Childhood offers an excellent window of opportunity to start interventions to promote behavioral changes before unhealthy lifestyles become established, leading to cardiovascular diseases. The goal of this pilot educational project for children is the promotion of healthy lifestyles and cardiovascular health.

MethodsThis project was implemented in 4th grade children and included teacher-led classroom activities, a lesson given by a cardiologist and a practical lesson with dietitians. The teacher received a manual containing information on the topics to be discussed in class with the pupils and the children received a book that addresses cardiovascular risk factors and prevention. The components included were diet (D), physical activity (PA) and human body and heart awareness (BH). At the beginning and at the end of the schoolyear, a questionnaire was applied to the children to assess knowledge (K), attitudes (A) and habits (H) on these topics.

ResultsA total of 73 children from two schools from an urban district public school in Lisbon, in a low to medium income area, participated in the project. Following the intervention, there was a 9.5% increase in the overall KAH score, mainly driven by the PA component (14.5%) followed by the BH component (12.3%). No improvement was observed for component D. The benefits were also more significant in children from a lower income area, suggesting that socioeconomic status is a determinant in the response obtained.

ConclusionsAn educational project for cardiovascular health can be implemented successfully in children aged 9 years, but longer and larger studies are necessary.

A infância é uma janela de oportunidade para o início de intervenções que promovam modificações comportamentais antes que se instalem estilos de vida pouco saudáveis que conduzem às doenças cardiovasculares. O objetivo deste projeto piloto é a promoção de estilos de vida saudáveis e saúde cardiovascular em crianças.

MétodosProjeto implantado no 4.° ano de escolaridade e incluiu atividades em sala de aula orientadas pelo professor, uma aula dada por um cardiologista e uma aula prática por especialistas de nutrição. O professor recebeu um manual contendo informação sobre os vários tópicos e as crianças receberam um livro infantil que aborda os fatores de risco cardiovascular e a prevenção. Os componentes abordados incluem Dieta (D), Atividade Física (AF) e Conhecimento do Corpo Humano e Coração (HC). No início e no fim do ano letivo, as crianças responderam a um questionário para avaliar Conhecimentos (C), Atitudes (A) e Hábitos (H) sobre cada um dos tópicos.

ResultadosParticiparam no projeto 73 crianças de duas escolas de um agrupamento escolar público, urbano, em Lisboa, de um meio socioeconómico médio-baixo. Com a intervenção, verificou-se um aumento do score CAH global de 9,5%, sobretudo pela melhoria do componente de AF (14,5%), seguido pelo componente de HC (12,3%). Sem melhoria no componente D. Os benefícios foram mais significativos nas crianças da escola de baixo rendimento económico, sugerindo que o estado socioeconómico terá impacto na resposta obtida.

ConclusãoUm projeto educacional de literacia para a saúde cardiovascular pode ser implantado com sucesso em crianças com 9 anos.

In Europe, cerebral and cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death, representing 46% of all causes of death in women and 38% in men.1 Compared to other countries, both the prevalence and mortality of heart diseases in Portugal is lower.1 Nevertheless, it still represented 30% of all causes of death in 2018.2,3 Furthermore, the impact on the National Health Service is also of relevance, because there are more than 12000 annual admissions due to acute myocardial infarction, more than 18000 admissions due to heart failure and more that 28000 admissions due to stroke.3 There was a clear decrease in mortality in the last decades, due to improvement in treatment and preventive measures. Unfortunately, this trend has decelerated in the last few years.2,3

Regular physical activity, healthy diet and no smoking are essential for the prevention of many non-transmissible diseases, such as cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases, which are responsible for three-quarters of all deaths worldwide and 87% of deaths in Portugal.1,2,4 In 2019, 29.6% and 12.0% of Portuguese children were overweight and obese, respectively, particularly in males and increasing with age.5 Nevertheless, between 2008 and 2019 there was an overall 22% decrease.5 Data on the prevalence of sedentary behavior in Portugal showed very disappointing results, particularly in the 11–17 age groups, with 78% of boys and 91% of girls not complying with the recommendations for physical activity.6 Although there has been an improvement in the percentage of adolescents of school age that practice physical activity more than three times a week (43.1–55.7%), still two out of 10 never engage in any regular sport activity.6 In 2019, 38.4% of students between the age of 13 and 18 years, confirmed having used smoking products (6.1% at 13 years, and 51.3% at 18 years).7 Between 2003 and 2019, the use of traditional smoking products tended to decrease, with a steeper decrease in the younger groups (being 29.4% in 2003 at the age of 13 years).7 In addition, 14.9% started smoking cigarettes and 6.9% electronic cigarettes below the age of 13 years.7 Furthermore, in students aged 15–16 years, only 81% had a perception of the high-risk associated with daily smoking of one or more packs, but only 18% had the same perception for occasional smoking.7

Most cardiovascular risk factors are modifiable by changes in behavior. Adoption of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors begins in early childhood and cardiovascular markers, such as dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, impaired glucose tolerance, obesity and metabolic syndrome can set in as early as three years of age, increasing the risk of development of atherosclerosis in adolescence and early adulthood.8 This complex unhealthy behavioral framework during childhood determines lifestyle patterns as adults and this early period is dominated by behavioral learning.9 Therefore, childhood is an excellent window of opportunity to implement preventive strategies to promote life-long healthy lifestyles, and school is probably the most appropriate choice for this type of intervention.

