Renal insufficiency, as evidenced by an increase in creatinine, is associated with higher mortality in patients with acute heart failure (AHF). Conversely, hemoconcentration (HC) in AHF is associated with lower mortality, but can also cause an increase in creatinine. Our aim was to assess the prognosis of HC in patients hospitalized for AHF presenting with or without worsening renal function (WRF).

MethodsA total of 618 consecutive patients admitted for AHF were included. WRF was defined according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria and HC was defined as an elevation of hemoglobin during hospitalization compared to the admission value. Six-month all-cause mortality was analyzed.

ResultsThe patients’ mean age was 79±11 years; 58% were women. Mortality at six months was 38% and 49% of patients had WRF. HC occurred in 38.9% of patients with WRF and was associated with improved survival (HR 1.6, 95% CI 1.10-2.34; p=0.02) compared to WRF without HC. HC was associated with better survival in KDIGO stages 1 and 2 (HR 1.8; 95% CI 1.1-2.8; p=0.01). For patients without chronic kidney disease (CKD) with WRF in stages 1 and 2, HC was associated with significantly better survival (HR 2.3; 95% CI 1.2-4.2; p=0.01).

ConclusionIn patients admitted for AHF without renal failure or CKD, WRF with HC is associated with a better prognosis, similar to that of patients without WRF, and should therefore be reclassified as ‘pseudo-WRF’.

Alterações na função renal com aumento da creatinina têm sido associadas a maior mortalidade em doentes com insuficiência cardíaca aguda (ICA). Já a hemoconcentração na ICA tem-se associado a redução da mortalidade, é também uma causa de elevação da creatinina. Avaliar o prognóstico da hemoconcentração (HC) em doentes hospitalizados por ICA com e sem agravamento da função renal (AFR).

MétodosAnalisados 618 doentes consecutivos admitidos por ICA. Definido agravamento da função renal de acordo com os critérios KDIGO e HC como elevação da hemoglobina durante a hospitalização comparativamente à admissão. Avaliada morte por qualquer causa aos seis meses.

ResultadosA idade média foi 79 ± 11 anos; 58% mulheres. A mortalidade aos seis meses foi de 38%; 49% dos doentes tiveram AFR. HC ocorreu em 38,9% dos doentes com AFR e associou-se a maior sobrevivência após ajuste de fatores demográficos e comorbilidades (HR 1,6; IC95%: 1,06–2,33; p=0,026), comparativamente a AFR sem HC. Na avaliação por estádios KDIGO, HC associou-se a maior sobrevivência nos estádios 1 e 2 (HR 1,8; IC95%: 1,1–2,8; p=0,01). Nos doentes com doença renal crónica (DRC) com AFR nos estádios 1 e 2, a HC esteve associada a maior sobrevivência (HR 2,3, IC95%: 1,2-4,2, p=0,01).

ConclusãoEm doentes admitidos por ICA sem falência renal ou DRC, o AFR com HC está associada a bom prognóstico. O seu prognóstico é similar a doentes sem AFR e deverá assim ser reclassificado como «pseudo-AFR».

Heart failure is a chronic systemic disease, the symptoms and natural history of which are related to neurohormonal dysregulation impacting water and sodium retention.1 Kidney disease is one of the most important comorbidities and its presence is a powerful predictor of poor outcomes in patients with heart failure.1 Only 9% of the 118465 patients admitted with acute heart failure (AHF) in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) had normal renal function (defined as glomerular filtration rate [GFR] ≥90 ml/min/1.73 m2).2

Worsening renal function (WRF) occurs in 30-50% of patients admitted with heart failure, depending on the definition used. It is associated with higher rehospitalization rates, increased length of hospital stay, higher mortality (with one-year mortality around 30%), and greater health costs.3–5

Historically, impairment of renal function has been attributed to low cardiac output and resulting renal hypoperfusion.6,7 Nevertheless, there is growing evidence that other factors, such as tubular structural damage, systemic venous congestion and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, are strongly associated with WFR.6–13

It has been suggested that AHF patients with mild creatinine elevation but without established renal failure have a better prognosis, since these changes are due to hemoconcentration (HC) rather than to true WRF.14–18

Our aim was to assess HC in patients hospitalized for AHF presenting with or without WRF and to determine its prognostic value.

MethodsStudy designThis was a single-center retrospective study of patients admitted for AHF. Clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic data were collected.

The protocol was approved by the head of our institution's cardiology department and the ethics committee in March 2014, in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and national regulations.

Patients and eligibility criteriaWe enrolled 618 consecutive patients admitted to our cardiology department for AHF between January 1 and December 31, 2012.

