In Portugal, up to 38% of the population has cardiovascular disease, which highlights the importance of primary health care (PHC) in its management.

Adequate management of people with cardiovascular disease often requires hospital referral for a cardiology consultation. However, it is not always easy to ascertain which situations should be referred, especially given that PHC does not have access to all diagnostic exams recommended by international guidelines, such as natriuretic peptides in heart failure or computed tomography coronary angiogram in chronic coronary syndromes, among others.

The aim of this document is to describe a practical approach to the most frequent heart diseases that may require a referral for a hospital cardiology consultation. Thus, in the different chapters, the recommendations for referral are highlighted generically according to group of disease, as well as, albeit briefly, the initial clinical approach within the scope of PHC for a differential diagnosis and more efficient follow-up.

A modified Metaplan methodology was used. A panel of 4 cardiology specialists and 3 specialists in General and Family Medicine developed this document, which should not be taken as an official guideline, but as additional guidance for the correct referral of patients. It is therefore advisable to validate these recommendations locally with the referral hospital, as well as to be aware of the respective international and national guidelines.

Em Portugal, até 38% da população sofre de doença cardiovascular, o que salienta a importância dos cuidados de saúde primários (CSP) na sua gestão.

A gestão adequada da pessoa com doença cardiovascular obriga frequentemente à referenciação hospitalar para consulta de cardiologia. Contudo, nem sempre é fácil distinguir quais as situações mais prementes, principalmente tendo em conta que os CSP não têm acesso a todos os exames complementares de diagnóstico recomendados pelas guidelines internacionais, como por exemplo péptidos natriuréticos na insuficiência cardíaca ou angiografia por tomografia computorizada cardíaca nas síndromes coronárias crónicas, entre outros.

O objetivo deste documento é descrever uma abordagem prática às patologias do foro cardiológico mais frequentes que podem requerer uma referenciação para consulta hospitalar de cardiologia. Assim, nos diferentes capítulos são destacadas as recomendações de referenciação de forma genérica, por grupo de patologias, bem como, ainda que de forma sucinta, a abordagem clínica inicial no âmbito dos CSP para um diagnóstico diferencial e acompanhamento crónico mais eficiente.

Foi utilizada uma metodologia Metaplan modificada reunindo um painel de quatro especialistas em cardiologia e três especialistas em medicina geral e familiar que desenvolveram este documento, o qual deve ser entendido não como uma norma oficial, mas sim como um instrumento de orientação adicional para o correto encaminhamento dos doentes. É por isso aconselhada a validação local destas recomendações com o hospital de referência, bem como a leitura das respetivas guidelines internacionais e nacionais.

In Portugal, up to 38% of the population suffers from cardiovascular disease (CVD), which highlights the importance of primary health care (PHC) in its management. Among the most common diseases in the context of PHC are hypertension (27%), arrhythmias (3%), valvular diseases (2%), heart failure (HF) (2%) and chronic coronary syndromes (2%), although their prevalence may be underestimated.1,2 Given its complexity in terms of diagnosis and clinical approach, adequate management of people with CVD implies a close, effective and bidirectional communication between PHC and hospitals.3,4 In fact, a well-defined functional network with the different levels of care is of the utmost importance, which is only possible with the intervention and cooperation of all institutional and political structures.

Hospital referral, when judicious, facilitates the timely diagnosis and treatment of potentially serious situations, and if appropriate to local access limitations, contributes to the correct clinical prioritization, being also a tool for updating all the professionals involved.5

In this document, we present general guidelines for the referral of patients with cardiovascular pathologies to a cardiology hospital consultation. Additionally, suggestions are made for the initial clinical approach within PHC, with the objective of promoting a more efficient differential diagnosis and follow-up, taking into account the limitations of access of PHC to some diagnostic exams and the context of the Portuguese national referral network.

MethodsA modified Metaplan6,7 methodology was used and divided into two phases: 1) in the first phase a panel of four specialists in Cardiology and 3 specialists in General and Family Medicine convened. After a presentation by the moderator, the panel discussed and defined which cardiovascular diseases were to be addressed in this document; 2) in the second phase, and based on the previous discussion, on current clinical guidelines, and on relevant scientific papers in the field, each chapter was developed by a Cardiologist and a General Practitioner (GP). Finally, the panel convened again to discuss the referral proposals, clinical approach and follow-up of these patients in the context of PHC.

Heart failureDefinition of heart failureHF is defined as a syndrome caused by an anomalous cardiac structure and/or function, leading to a blood output that is inadequate to the metabolic requirements of the heart.8 HF may be asymptomatic at an early stage, with subsequent symptoms onset.9

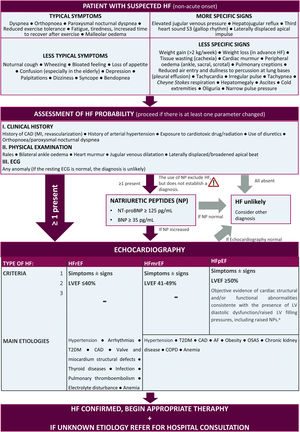

DiagnosisHeart failure diagnosis and classification algorithmFigure 1 describes the diagnosis algorithm, including typical signs and symptoms of HF, as well as the classification of HF according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).10

Diagnostic algorithm and classification of the type of heart failure.10aThe key structural changes (left atrium dilation and/or left ventricular hypertrophy) are characterized by LAVI>34 mL/m2 or an LVMI≥115 g/m2 in men and ≥95 g/m2 in women or relative wall thickness >0.42. The key functional changes are an E/e’ at rest ≥9, PA systolic pressure >35 mmHg and a TR velocity at rest >2.8 m/s. AF: atrial fibrillation; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; CAD: coronary artery disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECG: electrocardiogram; HF: heart failure; LAVI: left atrial volume index; LVMI: left ventricular mass index; MI: myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal fragment of type B natriuretic peptide; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; PA: pulmonary arterial; T2DM: type 2 diabetes; TR: tricuspid regurgitation.

In case of suspected HF, the diagnosis should be performed as soon as possible, ideally with evaluation of the results within a timeframe not exceeding two weeks to one month.11

Classification of HF based on function and cardiac structural changes is shown in Table 1.