Previous school-based projects and interventions have been performed in other countries. Probably the most well-known project is being led by Valentin Fuste and is currently ongoing in Spain, Colombia, and the United States of America. The SI! Program (Salud Integral – Comprehensive Health) is a multilevel multicomponent educational intervention, tested in randomized control trials, with long-term follow-up.10 As a long-term intervention, the SI! Program was designed to cover the entire compulsory education in Spain (3–16 years old) from kindergarten to secondary school.10 Its content aligns with the school curriculum, adapted to each educational stage from preschool to secondary school, exploring the health-related content of the standard curriculum in greater detail, with a focus on cardiovascular health.10 Briefly, the SI! Program includes four components coordinated in a multidimensional approach: diet, physical activity, human body and heart awareness, and emotion management.10 This educational strategy showed a promising result in preschool children from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Of note is physical activity, which is the main driver for this improvement, with a beneficial effect on adiposity.11–14 Subsequent randomized trials are underway in older children.15–19

The Portuguese Society of Cardiology implemented a pilot project named “O meu coração bate saudável” in collaboration with the Portuguese Heart Foundation and the Nutrition Department from NOVA Medical School in Lisbon during 2022/2023 academic year. The goal of the project was the promotion of healthy lifestyles and cardiovascular health in school children.

MethodsWe applied this pilot project to the 4th year grade of public elementary school, so the content would align with the scholar curriculum at this educational stage (“Estudo do Meio” class). The intervention included three components coordinated in a multidimensional approach: diet (D), physical activity (PA), and human body and heart awareness (BH). Through components D and PA, children learn how a well-balanced diet and an active lifestyle are directly connected to a healthy heart. The BH component helps the children to understand how the body works and how it is affected by behavior and lifestyle, including smoking. For that objective, there were teacher-led classroom activities, that also included some health challenges (e.g., games, experimental activities, stories). It also included a lesson about the main topics, delivered by a cardiologist, and a practical lesson about diet and nutrition delivered by dietitians from NOVA Medical School, with previous experience in teaching children. To guide the project, teachers were provided with a teacher's manual, developed by the project team, that included basic concepts about the three interventional components (Figure 1). It includes the goals and concepts to be covered, the central activity in which the children participate, and some games that could be used to improve adherence to activities. In addition, all children received a book (“Tenho o coração sempre a sorrir” [My heart is always smiling]), published by the Portuguese Society of Cardiology in 2021 for the celebration of World Heart Day, from the author Eugénio Mendes Pinto and illustrated by Bolota (Figure 1). It is a story about a small boy with unhealthy habits and how his friends helped him to change his perceptions and habits. A booklet with food recommendations and activities related to healthy eating was also given to children by the dietitians during their practical class.

The project was conducted in three school districts – Montemor-o-Velho, Coimbra Centro, and Marquesa de Alorna (Lisbon). It involved a total of 450 children. To validate the current pilot project, the Marquesa de Alorna school district in Lisbon, was chosen. A questionnaire was delivered to the children from that school district at the beginning of the project and at the end of the school year. We used a previously developed and validated questionnaire from the SI! Program (Salud Integral – Comprehensive Health).16,17 This questionnaire is highly specific for elementary school children and was adapted to the contents of the public elementary education in Spain. Because Portugal has similar characteristics compared to Spain, including educational programs, our version is a translation from the Spanish version. Emotion management questions were not included, because our program does not address that topic. Our 23-item questionnaire included questions developed for the age group 9–13 years of age, and whenever they did not fit the content of our program, other questions were included, from the questionnaire developed for the age group 6–11 years.16,17 This would enable us to ascertain whether knowledge, attitudes, and habits (KAH) acquisition were effective during the project. Therefore, the questionnaire included questions related to the human body and heart awareness (9 items), physical activity (6 items) and nutrition (8 items) (Supplemental Figure 1). The questionnaire was specifically built to score each domain (KAH) and each component (D, PA, BH) plus a composite score (overall KAH). Survey responses were scored on a scale from 0 points (undesirable) to 2 points (desirable).16,17 The overall KAH score was derived from the sum of each overall KAH subdomains (Supplemental Figure 2). As the questionnaires were anonymous, we could not assess detailed information on parental education and income. Therefore, we used the school location as a surrogate for socioeconomic status.

The project was approved by the Portuguese Society of Cardiology Ethics Committee. Participation was conditional on informed consent from teachers and children's parents or legal guardians. Informed consent forms were provided to the teachers, who distributed them to parents, collected the completed forms, and returned them to the project team. Questionnaires were answered anonymously. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were compared by independent samples Student's t-test and mean differences were calculated to compare results before and after intervention. A level of significance α=0.05 was considered. IBM SPSS Statistical software, version 26 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

ResultsA total of two schools from Marquesa de Alorna school district in Lisbon participated in this pilot project for specific validation. We included a total of 73 children, from the 4th grade, aged 9 years, 46% males. Both schools are in urban areas. They have facilities for physical activity classes and at least one daily meal (lunch) is provided by the school, in accordance with the Ministry of Education regulations. One of the schools is in a middle income area (school A). The other, is in an area of low to middle income (school B), with major religious and cultural diversity, due to a very diverse parent's background, originating from Brazil and the Portuguese-speaking African countries, Asian countries and from other European countries.

