The study presented by Silva1 et al., in the current issue of the Portuguese Journal of Cardiology, is, in my view, very important. There are several reasons to acknowledge its value. Firstly, it was designed by family doctors – a wide-ranging designation for what are widely known as primary care physicians. Arguably, these doctors are often misunderstood, buried in a multitude of patients, with a wide variety of diagnoses to be managed and ever-increasing bureaucracy. The present study, in this context, is a victory. Secondly, this study tries to bridge the gap between doctors who usually treat diabetes and the vascular procedure “hospital folk” – cardiologists, vascular and heart surgeons among others.

Type 2 diabetes (DM) is an important piece of the vascular risk puzzle and, yes, it is on the rise, with an estimated prevalence in Portugal of 14.1% (1.1 million people, between 20 and 79 years old).2 It is usually wrapped in a bundle with other very common risk increasing comorbidities, such as hypertension3 and, often, as this work clearly shows, is the harbinger of vascular complications. Therefore, in a broad interpretation, diabetes can be viewed as a vascular disease.

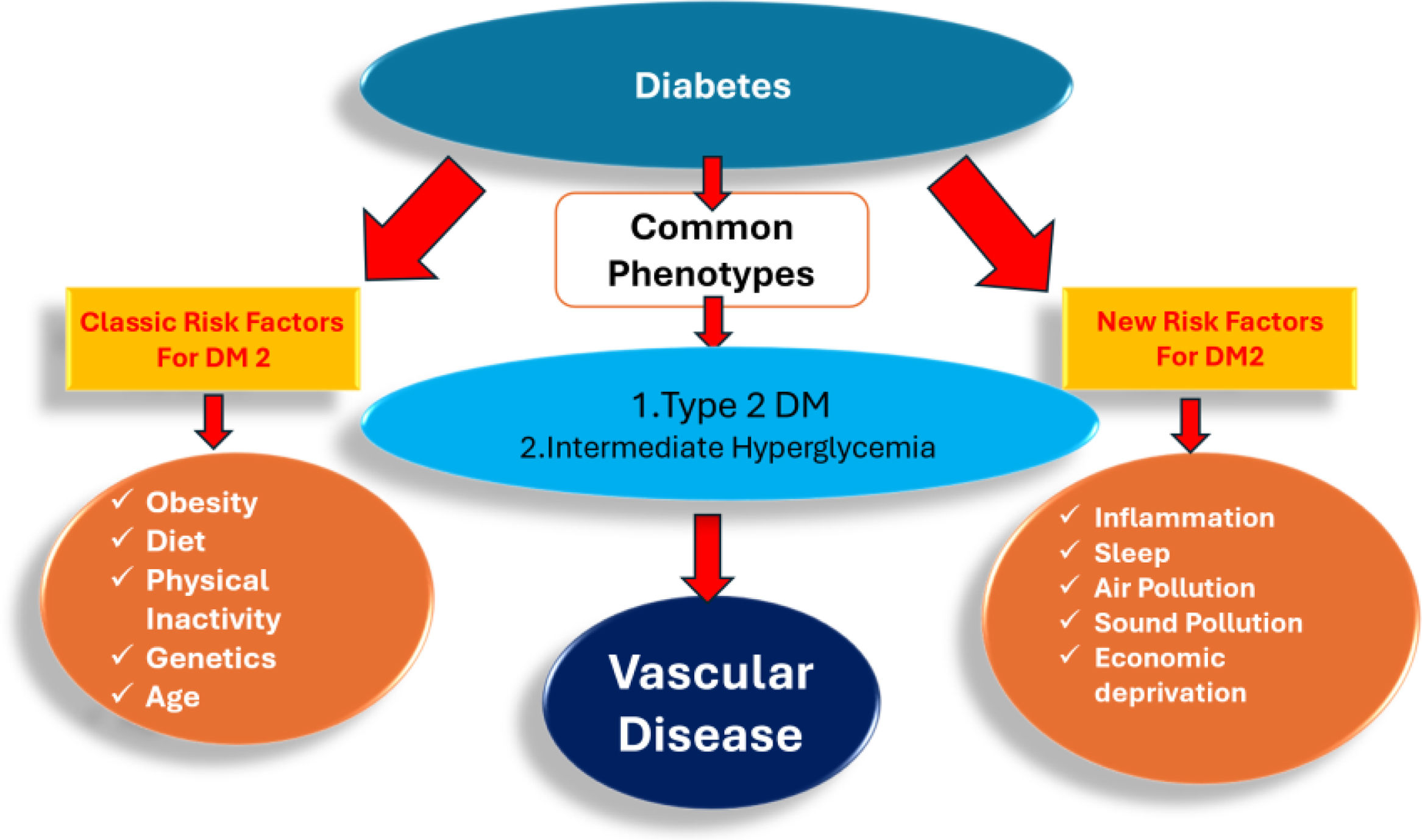

However, for the community interested in reducing global cardiovascular risk, two phenotypes for hyperglycemia are relevant in the general population: type 2 DM and what is known as intermediate hyperglycemia (IH), which is very common and also associated with high cardiovascular risk.4 IH refers to fasting hyperglycemia or glycemic intolerance (some patients have one of these traits or both, without meeting the criteria for a diabetes diagnosis) – see Figure 1.

Diabetes presentation from an epidemiological cardiovascular risk point-of-view. Intermediate hyperglycemia refers to fasting hyperglycemia and/or glucose intolerance, not meeting the accepted criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes. Intermediate hyperglycemia is estimated in Portugal, between ages 20 and 79 years old, is as follows: fasting hyperglycemia 10.8%; decreased glucose tolerance 14.9%; both traits 2.9% of the population. Total prevalence for clinical relevant hyperglycemia is 42.7%.2

Intermediate hyperglycemia is not addressed in this study (probably because its existence is less valued), however, one could even speculate that it is the commonest of “civilizational” hyperglycemia. There are several reasons for the increase in “civilizational” hyperglycemia in our midst. The most important factors are related to changes in lifestyle, including lack of physical activity and diet, as societies have changed from agricultural production or physical demanding industries to services in an ever growing digital environment, topped by major urbanization. This trend is now also present in less developed countries.5 Other risk factors, which are gaining increasing importance in the cardiovascular realm are environmental factors, mainly related to increasing oxidative stress and social anxiety, both connected to vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction – the cornerstone for the development of atherosclerosis.6,7