AHF was defined as the rapid onset of symptoms and signs secondary to abnormal cardiac function and the presence of objective evidence of a structural or functional abnormality of the heart at rest (cardiomegaly, third heart sound, cardiac murmur, echocardiographic abnormality or elevated natriuretic peptides). These diagnostic criteria were in accordance with the 2016 European Society of Cardiology heart failure guidelines.7

Patients were excluded if they met the following criteria: absence of creatinine measurement during the first two days of hospitalization, hospital stay ≤48 hours, or end-stage renal disease on dialysis.

Initial data collectionAn extensive review of clinical records from outpatient clinics, hospital wards and emergency department admissions was performed by two co-investigators. The following data were collected: demographics, previous medical history (including smoking, diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease [CKD] and previous AHF), physical examination (signs and symptoms of AHF, blood pressure, heart rate), etiology and triggers of AHF, laboratory values (including baseline serum urea and creatinine levels; hemoglobin and hematocrit at admission; admission and discharge levels of urea, creatinine, sodium and potassium), medications administered during hospitalization for AHF (including furosemide doses), length of hospital stay, and date of death.

Baseline creatinine was defined as a value measured within three months of admission. When this value was not available, it was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation according to the recommendations of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Working Group.19

Baseline estimated GFR (eGFR) was calculated based on the MDRD study equation, using the baseline creatinine value.

Change in renal function was calculated as the absolute difference between creatinine at admission and repeat value measured 48-72 hours following admission. WRF was defined as an increase in creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dl and was classified according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria (Table 1).20 For our classification, only serum creatinine was taken in account, since urine output values were difficult to collect.

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes classification of acute kidney injury.

| Stage | Serum creatinine |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5-1.9 times baseline or ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥265 μmol/l) increase |

| 2 | 2.0-2.9 times baseline |

| 3 | 3.0 times baseline or increase in serum creatinine to ≥4 mg/dl (≥353.6 μmol/l) or initiation of renal replacement therapy or in patients <18 years, decrease in eGFR to <35 ml/min/1.73 m2 |

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

HC was defined as an increase in hemoglobin during hospital stay. When there was WRF at admission (compared to baseline creatinine), hemoglobin variation was calculated by subtracting hemoglobin at discharge from hemoglobin at admission; when there was no WRF at admission, hemoglobin variation was calculated by subtracting hemoglobin on the day of peak creatinine value from hemoglobin at admission.

The furosemide dose was converted to furosemide equivalents, with 40 mg of oral furosemide corresponding to 20 mg of intravenous furosemide. Mean daily loop diuretic doses were calculated by dividing the total dose (in furosemide equivalents) used during hospital stay by the length of hospital stay (in days).

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography during the index hospitalization or within six months of admission.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]), and categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage. Survival curves were plotted and stratified using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to test for differences between survival curves. A Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS for Windows, version 21.

ResultsStudy populationThe baseline characteristics of the 618 patients enrolled in the study are summarized in Table 2. Their mean age was 79±11 years, 358 (58%) were women, 60% had hypertension, 27.7% dyslipidemia, 36.2% diabetes and 20.5% previous ischemic heart disease. The most frequent etiology of heart failure was ischemic heart disease (20.5%), followed by valvular disease (10%) and hypertensive cardiomyopathy (9.7%). The most common trigger of AHF was respiratory infection (40%), followed by myocardial infarction (7.8%) and arrhythmias (7.8%). Overall, 67% of patients were medicated prior to hospital admission with loop diuretics, 65% with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, 32.4% with beta-blockers, 15.9% with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and 12% with digoxin. The median length of hospital stay was seven (IQR: 3-12) days. WRF occurred in 49% of patients; when stratified according to the KDIGO classification, 56% of them were in stage 1, 28% in stage 2 and 17% in stage 3. Notably, patients with WRF during hospital stay were older (81±8.8 vs. 78.1±12 years, p<0.001) and had longer hospital stay (eight vs. seven days; p=0.03), with no difference in the mean dose of diuretic used (59 vs. 60 furosemide equivalents; p=0.6). HC occurred in 38.9% of patients with WRF and in 47.3% of patients without WRF. During six-month follow-up, 38% (n=235) of patients died.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population stratified by serum creatinine levels at admission.