Classification of Heart Failure regarding cardiac structural changes (ACC/AHA) and function (NYHA).28

| ACC/AHA stages | NYHA functional classification | ||

| Stage A | Risk of developing HF, with no structural cardiac changes or symptoms | Not applicable | |

| Stage B | Structural heart disease with no signs or symptoms | Class I | Asymptomatic |

| Stage C | Structural heart disease with current or previous HF symptoms | Class I | Asymptomatic |

| Class II | Symptomatic with moderate physical activity | ||

| Class III | Symptomatic with minimal physical activity | ||

| Class IV | Symptomatic at rest | ||

| Stage D | Refractory heart failure requiring specialized intervention | Class IV | Symptomatic at rest |

ACC/AHA: American Colleage of Cardiology/American Heart Association; HF: Heart Failure; NYHA: New York Heart Association

- •

Complete blood count, renal, hepatic and thyroid function, lipid profile, creatine kinase, HbA1c and glycemia (described in this document as baseline laboratory evaluation);

- •

Ferritin, % transferrin saturation ((iron/total iron-binding capacity)x100);

- •

Natriuretic peptides, according to Figure 1, if available;

- •

Urine sediment.

- •

Control of risk factors and lifestyle modification;

- •

Influenza and anti-pneumococcal vaccination;

- •

Daily weight monitoring and self-monitoring of symptoms;

- •

Avoid the use of potential harmful medication (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), COX-2 inhibitors).

The prognostic-modifying therapy of the patient with HF should include angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI)/angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), beta blockers (BB), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists – spironolactone or eplerenone (MRA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors – dapagliflozin or empagliflozin (SGLT2i), as soon as possible, in order to reduce mortality, hospitalizations for HF, and symptoms.8,10

- ∘

ACEi or ARBs should be replaced by an ARNI in suitable patients (i.e., patients that remain symptomatic).

- ∘

If an ACEi is to be substituted by an ARNI, the ARNI should only be initiated 36 hours after ACEi discontinuation.10

- ∘

Initiation of dapagliflozin and empagliflozin is not recommended in patients with an eGFR <25 and <20 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. In the case of dapagliflozin if the level of eGFR falls below 25 mL/min/1.73 m2 after initiation, there is no need for treatment discontinuation.13–15

- ∘

ARNI/ACEi/ARBs or MRAs should be prescribed with caution for patients with an eGFR<30 ml/min.

In patients with signs and/or symptoms of congestion, loop diuretics, such as furosemide, are recommended to improve and reduce symptoms and enhance exercise ability.10

Ivabradine should be considered in symptomatic patients with LVEF≤35% at sinus rhythm, and with a heart rate (HR) at rest of ≥70 beats per minute (bpm), despite treatment with BB or ACEi/ARB/MRA, or until evaluation by the cardiologist in case of contraindication for the use of BB.10

Vericiguat and digoxin may be considered in patients with worsening HF or who remain symptomatic, respectively, after cardiological evaluation.10

Devices in HFIn certain patients, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is recommended to reduce the risk of sudden death and all-cause mortality.16

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) improves cardiac performance in selected patients, improves symptoms and well-being, and reduces morbidity and mortality.17

Comorbidities- •

Anemia and/or iron deficiency

- •

Atrial fibrillation

- ∘

See chapter dedicated to AF;

- ∘

Diltiazem or verapamil should not be used.10

- •

Type 2 diabetes

- ∘

1st line: SGLT2i (reduction in risk of hospitalization for HF)19;

- ∘

Metformin can be considered if the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) >30 ml/min/1.73 m2,20;

- ∘

The use of glitazone is not recommended.21

- •

Lung diseases

- ∘

Beta blockers are only relatively contraindicated in asthma, but not in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)22;

- -

Preferable: bisoprolol or nebivolol; carvedilol can also be used9,22

- ∘

Inhaled corticosteroids are preferable to oral corticosteroids9,23;

- ∘

Noninvasive ventilation can be added to conventional therapy.9

- •

Depression

- •

Pharmacological therapy

- ∘

Loop diuretics should be used to relieve congestion27;

- ∘

The use of ARNI, ACEi/ARB, BB and MRA can be considered to reduce the risk of hospitalization due to HF or death.10

- •

Identify and treat comorbidities.

- •

Pharmacological therapy

- ∘

Loop diuretics should be used to relieve congestion.27

- •

Identify and treat comorbidities (e.g.: obesity, hypertension (HT), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), coronary artery disease (CAD), type 2 diabetes).10

- ∘

Patients with de novo HF;

- ∘

Patients with LVEF<50%.

The decision of referral to a hospital consultation should not result in a delay in the initiation/optimization of prognostic-modifying therapy (see recommended therapies mentioned), which is useful for the cardiovascular protection of the patient while waiting for a hospital consultation.

Heart failure with preserved LVEF (≥50%)28- ∘

Patients with preserved LVEF, who have had >2 hospitalizations/visits to the emergency department (ER) in one year, after excluding non-compliance with medication and lifestyle measures;

- ∘

Patients with suspected restrictive/infiltrative disease (e.g., cardiac amyloidosis);

- ∘

Patients with suspected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy;

- ∘

Patients with moderate/severe pulmonary HT.

- •

Patients with LVEF>35%, without devices, under maximum optimized therapy, without hospitalizations/decompensation episodes >1 year, with a concluded etiological evaluation.

- •

Patients without indication for further investigation and without indication for specific intervention.

- •

Before the hospital consultation:

- ∘

Clinical, analytical and electrocardiogram (ECG) reassessment when titrating disease modifying drugs;

- ∘

Repeat transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) after three to six months of maximum optimized therapy.

- •

After discharge from hospital consultation:

- ∘

Medical consultation and laboratory reassessment every six months;

- ∘

Annual ECG reassessment;

- ∘

In case the patient's clinical condition worsens, reassess ECG and TTE.

- •

In case of complications or worsening of the clinical condition, consider the possibility of contacting the referral center.

Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP)≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP)≥90 mmHg, at the doctor's office.29,30

Evaluation and risk stratification of hypertensive patients in primary healthcareOnce the diagnosis of HT has been confirmed, the patients’ assessment should meet the following objectives30:

- •

Identify signs of secondary HT;

- •

Detect target organ damage;

- •

Assist in cardiovascular risk stratification;

- •

Assess the existence of other associated pathologies that may influence the prognosis and treatment of HT.

In PHC, the GP should perform a clinical history and complete objective examination, as well as request relevant tests.29

Cardiovascular risk assessmentThe cardiovascular (CV) risk associated with the different HT stages is described in Table 2.

Stratification of total CV risk in low (yellow), moderate (orange), high (red) and very high (dark red) risk categories according to SBP and DBP.31

CV: cardiovascular; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HT: hypertension; RF: risk factors; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TOD: target organ damage.

Recommended exams to diagnose HT are summarized in Table 3.

