Potassium (K+) plays a key role in maintaining normal cell function. Moreover, it is the most abundant cation in humans and mostly found in intracellular compartments (98%).1 Several established homeostatic mechanisms act in a complementary fashion to maintain plasma K+ levels between 3.5–5.0 mmol/L despite marked variation in dietary K+ intake.1 However, dyskalemia can occur and adversely affect cellular transmembrane resting potential, leading to increased cell automaticity, excitability and QT prolongation or shortening in hypo- or hyperkalemia, respectively.2

Dyskalemia is common in heart failure (HF), mostly due to several co-existing HF comorbidities affecting K+ levels (e.g., chronic kidney disease, diabetes and advanced age), as well as the effects of commonly used HF drugs (e.g. diuretics, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor or beta-blockers).3 K+ derangement can limit guideline-directed medical therapy as well as lead to serious life-threatening conditions such as ventricular arrythmias or sudden cardiac death.3,4 Accordingly, previous studies show that both hypo- and hyperkalemia are associated with adverse events in chronic HF patients.5,6

However, data on the importance of dyskalemia in acute HF patients remain scarce. To assess the correlation between K+ levels and clinical outcomes in acute HF patients, we performed a single center retrospective observational cohort study enrolling consecutive patients admitted for acute HF at a HF unit from 2017 to 2018 (in those with multiple readmissions, only the first hospitalization was considered). HF and acute HF were defined according to current HF guidelines. Our goal was to assess which K+ levels (at admission or discharge) were predictors of HF readmission or all-cause mortality at 90 days post-discharge.

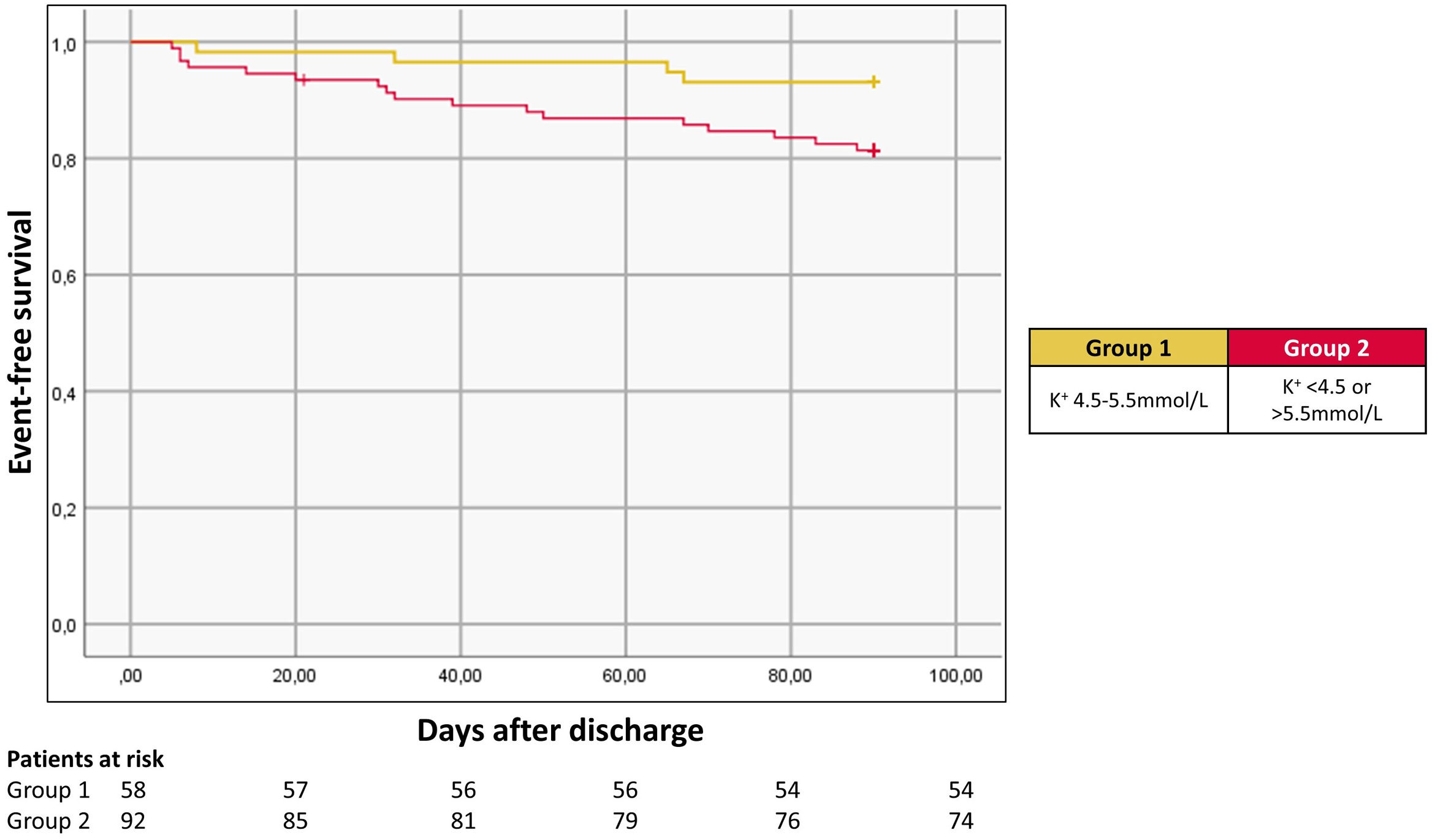

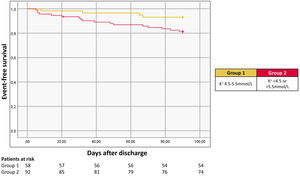

Overall, 150 patients were included (54% male; mean age 77±11 years; 46% with preserved ejection fraction; 59% with chronic kidney disease defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate assessed by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula <60 mL/min/1.73 m2); 42% with diabetes. Approximately 72% of patients were treated with a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor and 79% were on beta-blockers. Mean K+ levels at admission and discharge were 4.6±0.7 mmol/L and 4.3±0.5 mmol/L, respectively. Overall, 49%, 41% and 10% had K+ levels <4.5 mmol/L, 4.5–5.5 mmol/L and >5.5 mmol/L at admission, respectively; 64%, 33% and 3% had K+ levels <4.5 mmol/L, 4.5–5.5 mmol/L and >5.5 mmol/L at discharge, respectively. When assessing HF rehospitalization at 90 days post-discharge according to admission K+ levels, a “U” curve phenomenon was observed, with K+ levels outside of a 4.5–5.5 mmol/L range being associated with a higher risk at multivariate analysis (adjusted odds ratio: 2.5, 95% confidence interval (1.1; 5.6), p=0.021 (Figure 1). Admission K+ levels did not predict all-cause mortality at 90 days. Similarly, discharge K+ levels were not associated with either HF readmission or all-cause mortality at 90 days. Our main study findings were as follows: (1) K+ levels at admission (but not at discharge) are strongly correlated with HF readmissions at 90 days; (2) K+ levels between 4.5–5.5 mmol/L seem to portray a lower risk of HF readmission at 90 days post-discharge.

Recognizing the importance of dyskalemia in acute and chronic HF patients is critical given its prognosis implications if it remains untreated. Based on our data, K+ levels outside of a 4.5–5.5 mmol/L at admission predicts a higher risk for adverse events in acute HF patients – as such, K+ levels at admission may serve as a useful risk stratification tool in these patients. Whether dyskalemia is a risk factor or a risk marker representing the patient's overall clinical severity (which would explain its association with a higher risk for HF rehospitalization) remains to be determined.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.