A diagnosis of congenital heart disease is usually established at an early age, so infective endocarditis is a rare form of presentation.

The authors describe the case of a male adolescent with a week-long history of intermittent fever and unquantified weight loss. Physical examination detected pansystolic and diastolic murmurs, and an associated precordial thrill. Laboratory tests showed evidence of an active infection. Etiological investigation revealed a perimembranous ventricular septal defect, aortic regurgitation, and aortic and mitral valve vegetations. A diagnosis of mitral-aortic infective endocarditis was made and he was started on intravenous antibiotics and anticongestive therapy. After initial clinical improvement, he developed symptoms and signs of congestive heart failure. Repeat echocardiography showed an extensive mitral-aortic paravalvular abscess. The antibiotics were changed and anticongestive therapy was intensified, and he subsequently underwent surgery. The outcome has been generally favorable, and at present he is asymptomatic under anticongestive therapy.

O diagnóstico de cardiopatia congénita é estabelecido habitualmente em idade precoce, logo, a endocardite infecciosa é uma forma de apresentação rara desta patologia.

Descreve-se um caso clínico de um adolescente com febre intermitente com uma semana de evolução e perda ponderal não quantificada. A observação detetou um sopro holossistólico rude e um sopro diastólico, associados a um frémito na região precordial. Analiticamente, apresentava sinais sugestivos de um processo infeccioso ativo. A investigação etiológica revelou a presença de uma comunicação interventricular perimembranosa restritiva, bicuspidia aórtica com regurgitação aórtica e vegetações a nível da válvula mitral e aórtica. Perante o diagnóstico de endocardite mitroaórtica, iniciou antibioterapia endovenosa associada a terapêutica anticongestiva. Após melhoria clínica inicial, desenvolveu quadro de insuficiência cardíaca congestiva. Repetiu o ecocardiograma, que mostrou abcesso paravalvular aórtico e mitral extenso. A antibioterapia foi substituída e a terapêutica anticongestiva foi intensificada. Foi posteriormente submetido a cirurgia cardíaca. A evolução tem sido favorável, mantendo-se assintomático sob terapêutica anticongestiva.

Infective endocarditis (IE) accounts for 0.5–1 of every 1000 hospital admissions (excluding postoperative endocarditis). Around 70% of cases at pediatric ages occur in children with congenital heart disease (CHD),1 especially ventricular septal defect (VSD).2

We present the case of a previously apparently healthy adolescent with a late diagnosis of CHD, in which IE was the first manifestation of the disease.

Case reportWe describe the case of a 12-year-old boy, of Roma ethnicity and adverse socioeconomic status, with no known personal history of disease (there was no record of medical check-ups during childhood) or previous diagnosis of a heart defect. He was brought to the emergency department of his local hospital seven days after the onset of intermittent fever, coughing fits and unquantified weight loss, but no other symptoms. Cardiac auscultation revealed a harsh pansystolic murmur at the left sternal border and a diastolic murmur at the right second intercostal space, together with a precordial thrill. Physical examination showed multiple untreated caries, but no other relevant alterations including signs of congestive heart failure (CHF). Laboratory tests showed an active infection (neutrophilic leukocytosis: 24 103/μl, with 20 × 103/μl neutrophils, and C-reactive protein 5.6 mg/dl). Transthoracic echocardiography with Doppler study was performed via a telemedicine link to our department, which revealed a small perimembranous restrictive VSD, a bicuspid aortic valve without stenosis but with moderate regurgitation (grade III/VI), and aortic and mitral valve vegetations. Left ventricular function was preserved.

