The incidence of device infection has increased over time and is associated with increased mortality in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs). Gentamicin-impregnated collagen sponges (GICSs) are useful in preventing surgical site infection (SSI) in cardiac surgery. Nevertheless, to date, there is no evidence concerning their use in CIED procedures. Our study aims to determine the effectiveness of treatment with GICSs in preventing CIED infection.

MethodsA total of 2986 adult patients who received CIEDs between 2010 and 2020 were included. Before device implantation, all patients received routine periprocedural systemic antibiotic prophylaxis. The study endpoints were the CIED infection rate at one year and the effectiveness of the use of GICSs in reducing CIED infection.

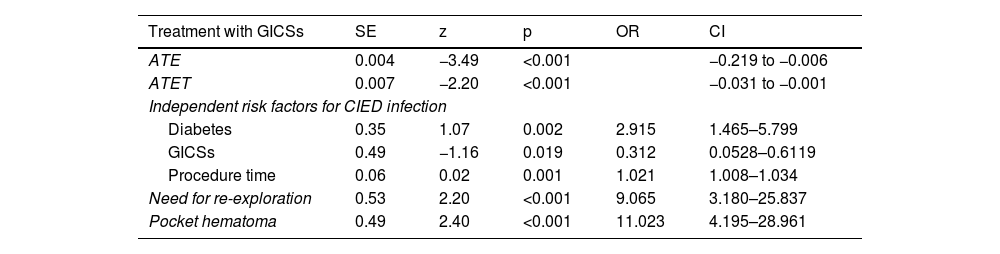

ResultsAmong 1524 pacemaker, 942 ICD and 520 CRT implantations, CIED infection occurred in 36 patients (1.2%). Early reintervention (OR 9 [95% CI 3.180–25.837], p<0.001), pocket hematoma (OR 11 [95% CI 4.195–28.961], p<0.001), diabetes (OR 2.9 [95% CI 1.465–5.799], p=0.002) and prolonged procedural time (OR 1.02 [95% CI 1.008–1.034], p=0.001) were independent risk factors for CIED infection. Treatment with GICSs reduced CIED infections significantly ([95% CI −0.031 to −0.001], p<0.001).

ConclusionsThe use of GICSs may help in reducing infections associated with CIED implantation.

A incidência de infeções em dispositivos está a aumentar e está associada ao aumento da mortalidade em doentes com dispositivos cardíacos eletrónicos implantáveis. As esponjas de colagénio impregnadas com gentamicina (ECIG) são úteis na prevenção de infeções de locais cirúrgicos em cirurgia cardíaca. No entanto, até à data, não existem provas da sua utilização em procedimentos dos dispositivos cardíacos. O nosso estudo visa testar a eficácia do tratamento com ECIG na prevenção de infeções em dispositivos cardíacos.

MétodosIncluímos 2986 doentes adultos submetidos a implantação de dispositivos cardíacos de 2010 a 2020. Antes do implante do dispositivo, todos os pacientes recebiam profilaxia sistémica de rotina periprocedimento com antibióticos. O objetivo principal foi a taxa de infeções em dispositivos cardíacos em um ano e a eficácia da utilização de ECGI na redução das infeções por dispositivos cardíacos.

ResultadosEntre 1524 implantações de pacemaker, 942 desfibrilhadores e 520 CRT, a infeção por DCEI ocorreu em 36 doentes (1,2%). Necessidade de reintervenção precoce (OR 9 [95% CI 3,180-25,837], p<0,001), hematoma da loca (OR 11 [95% CI 4,195-28,961], p<0,001), diabetes (OR 2,9 [95% CI 1,465-5,799], p=0,002) e tempo de procedimento prolongado (OR 1,02 [95% CI 1,008-1,034], p=0,001) foram fatores de risco independentes de infeção em dispositivos cardíacos. O tratamento com ECGI reduziu significativamente as infeções em dispositivos cardíacos ([95% CI −0,031 −0,001], p<0,001).