cMORE was a non-interventional, cross-sectional, multicenter study conducted in 32 Portuguese primary healthcare units between October 2020 and 2022, which is truthfully the basis for solid real-world work. The data collected, including sociodemographic, anthropometric and clinical information, cardiometabolic comorbidities, HbA1c levels, lipid parameters and medication, stem from electronic medical records. Portugal has in place a set of indicators for public primary practice, known as “BI-CSP”. These data have also been used successfully in an ongoing country wide hypertension intervention.8

In the 780 patients selected, the long duration of disease (10.5 years average), the heavy multimorbidity burden, including obesity, dyslipidemia and, as expected, hypertension are noteworthy, yet no surprise. Age is, of course, an important factor in diabetes, increasing the risk for retinopathy and CV disease procedures. In contrast, the findings of such a good HgA1c average level (7%) are worthy of comment: (1) hospital experience, with cardiovascular diabetes patients is not so good, and clearly present much higher HgbA1c values; (2) this might be due to the added severity of hospital diabetic patients, or to the data collecting, since there are critics of the “BI-CSP” data collection pitfalls, as the authors duly mention. Importantly, this work reports what most doctors have witnessed: longer duration of disease and higher HgbA1c are related to an increase in vascular disease. Finally, this study also points to the therapeutic trends, addressing the need to move from classic antidiabetic medications, to the newer SGLT2 inhibitors: 34.2% usage in the population studied. Insulin therapy was associated with an increase in vascular interventions, most likely due to the late introduction of insulin in tipe 2 DM. In truth, reducing therapeutic inertia and easy hospital referral may also be the key to future improvements in the management of these patients.9

This study demonstrates the substantial burden of vascular complications/comorbidities among Portuguese diabetes patients. Microvascular complications, including chronic kidney disease, micro and macroalbuminuria, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic retinopathy, and diabetic foot infections, were observed in 38.1% of patients, while macrovascular complications, such as CV diseases and procedures, were present in 19.6% of the included patients. Nevertheless, we do believe that larger scale studies with extended follow-up periods could provide further understanding of the long-term outcomes of these management strategies and their impact on patient health – as the authors stressed. A future study should address IH, the diagnosis of which is easily overlooked, and adds to the burden of hyperglycemic-related vascular events.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.