Recommended exams29,31

| Recommended exams for all hypertensive patients |

|---|

| • Basic laboratory evaluation;• Serum potassium and sodium;• Serum uric acid;• Urine analysis: microscopic examination, proteinuria by dipstick test, microalbuminuria test;• 12-lead ECG;• Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, if available, for diagnosis and treatment surveillance. |

| Recommended exams in specific populations for TOD research | |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray | Clinical suspicion of cardiac and/or pulmonary involvementDilation or aortic aneurysm (if TTE not available)Suspected coarctation of the aorta |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) | Signs of LVH on ECG or in patients with clinical suspicion of HF |

| Albuminuria | Hypertensive patients with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or with two or more RFNormal values <30 mg/24 h |

| Carotid echo/doppler | Carotid murmur, signs of cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerotic disease in other areas.IMT values >0.9 mm and/or atherosclerotic plaques |

| Renal echo/doppler | Patients with abdominal masses or abdominal murmur |

ECG: electrocardiogram; HF: heart failure; IMT: Intima-media thickness; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; RF: risk factors; TOD: target organ damage; TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram.

A suggested treatment algorithm for HT is presented in Figure 2.

Suggested therapeutic regimen for the management of hypertension.31aCKD is defined as eGFR<60 ml/min/1.72 m2 with or without proteinuria; bpreferential use of loop diuretics if eGFR<30 ml/min/1.72 m2, due to thiazide diuretics or similar being much less effective when eGFR is reduced to these levels; ccaution: risk of hyperkalemia with spironolactone, especially when eGFR is less than 45 ml/min/1.72 m2 or when basal kalemia ≥4.5 mmol/L. ACEi: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; BP: blood pressure; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CKD: chronic kidney disease; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF: heart failure.

- •

18–65 years:

- ∘

Initial goal: blood pressure (BP) <140/90 mmHg;

- ∘

If well tolerated, SBP should be between 120–130 mmHg and DBP between 70–79 mmHg;

- •

>65 years:

- ∘

SBP 130–140 mmHg and DBP 70–79 mmHg, regardless of CVD history.

- •

Refractory HT (uncontrolled, with SBP>140 mmHg and/or DBP>90 mmHg, despite treatment with three antihypertensives from different drug classes at maximum tolerated doses, one of which is a diuretic);

- •

HT in young patients (<35 years);

- •

White coat HT and masked according to clinical judgment, of high and very high cardiovascular risk according to SCORE and for diagnostic clarification;

- •

Suspected secondary HT, according to the following criteria:

- ∘

Young patients (<40 years) with grade 2 HT or onset of any degree of HT in childhood;

- ∘

Acute worsening of the BP profile in patients, complying with therapy, with previously documented stable normotension or severe HT (grade 3) or hypertensive emergency;

- ∘

Refractory HT;

- ∘

Presence of relevant target organ damage;

- ∘

Clinical or biochemical characteristics suggestive of endocrine causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or HT (in this context it may be important to also refer to the respective medical specialties);

- ∘

Clinical features suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea (excessive daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, observed episodes of interrupted breathing during sleep, abrupt awakenings accompanied by gasping or choking, waking with a dry mouth or sore throat, morning headache, difficulty concentrating during the day);

- ∘

Symptoms suggestive of pheochromocytoma or family history of pheochromocytoma.

- •

Properly controlled BP.

- •

Lifestyle modification (healthy diet and physical activity).

- •

Initial BP reduction in 1–2 weeks, which may continue to decrease over two months.

- •

Initial reassessment in the first month and follow-up dependent on the severity and comorbidities, with a maximum interval of six months (in medical and/or nursing consultation).

- •

Procedures for surveillance in general practice:

- ∘

Demonstrate BP control, compliance and tolerance to treatment;

- ∘

Assess target organ damage;

- ∘

Assess persistence and/or emergence of new cardiovascular risk factors;

- ∘

Reinforce recommendations for lifestyle changes;

- ∘

Regular exams:

- •

Glycemia, lipid profile, uricemia, creatinine, microalbuminuria: annually.

- •

ECG every two years if the previous one is normal.

- •

Potassium: after one month of treatment and annually if the patient is treated with diuretic/ACEi/ARB/spironolactone.

Transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion, characterized by sudden onset of short duration and spontaneous and complete recovery, accompanied by loss of postural tone32;

Presyncope are the signs and symptoms (dizziness, blurred vision, nausea, paleness, warmth, perspiration, others) that precede loss of consciousness in syncope32;

Syncope is very common in the community and 20–50% of the adult population will have at least one syncope throughout life.32

Initial approach to the patient and assessment in primary health careGiven the very different prognosis of the various forms of syncope, an accurate diagnosis is fundamental. After excluding other forms of non-syncope transient loss of consciousness, such as convulsion or psychogenic forms, syncope can be divided into three major etiological groups: reflex, due to orthostatic hypotension, or cardiac.33

Approximately 10–20% of patients may remain without an etiological diagnosis.34 Up to one third of these patients will experience recurrence of syncope.35

Clinical history and physical examinationWith a careful clinical history and physical examination, which should include an orthostatic test (BP measurement in decubitus and orthostatism) and carotid sinus massage in patients over 40 years (usually performed in a hospital setting), up to 85% of all patients may have an etiological diagnosis (see Table 4).33,36

Signs and symptoms suggestive of reflex etiology, orthostatic hypotension or cardiac.33

| Reflex syncope | Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension | Cardiac syncope |

|---|---|---|

| • Long history of recurrent syncope, particularly occurring before 40 years of age;• After unpleasant vision, sound, smell or pain;• Prolonged orthostatism;• During the meal;• To be in crowded and/or hot places;• Autonomic activation before syncope: paleness, perspiration and/or nausea/vomiting;• With rotation of the head or pressure in the carotid sinus (such as in tumors, shaving, tight collars);• Absence of heart disease. | • While or after standing;• Prolonged orthostatism;• Standing after exertion;• Postprandial hypotension;• Temporal relationship with onset or alteration of the dosage of vasodepressor or diuretic drugs leading to hypotension;• Presence of autonomic neuropathy or Parkinson's disease. | • During exertion or in supine position;• Palpitations of sudden onset immediately followed by syncope;• Family history of unexplained sudden death at an early age;• Presence of structural heart disease (left ventricular dysfunction; moderate or severe valvular disease; cardiomyopathies; pulmonary hypertension);• Presence of coronary artery disease.ECG findings suggestive of arrhythmic syncope:• Bifascicular block (defined as left or right BBB combined with left anterior or posterior fascicular block);• Other intraventricular conduction anomalies (QRS duration ≥0.12 s);• Mobitz I second degree atrio-ventricular (AV) block and 1st degree AV block with markedly prolonged PR interval;• Mild asymptomatic inadequate sinus bradycardia (40-50 bpm) or slow AF (40-50 bpm) in the absence of negative chronotropic drugs;• Non-sustained VT;• Pre-excited QRS complexes (Wolff-Parkinson-White);• Long or short QT intervals;• Early repolarization;• Elevation of the ST segment with type 1 morphology on the V1-V3 leads (Brugada pattern);• Negative T waves on the right precordial leads, epsilon waves suggestive of arrhythmogenic right ventricle dysplasia;• Left ventricular hypertrophy suggesting hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.TTE findings suggestive of cardiac syncope (non-exhaustive list):• Obstructive valvular disease;• Cardiomyopathy pattern;• Left or right ventricular dysfunction;• Pulmonary hypertension;• Changes in segmental kinetics suggestive of ischemia. |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AV: atrio-ventricular; BBB: bundle branch block; ECG: electrocardiogram; VT: ventricular tachycardia.