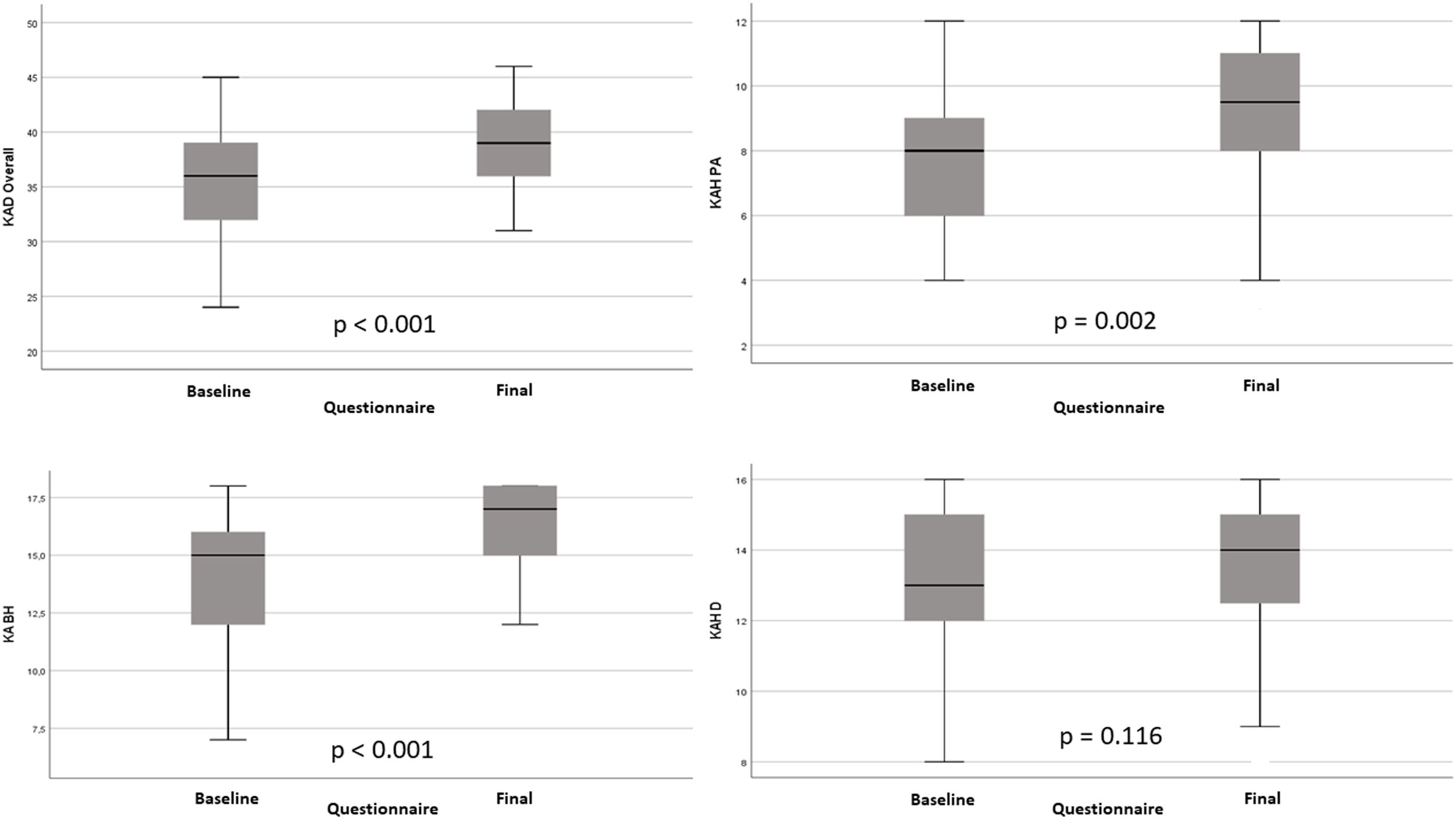

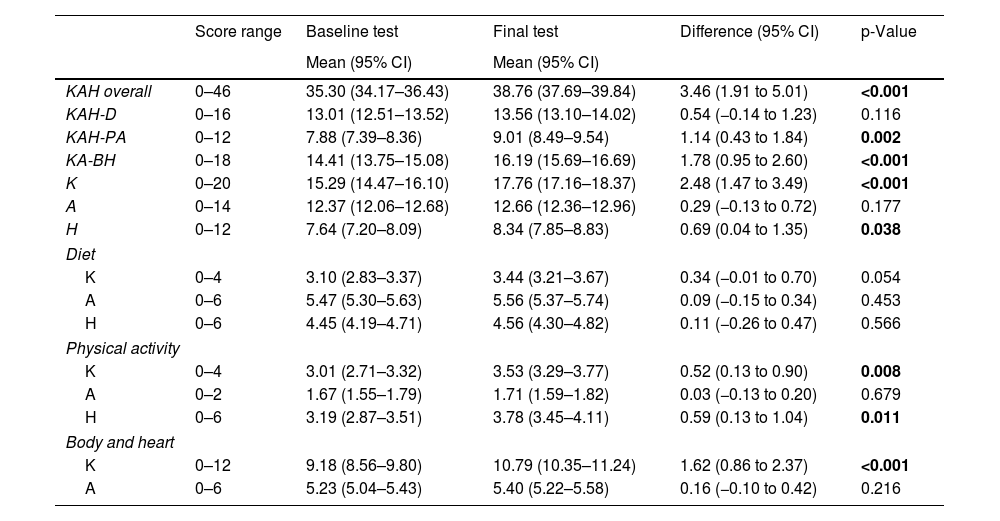

Overall resultsTable 1 and Figure 2 present the differential change from baseline in KAH scores. As expected, the intervention increased the children's overall KAH score (9.8%, p=0.001). The largest differential improvement was observed for the PA component (14.5%, p=0.002), followed by the BH component (12.3%, p<0.001). No significant improvement in the D component was observed, although there was a trend for improvement in the D knowledge domain (10.1%, p=0.054). Overall, the main improvements were observed in the knowledge (16.2%, p<0.001) and habits (9%, p=0.038) domains.