ConclusõesA utilização de esponjas de colagénio impregnadas com gentamicina pode ajudar a reduzir as infeções associadas à implantação de dispositivos eletrónicos cardíacos.

Implantation of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) has increased significantly over the past decade due to expanded indications for their use in primary prevention and increasingly effective diagnostic pathways for identifying patients eligible for these devices. As a result, there has been a dramatic growth in CIED infections.1 Among CIED procedures, approximately 1–2% of CIED implantations are associated with an infection.2 Dealing with device infection is particularly challenging, as it may involve hospitalizations, prolonged antibiotic therapy, and device removal. Device infection is also associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, and increased healthcare costs worldwide.3–9 In addition to the standard use of antibiotic prophylaxis, various measures can be taken to prevent CIED infection. Recently, absorbable antibacterial envelopes have been developed which can reduce the risk of major CIED infection by 40% without increased risk of complications.3 Although it is effective, the costs of this and other similar treatments are high and their availability is often limited.

Gentamicin-impregnated collagen sponges (GICSs) contain a broad-spectrum antibiotic impregnated in a bovine collagen matrix. GICSs have proved effective in reducing sternal wound infections in cardiac surgery.10 Nevertheless, to date there is no clear evidence on their use in CIED procedures, particularly in patients with predisposing factors for infection that are widely described in the literature.2,4 Our study aims to determine the effectiveness of treatment with GICSs in preventing CIED infection.

MethodsWe retrospectively enrolled 2986 adult patients who underwent CIED implantation in the cardiology department of Policlinico Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy, between 2010 and 2020. All patients provided consent in their medical records to the disclosure of data in anonymous form for research purposes. Inclusion criteria were the following: age >18 years, completion of one-year follow-up, absence of active infection or active inflammatory disease, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class I–III.

The diagnosis of CIED pocket infection was made in accordance with the guidelines of the European Heart Rhythm Association, which establish the diagnosis of definite CIED pocket/generator infection in the presence of generator pocket swelling, erythema, warmth, pain, and purulent discharge/sinus formation, or deformation of the pocket, adherence and threatened erosion, or exposed generator or proximal leads.11 In addition, purulent drainage from the incision combined with clinical and/or laboratory evidence requiring reintervention or hospitalization, together with the presence of vegetation on imaging tests, were considered to indicate a definite infection.

Before device implantation, all patients received periprocedural systemic antibiotic prophylaxis with intravenous administration of first-generation cephalosporins such as cefazolin (1–2 g) or flucloxacillin (1–2 g). Vancomycin (15 mg/kg) was used in the presence of allergy to cephalosporins and since it must be administered slowly (over approximately 1 h), administration started 90–120 min before the incision.11 GICSs were implanted according to the preference of the operator involved. Four physicians were involved in the selection and use of the GICSs.

Data collectionThe following demographic and clinical parameters were collected at baseline: date of birth, gender, clinical and medication history, body mass index (BMI), cardiovascular risk factors, and current conditions including hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic kidney disease, defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg, or self-reported use of antihypertensive medication. Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol >240 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >160 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dl, or self-reported use of lipid-lowering drugs. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose >126 mg/dl or self-reported treatment with hypoglycemic medication. Smokers were defined as individuals who currently or previously smoked. Former smokers were defined as individuals who smoked at least 50 cigarettes in their lifetime but had not smoked in the last year. Obesity was defined as BMI >30 kg/m2. COPD was defined as the presence of chronic bronchitis or emphysema that could lead to the development of airway obstruction. CAD was defined as evidence from imaging modalities or invasive coronary angiography of atherosclerotic disease regardless of significance, or previous percutaneous coronary intervention.

Procedural detailsWe included in our analysis patients who underwent implantation of pacemakers (single and dual-chamber), implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) (single and dual-chamber), and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices (CRT), and elective replacement of device generators. CIED implantation was performed using one of two vascular approaches, through the right or left subclavian vein, or through the left or right cephalic vein. Some patients underwent reintervention during the same hospital stay (e.g., due to need for lead repositioning).