In the context of PHC, the approach in terms of initial diagnostic exams will include:33

- ∘

Basic laboratory evaluation;

- ∘

ECG;

- ∘

24 h Holter;

- ∘

TTE with Doppler study, particularly in the presence of known previous heart disease or when there are data suggestive of structural heart disease or cardiac syncope (see Table 4);

- ∘

Stress test, if there are complaints of angina or syncope on exertion (preferably performed in a hospital setting).

Dizziness is also common. It is a heterogeneous symptom, including feeling dizzy (sense of motion, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, paleness and diaphoresis), presyncope (perception of an imminent episode of fainting accompanied by paleness, diaphoresis and nausea) and imbalance (loss of balance without feeling of movement).37 The most frequent causes include peripheral vertigo, labyrinthitis, Menière disease, central vestibular causes, psychiatric diseases, hyperventilation and multifactorial causes. The prognosis of dizziness is usually favorable, unlike that of cardiac syncope.37

When to refer to cardiologyReferral criteria (cardiology consultation)- •

Syncope suggestive of cardiac etiology:

- ∘

Based on clinical criteria or after suggestive findings in diagnostic exams available in PHC (ECG, TTE, stress test, laboratory tests) (see Table 4);

- •

Recurrent syncope, even if of unlikely cardiac etiology;

- •

Syncope in patients with pacemakers or other devices;

- •

Syncope of unlikely cardiac etiology, but in patients with high risk professions (heavy-duty drivers, divers, etc.).

- •

Syncope and33:

- ∘

Documented 2nd or 3rd degree AV block (ECG or Holter);

- ∘

Documented alternating branch block (ECG or Holter);

- ∘

Trifascicular block (ECG or Holter);

- ∘

Severe aortic stenosis;

- ∘

Severe depression of left ventricular function;

- ∘

Severe pulmonary HT;

- ∘

ICD shock;

- ∘

Suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS);

- ∘

Suspected pulmonary thromboembolism;

- ∘

Suspected dissection of the aorta;

- ∘

Traumatic brain injury.

After evaluation in an external hospital consultation (often involving neurology and psychiatry), a final diagnosis is normally achieved in approximately 80% of patients, and this will determine the therapeutic approach.38

Criteria for return to primary healthcare33- •

Cardiac syncope:

- ∘

Treated with implantable devices (follow-up at devices consultation);

- ∘

Treated by ablation, surgery or pharmacological control (may be discharged or followed-up in a specific consultation, depending on the situation, but only after a period of at least one year without symptoms).

- •

Syncope of unknown etiology with implanted event recording device (follow-up at device consultation);

- •

Reflex syncope without indication for pacemaker implantation and with clinical improvement after the establishment of general and/or pharmacological measures;

- •

Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension and with clinical improvement after the establishment of general and/or pharmacological measures.

- •

The therapeutic approach to most patients with syncope of non-cardiac etiology (reflex or due to orthostatic hypotension) involves reassurance, general measures and adjustment of established therapy;

- •

The follow-up is based on the evaluation of the response to these measures over time;

- •

Patients with syncope of non-cardiac etiology (reflex or due to orthostatic hypotension) or of unknown etiology may have syncope recurrences;

- ∘

In these cases, the approach is summarized in Table 5. Some of the approaches can be addressed in PHC.

Table 5.Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of syncope.33

Reflex syncope Education, lifestyle changes and reassurance as to the benign nature of this condition Severe/recurrent type Low BP phenotypeYounger patients• Fludrocortisone• Midodrine ProdromesYounger patients: Counter-pressure maneuvers; Orthostatic training Hypotensive drugsYounger and younger or older patientsSuspend/reduce hypotensive drugs Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension Education, lifestyle changes, hydration, and adequate saline intake Suspend/reduce vasoactive drugs If symptoms persist: a. Counter-pressure maneuvers (cross legs or hands or press with arms);b. Elastic compression stockings;c. Sleeping with raised headboard;d. Anti-hypertensives (ACEi, ARB, CCB) should be carefully used, especially in patients at high risk of falls;e. Midodrine (2.5–10 mg, tid);f. Fludrocortisone (0.1–0.3 mg od). ACEi: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker; Od: daily; Tid: three times a day.

- •

Patients with recurrent syncope despite the initial approach or who have begun high risk professions should be re-referred for consultation.

The definition and the main points in the diagnosis of valve diseases, as well as the referral criteria and follow-up plan are presented in Table 6.

Definition, diagnosis, referral criteria and follow-up plan in primary health care.59-63

| Valve diseases | Definition & diagnosis | Referral criteria | Follow-up plan in PHC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic valve disease | |||||

| Aortic Stenosis (AS) | Systolic opening restriction due to degenerative disease (majority). In younger patients resulting from bicuspid aortic valve.Diagnosis:Natriuretic Peptides (if possible);Mode M and 2D and Doppler TTE:• Mild: Vmax>2.5 m/s or mean ΔP<20 mmHg; valvular area>1.5cm2; aortic VTI LVOT/VTI ratio >0.5• Moderate: Vmax 3.0–3.9 m/s or ΔP 20–39 mmHg; valvular area >1.0–1.5 cm2; aortic VTI LVOT/VTI ratio=0.25-0.5• Severe: Vmax≥4m/s or ΔP≥40mmHg; valvular area: ≤0.1 cm2; aortic VTI LVOT/VTI ratio <0.25 | i) Patients with severe ASii) Patients with moderate AS, symptomatic or with systolic dysfunction | Echocardiographic control:Progressive lesion• Mild AS: 3–5 years;• Moderate AS: 1–2 years.Patients with severe AS will be followed-up at the hospital. | ||