| Total | WRF (n=303) | No WRF (n=315) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 79±11 | 81±8.8 | 78.1±12 | <0.001 |

| Female | 58.1% | 60.1% | 56.2% | 0.33 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 60.7% | 61.1% | 60.3% | 0.85 |

| Dyslipidemia | 27.7% | 24.8% | 30.5% | 0.11 |

| Diabetes | 36.2% | 39.6% | 34.3% | 0.17 |

| CAD | 20.5% | 20.5% | 20.6% | 0.97 |

| Smoking | 4.5% | 2.6% | 6.3% | 0.03 |

| COPD | 21.2% | 21.1% | 21.3% | 0.96 |

| CKD | 22.5% | 30.7% | 14.6% | <0.01 |

| Stroke | 9.5% | 8.9% | 10.2% | 0.60 |

| Dementia | 5.8% | 4.6% | 7% | 0.21 |

| Cirrhosis | 1.5% | 1% | 1.9% | 0.34 |

| Malignancy | 11.5% | 12.5% | 10.5% | 0.42 |

| Vital signs | ||||

| Heart rate | 91±25 | 91±26 | 90±25 | 0.96 |

| SBP | 135±32 | 133±32 | 137±31 | 0.09 |

| DBP | 72±19 | 71±20 | 74±19 | 0.05 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF | 43±14 | 42±15 | 44±13 | 0.36 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| Troponin I | 0 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.09) | 0 (0.06) | 0.08 |

| Pro-BNP | 4171 (8805) | 6714 (10971) | 2795 (5992) | <0.001 |

| Admission serum sodium | 137 (6) | 137 (5.4) | 136 (6) | 0.27 |

| Admission potassium | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.9) | 0.03 |

| Discharge serum sodium | 138 (6) | 138 (6.4) | 137 (5.6) | 0.14 |

| Discharge potassium | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.7) | 0.01 |

| ASP | 30 (24) | 31 (27) | 30 (23) | 0.43 |

| ALT | 41 (27) | 40 (30) | 41 (25) | 0.94 |

| ALP | 113 (65) | 120 (74) | 111 (53) | 0.06 |

| TC | 161 (59) | 151 (61) | 165 (59) | 0.10 |

| CRP | 2.6 (6.6) | 2.8 (6.8) | 2.3 (6.4) | 0.11 |

| Baseline urea | 45.7 (44) | 47.5 (47.8) | 43.2 (40.6) | 0.73 |

| Baseline creatinine | 1 .01 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1.02 (0.44) | 0.17 |

| Admission urea | 67 (55) | 88 (71) | 55 (34.5) | <0.001 |

| Admission creatinine | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Admission hemoglobin | 12.2 (3) | 11.9 (2.8) | 12.5 (2.9) | 0.003 |

| Hematocrit | 38 (9) | 37 (8.5) | 38.9 (9.1) | 0.003 |

| HC | 43.2% | 38.9% | 47.3% | 0.036 |

| Length of hospital stay | 7 (9) | 8 (9) | 7 (8) | 0.03 |

| Furosemide equivalent (mg/day) | 60 (41) | 59 (40) | 60 (42) | 0.56 |

| WRF day | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| KDIGO classification | ||||

| Stage 1 | 56% | |||

| Stage 2 | 28% | |||

| Stage 3 | 17% | |||

| Prior treatment | ||||

| ACEIs/ARBs | 65% | 67% | 63.2% | 0.32 |

| Beta-blockers | 32.4% | 34% | 30.8% | 0.40 |

| CCBs | 25.2% | 28.1% | 22.5% | 0.12 |

| Loop diuretics | 66.7% | 70.6% | 62.9% | 0.04 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 12.1% | 14.5% | 9.8% | 0.08 |

| MRAs | 15.9% | 18.2% | 13.7% | 0.13 |

| Digoxin | 11.7% | 7.9% | 15.2% | <0.01 |

| Nitrates | 15.5% | 17.2% | 14% | 0.27 |

| Statins | 37.2% | 38.6% | 35.9% | 0.48 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 17.5% | 20.8% | 14.3% | 0.03 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 43% | 45.2% | 41% | 0.29 |

| Oral anticoagulants | 13.9% | 13.2% | 14.6% | 0.62 |

| Oral antidiabetics | 20.6% | 20.5% | 20.6% | 0.96 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Coronary disease | 19.4% | 19.5% | 19.4% | 0.98 |

| Cor pulmonale | 5% | 5% | 5.1% | 0.94 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 4.9% | 3.6% | 6.1% | 0.15 |

