A 72-year-old man with severe lactose intolerance was admitted for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The coronary angiogram revealed occlusion of the distal third of the first diagonal artery and several non-significant lesions. The pre-discharge echocardiogram revealed moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy, rosuvastatin, perindopril and carvedilol, he was repeatedly readmitted in the following days for abdominal pain/bloating, diarrhea and nausea despite avoiding food products containing lactose. To date, there has been no comprehensive study on the relationship between lactose intolerance and coronary disease, nor has its impact on therapeutics been appropriately addressed. Intolerance to lactose-containing prescription medicines is an extremely rare phenomenon and few strategies are available to overcome this condition, as it has received little attention from the scientific community. Commercial forms of the lactase enzyme and probiotics can limit symptom severity, but different routes of administration, different brands of the same medicine or completely different medicines may be necessary. Some measures were proposed to our patient and, soon afterwards, he was completely asymptomatic in both gastrointestinal and cardiovascular terms.

Um indivíduo de 72 anos, sexo masculino, com história de intolerância severa à lactose, foi admitido por enfarte agudo do miocárdio sem supradesnivelamento do segmento ST. A coronariografia revelou oclusão do terço distal da primeira artéria diagonal e múltiplas lesões não significativas, enquanto o ecocardiograma pré-alta revelou disfunção ventricular esquerda de grau moderado. O doente teve alta, medicado com dupla-antiagregação (ácido acetilsalicílico e clopidogrel), rosuvastatina, perindopril e carvedilol, porém foi repetidamente re-admitido nos dias seguintes por quadro de dor abdominal, flatulência, diarreia e náusea, apesar da evicção de produtos alimentares contendo lactose. Até este momento, a relação potencial entre a intolerância à lactose e a doença coronária não foi adequadamente avaliada, e nenhum estudo atentou no impacto daquela condição na qualidade e diversidade da terapêutica cardiovascular necessária em doentes com patologia cardíaca. A intolerância a medicamentos contendo lactose é um fenómeno extremamente raro, sendo também raras as estratégias para ultrapassar esta situação, tendo em conta a escassa atenção que este tema mereceu da comunidade internacional. Formas comerciais da enzima lactase e probióticos podem limitar a severidade dos sintomas, porém habitualmente formas diferentes de administração, diferentes formulações da mesma substância ou mesmo substâncias alternativas são necessárias. Algumas medidas foram propostas ao doente em causa e, uma semana depois, o mesmo apresentava-se completamente assintomático dos pontos de vista gastrointestinal e cardiovascular.

A 72-year-old male patient was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. He had a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking (90 pack-years) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. His daily medication included a budesonide/formoterol inhalation aerosol. He mentioned aspirin allergy and severe lactose intolerance, diagnosed during adolescence, which he had learned to control with strict diet restrictions. Irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease and Crohn's disease were excluded in adulthood.

The coronary angiogram revealed occlusion of the distal third of the first diagonal artery and diffuse coronary artery disease with multiple non-significant atherosclerotic lesions throughout the coronary tree. The pre-discharge echocardiogram was suggestive of ischemic cardiomyopathy with moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel/triflusal), rosuvastatin, perindopril and carvedilol, he was repeatedly readmitted for flatulence, abdominal pain and bloating, diarrhea and nausea, a clinical picture compatible with lactose intolerance, “exactly the same” as he had felt whenever he consumed lactose-containing food. Following each admission the patient denied chest pain and dyspnea and the physical exam was unremarkable. In each case, following exclusion of peptic ulcer and gastritis, ischemic colitis and recurrent myocardial ischemia, he was discharged from the emergency department.

After his third readmission, he suspended all medication on his own initiative. Soon afterwards, all symptoms disappeared and did not recur until the moment he restarted taking his medication. The cycle was repeated, with the same results.

At his first cardiology follow-up visit, the patient anxiously asked for advice. His blood pressure and cholesterol levels were uncontrolled and, although denying recurrent angina, he mentioned moderate effort fatigue and dyspnea compatible with NYHA class II heart failure.

DiscussionAdult-type hypolactasia, characterized by down-regulation of lactase enzyme activity in the intestine during development, is the most common human enzyme deficiency. Symptoms caused by undigested lactose are non-specific, vary greatly in severity, depend on the amount of lactose ingested, individual sensitivity and the amount and type of colonic flora, and may overlap with those of other gastrointestinal diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome or those presenting with secondary lactose malabsorption such as celiac disease. It is important to distinguish hypolactasia, a low level of lactase not necessarily associated with symptoms, from clinical lactose intolerance resulting from congenital complete loss of lactate (very rare), inherited loss after weaning (common) or secondary intestinal damage (from rotavirus or Giardia infections). Accurate diagnosis of lactose malabsorption through lactose tolerance or breath hydrogen tests is cost-effective and time-saving considering lactose intolerance is easily treatable by diet modification in most cases.