| Aortic Regurgitation (AR) | Primary disease of the aortic valve cusps and/or anomalies of the aortic root and ascending aortic geometry. The primary causes of AR in adults are: degeneration of the aortic valve or root (with or without a bicuspid valve); rheumatic fever; infectious endocarditis; myxomatous degeneration; thoracic aortic aneurysm. In children, the most common cause is ventricular septal defect with aortic valve prolapse.Diagnosis:TTE:• Mild AR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: Vena contracta width (VCW) <3 mm, PHT >500 ms;∘ Quantitative methods: EROA <10 mm2, regurgitant volume <30 ml;• Moderate AR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW ≥3-<6 mm, PHT ≥200-≤500 ms;∘ Quantitative methods:·Mild to moderate AR: EROA 10-19 mm2, regurgitant volume 30-44 ml;·Moderate to severe AR: EROA 20-29 mm2, regurgitant volume 45-59 ml;• Severe AR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW ≥6 mm, PHT <200 ms;∘ Quantitative methods: EROA ≥30 mm2, regurgitant volume ≥60 ml; | i) Documented severe AR in symptomatic and non-symptomatic patients;ii) Patients with moderate AR and LV dilation;iii) Patients with severe dilation of the aortic root;iv) Patients with Marfan syndrome with aortics root disease;v) Patients with aortic bicuspid;vi) Collagen diseases. | Echocardiographic control:Progressive lesion• Mild AR: 3–5 years;• Moderate AR: 1–2 years.Patients with severe AR will be followed-up at the hospital. | ||

| Mitral valve disease | |||||

| Mitral Stenosis (MS) | Thickening and calcification of the mitral valve, resulting in blood flow restriction from the left atrium to the left ventricle due to a narrowed mitral passage.Mitral stenosis usually results from rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever occurs mainly in children following streptococcal pharyngitis or scarlet fever. In the elderly, it occurs mainly if they had rheumatic fever and did not undergo antibiotic therapy during their youth.Diagnosis:TTE:• Mild MS: mitral valve area (MVA) >1.5 cm2, mean gradient <5 mmHg, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) <30 mmHg;• Moderate MS: MVA 1.0-1.5 cm2, mean gradient 5-10 mmHg, PAP 30-50 mmHg;• Severe MS: MVA <1.0 cm2, mean gradient >10 mmHg, PAP >50 mmHg; | i) Symptomatic and non-symptomatic patients with moderate/severe MS; | Echocardiographic control:Progressive lesion3–5 years (MVA > 1.5 cm2).Patients with significant MS (MVA<1.5 cm2) will be followed-up at the hospital. | ||

| Mitral Regurgitation (MR) | It is essential to distinguish primary from secondary MR. In primary MR, one or several components of the mitral valve apparatus are directly affected.Secondary MR may be of the atrial (secondary to atrial dilation – frequent in HFpEF) or ventricular (frequent in HFrEF) type.Diagnosis:TTE• Mild MR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW <3 mm;∘ Quantitative methods: EROA <20 mm2, regurgitant volume <30 ml;• Moderate MR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW ≥3-<7 mm;∘ Quantitative methods:· Mild to moderate MR: EROA 20-29 mm2, regurgitant volume 30-44 ml;· Moderate to severe MR: EROA 30-39 mm2, regurgitant volume 45-59 ml;• Severe MR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW ≥7 mm;∘ Quantitative methods: EROA ≥40 mm2, regurgitant volume ≥60 ml. | i) Patients with severe MR;ii) Patients with moderate MR with LV dilatation or systolic dysfunction,, pulmonary hypertension or heart failure. | Echocardiographic control:Progressive lesion• Mild: 3–5 years;• Moderate: 1–2 years.Patients with severe MR will be followed-up at the hospital. | ||

| Tricuspid valve disease | |||||

| Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) | Pathological TR is most commonly secondary and due to right ventricle dysfunction following pressure and/or volume overload in the presence of structurally normal leaflets. The most frequent causes are: infectious endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid syndrome, myxomatous disease, endomyocardial fibrosis, Ebstein's disease and congenitally dysplastic valves, drug-induced valve diseases, chest trauma, and iatrogenic valve injury.Diagnosis:TTE• Mild TR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW not defined; PISA≤5 mm;∘ Quantitative methods:· Not defined;• Moderate TR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW <7 mm, PISA 6-9 mm;∘ Quantitative methods:· Not defined;• Severe TR:∘ Semi-quantitative methods: VCW > 7 mm, PISA >9 mm;∘ Quantitative methods: EROA ≥40 mm2, regurgitant volume≥45 ml. | Patients with severe TR;Patients with moderate isolated TR with right ventricular dilation with symptoms of heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. | Echocardiographic control:Progressive lesion• Mild: 3–5 years;• Moderate: 1–2 years.Patients with severe TR will be followed-up at the hospital. | ||

| Valve prostheses | |||||

| Mechanical and biological valve prostheses | In adults, the choice between a mechanical and biological valve is mainly determined by the risk of bleeding related to anticoagulation and the risk of thromboembolism when using a mechanical valve versus the risk of structural deterioration of the bioprosthesis, with lifestyle and patient's preferences being also considered. | i) Patients with prosthesis with de novo onset of cardiac symptoms (heart failure, angor, syncope);ii) Evidence of prosthesis dysfunction in TTE. | Echocardiographic control:1. Mechanical valve (surgical) – baseline;2. Bioprosthesis (surgical) – baseline; 5–10 after surgery; and then annually;3. Bioprosthesis (transcatheter) – baseline and annually thereafter;4. Mitral valve repair (surgical) – baseline; 1 year; and 2–3 years thereafter;5. Mitral valve repair (transcatheter) – baseline and then annually;6. Bicuspid aortic valve disease – Post-AVR monitoring of aortic diameter if aortic diameter ≥4.0 cm at the time of AVR. | ||

| Mechanical and biological valve prostheses | Antithrombotic theraphy:It is recommended to follow the regimen suggested by the surgical team;INR control: | ||||

| Thrombogenicity of the prosthesis | Risk factors (RF)(tricuspid or mitral valve replacement, previous venous thromboembolism, AF, mitral stenosis of any degree, LVEF <35%) | ||||

| None | ≥1 RF | ||||

| Low | 2.5 | 3.0 | |||

| Average | 3.0 | 3.5 | |||

| High | 3.5 | 4.0 | |||

| Prophylaxis of endocarditis:Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in high risk procedures in patients with valve prostheses, including percutaneous valves or valves repaired with prosthetic material, and in patients with previous episodes of infectious endocarditis.High risk procedures (for which antibiotic prophylaxis of endocarditis is recommended) are:• Dental procedures that require perforation of the oral mucosa or gingival or periapical manipulation;• Invasive procedures in an infectious context of respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, or dermatological tracts. | |||||

AS: aortic stenosis; AR: aortic regurgitation; AVR: Aortic valve replacement; EROA: Effective regurgitant orifice area; HFrEF/p: Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction/preserved; INR: International normalized ratio; LV: left ventricular; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT VTI: left ventricular outflow tract velocity-time integral; MR: mitral regurgitation; MS: mitral stenosis; MVA: Mitral valve area; PAP: Pulmonary arterial pressure; PHT: Pressure halftime; PISA: proximal isovelocity surface area; PT: Pulmonary thromboembolism; RF: Risk factors (previous PT and VT; recent surgery or immobilization; neoplasm; heart rate>100 bpm); TR: tricuspid regurgitation; TTE: Transthoracic echocardiogram; VCW: Vena contracta width; VKA: Vitamin K antagonist; VT: Venous thromboembolism; VTI: velocity-time integral.