Clinical follow-upA systematic outpatient follow-up was performed at one week (surgical wound inspection), one month, six months, and one year after implantation. The following parameters were assessed: device function, status of the surgical implantation site, and the patient's clinical condition. We considered as having CIED infection those with local signs of inflammation, characterized by erythema, warmth, and purulent discharge. Pocket deformation, adherence, or threat of erosion were considered signs of infection. Similarly, exposed generators or leads were considered to be direct signs of infection regardless of microbiology findings, as recommended by recent guidelines. Pocket hematoma was not considered to be surgical site infection (SSI) and was differentiated from infection by the absence of any evidence from the patient's blood tests, radiological examinations, or clinical symptoms. Hematoma was considered a risk factor, and therefore analyzed among the confounding covariates of the propensity score.

Study endpointsThe study endpoints were the CIED infection rate at one year and the effectiveness of the use of GICSs in reducing CIED infection.

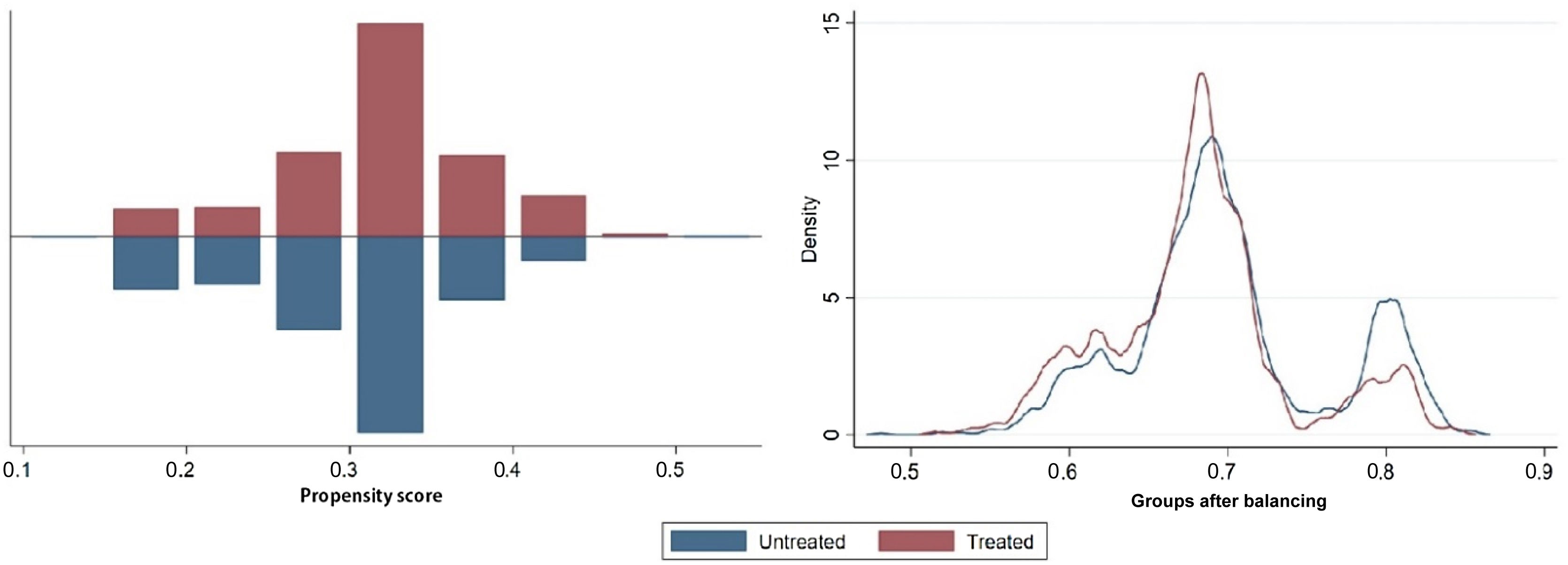

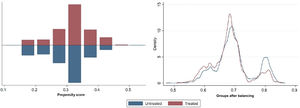

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and STATA statistical software, version 16.0 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) when they did not show a normal distribution. Categorical variables were presented as absolute number (percentage). Two independent sample tests for continuous variables were performed using the Student's t test or the Mann–Whitney test. Propensity score estimation was performed using the pscore package for STATA. Various propensity score estimation models were tested, in particular logistic regression, random forests, classification trees and fixed-effects models. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to assess the balance after propensity score matching. An SMD greater than 0.1 was considered a sign of imbalance. After propensity score matching, the covariates were all balanced (Figure 1).

The effectiveness of GICSs was examined using the t-effect test and the psmatch package for STATA. Finally, conditional logistic regression was performed based on the weights of the covariates after matching to identify predictors of CIED infection, validated by bootstrapping to 100 samples of the original data. A p-value <0.05, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), was considered statistically significant.

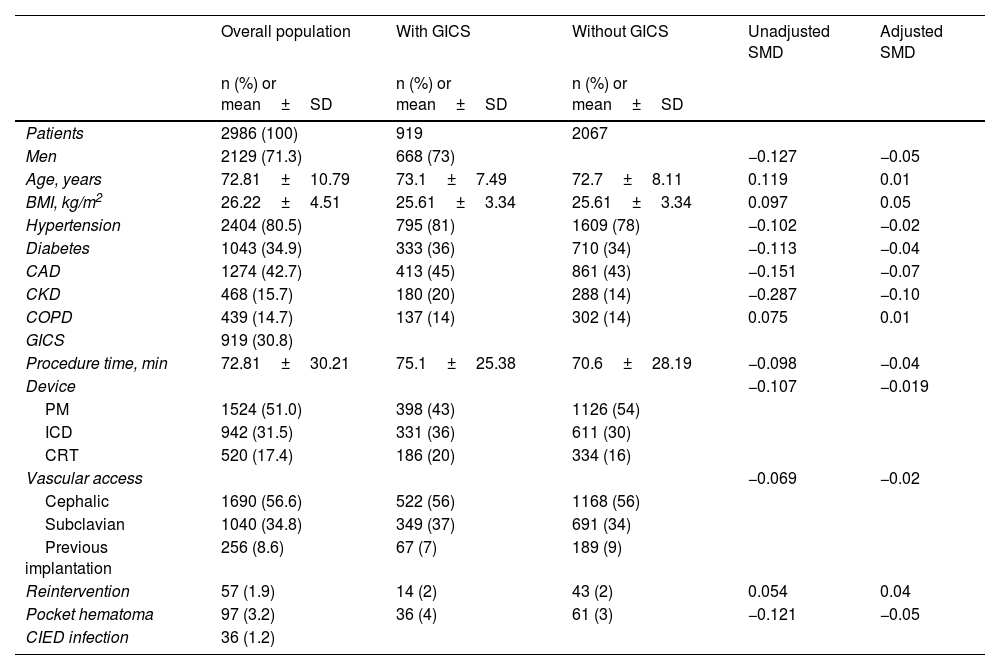

ResultsA total of 2986 patients were included in the present study. Baseline and demographic characteristics and clinical features of the overall population are summarized in Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population.

| Overall population | With GICS | Without GICS | Unadjusted SMD | Adjusted SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or mean±SD | n (%) or mean±SD | n (%) or mean±SD | |||

| Patients | 2986 (100) | 919 | 2067 | ||

| Men | 2129 (71.3) | 668 (73) | −0.127 | −0.05 | |

| Age, years | 72.81±10.79 | 73.1±7.49 | 72.7±8.11 | 0.119 | 0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.22±4.51 | 25.61±3.34 | 25.61±3.34 | 0.097 | 0.05 |

