We present a case of an accidentally crushed stent due to an unnoticed passage of a guidewire through a lateral stent strut with subsequent stent compression after balloon dilatation, during a planned percutaneous coronary intervention on the left main. The crushed stent segment was reconstructed with step-by-step balloon dilation, guided by intravascular ultrasound.

Apresenta-se um caso em que durante uma angioplastia eletiva do tronco comum, devido à passagem inadvertida do fio-guia através da malha do stent, ocorreu um esmagamento do stent após a dilatação com balão. O segmento de stent danificado foi reparado através de sucessivas dilatações com balão, tendo o procedimento sido guiado por ecografia intravascular (IVUS).

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the left main (LM) is considered a valid alternative to surgical coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), with no significant difference in overall rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (death, myocardial infarction, stroke and repeat revascularization) in patients with lower (0-22) and intermediate (23-32) SYNTAX scores.1 Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is an invasive adjunctive diagnostic tool which provides accurate measurement of plaque burden and lesion severity. Additionally, IVUS helps to optimize PCI results, as target vessel revascularization is reduced in patients with IVUS-guided stenting compared to those with angiographically guided stenting.2

IVUS is strongly recommended for precise vessel measurement and correct stent apposition and expansion during LM-PCI, especially in the drug-eluting stent (DES) era.3

The case we present here is an accidentally crushed stent in the proximal LM, which would have gone unnoticed without IVUS examination. The use of IVUS enabled the identification of the crushed stent segment and the introduction of a new guidewire in this segment in order to repair the stent deformation by balloon dilatation.

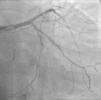

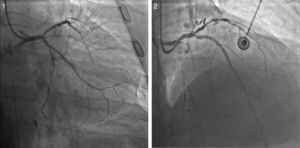

Case reportA 60-year-old-man with hypertension and type 2 diabetes as coronary risk factors was admitted to our hospital due to unstable angina. He had suffered a non-Q-wave myocardial infarction in 2006, when percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was successfully performed on the mid segment of the left anterior descending (LAD) and second obtuse marginal arteries. A coronary angiogram after the recent event showed a significant calcified lesion in the LM and ostial LAD without evidence of restenosis in the previous stents (Figures 1 and 2). The patient had severe left ventricular dysfunction, with 30% of ejection fraction. We planned PCI on the LM and LAD with intra-aortic balloon pump support.