Atherosclerotic CAD is a chronic progressive disease associated with a continuous high risk of long-term cardiovascular events.39 The risk of instability increases with insufficient control of cardiovascular risk factors, suboptimal lifestyle modifications, poor adherence to medical therapy or the presence of large areas of myocardial ischemia.39,40

DiagnosisEvaluating signs and symptoms41,42- •

Typical angina: presence of the three characteristics:

- ∘

chest pain or discomfort (feels like pressure or squeezing);

- ∘

precipitated by physical exertion;

- ∘

relieved at rest or with nitrates.

- •

Atypical angina: presence of two of the previous characteristics;

- •

Non-anginous chest pain: presence of one or none of the previous characteristics;

- •

Assess: precipitating factors (severe anemia, poorly controlled HT, dysrhythmias, hyperthyroidism, smoking or contraceptive use), atherosclerotic disease in other territories (cerebral, carotid and lower limbs) and erectile dysfunction.

- •

Basic laboratory evaluation;

- •

ECG at rest;

- •

Chest X-ray (symptoms of heart failure or lung disease);

- •

TTE.

- •

When CAD is suspected, determine the pre-test probability (PTP). PTPs of CAD according to age and to nature of symptoms are presented in Table 7;

Table 7.Pre-test probability of coronary artery disease.42

Higher probability is indicated by darker shades of blue.

- •

In patients with low PTP (5–15%), the presence of other determinants of increased risk, such as cardiovascular risk factors, changes in ECG at rest, left ventricular dysfunction, abnormal stress test and coronary calcification should be considered.

First-line exams in patients with intermediate probability (PTP>15%):

- I.

Non-invasive functional imaging for the determination of ischemia:

- •

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS);

- •

Stress TTE.

- II.

Anatomical evaluation with computed tomography coronary angiogram (CTCA)

The stress test has a low performance in the confirmation or exclusion of the disease.

In the case of high clinical probability of CAD, persistence of symptoms under medical therapy, typical angina at low level of exertion or high risk of cardiovascular events – invasive coronary angiography may be indicated (refer to urgent cardiology consultation).

Action plan in primary health careNon-pharmacological measures44:- •

Lifestyle modification and aggressive control of all cardiovascular risk factors.

- •

Anti-angina therapy:

- ∘

1st line: BB at maximum tolerated dose (MTD);

- ∘

2nd line: CCB, ivabradine, nicorandil, ranolazine, trimetazidine and long-acting nitrates (nitroglycerin, isosorbide dinitrate and isosorbide mononitrate).

- •

Antithrombotic therapy:

- ∘

Before hospital referral:

- •

If ischemia was unequivocally demonstrated and the patient has an appropriate clinical risk profile, aspirin can be started;

- ∘

After elective angioplasty:

- •

Aspirin (ASA) 100 and clopidogrel 75 for at least 6 months; in case of high hemorrhagic risk: 1–3 months;

- ∘

After acute coronary syndrome:

- •

Dual antiplatelet therapy (ASA+ticagrelor 90 mg or prasugrel 10 mg; if unavailable or contraindicated, clopidogrel);

- •

For at least 12 months;

- •

Long-term extension with ticagrelor 60 mg in patients at high (IIa) or moderate (IIb) risk of ischemic events: diffuse multivessel CAD associated with comorbidities (diabetes, recurrent myocardial infarction (MI), peripheral artery disease, or CKD), without high hemorrhagic risk and who tolerate dual antiplatelet therapy during the first year;

- •

Alternatively to DAPT, may consider intensification with rivaroxaban 2.5 mg therapy in combination with aspirin in patients who had an myocardial infarction at least one year before or in cases of CCS with multivessel CAD;

- •

In patients with indication for long-term oral anticoagulation therapy (AF):

- ∘

Hospitalization: Aspirin+clopidogrel+anticoagulant;

- ∘

First year: Clopidogrel+oral anticoagulant (direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC));

- ∘

>12 months: oral anticoagulant (DOAC).

- •

Hypolipemic therapy:

- ∘

Therapeutic goals:

- •

LDL-c<55 mg/dL and reduction of at least 50% relative to baseline;

- •

In the presence of second event within two years: LDL-c<40 mg/dL;

- ∘

Recommended drugs: statins at MTD, ezetimibe and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) (available at hospital level)

- •

Antihypertensive therapy:

- ∘

Therapeutic goal: BP<130 mmHg, if tolerated;

- ∘

Recommended drugs: BB and/or ACEi; if necessary add other drugs;

- •

Antidiabetic therapy:

- ∘

1st line: SGLT2i and GLP-1 analogues, due to their impact on the reduction of CV events.

- •

Suspected ACS;

- •

Initial clinical evaluation suggestive of high risk events:

- ∘

High clinical probability of CAD;

- ∘

Persistence of symptoms under optimized medical therapy;

- ∘

Typical angina at low level of exertion (in the context of daily life activities);

- ∘

Carotid disease or symptomatic peripheral artery disease in patients with ischemic cardiopathy;

- •

Significant de novo ischemia (MPS with ischemic area ≥10% of the myocardium);

- •

Significant lesions in CTCA (CAD RADS >3: severe coronary stenosis [70-99%)], left main >50% or 3-vessel obstructive [≥70%] disease, total coronary occlusion [100%]).

- •

Left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF<50%).

- •

Signs, symptoms, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities;

- •

Results of exams;

- •

Response to established therapy.

Patients with controlled cardiovascular symptoms and risk factors after diagnosis and therapeutic optimization by a cardiologist.

Follow-upAfter initial diagnosis or CV event, consultation at three and six months, annually thereafter42:

- •

Clinical evaluation, lifestyle modification, cardiovascular RF control and adherence to therapy;

- •

Routine exams:

- •

Basic laboratory evaluation;

- •

ECG at rest;

- •

TTE: 1 year (if previously abnormal) or periodically (every 3–5 years);

- •

Non-invasive imaging exam: change in the level of symptoms or periodically (every 3-5 years) for ischemia assessment.