Brief mention should be made of the important difference between cow's milk allergy and cow's milk intolerance. The latter condition is an immunologically mediated reaction to cow's milk proteins that may involve the gastrointestinal tract, skin, respiratory tract, or even multiple systems (potentially causing systemic anaphylaxis). Cow's milk allergy does not interfere with lactose-containing prescription medicines.1

To our knowledge, to date no comprehensive review on the relationship between lactose intolerance and cardiovascular disease has been published, nor has its impact on therapeutics been appropriately addressed. There is surprisingly little in the literature on therapeutic considerations in these patients.

Older studies suggested that a diet relatively low in lactose, in populations with a low prevalence of lactose absorbers, consistently protects against ischemic heart disease,2 and that lactose could be the dietary factor responsible for increased risk of coronary artery disease.3 These studies had serious limitations, however, and a more recent meta-analysis of cohort studies concluded that milk consumption actually correlates with a small but significant reduced risk of coronary disease.4 Lactose intolerance usually leads to lower calcium intake from dairy foods, which increases risk of diabetes and hypertension.5 A low intake of calcium and other dairy-related nutrients (potassium and magnesium), especially in African-Americans,6 may exacerbate the risk of developing hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, colon cancer and obesity.

Some studies indicate lactose is not a major cause of symptoms for lactose maldigesters following normal intake of dairy foods. People identifying themselves as severely lactose-intolerant may mistakenly attribute a variety of abdominal symptoms to lactose intolerance, although symptoms are likely to be negligible if lactose intake is limited to the equivalent of ≤240ml of milk a day.7 However, even though persistent severe gastrointestinal symptoms may indicate another disorder, some case reports of factual severe lactose intolerance have been published, including examples of intolerance to (low) lactose-containing over-the-counter or prescription medicines and vitamin supplements.8 Understandably, patient discomfort subsequently affects compliance with medication.

Lactose is widely used in pharmaceutical formulations as a diluent or carrier. This includes prescription drugs and over-the-counter and complementary medicines. The lactose content of oral medications is generally small in comparison to the amount of lactose in many dietary substances, particularly dairy products, and the low dose of lactose in most conventional oral solid-dosage form pharmaceuticals (usually <2g per day) is unlikely to cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms unless the patient has severe lactose intolerance (even considering cumulative exposure to more than one lactose-containing drug). A randomized double-blind crossover controlled trial that included 77 patients with lactose malabsorption and symptoms of intolerance showed no statistically significant difference in breath hydrogen excretion or severity of gastrointestinal symptoms following ingestion of lactose compared to placebo. The authors suggested lactase deficiency should not be considered a contraindication to the use of medicines containing ≤400mg lactose.9

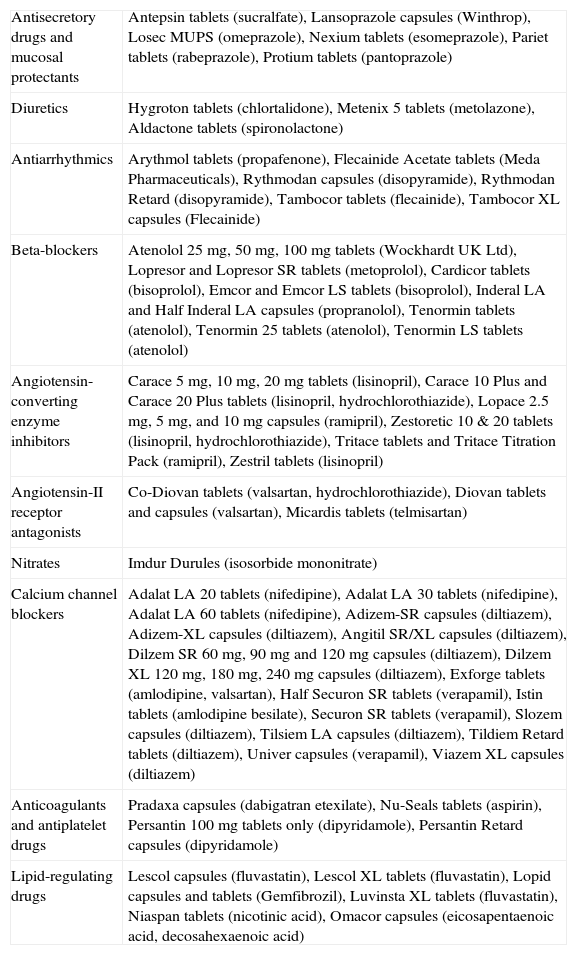

According to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain's Information Centre,10 all drugs initially prescribed to our patient contain lactose. The patient asked for advice and, according to the literature, several options may be considered:

- •

Commercial forms of the lactase enzyme, in liquid or tablet form, could limit the severity of our patient's symptoms when taken concomitantly with his medication. However, no studies have evaluated whether supplementation with lactase could have any pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interactions with cardiovascular drugs. Nitroglycerine formulations require lactose for stability purposes.