Overall results of the KAH questionnaire, with differences between tests.

| Score range | Baseline test | Final test | Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | ||||

| KAH overall | 0–46 | 35.30 (34.17–36.43) | 38.76 (37.69–39.84) | 3.46 (1.91 to 5.01) | <0.001 |

| KAH-D | 0–16 | 13.01 (12.51–13.52) | 13.56 (13.10–14.02) | 0.54 (−0.14 to 1.23) | 0.116 |

| KAH-PA | 0–12 | 7.88 (7.39–8.36) | 9.01 (8.49–9.54) | 1.14 (0.43 to 1.84) | 0.002 |

| KA-BH | 0–18 | 14.41 (13.75–15.08) | 16.19 (15.69–16.69) | 1.78 (0.95 to 2.60) | <0.001 |

| K | 0–20 | 15.29 (14.47–16.10) | 17.76 (17.16–18.37) | 2.48 (1.47 to 3.49) | <0.001 |

| A | 0–14 | 12.37 (12.06–12.68) | 12.66 (12.36–12.96) | 0.29 (−0.13 to 0.72) | 0.177 |

| H | 0–12 | 7.64 (7.20–8.09) | 8.34 (7.85–8.83) | 0.69 (0.04 to 1.35) | 0.038 |

| Diet | |||||

| K | 0–4 | 3.10 (2.83–3.37) | 3.44 (3.21–3.67) | 0.34 (−0.01 to 0.70) | 0.054 |

| A | 0–6 | 5.47 (5.30–5.63) | 5.56 (5.37–5.74) | 0.09 (−0.15 to 0.34) | 0.453 |

| H | 0–6 | 4.45 (4.19–4.71) | 4.56 (4.30–4.82) | 0.11 (−0.26 to 0.47) | 0.566 |

| Physical activity | |||||

| K | 0–4 | 3.01 (2.71–3.32) | 3.53 (3.29–3.77) | 0.52 (0.13 to 0.90) | 0.008 |

| A | 0–2 | 1.67 (1.55–1.79) | 1.71 (1.59–1.82) | 0.03 (−0.13 to 0.20) | 0.679 |

| H | 0–6 | 3.19 (2.87–3.51) | 3.78 (3.45–4.11) | 0.59 (0.13 to 1.04) | 0.011 |

| Body and heart | |||||

| K | 0–12 | 9.18 (8.56–9.80) | 10.79 (10.35–11.24) | 1.62 (0.86 to 2.37) | <0.001 |

| A | 0–6 | 5.23 (5.04–5.43) | 5.40 (5.22–5.58) | 0.16 (−0.10 to 0.42) | 0.216 |

A: attitude; BH: body and heart; D: diet; H: habitus; K: knowledge; PA: physical activity.

Bold values represent p-values that are significant.