Bradycardia is characterized by a HR <60 bpm and can be caused by a dysfunction in the sinus node, an atrioventricular block or a block in conduction. Tachycardia is characterized by a HR >100 bpm and can be ventricular or supraventricular.

Palpitations result from an unconfortable perception of the heartbeat by the patient. Two types of palpitations are identified:

- •

Normal palpitations – they occur due to exercise, emotion, stress, or after ingestion of substances that increase adrenergic activity or decrease vagal activity;

- •

Abnormal palpitations – they occur for no reason and can be fast or strong/slow. These palpitations may indicate cardiac arrhythmia. However, most people who have electrical conduction disturbances experience syncope, and chest pain, rather than palpitations.45–49

- •

Baseline laboratory assessment plus evaluation of the thyroid function and of potassium and magnesium levels50;

- •

Immediate electrocardiographic monitoring if arrhythmic syncope is suspected.50,51

- •

If there is known previous heart disease or when data are suggestive of structural and functional left ventricular (LV) heart disease.50,53

- •

Bradycardia: the dose of drugs that may be inducing bradycardia should be adjusted and secondary causes, such as hypothyroidism, should be excluded.48

- •

In the context of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, antiarrhythmic drugs may play an important role in their control, particularly in atrial fibrillation (AF) and in some specific arrhythmias.48,50

- •

With the exception of BB, currently available antiarrhythmic drugs are not effective in the primary treatment of patients with potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias or in preventing sudden cardiac death. Each drug has significant potential to cause adverse events, including pro-arrhythmia.50

- •

Ventricular or supraventicular extrasystole:

- ∘

Evidence of cardiopathy associated with systolic LV dysfunction, myocardial ischemia, valve pathology, or cardiomyopathies;

- ∘

Typical ECG abnormalities (Wolff-Parkison-White, long QT, Brugada);

- ∘

Intense associated symptomatology;

- ∘

Complex or frequent ventricular premature beats (>5000 EVs/24 h);

- ∘

Supraventricular premature beats (≥10/hour) in patients who remain symptomatic after a first therapeutic approach with a beta-blocker or at risk of developing AF.

- •

Bradycardia:

- ∘

In the context of syncope (see syncope's chapter);

- ∘

When associated with dizziness or tiredness;

- ∘

Patients with pacemakers – for regular follow-up (if they have missed the follow-up at device consultation).

- •

Supraventricular tachycardias:

- ∘

Documented and maintained supraventricular paroxysmal tachycardia;

- ∘

If associated with the presence of Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern;

- ∘

Atria flutter or AF (see AF's chapter).

- •

Ventricular tachycardias on Holter:

- ∘

Sustained ventricular tachycardias (>30 seconds or symptomatic) – refer to the emergency department;

- ∘

Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, even if asymptomatic, if:

- •

Typical ECG abnormalities (Wolff-Parkison-White, long QT, Brugada).

- •

Cardiac structural changes (depressed function, CAD, valve disease, myocardiopathy, family history of sudden death).

- •

Palpitations:

- ∘

Patients with frequent or persistent palpitations;

- ∘

Sustained rapid palpitations;

- ∘

Significant associated symptoms:

- •

Pre-syncope/syncope (consider the situation context);

- •

Shortness of breath;

- •

Chest pain;

- ∘

Family history of recurrent syncope or sudden death;

- ∘

ECG or echocardiographic anomalies (see above).

Follow-up will depend on the type of arrhythmia, whether there is concomitant hospital follow-up, whether a device has been implanted (which requires specific follow-up), or whether an antiarrhythmic drug has been prescribed.50

Atrial fibrillationDefinitionSupraventricular arrhythmia, characterized by irregular RR intervals and absence of P-wave on ECG (duration>30 s).54

Evaluation of the patient with atrial fibrillation in primary health care- •

Clinical history, comorbidities, AF pattern, thromboembolic risk, symptoms55;

- •

Modified European Heart Rhythm Association scale of symptoms (Table 8)56;

Table 8.Modified European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) scale of symptoms.56

Modified European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) scale of symptoms Modified EHRA score Symptoms Description 1 None AF does not cause any symptoms 2a Mild Normal daily activity is unaffected by AF-related symptoms 2b Moderate Normal daily activity is unaffected by AF-related symptoms, but the patient suffers from the symptoms 3 Severe Normal daily activity affected by AF-related symptoms 4 Incapacitating Normal daily activity discontinued AF: Atrial Fibrillation; EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

- •

12-lead ECG54;

- •

Baseline laboratory evaluation plus ionogram and thyroid hormone levels54;

- •

TTE: assessment of left atrium dimensions, structural cardiopathy;54

- •

Holter54;

- •

Non-invasive ischemia test (MPS, coronary angio-CT) – in patients with suspected CAD54;

- •

Brain CT – in patients with suspected stroke.54

- •

Paroxysmal AF: ends spontaneously or with intervention up to seven days;

- •

Persistent AF: AF lasting >7 days, including episodes terminated by electrical or pharmacological cardioversion;

- •

Long-term persistent AF: continuous AF with duration ≥1 year, subject to rhythm control strategy;

- •

Permanent AF: long-term continuous AF under heart rate control strategy (where the possibility of conversion to sinus rhythm is excluded).

- •

A - Anticoagulation

- i.

Stroke risk assessment, according to Table 957

Table 9.Risk factors and respective CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores.64,65

CHA2DS2-VASc score CHA2DS2-VASc risk factors Score Congestive heart failureSigns/symptoms of heart failure or objective evidence of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction +1 HypertensionBP at rest >140/90 mmHg on at least two occasions or ongoing antihypertensive treatment +1 Age: 75 years or older +2 DiabetesmellitusFasting glucose > 125 mg/dL or treatment with oral hypoglycemic agent and/or insulin +1 Previous stroke, transient ischemic accident, or thromboembolism +2 Vascular diseasePrevious myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque +1 Age: 65–74 years +1 Gender: women +1 HAS-BLED score HAS-BLED risk factors Score Uncontrolled hypertensionSBP>160 mmHg +1 Altered renal and/or hepatic functionDialysis, transplant, serum creatinine>2.26 mg/dL, cirrhosis, bilirubin>2x reference limit value, AST/ALT/ALP>3x reference limit value 1 point per each StrokePrevious ischemic or hemorrhagic strokea +1 Previous history of bleeding or predisposition to bleedingMajor previous hemorrhage or anemia or severe thrombocytopenia +1 Labile INRbTTR (Time in therapeutic range)<60% in patients under VKA +1 ElderlyAge>65 years or extreme frailty +1 Concomitant consumption of drugs/alcoholConcomitant consumption of antiplatelet agents or NSAID; and/or excessive alcohol consumptionc 1 point per each (a) in the presence of previous hemorrhagic stroke, the next criterion related to previous hemorrhage should also be scored;

(b) only relevant if the patient is under VKA;

(c) excessive alcohol consumption refers to an excessive intake (i.e. >14 units per week), in a situation where the clinician considers that there may be an impact on health or bleeding risk.