- •

Supplementation with probiotics (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp.) may modulate gut microbial composition, leading to improvement in gut health and lactose intolerance symptoms.11

- •

Although information regarding the quantity of lactose in each drug is not easily available, the amount differs in different drugs or even different formulations of the same drug. Replacement of all drugs is not usually advocated, but must be considered in patients who are particularly lactose-sensitive. Different routes of administration, different brands of the same medicine or completely different medicines may be necessary. Liquid preparations of most medicines are lactose-free. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society's Information Pharmacists10 have developed a list of lactose-free medicines, some of which are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.Some lactose-free medicines potentially useful for treating cardiovascular conditions, according to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain's Information Centre.10

Antisecretory drugs and mucosal protectants Antepsin tablets (sucralfate), Lansoprazole capsules (Winthrop), Losec MUPS (omeprazole), Nexium tablets (esomeprazole), Pariet tablets (rabeprazole), Protium tablets (pantoprazole) Diuretics Hygroton tablets (chlortalidone), Metenix 5 tablets (metolazone), Aldactone tablets (spironolactone) Antiarrhythmics Arythmol tablets (propafenone), Flecainide Acetate tablets (Meda Pharmaceuticals), Rythmodan capsules (disopyramide), Rythmodan Retard (disopyramide), Tambocor tablets (flecainide), Tambocor XL capsules (Flecainide) Beta-blockers Atenolol 25 mg, 50mg, 100mg tablets (Wockhardt UK Ltd), Lopresor and Lopresor SR tablets (metoprolol), Cardicor tablets (bisoprolol), Emcor and Emcor LS tablets (bisoprolol), Inderal LA and Half Inderal LA capsules (propranolol), Tenormin tablets (atenolol), Tenormin 25 tablets (atenolol), Tenormin LS tablets (atenolol) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors Carace 5mg, 10mg, 20mg tablets (lisinopril), Carace 10 Plus and Carace 20 Plus tablets (lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide), Lopace 2.5mg, 5mg, and 10mg capsules (ramipril), Zestoretic 10 & 20 tablets (lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide), Tritace tablets and Tritace Titration Pack (ramipril), Zestril tablets (lisinopril) Angiotensin-II receptor antagonists Co-Diovan tablets (valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide), Diovan tablets and capsules (valsartan), Micardis tablets (telmisartan) Nitrates Imdur Durules (isosorbide mononitrate) Calcium channel blockers Adalat LA 20 tablets (nifedipine), Adalat LA 30 tablets (nifedipine), Adalat LA 60 tablets (nifedipine), Adizem-SR capsules (diltiazem), Adizem-XL capsules (diltiazem), Angitil SR/XL capsules (diltiazem), Dilzem SR 60mg, 90mg and 120mg capsules (diltiazem), Dilzem XL 120mg, 180mg, 240mg capsules (diltiazem), Exforge tablets (amlodipine, valsartan), Half Securon SR tablets (verapamil), Istin tablets (amlodipine besilate), Securon SR tablets (verapamil), Slozem capsules (diltiazem), Tilsiem LA capsules (diltiazem), Tildiem Retard tablets (diltiazem), Univer capsules (verapamil), Viazem XL capsules (diltiazem) Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs Pradaxa capsules (dabigatran etexilate), Nu-Seals tablets (aspirin), Persantin 100mg tablets only (dipyridamole), Persantin Retard capsules (dipyridamole) Lipid-regulating drugs Lescol capsules (fluvastatin), Lescol XL tablets (fluvastatin), Lopid capsules and tablets (Gemfibrozil), Luvinsta XL tablets (fluvastatin), Niaspan tablets (nicotinic acid), Omacor capsules (eicosapentaenoic acid, decosahexaenoic acid)

A new prescription was accordingly prepared, consisting of lactose-free formulations of fluvastatin, metoprolol, lisinopril and isosorbide mononitrate. The patient also started taking clopidogrel concomitantly with probiotics and lactase supplementation (he is allergic to aspirin and all formulations of clopidogrel and triflusal contain lactose). Soon afterwards, he was completely asymptomatic in both gastrointestinal and cardiovascular terms.

ConclusionStudies suggest a potential correlation between lactose intolerance and hypertension or coronary artery disease. The fact that most lactose-intolerance cases are mild has erroneously devalued the need for a more comprehensive review of the implications of this condition for the treatment of patients with cardiovascular disease. The lactose content of any medications should be determined prior to prescribing by consulting the manufacturer. Our report and review should motivate more thorough research on this subject.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.