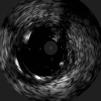

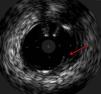

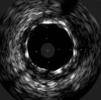

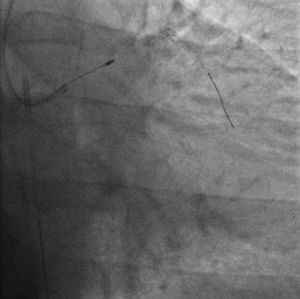

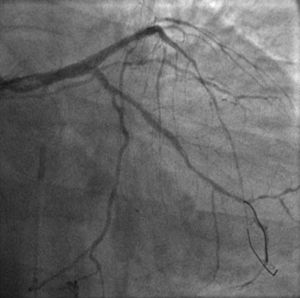

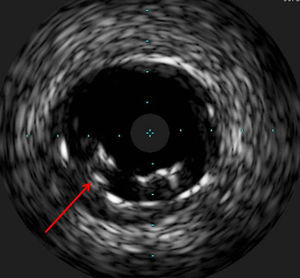

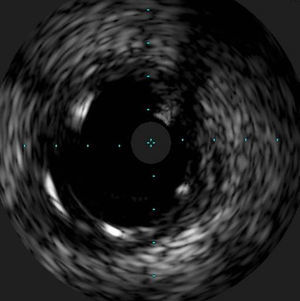

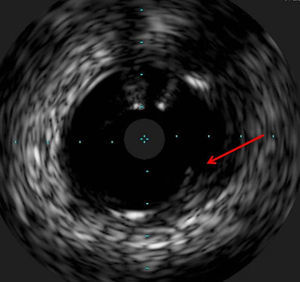

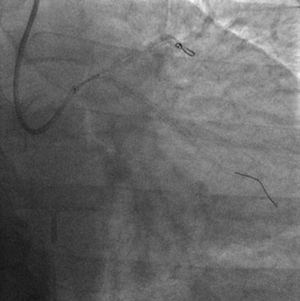

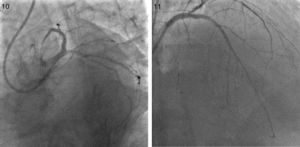

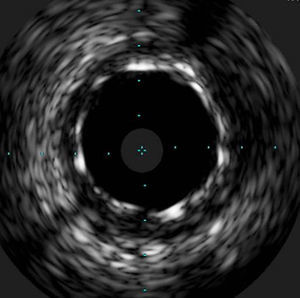

The procedure was performed by radial approach using a 7F guiding catheter. Plaque preparation was performed with rotational atherectomy using a 1.5 mm burr (Figure 3) and further predilation with a cutting balloon (3-3.5 mm). After balloon dilatation, rupture of severely calcified plaque was detected by IVUS (Eagle Eye; Volcano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA, USA), so we proceeded to implant a 3.5 mm×20 mm CRE 8 DES in the LM and LAD (Figures 4 and 5). At this point the wire was accidentally pulled back and was reintroduced into the LM and LAD. Post-dilatation was performed with a 4 mm non-compliant balloon. IVUS examination with manual pull-back at this stage revealed that the proximal part of the stent in the LM had been crushed as a result of lateral reintroduction of the wire through a proximal stent strut. The patient remained stable with normal flow in the LM and LAD. Guided by IVUS, a second wire (Sion, Asahi Intecc, Japan), with a 30° bend in its 1 mm distal tip, was introduced within the crushed stent segment (Figure 6). Once the guidewire was positioned inside the stent, progressive dilations with small (1.5 mm) to large (4 mm) balloons were performed until the stent regained its cylindrical shape (Figure 7). IVUS exploration detected an image suggesting dissection in the proximal end of the stent (Figure 8), and so a second DES (4 mm×8 mm Onyx) was implanted in the ostial-proximal segment of the LM, overlapping the previous stent (Figure 9), with an adequate angiographic final result (Figures 10 and 11). IVUS revealed correct stent expansion and apposition in the LM (Figure 12).

The case presented here is a rare complication produced by accidental wire withdrawal during a LM-PCI. The wire was reintroduced proximally and laterally through a proximal stent strut and subsequent dilatation with a 4 mm non-compliant balloon caused stent crushing in its proximal segment. This event was partly due to an underexpanded stent segment in the LM related to the size of the stent (3.5 mm). IVUS was crucial in this case to identify the problem despite an almost normal angiographic image, and it enabled the introduction of a wire into the correct lumen and the reconstruction of the crushed segment after multiple balloon dilatations. Another useful technique to detect lateral stent compression would have been stent boost imaging, but this was not available in our catheterization laboratory at the time the procedure was performed.

It is well known that mechanical problems related to stent deployment can contribute to stent restenosis and IVUS can play a key role in identifying this kind of problem during PCI.4

This case highlights the importance of appropriate stent size and correct stent apposition to the vessel wall, especially in the context of LM-PCI. The easy reintroduction of the wire laterally through a stent strut was probably due to stent underexpansion in the LM. We had chosen a 3.5 mm stent in this case because of a mismatch between the LM and the proximal segment of the LAD but with the intention of performing proximal stent post-dilation with a 4 mm balloon. The operator did not in fact feel any unusual resistance in advancing the wire and the 4 mm non-compliant balloon through the stent strut. Therefore, balloon dilatation at this point caused the stent crush, without specific warning signs from either an angiographic or a clinical point of view.

As the patient was stable, and taking advantage of the size of the 7F guiding catheter, we introduced a new guidewire under IVUS guidance within the lumen of the crushed stent segment. After step-by-step dilatation with smaller to larger balloons, the crushed stent segment regained its cylindrical shape. Although another practical solution would have been to implant a new stent (stent-in-stent), we chose the former strategy and consequently avoided the placement of multiple layers in the proximal segment of the LM. Finally, the implantation of a second stent, overlapping with the proximal end of the previous stent in the LM, enabled the coverage of both the proximal end dissection and the proximal part of the reconstructed stent segment. Considering that in the latter part the struts appeared to be incomplete in some circumferential points (Figure 7), the implantation of a new stent could remedy this defect.

ConclusionThe case presented here demonstrates that keeping the wire in the distal part of the vessel during LM-PCI is crucial. If a wire is accidentally withdrawn, especially when the stent is not correctly appositioned, it is strongly recommended to check the wire position with IVUS once it is reintroduced into the vessel, in order to avoid potential complications such as we experienced. This unexpected problem can be resolved by introducing the wire within the crushed stent segment under IVUS guidance and by further balloon dilatation.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.