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BP: blood pressure; INR: international normalized ratio; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TTR: time in therapeutic range; VKA: vitamin K antagonists.

- ∘

CHA2DS2-VASc score 0 in men and 1 in women:

- a.

No indication for antithrombotic therapy;

- ∘

CHA2DS2-VASc=1 in men or =2 in women:

- a.

Oral anticoagulant (OAC) should be considered (IIa);

- ∘

CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 in men or ≥3 in women:

- a.

OAC is recommended (Ia);

- ∘

Identify modifiable hemorrhagic risk factor;

- ∘

HAS-BLED≥3:

- a.

Control all modifiable hemorrhagic RF;

- b.

Regular patient evaluation;

- c.

No reason to discontinue or to not initiate anticoagulation.

- iii.

Treatment selection54

- ∘

DOACs are recommended as 1st line

- ∘

Vitamin K antagonist – as DOAC are contraindicated in patients with:

- a.

Mechanical valve prostheses;

- b.

Moderate-severe mitral stenosis.

- •

B - Symptom control54

- i.

Heart rate control:

- ∘

Evaluation of comorbidities

- a.

None or HT or HFpEF: BB or non-dihydropiridine CCB (verapamil, diltiazem);

- b.

HFrEF: BB;

- c.

Severe COPD or asthma: non-dihydropiridine CCB (verapamil, diltiazem);

- d.

Pre-excited AF/Atrial flutter: ablation.

- ∘

Combination of various drugs, including digoxin and amiodarone;

- ii.

Heart rhythm control:

- ∘

Propafenone (patients without structural cardiopathy); Flecainide may be an alternative after cardiology assessment;

- ∘

Amiodarone (patients with structural cardiopathy);

- ∘

Electrical cardioversion.

- •

C - Control comorbidities and RF54:

- ∘

HT, type 2 diabetes, obesity, sleep apnea syndrome, dyslipidemia, HF, CAD, COPD, severe asthma, advanced age, genetic alterations, physical inactivity, alcohol and tobacco consumption;

- ∘

Aggressive control of risk factors, lifestyle modification;

- ∘

Clinical stabilization of comorbidities.

- •

Patients with indication for rhythm control strategy, unresponsive to pharmacological therapy (for possible electrical cardioversion);

- •

Patients who remain symptomatic under appropriate therapy and with controlled ventricular response;

- •

Patients with hard to control ventricular response (mean heart rate in Holter 24 hours >110 bpm after therapy optimization or bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome);

- •

Patient with mean HR<45/min, documentation of pauses >3.0 seconds during the day, or >4.0 seconds at night;

- •

Symptoms associated with AF: angina, HF, syncope, hypotension;

- •

Structural cardiopathy associated with AF, unable to control in PHC;

- •

Complications associated with treatment:

- ∘

Thromboembolic: major hemorrhage, thromboembolism, international normalized ratio outside therapeutic target.

- ∘

Cardiac arrhythmia: AF with rapid ventricular response, tachycardia, or ventricular fibrillation.

The management of patients with AF should be multidisciplinary with an effective communication between primary and secondary health care. The goals of follow-up for patients with AF in PHC are54,55:

- •

Prevent stoke;

- •

Educate the patient about their condition:

- ∘

Establish goals and/or action plan, management of exacerbations;

- •

Optimize the treatment of symptoms such as heart rate and heart rhythm control;

- •

Control all cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities;

- •

Encourage lifestyle changes:

- ∘

Smoking cessation, weight loss, physical activity;

- •

Promote therapeutic adherence;

- •

Monitor diagnostic exams (according to Table 10).

Table 10.Follow-up of patients with AF.55

Type of treatment Cardiology/General practitioner Primary health care Initial follow-up Evaluation Chronic follow-up Evaluation Basic - - Annual Symptoms+ECG (heart rate) Thromboembolic risk controla VKA According to INR According to INR According to INR INR+CBC every 6 months DOAC 1 month CBC Annual Renal and hepatic function+CBC Heart rate (HR) control CCB or BB 1 month ECG (HR) Every 6 months ECG (HR)+Renal and hepatic function (annual) Rhythm control FlecainidebPropafenone 1 week ECG (HR and QRS) Every 6 months ECG (HR)+Renal (ion) and hepatic function (annual) Sotalols 1 week ECG (HR and QT) Every 6 months ECG (HR and QT)+Annual renal function (ions) Amiodarone Bimonthly (x3) Respiratory function test+Liver function Every 6 months ECG (HR)+Annual chest X-ray+Renal, hepatic and thyroid function BB: beta blockers; CBC: complete blood count; CCB: calcium channel blocker; DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant; ECG: electrocardiogram; HR: heart rate; INR: international normalized ratio; VKA: vitamin K antagonist. (a) In the case of mechanical valve prosthesis and in moderate-severe mitral stenosis DOACs are contra-indicated and vitamin K antagonists are mandatory; (b) the prescriber should consider its utilization taking in account its potential pro-arrhythmia effect.

This document does not contain official guidelines but should be viewed rather as an additional tool for the correct referral of patients. Thus, local validation of these recommendations with the referral hospital and the primary health care network is recommended. Although the references cited are based mainly on guidelines from international scientific societies, this document does not intend to be a summary of those guidelines nor does it aim to replace them. On the contrary, it aims to put these recommendations into perspective, taking into account daily clinical practice, especially considering the limitations of access to diagnostic exams and the particularities of the Portuguese national referral network.

Conflicts of interestRui Baptista has received fees for consultancy services and congress attendance from AstraZeneca, Janssen, Ferrer, Bial, Bayer, Novartis, Servier, Medinfar, Jaba-Recordati, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Bristol Myers-Squibb e Vifor Pharma. Silvia Monteiro has received advisory board participation fees from Astrazeneca, Amgen and Bayer in the areas of chronic coronary syndromes and atrial fibrillation and is a subinvestigator in the clinical trials RE-LY, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48, EMPA-REG OUTCOME, IMPROVE-IT, FOURIER, ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, VESALIUS, CAROLINA and CARMELINA. Sara Gonçalves has received consultant fees from AstraZeneca and Servier and speaker fees from Bial and Novartis. Tiago Maricoto, Jordana Dias, Helena Febra and Victor Gil have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingFinancial support for the preparation of this article was provided by AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca had no role in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.