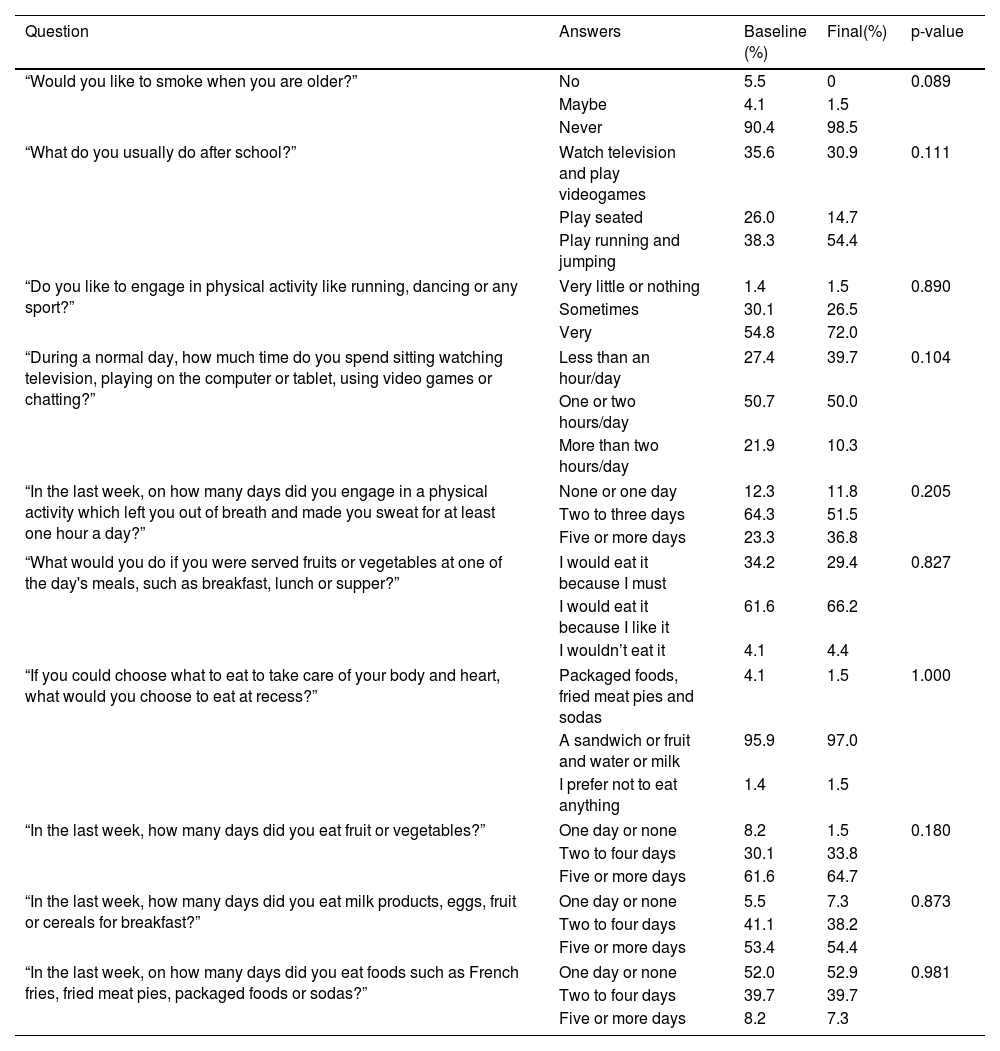

In Table 2 there is a detailed description of the most important attitudes and habits responses in the questionnaire. Although in a direct comparison none are significant, clear trends are identifiable. Compared to baseline, more children think they should never smoke when reaching adulthood, more children are now spending less time in sedentary activities after school and doing more physical activities. Regarding diet, no significant improvement was observed, but more than 60% eat fruit and vegetables five or more days a week, more than 50% eat dairy products, eggs, fruit, and cereals for breakfast five or more days a week. Also of relevance, less than 10% eat foods such as French fries, fried meat pies, packaged food or soda five or more days a week, with more than 50% eating only once a week or not at all.

Change in attitudes and habits.

| Question | Answers | Baseline (%) | Final(%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Would you like to smoke when you are older?” | No | 5.5 | 0 | 0.089 |

| Maybe | 4.1 | 1.5 | ||

| Never | 90.4 | 98.5 | ||

| “What do you usually do after school?” | Watch television and play videogames | 35.6 | 30.9 | 0.111 |

| Play seated | 26.0 | 14.7 | ||

| Play running and jumping | 38.3 | 54.4 | ||

| “Do you like to engage in physical activity like running, dancing or any sport?” | Very little or nothing | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.890 |

| Sometimes | 30.1 | 26.5 | ||

| Very | 54.8 | 72.0 | ||

| “During a normal day, how much time do you spend sitting watching television, playing on the computer or tablet, using video games or chatting?” | Less than an hour/day | 27.4 | 39.7 | 0.104 |

| One or two hours/day | 50.7 | 50.0 | ||

| More than two hours/day | 21.9 | 10.3 | ||

| “In the last week, on how many days did you engage in a physical activity which left you out of breath and made you sweat for at least one hour a day?” | None or one day | 12.3 | 11.8 | 0.205 |

| Two to three days | 64.3 | 51.5 | ||

| Five or more days | 23.3 | 36.8 | ||

| “What would you do if you were served fruits or vegetables at one of the day's meals, such as breakfast, lunch or supper?” | I would eat it because I must | 34.2 | 29.4 | 0.827 |

| I would eat it because I like it | 61.6 | 66.2 | ||

| I wouldn’t eat it | 4.1 | 4.4 | ||

| “If you could choose what to eat to take care of your body and heart, what would you choose to eat at recess?” | Packaged foods, fried meat pies and sodas | 4.1 | 1.5 | 1.000 |

| A sandwich or fruit and water or milk | 95.9 | 97.0 | ||

| I prefer not to eat anything | 1.4 | 1.5 | ||

| “In the last week, how many days did you eat fruit or vegetables?” | One day or none | 8.2 | 1.5 | 0.180 |

| Two to four days | 30.1 | 33.8 | ||

| Five or more days | 61.6 | 64.7 | ||

| “In the last week, how many days did you eat milk products, eggs, fruit or cereals for breakfast?” | One day or none | 5.5 | 7.3 | 0.873 |

| Two to four days | 41.1 | 38.2 | ||

| Five or more days | 53.4 | 54.4 | ||

| “In the last week, on how many days did you eat foods such as French fries, fried meat pies, packaged foods or sodas?” | One day or none | 52.0 | 52.9 | 0.981 |