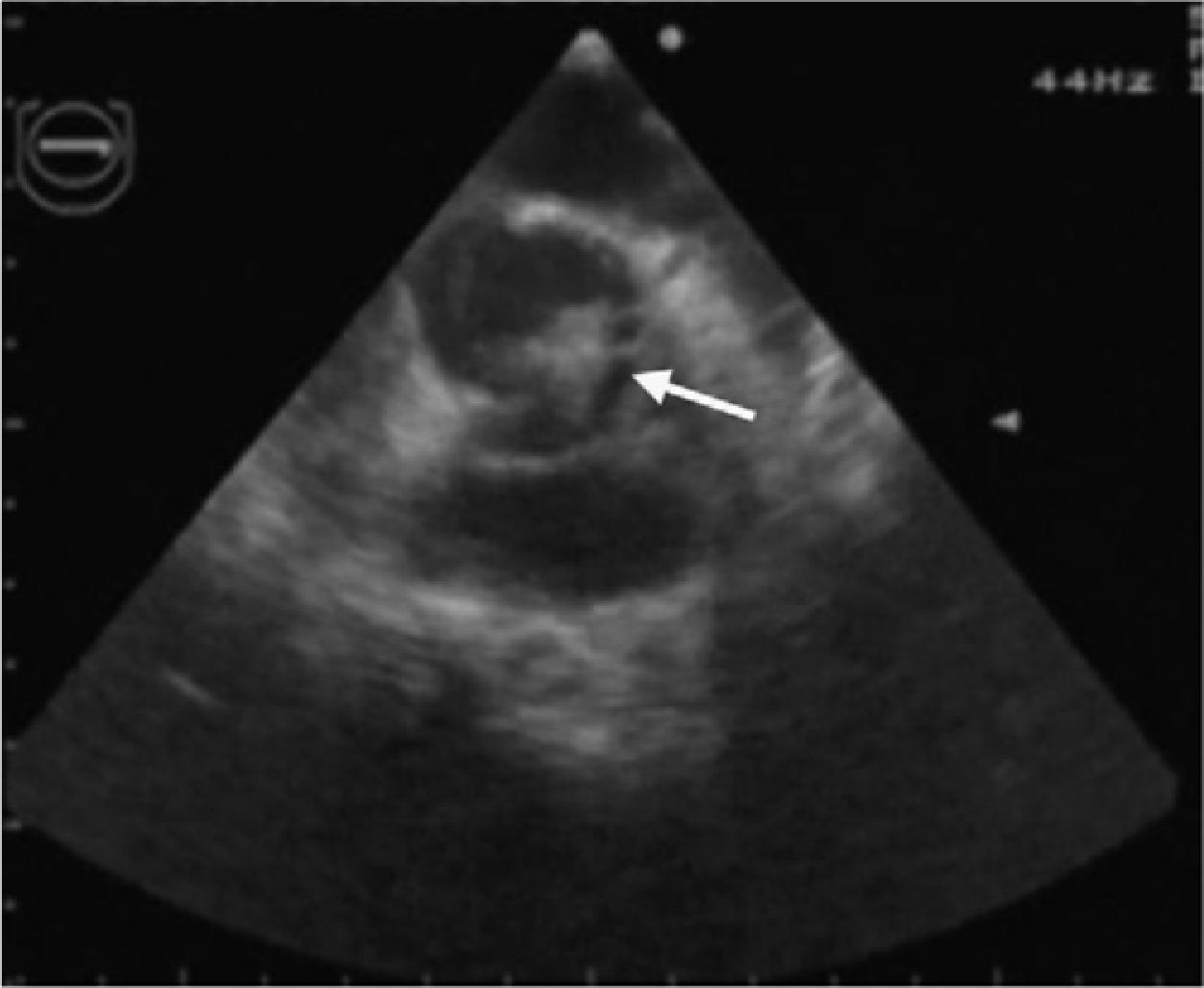

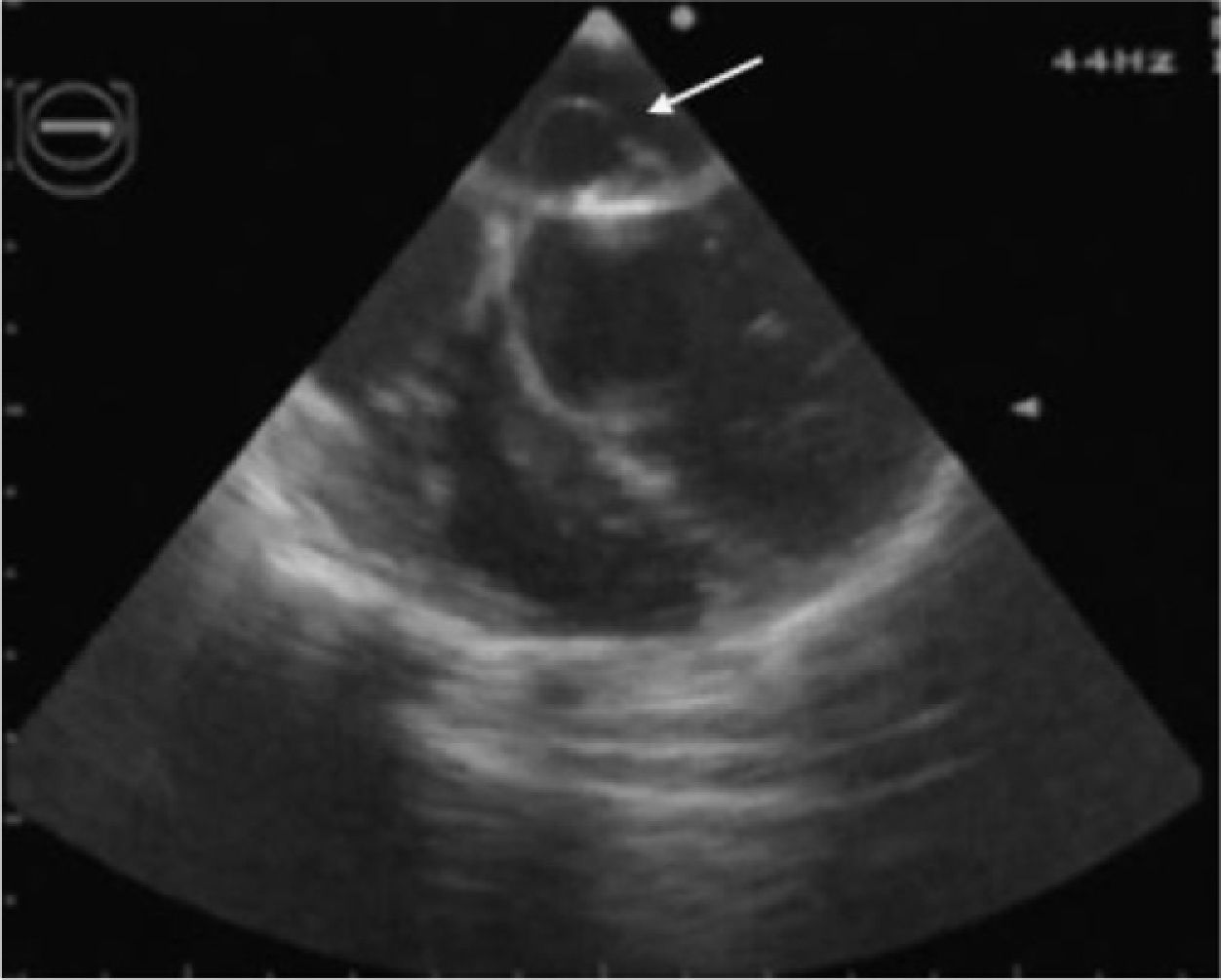

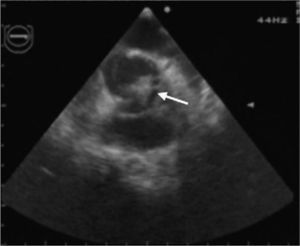

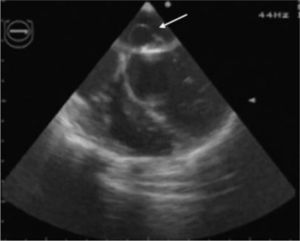

In view of the diagnosis of mitral-aortic infective endocarditis, empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy was begun with vancomycin (30 mg/kg/day) and gentamicin (5 mg/kg/day), together with oral anticongestive therapy with diuretics (furosemide 1 mg/kg and 25 mg spironolactone every 12 hours) and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (captopril 1 mg/kg every eight hours). Streptococcus mitis, susceptible to the antibiotics prescribed, was isolated in blood samples collected before the start of antibiotic therapy. The initial clinical course was favorable, the fever subsiding on the sixth day of treatment. However, fever recurred during the second week of hospital stay, together with signs and symptoms of CHF. The antibiotics were changed to ceftriaxone (60 mg/kg/day) and teicoplanin (10 mg/kg/day), and diuretic therapy was intensified, furosemide being increased to 1 mg/kg every six hours and administered intravenously; the dosage and form of administration of other therapy was unchanged. Cultures of blood samples collected before the change in antibiotics were negative. Transesophageal echocardiography was also performed at this stage, which showed aortic and mitral valve vegetations (Figures 1 and 2), as well as a mitral-aortic paravalvular abscess. Left ventricular function was also mildly impaired. Rifampicin (15 mg/kg/day) was added to the antibiotic regime.

Despite optimized anticongestive therapy, the patient remained clinically unstable and in New York Heart Association functional class II–III/IV with signs of low cardiac output, requiring inotropic support. Four days after this clinical worsening, he was referred to a surgical center where he underwent aortic valve replacement with an aortic homograft, removal of the mitral valve vegetations and reconstruction of the anterior leaflet with a bovine pericardial patch, and direct closure of the VSD. The postoperative period was uneventful and the second antibiotic regime was maintained for a further four weeks after surgery, a total of six weeks (nine days with vancomycin and gentamicin and five weeks with ceftriaxone, teicoplanin and rifampicin).