| HCM | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.97 |

| Hypertensive cardiomyopathy | 9.7% | 8.9% | 10.5% | 0.42 |

| Arrhythmia | 4.1% | 3.6% | 4.5% | 0.91 |

| Valvular heart disease | 10% | 10.9% | 9.2% | 0.48 |

| Unknown | 46.2% | 47.9% | 44.6% | 0.44 |

| Triggering factors | ||||

| Respiratory infection | 40% | 37.4% | 42.5% | 0.21 |

| Infection (not respiratory) | 5.7% | 6.6% | 4.8% | 0.32 |

| Anemia | 3.7% | 4.3% | 3.2% | 0.46 |

| MI | 7.8% | 6% | 9.6% | 0.10 |

| Therapeutic compliance | 4.9% | 4.6% | 5.1% | 0.79 |

| Arrhythmia | 7.8% | 8.6% | 7% | 0.46 |

| Valvular disease | 2.1% | 3% | 1.3% | 0.14 |

| Hypertensive crisis | 3.9% | 4.6% | 3.2 | 0.35 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.5% | 1% | 0% | 0.08 |

| Unknown | 23.6% | 23.9% | 23.3% | 0.91 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) according to normality unless otherwise specified; categorical variables are presented as percentages.

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine transaminase; ARBs: angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASP: aspartate transaminase; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCBs: calcium channel blockers; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HC: hemoconcentration; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; KDIGO: Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MRAs: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; MI: myocardial infarction; Pro-BNP: pro-brain natriuretic peptide; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; WRF: worsening renal function.

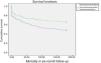

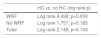

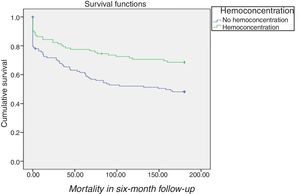

Patients without WRF during hospital stay had better survival than those with WRF (log rank p=0.001) (Figure 1).

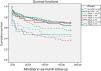

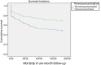

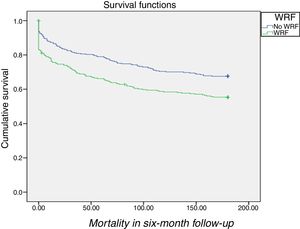

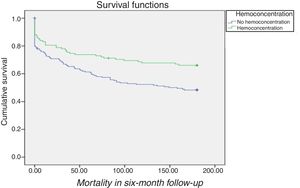

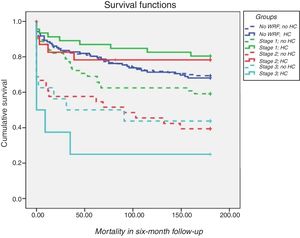

Prognostic value of hemoconcentrationIn patients with WRF, HC was associated with improved survival after adjustment for demographics and comorbidities (hazard ratio [HR] 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10-2.34; p=0.02) compared to those without HC (Table 3 and Figure 2). In terms of KDIGO staging, HC was associated with increased survival in stages 1 and 2 after adjustment for age, gender, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, CKD, admission hemoglobin, admission creatinine and admission serum sodium (HR 1.76; 95% CI 1.12-2.76; p=0.01), with no significant difference for patients at stage 3 (log rank p=0.7) (Figure 3). Patients with HC and WRF in stages 1 and 2 had similar outcomes to those without WRF, regardless of the presence of HC during hospital stay (log rank p=0.01) (Figure 4).

For patients without CKD with WRF in stages 1 and 2, HC was associated with significantly better survival both before (HR 2.8; 95% CI 1.5-5.1; p=0.001) and after adjustment for baseline characteristics (HR 2.3; 95% CI 1.2-4.2; p=0.01) (Figure 5) which, interestingly, did not differ significantly among CKD patients (log rank p=0.4) (Table 4).

Prognostic value of hemoconcentration for mortality according to baseline renal function.

| With CKD (log rank p) | Without CKD (log rank p) | |

|---|---|---|

| No WRF and HC | Log rank p=0.14 | Log rank p=0.71 |

| WRF stage 1 and 2 and HC | Log rank p=0.43 | Log rank p<0.0001; HR 2.26; 95% CI 1.20-4.24; p=0.01 |

| WRF stage 3 and HC | Log rank p=0.35 | Log rank p=0.34 |

CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HC: hemoconcentration; HR: hazard ratio; WRF: worsening renal function.

Our findings show that among patients hospitalized for AHF with WRF and without renal failure (stage 3) or CKD, HC is associated with a better prognosis, similar to patients without WRF. Thus, HC is a protective response to anticongestive therapy and an increase in creatinine in this setting is not associated with a worse prognosis, as opposed to the poorer prognosis that corresponds to an increase in creatinine due to acute kidney injury.