| Two to four days | 39.7 | 39.7 | ||

| Five or more days | 8.2 | 7.3 | ||

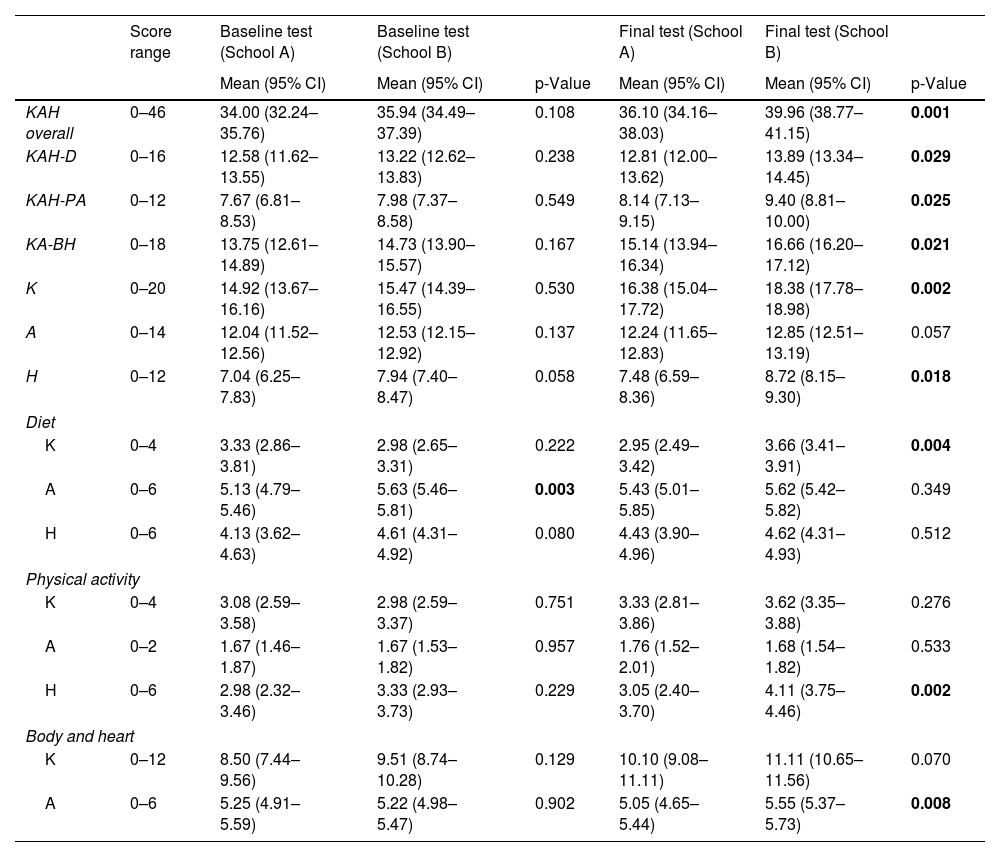

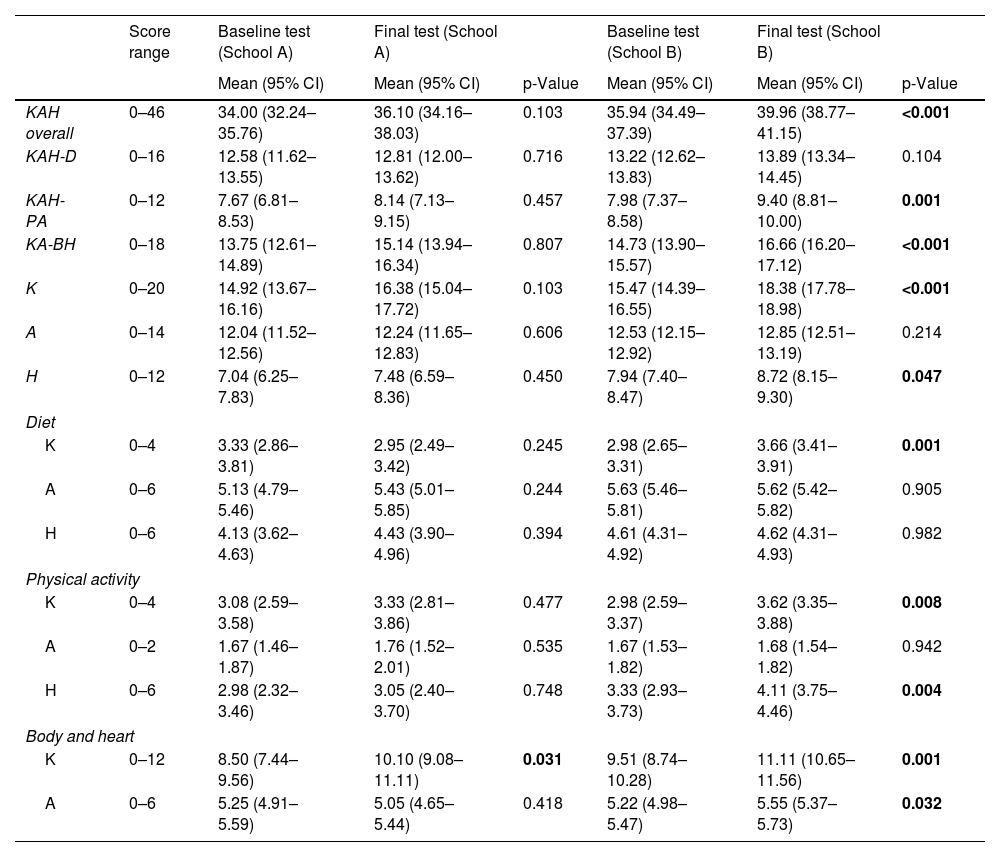

At baseline, the overall and individual KAH scores were similar between schools, with the exception for the attitude domain in D, where the low to medium income school (school B) scored better (Table 3). After the intervention, children from school B scored significantly higher in all topics compared to school A, but the difference was not significant for the D attitude and habits domains and PA knowledge and attitude domains. Moreover, comparing results in both schools, we can see that the improvement obtained in the overall study group was mainly driven by improvements in the low to medium income school (school B) (Table 4). In school A, only knowledge of BH improved. In school B, D was the only topic that did not improve, although knowledge of healthy diets was significantly better.

Comparative baseline and final questionnaire results between schools.

| Score range | Baseline test (School A) | Baseline test (School B) | Final test (School A) | Final test (School B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | p-Value | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| KAH overall | 0–46 | 34.00 (32.24–35.76) | 35.94 (34.49–37.39) | 0.108 | 36.10 (34.16–38.03) | 39.96 (38.77–41.15) | 0.001 |