| Hypertension | 2404 (80.5) | 795 (81) | 1609 (78) | −0.102 | −0.02 |

| Diabetes | 1043 (34.9) | 333 (36) | 710 (34) | −0.113 | −0.04 |

| CAD | 1274 (42.7) | 413 (45) | 861 (43) | −0.151 | −0.07 |

| CKD | 468 (15.7) | 180 (20) | 288 (14) | −0.287 | −0.10 |

| COPD | 439 (14.7) | 137 (14) | 302 (14) | 0.075 | 0.01 |

| GICS | 919 (30.8) | ||||

| Procedure time, min | 72.81±30.21 | 75.1±25.38 | 70.6±28.19 | −0.098 | −0.04 |

| Device | −0.107 | −0.019 | |||

| PM | 1524 (51.0) | 398 (43) | 1126 (54) | ||

| ICD | 942 (31.5) | 331 (36) | 611 (30) | ||

| CRT | 520 (17.4) | 186 (20) | 334 (16) | ||

| Vascular access | −0.069 | −0.02 | |||

| Cephalic | 1690 (56.6) | 522 (56) | 1168 (56) | ||

| Subclavian | 1040 (34.8) | 349 (37) | 691 (34) | ||

| Previous implantation | 256 (8.6) | 67 (7) | 189 (9) | ||

| Reintervention | 57 (1.9) | 14 (2) | 43 (2) | 0.054 | 0.04 |

| Pocket hematoma | 97 (3.2) | 36 (4) | 61 (3) | −0.121 | −0.05 |

| CIED infection | 36 (1.2) |

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CIED: cardiac implantable electronic device; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy device; GICS: gentamicin-impregnated collagen sponges; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM: pacemaker; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardized mean difference.

The mean age of the study population was 72.81±10.79 years and patients were predominantly men (71.3%). A large proportion of patients presented major cardiovascular risk factors. Specifically, 2404 (80.5%) patients had hypertension, 1043 (34.9%) had diabetes, 1274 (42.7%) had CAD, 439 (14.7%) had COPD and 468 (15.7%) had eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The majority of patients (52.5%) were in NYHA functional class II. Among CIEDs in the study, 1524 (51%) were pacemakers (single- or dual-chamber), 942 (31.5%) were ICDs (single- or dual-chamber), and 520 (17.4%) were CRTs. Most procedures were performed via the cephalic vein (56.6%), followed by the subclavian vein (34.8%). Lastly, 8.6% of patients underwent elective generator replacement. A total of 57 patients underwent reintervention (1.9%). Pocket hematoma was found in 97 (3.2%) patients. CIED-related infections occurred in 36 patients (1.2%).

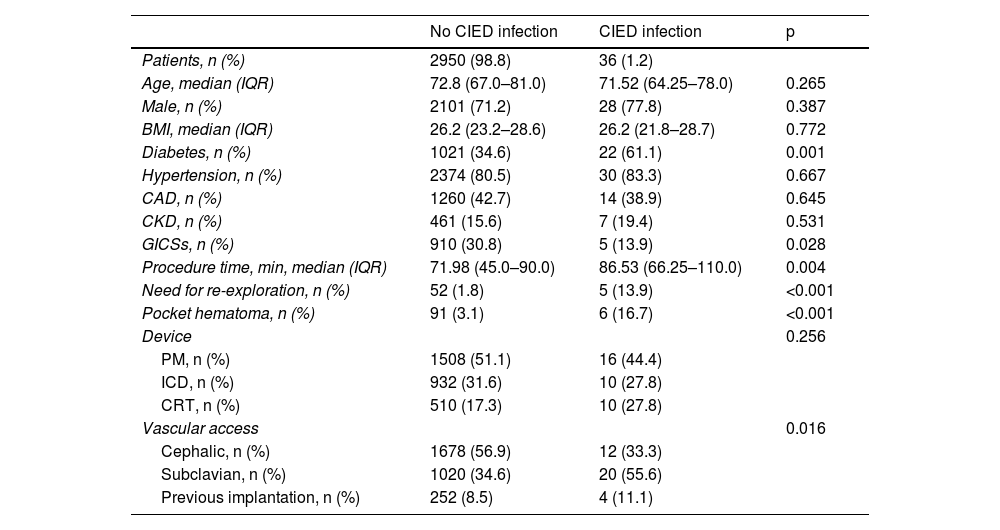

Our results showed a higher prevalence of diabetes in patients with early infection than in those without (61.1% vs. 34.6%, p 0.001) (Table 2).