This study extends and corroborates the results obtained in previous studies by confirming a positive association between HC and WRF.15,21

The pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for cardiorenal syndrome are complex and multifactorial, and are not fully understood.22,23

Intuitively, hemodynamic dysregulation is the pathophysiological basis. Decreased cardiac output and fluid redistribution lead to decreased renal perfusion and to compensatory stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. In the long term, these changes induce adverse effects on the heart and kidney by promoting fibrosis, apoptosis and ventricular remodeling.22,24

However, there is evidence that renal hypoperfusion is not the major pathophysiological basis for cardiorenal syndrome, as the proportion of patients with hypotension at admission is relatively small in large registries.2,25 This is corroborated by Mullens et al., who reported that patients who developed WRF did not have a lower cardiac index at admission than those without WRF.9

Isolated temporary elevation of central venous pressure (CVP) is associated with decreased renal perfusion and GFR. Winton, for example, observed that diuresis by an isolated canine kidney was markedly reduced at a renal venous pressure of 20 mmHg and was abolished at pressures >25 mmHg.26 In addition, an early experiment in normal individuals concluded that producing an intra-abdominal pressure of 20 mmHg with abdominal compression markedly reduced GFR.27 However, this evidence has not been consistent, with CVP proving to be an independent predictor of WRF, particularly in low cardiac output situations.28–30

Elevation of cytokines and other inflammatory markers has been reported in patients with AHF. It has been proposed that inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor play a role in sodium retention, myocardial dysfunction, acute renal dysfunction, and vascular injury.31 Colombo et al. showed that in normal individuals, peripheral venous congestion triggers the release of inflammatory mediators and the activation of endothelial cells.32

The response to anticongestive therapy in patients with AHF varies dramatically. In some patients, diuretics can lead to intravascular volume depletion, reduction of renal perfusion and deterioration of renal function. In others, it can decrease venous congestion and therefore improve GFR.14–16,33,34

In the Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial, transient WRF with the use of high-dose diuretics was associated with early clinical improvement and was not associated with a worse prognosis at 60 days.34 In 599 consecutive patients with AHF, Metra et al. found that the prognostic value of WRF was mainly determined by the presence of congestion; in the absence of congestion, increases in serum creatinine levels had no prognostic value. By contrast, WRF was strongly associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes in patients with persistent congestion.14 Similarly, in an analysis of the ESCAPE trial, Testani et al. showed that HC was associated with both renal impairment and better outcomes.15

These studies are in line with our finding that in patients hospitalized for AHF, the clinical impact of changes in creatinine is largely determined by baseline renal function and by response to anticongestive therapy. In our study, in contrast to Breidthardt et al.,21 HC was prognostic only in WRF patients and had no prognostic value in patients without WRF.

The main conclusion of our study was that HC as a surrogate for anticongestive therapy had prognostic value in patients without CKD but with elevated creatinine. According to our results, it is essential to measure baseline renal function when interpreting renal function in patients with AHF. When creatinine elevation occurs with CKD prior to hospitalization, special care should be taken when treating these patients. Nevertheless, in patients without renal impairment, a slight to moderate increase in creatinine when accompanied by HC may merely represent effective diuresis, and an increase in serum creatinine accompanied by improvement of heart failure signs and symptoms does not appear to be associated with a poor prognosis.

These results suggest that it may be a mistake to assume that an elevation of creatinine alone means that the patient has acute kidney injury. Acute kidney injury indicates that renal injury has occurred, which may or may not be reversible. However, in our study, WRF associated with HC and without renal failure or CKD correlated with increased survival, similar to patients without WRF, suggesting that this kind of WRF should be reclassified as ‘pseudo-WRF’.

Our results highlight the importance of assessing changes in creatinine compared to baseline renal function in patients with AHF.

LimitationsOur study has several limitations. Our data were collected and analyzed retrospectively, so baseline serum creatinine and LVEF measurements were not available for all patients. Treatments at discharge were not assessed, so the effect of pharmacological treatment on prognosis could not be assessed with this design. We describe the results of a single-center study with a limited number of enrolled patients. A larger sample from other centers would better assess the prognostic value of HC and WRF in AHF patients and would validate our results.

ConclusionIn patients admitted for AHF without renal failure or CKD, WRF with HC is associated with a better prognosis, similar to the prognosis of patients without WRF. This should therefore be reclassified as ‘pseudo-WRF’. Our findings suggest that it is not the increase in creatinine that determines prognosis, but rather the clinical context in which the increase in creatinine occurs. Future studies are required to obtain further insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms of AHF and to seek ways to improve the diagnostic and prognostic accuracy of current methods, as well as to explore effective treatments.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.