| KAH-D | 0–16 | 12.58 (11.62–13.55) | 13.22 (12.62–13.83) | 0.238 | 12.81 (12.00–13.62) | 13.89 (13.34–14.45) | 0.029 |

| KAH-PA | 0–12 | 7.67 (6.81–8.53) | 7.98 (7.37–8.58) | 0.549 | 8.14 (7.13–9.15) | 9.40 (8.81–10.00) | 0.025 |

| KA-BH | 0–18 | 13.75 (12.61–14.89) | 14.73 (13.90–15.57) | 0.167 | 15.14 (13.94–16.34) | 16.66 (16.20–17.12) | 0.021 |

| K | 0–20 | 14.92 (13.67–16.16) | 15.47 (14.39–16.55) | 0.530 | 16.38 (15.04–17.72) | 18.38 (17.78–18.98) | 0.002 |

| A | 0–14 | 12.04 (11.52–12.56) | 12.53 (12.15–12.92) | 0.137 | 12.24 (11.65–12.83) | 12.85 (12.51–13.19) | 0.057 |

| H | 0–12 | 7.04 (6.25–7.83) | 7.94 (7.40–8.47) | 0.058 | 7.48 (6.59–8.36) | 8.72 (8.15–9.30) | 0.018 |

| Diet | |||||||

| K | 0–4 | 3.33 (2.86–3.81) | 2.98 (2.65–3.31) | 0.222 | 2.95 (2.49–3.42) | 3.66 (3.41–3.91) | 0.004 |

| A | 0–6 | 5.13 (4.79–5.46) | 5.63 (5.46–5.81) | 0.003 | 5.43 (5.01–5.85) | 5.62 (5.42–5.82) | 0.349 |

| H | 0–6 | 4.13 (3.62–4.63) | 4.61 (4.31–4.92) | 0.080 | 4.43 (3.90–4.96) | 4.62 (4.31–4.93) | 0.512 |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| K | 0–4 | 3.08 (2.59–3.58) | 2.98 (2.59–3.37) | 0.751 | 3.33 (2.81–3.86) | 3.62 (3.35–3.88) | 0.276 |

| A | 0–2 | 1.67 (1.46–1.87) | 1.67 (1.53–1.82) | 0.957 | 1.76 (1.52–2.01) | 1.68 (1.54–1.82) | 0.533 |

| H | 0–6 | 2.98 (2.32–3.46) | 3.33 (2.93–3.73) | 0.229 | 3.05 (2.40–3.70) | 4.11 (3.75–4.46) | 0.002 |

| Body and heart | |||||||

| K | 0–12 | 8.50 (7.44–9.56) | 9.51 (8.74–10.28) | 0.129 | 10.10 (9.08–11.11) | 11.11 (10.65–11.56) | 0.070 |

| A | 0–6 | 5.25 (4.91–5.59) | 5.22 (4.98–5.47) | 0.902 | 5.05 (4.65–5.44) | 5.55 (5.37–5.73) | 0.008 |

A: attitude; BH: body and heart; D: diet; H: habitus; K: knowledge; PA: physical activity.

Bold values represent p-values that are significant.

Results in each school.

| Score range | Baseline test (School A) | Final test (School A) | Baseline test (School B) | Final test (School B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | p-Value | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| KAH overall | 0–46 | 34.00 (32.24–35.76) | 36.10 (34.16–38.03) | 0.103 | 35.94 (34.49–37.39) | 39.96 (38.77–41.15) | <0.001 |

| KAH-D | 0–16 | 12.58 (11.62–13.55) | 12.81 (12.00–13.62) | 0.716 | 13.22 (12.62–13.83) | 13.89 (13.34–14.45) | 0.104 |

| KAH-PA | 0–12 | 7.67 (6.81–8.53) | 8.14 (7.13–9.15) | 0.457 | 7.98 (7.37–8.58) | 9.40 (8.81–10.00) | 0.001 |

| KA-BH | 0–18 | 13.75 (12.61–14.89) | 15.14 (13.94–16.34) | 0.807 | 14.73 (13.90–15.57) | 16.66 (16.20–17.12) | <0.001 |

| K | 0–20 | 14.92 (13.67–16.16) | 16.38 (15.04–17.72) | 0.103 | 15.47 (14.39–16.55) | 18.38 (17.78–18.98) | <0.001 |

| A | 0–14 | 12.04 (11.52–12.56) | 12.24 (11.65–12.83) | 0.606 | 12.53 (12.15–12.92) | 12.85 (12.51–13.19) | 0.214 |

| H | 0–12 | 7.04 (6.25–7.83) | 7.48 (6.59–8.36) | 0.450 | 7.94 (7.40–8.47) | 8.72 (8.15–9.30) | 0.047 |

| Diet | |||||||

| K | 0–4 | 3.33 (2.86–3.81) | 2.95 (2.49–3.42) | 0.245 | 2.98 (2.65–3.31) | 3.66 (3.41–3.91) | 0.001 |

| A | 0–6 | 5.13 (4.79–5.46) | 5.43 (5.01–5.85) | 0.244 | 5.63 (5.46–5.81) | 5.62 (5.42–5.82) | 0.905 |

| H | 0–6 | 4.13 (3.62–4.63) | 4.43 (3.90–4.96) | 0.394 | 4.61 (4.31–4.92) | 4.62 (4.31–4.93) | 0.982 |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| K | 0–4 | 3.08 (2.59–3.58) | 3.33 (2.81–3.86) | 0.477 | 2.98 (2.59–3.37) | 3.62 (3.35–3.88) | 0.008 |

| A | 0–2 | 1.67 (1.46–1.87) | 1.76 (1.52–2.01) | 0.535 | 1.67 (1.53–1.82) | 1.68 (1.54–1.82) | 0.942 |

| H | 0–6 | 2.98 (2.32–3.46) | 3.05 (2.40–3.70) | 0.748 | 3.33 (2.93–3.73) | 4.11 (3.75–4.46) | 0.004 |

| Body and heart | |||||||

| K | 0–12 | 8.50 (7.44–9.56) | 10.10 (9.08–11.11) | 0.031 | 9.51 (8.74–10.28) | 11.11 (10.65–11.56) | 0.001 |

| A | 0–6 | 5.25 (4.91–5.59) | 5.05 (4.65–5.44) | 0.418 | 5.22 (4.98–5.47) | 5.55 (5.37–5.73) | 0.032 |

A: attitude; BH: body and heart; D: diet; H: habitus; K: knowledge; PA: physical activity.

