cardiac catheterization, which showed elevation and equalization of atrial and ventricular diastolic pressures (32 mmHg), with intraventricular pressure curves showing the square root sign and respiratory variation suggestive of ventricular interdependence, but no angiographic coronary artery or valve disease. Pericardiocentesis was not performed since the pericardial effusion was not significant and thus the window to perform it safely was small. The patient was discharged home, clinically improved, with a diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis, to await early elective pericardiectomy. However, he again suffered clinical worsening with decompensated heart failure and episodes of intense retrosternal pain associated with hypotension, and was readmitted a week after discharge.

During this hospitalization, therapeutic thoracentesis was performed twice for marked pleural effusion (more severe on the right), as well as colonoscopy due to new-onset abdominal pain with rectal bleeding, which revealed friable, congested and bleeding sigmoid mucosa, histologically compatible with ischemic colitis.

The patient was transferred to a referral surgical center (five months after onset of the clinical setting) for pericardiectomy. Intraoperatively, a fibrotic and infiltrative neoplastic process was observed in the heart, more marked in the right atrium and great vessels, making resection impossible. In view of the patient's hemodynamic instability, requiring invasive vasopressor and ventilatory support, he was transferred to the intensive care unit. Control echocardiography showed moderate biventricular systolic dysfunction with paradoxical interventricular septal motion, a moderately large pericardial effusion and significant respiratory variation in transmitral flow. The patient died three days later.

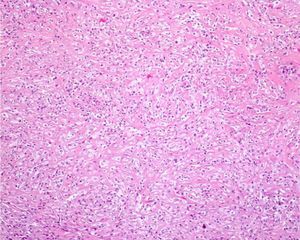

Anatomopathological study revealed a malignant epithelial neoplasm with a storiform pattern and trabecular areas, as well as spindle cells (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical analysis showed immunoreactivity of the tumor cells to cytokeratin 7 and AE1/AE3 and multifocal areas positive for calretinin and cytokeratin 5, which, together with the absence of pleural involvement, led to a final diagnosis of a primary pericardial biphasic mesothelioma.

DiscussionPericardial disease is not uncommon and diagnosis does not usually require invasive methods; however, determining its precise etiology remains a challenge. Less severe clinical manifestations such as acute pericarditis or small pericardial effusions (often an incidental finding) are generally idiopathic but presumed to be of viral origin in most cases, and prognosis is favorable. In more severe clinical presentations such as recurrent pericarditis, chronic moderate to large pericardial effusions, pericardial tamponade or constrictive pericarditis, idiopathic etiology is still the most common but in a lower proportion of cases.1 Invasive strategies including pericardiocentesis must therefore be carefully weighed against the risk of complications. This diagnostic, and sometimes therapeutic, procedure is reserved for patients with pericardial tamponade or chronic moderate to large pericardial effusions or when there is suspicion of severe disease (purulent pericarditis or neoplasia, as long as there is a safe window to perform the technique).1

Primary cardiac tumors are relatively rare; secondary tumors are far more common (20–40 times), occurring in 15% of malignant neoplasms. Of primary cardiac tumors, only 25% are malignant and diagnosis is usually difficult. Echocardiography is the main imaging technique used, although other methods such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and 3D echocardiography provide greater accuracy.2 Scintigraphy also has a role in diagnosis and stratification, as with other forms of cancer.3 A definitive diagnosis always requires histological analysis.2 Clinical presentation may be atypical or may mimic benign etiologies.1

Mesotheliomas are rare and extremely aggressive. They originate in serosa, including the pericardium, and are associated with asbestos exposure through mechanisms that are not fully understood. They respond poorly to currently available treatments, including combined therapy. Unlike other tumors, there is no known early non-metastatic stage. Assessment of biomarkers is thus an important aid in early diagnosis and management. However, the low incidence of these tumors has hindered research into associated molecular defects. Although various potentially useful markers for diagnosis, prognosis and management have been identified, including osteopontin, mesothelin, metalloproteinases, and angiogenetic and growth factors, the literature shows conflicting results and use of these markers in clinical practice is still evolving.4

As would be expected, primary pericardial mesotheliomas are extremely rare (estimated incidence of 0.0022% in a study of 500000 autopsies) but even so they are the most common primary pericardial tumor.5 They can present as a localized or diffuse mass, and three histological types have been described: epithelial, spindle cell and biphasic (epithelial and spindle cells occurring together).6 Unlike pleural mesotheliomas, no consistent link has been found with asbestos exposure, as in the present case.6

Few cases have been reported in the literature and antemortem diagnosis is infrequent.3 It predominantly affects men (3:1), between the fifth and seventh decades of life, although cases have been reported at younger and older ages.7 Clinical presentation can include the whole spectrum of manifestations of pericardial disease, from the mildest to the final stage of constrictive pericarditis.8 Pericardial mesothelioma responds poorly to radiotherapy, and while chemotherapy can reduce the tumor mass, only surgical resection is curative in localized forms.9,10 However, the prognosis is dismal, since clinical presentation is generally late. Median survival is only six months after symptom onset, although pericardiectomy (frequently partial) is palliative in the case of constrictive pericarditis.3

Resection was incomplete in the case presented, and so it was not possible to resolve the patient's hemodynamic instability. The presence of ischemic colitis was interpreted as probably due to poor perfusion, although an embolic event due to the malignancy cannot be excluded.

ConclusionUnlike most cases of pericardial disease, this one demonstrates the unfavorable clinical course of a young patient after an episode of acute pericarditis. The final diagnosis was only arrived at by histological analysis following partial surgical resection and after the patient had died.

There should be stronger suspicion of a malignant cause of pericardial disease if a patient has an unfavorable clinical course that is refractory to therapeutic measures. Even with currently available imaging techniques, only histological analysis can establish a definitive diagnosis, and analysis of pericardial fluid following pericardiocentesis may be inconclusive.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ramos V, et al. Causa rara de doença pericárdica. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2012.05.024.