There was marked echocardiographic improvement during follow-up. At present, three years later, the patient is clinically stable under anticongestive therapy. The last transthoracic echocardiogram showed mild to moderate mitral regurgitation (grade I–II/IV), and normal biventricular function. However, the left atrium (LA) remained dilated (diastolic diameter 41 mm, corresponding to a Z-score of +3.21 and LA/aorta ratio in M-mode Doppler of 1.4), with estimated pulmonary artery pressure of 40–45 mmHg, indicating mild pulmonary hypertension.

DiscussionIE is rare but potentially fatal in pediatric patients. In-hospital mortality is 20%, but is much higher in complicated cases.3

Around 70% of cases at pediatric ages occur in children with CHD,1 although its frequency appears to be rising, due partly to the increasing number of children surviving after surgical correction of complex CHD.4 The association between CHD and IE represents a lifetime risk, as all forms of CHD except ostium secundum atrial septal defect predispose to IE. The defects most commonly involved are tetralogy of Fallot, VSD, aortic valve disease, transposition of the great arteries and systemic-pulmonary shunt.4

The boy in the case presented had a VSD and bicuspid aortic valve, both previously undiagnosed. In one published series, the incidence of IE in children with VSD was 1–2.4 per 1000.5

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causal agent in acute IE in developed countries. Infection by viridans group or alpha-hemolytic streptococci (which includes S. mitis) is also common, particularly in children with dental disease, leading to subacute disease,6 as in the case presented. More recently, there has been a marked increase in the incidence of IE caused by fungi or microorganisms of the HACEK group (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella and Kingella) in newborns and immunocompromised patients.4

There are two important factors in the pathogenesis of IE: an area of endothelial damage and the presence of bacteremia, even if transient. Patients have some form of underlying hemodynamic abnormality, such as a pressure gradient or turbulent flow between two cardiac chambers or the great vessels.7 These changes damage the endothelium, which can be directly invaded by virulent microorganisms or induce thrombus formation and subsequent bacterial adhesion, leading to the development of vegetations. As in our patient, one cause of transient bacteremia is poor oral hygiene and untreated dental caries, whether or not dental procedures are performed.

The modified Duke criteria are now the most widely used to diagnosis IE, and are based on the patient's medical history, physical examination and complementary diagnostic exams, including two or more blood cultures positive for the microorganisms typical of IE and echocardiographic evidence of endocardial involvement.8

Initial empirical treatment is an antistaphylococcal penicillin together with an aminoglycoside, effective against the most common microorganisms (S. viridans, S. aureus and Gram-negative bacteria). The final choice of antibiotic therapy is guided by the results of susceptibility tests. Treatment duration depends on the etiological agent isolated, but on average ranges between four and eight weeks of intravenous antibiotics. This prolonged regime is essential to ensure that bactericide concentrations reach levels effective against microorganisms with low metabolic rates in vegetations that are protected from phagocytic activity.

Surgery plays a crucial role in more severe cases, notably when there is CHF refractory to medical therapy or secondary to valve dysfunction, perivalvular abscess or vegetations larger than 1 cm, and infection by fungi or Pseudomonas.4 Traditionally, the accepted dogma was to avoid surgery during the active phase of the disease due to tissue friability, which made surgery difficult and led to high postoperative mortality and risk of valve dysfunction. This idea has now been abandoned and early surgery is now recommended.9

Our patient was transferred to a surgical center after clinical worsening secondary to various complications that are criteria for urgent surgery (within a few days).10 The indications for urgent surgery include: (1) CHF with impaired left ventricular function (class I recommendation, level of evidence B); (2) locally uncontrolled infection, with aortic paravalvular abscess (class I recommendation, level of evidence B) and persisting fever (class I recommendation, level of evidence B); and (3) prevention of systemic embolism associated with large aortic and/or mitral vegetations (class I recommendation, level of evidence C).10

The initial surgical option was for a Ross procedure, but the aortic valve had to be replaced with an aortic homograft since the aortic abscess extended anteriorly up to the pulmonary artery wall, making it friable, and hence the pulmonary valve could not be used in aortic position.

Finally, prevention of IE is as important as diagnosis and treatment, for which good oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups are essential. The latest guidelines recommend a more rational use of prophylactic antibiotic therapy prior to interventional procedures, limiting their use to patients with predisposing cardiac conditions.8

ConclusionIE at pediatric ages is generally associated with CHD. Diagnosis is based on symptoms, together with new echocardiographic alterations and blood cultures positive for typical microorganisms.

Antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone of treatment, and should last for four to eight weeks and be administered intravenously. However, the most important measure is prevention, based on good oral hygiene and antibiotic prophylaxis prior to high-risk invasive procedures.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vaz Silva P, et al. Endocardite infecciosa como primeira manifestação de cardiopatia congénita de apresentação tardia. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2012.05.023.