Comparison between patients with and without cardiac implantable electronic device infection.

| No CIED infection | CIED infection | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 2950 (98.8) | 36 (1.2) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 72.8 (67.0–81.0) | 71.52 (64.25–78.0) | 0.265 |

| Male, n (%) | 2101 (71.2) | 28 (77.8) | 0.387 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.2 (23.2–28.6) | 26.2 (21.8–28.7) | 0.772 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1021 (34.6) | 22 (61.1) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2374 (80.5) | 30 (83.3) | 0.667 |

| CAD, n (%) | 1260 (42.7) | 14 (38.9) | 0.645 |

| CKD, n (%) | 461 (15.6) | 7 (19.4) | 0.531 |

| GICSs, n (%) | 910 (30.8) | 5 (13.9) | 0.028 |

| Procedure time, min, median (IQR) | 71.98 (45.0–90.0) | 86.53 (66.25–110.0) | 0.004 |

| Need for re-exploration, n (%) | 52 (1.8) | 5 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Pocket hematoma, n (%) | 91 (3.1) | 6 (16.7) | <0.001 |

| Device | 0.256 | ||

| PM, n (%) | 1508 (51.1) | 16 (44.4) | |

| ICD, n (%) | 932 (31.6) | 10 (27.8) | |

| CRT, n (%) | 510 (17.3) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Vascular access | 0.016 | ||

| Cephalic, n (%) | 1678 (56.9) | 12 (33.3) | |

| Subclavian, n (%) | 1020 (34.6) | 20 (55.6) | |

| Previous implantation, n (%) | 252 (8.5) | 4 (11.1) |

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CIED: cardiac implantable electronic device; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy device; GICSs: gentamicin-impregnated collagen sponges; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM: pacemaker; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardized mean difference.

In addition, we found a higher prevalence of CIED infection with subclavian than with cephalic vein access (55.6% vs. 34.6%, p=0.001). We also observed that patients with CIED infection had longer procedure time (86.5 min [66.2–110 min] vs. 71.9 min [45.0–90.0 min], p=0.004). Moreover, we noted that a second reintervention increased the risk of infection (13.9% vs. 1.8%, p<0.001).

The efficacy of treatment with GICSs was tested by propensity score matching. Treatment efficacy proved to be statistically significant in treated patients ([95% CI] 0.03–0.001, p<0.001). The results of conditional logistic regression based on propensity score are summarized in Table 3.

Conditional regression for main risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection.

| Treatment with GICSs | SE | z | p | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATE | 0.004 | −3.49 | <0.001 | −0.219 to −0.006 | |

| ATET | 0.007 | −2.20 | <0.001 | −0.031 to −0.001 | |

| Independent risk factors for CIED infection | |||||

| Diabetes | 0.35 | 1.07 | 0.002 | 2.915 | 1.465–5.799 |

| GICSs | 0.49 | −1.16 | 0.019 | 0.312 | 0.0528–0.6119 |

| Procedure time | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 1.021 | 1.008–1.034 |

| Need for re-exploration | 0.53 | 2.20 | <0.001 | 9.065 | 3.180–25.837 |

| Pocket hematoma | 0.49 | 2.40 | <0.001 | 11.023 | 4.195–28.961 |

ATE: average treatment effect; ATET: average treatment effect on the treated; CI: confidence interval; CIED: cardiac implantable electronic device; GICSs: gentamicin-impregnated collagen sponges; OR: odds ratio; SE: standard error.

The need for reintervention appeared to be one of the main predictors of CIED infection (OR 9.0 [95% CI 3.180–25.837], p<0.001), together with diabetes (OR 2.9 [95% CI 1.465–5.799], p=0.002), and procedure time (OR 2.9 [95% CI 1.008–1.034], p=0.001). Finally, pocket hematoma was the major contributor to the development of infections (OR 11.0 [95% CI 4.195–28.961], p<0.001).

DiscussionThe results of the present study show that reintervention, prolonged procedure time, pocket hematoma, and diabetes are independent risk factors for the development of CIED infection. After propensity score matching, treatment with GICSs was shown to be effective in reducing infections in our analysis. Although infection associated with CIED implantation is a serious complication with high morbidity and mortality, to date no study has tested the efficacy of GICSs in preventing CIED infection.

The main predictors of CIED infection that we found agree with several previous analyses.2,12 A large prospective study in 2007 showed that early reintervention was associated with an increased risk of developing a perioperative infection.13 A more recent review also confirmed that CIED infection was often related to the complexity of the procedure and early re-exploration of the pocket, which may confer an increased infectious risk.14 In particular, Cheng et al. observed 13%, 17%, and 37% increased risk for every 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min of surgery, respectively.15,16 According to our results, subclavian vascular access was also associated with a higher relative risk of SSI. This may be due to the routine use of cephalic venous access in our institution. Subclavian venous access is performed as a second choice or in the event of failure of cephalic insertion. Therefore, in these cases, the procedural time is generally longer. Other observational studies have shown that implantation performed via subclavian vein puncture was associated with CIED infections.17,18 However, recent meta-analyses comparing subclavian vein puncture and axillary vein puncture versus cephalic vein access showed no significant increase in the risk of infection.19 We also observed that the prevalence of diabetic patients was higher in the CIED infection group. As widely recognized, these patients are known to have a higher overall infection risk, as well as an increased risk of developing hospital-related infections.20,21

Another known risk factor for infection is pocket hematoma.19,21,22 As reported above, this represented one of the most important predictors of CIED infection in our population.

To date, evidence on prophylactic strategies to prevent device infections is limited.23–25 The WRAP-IT trial26 aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of antibiotic-eluting absorbable envelopes in reducing the incidence of CIED-associated infections. They significantly reduced the incidence of CIED infections in high-risk patients without an increased incidence of complications. However, routine use is limited by availability and high costs.3 Other preventive strategies for cardiac device infections are pocket irrigation with antibiotic agents, the benefit of which, however, is still debated.27–29 The recent PADIT score showed that the risk of infection increases with the type of procedure and subsequent reinterventions.2 However, the trial did not analyze any strategies to prevent CIED infection, nor did it consider the effectiveness of GICSs or any impact they may have on CIED infections.

GICSs have been widely used in surgical procedures and their preventive role in the development of SSI is well known.30–32 However, no evidence is available in the literature on the use of GICSs in CIED implantations. Ours is the first study to show that the addition of GICSs to routine antibiotic therapy during procedures is associated with a significant reduction in CIED infections. Moreover, the cost of GICSs is significantly lower than that of other proposed tools, potentially saving the costs of CIED infection management with minimal use of resources.3 The efficacy of GICSs is supported by propensity score matching analysis, which enabled us to overcome the limitations imposed by the observational nature of the study.

Study limitationsOur study has some limitations. The results obtained are based on the analysis of a single university hospital center population. Since CIED infections are a relatively rare event, predictors of infection risk may vary worldwide. Therefore, the efficacy of GICSs needs to be tested in randomized trials before they become routine practice.

ConclusionThis study demonstrated for the first time the effectiveness of using GICSs in reducing CIED infection. Reintervention, pocket hematoma, diabetes, and procedure time are independent risk factors for the development of CIED infection.

Ethics approvalThis is a retrospective observational study. The Tor Vergata University Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Andrea Matteucci, Michela Bonanni and Gianluca Massaro. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Andrea Matteucci and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.