Bold values represent p-values that are significant.

Regarding habits and attitudes, school B showed better results for the question about not smoking later in life (90–98%, p=0.189), with more active playing after school (41–64%, p=0.074) and a decrease in the percentage that does intense physical activity less than one day a week (12–6%, p=0.081). In school A, the most relevant improvement was a decline in those that spend more than two hours a day in sedentary activities (37–19%, p=0.102).

DiscussionThe present pilot project demonstrated that this intervention improves lifestyle-related knowledge, attitudes, and habits in children aged 9 from urban low to medium income area in Lisbon. A single year of intervention led to an overall 9.8% differential increase, particularly regarding physical activity, and we can hypothesize that this effect will continue to increase overtime if the program continues and even be maintained thereafter.

The Si! Program, one of the largest projects for health education in children, conducted in Spain (a reference for comparison), and designed to cover the entire education system in Spain from preschool to secondary education (from 3 to 16 years old), showed that in preschoolers, aged 3–5 years, their program improved the overall KAH scores and most of its individual components, translating into beneficial effect on adiposity.10–13 The maximum effect was observed when started at the earliest age and maintained over 3 years.11,13 However, these improvements in preschool children were not sustained. In children previously intervened at 3–5 years of age, no overall significant differences between the intervention and control groups were observed at 9–13 years.17 Moreover, no booster effect was detected when reintervened again at a later age.17 Nevertheless, children with high adherence rates to these reinterventions had significant benefits, confirming the need for reintervention strategies at multiple stages to induce sustained health promotion effects.17 In addition, this program also showed that starting this educational intervention in older children (adolescents from the 7th grade, aged 12 years), has an overall neutral effect on cardiovascular health, including measures of obesity, confirming the need to start this health education early in life.19

When comparing the results obtained in Spain in preschoolers with our own results in older children, the largest effect was observed for the PA component in the Si! Program, like in our project. The BH component was not effective in Spain, but in our experience, we obtained significant improvements, mainly in the knowledge domain, which can possibly be explained by the fact that older children (aged 9 year) may have a better perception and understanding of those concepts. In addition, for the D component, in Spain it was only effective in very young children and not in other age groups, as we observed in our study. Our explanation for our findings regarding the D component is that our program coexisted with other health promotion strategies at a local level. In fact, at the beginning of the school year (a few weeks before our project) the children had a week-intervention promoted by the Local Primary Care Center, dedicated to healthy diets. This may explain the elevated D scores at baseline and that did not improve further during the year. Nevertheless, our nutrition specific session was delivered at the end of term and can be considered a reintervention in this setting.

In general, the magnitude of the effect obtained in the KAH questionnaire is not very high, albeit significant. However, it is comparable to that observed in the Spanish studies, both in preschoolers and in the high adherence reintervention in children aged 9–12 years, suggesting an overall positive effect of the program.12,13,17

Children's habits can be influenced by their parents’ health awareness and other socioeconomic characteristics. Previous data from Spain showed that children from parents with a low educational level had lower odds for scoring positively on items such as using olive oil and not skipping breakfast, and higher odds for meeting the recommendations for consuming pulses (beans, peas, lentils, or chickpeas).14 On the contrary, parental high-income status is associated with regular consumption of fish, fresh or cooked vegetables, nuts, and olive oil, but they skip breakfast and have sweets and candy more often.14 Another negative point is that they also go more often to a fast-food restaurant and have more commercially baked goods or pastries for breakfast.14 It was noteworthy that the largest differences seen in children from low-socioeconomic status households (lower olive oil consumption, higher consumption of pulses, and higher frequency of pasta/rice consumption), is clearly related to purchasing power. Children with parents originating from Europe also had better scoring.14 No significant association was found in Spain for income status and physical activity.14 In our data, parental socioeconomic variables also seem to determine the effect of the intervention in children. The differential change in the overall KAH score and in all major components was greater in children from families with lower income. Also, in children from the lower income school, there was a more significant improvement regarding physical activity, particularly in after school activities (less time watching television and playing videogames) and more intense physical activities, which could include walking to school. These results emphasize the importance of addressing socioeconomic variables, as different cultural or economic backgrounds may lead to different effect sizes.

LimitationsThe educational year 2022/2023 was marked by national teacher protests and strikes, which had an inevitable impact on the school program delivery. If it were not for that, the program could have had more impact on the results obtained. Teacher motivation is crucial for optimal implementation – highly motivated teachers are more engaged, and their motivation is linked to that of their students. It has also been previously shown that adherence is important, and children aged 9–12 years that completed <50% of the Si! Program modules (low adherence) had a significantly smaller change from baseline in overall KAH score compared to high adherence group (>75% of the program).20

The questionnaires were anonymous and therefore, it was not possible to correlate the results with individual characteristics, such as cultural and religious background and parental socioeconomic characteristics. Cultural practices can be related to food choices and children's transportation methods to school can also have implications on daily physical activity. An assessment of the socioeconomic setting was only possible in an indirect way, which might not have been very accurate. Also, questionnaires can carry a subjective component that may affect the results. We acknowledge the limitations of self-reported measurements of diet and physical activity; however, it has been previously considered to be simpler and better suited to children, avoiding parental reporting bias if an alternative comprehensive questionnaire had been applied.16,17

We do not have long-term data and therefore, we do not know if a sustained effect can be observed. From previous results, we expect this not to be the case. Ideally, educational projects in school children should be extended to include other players, for better immediate and long-term results. For school-based health promotion programs to be successful, not only children must be targeted but also their families, teachers, and the whole school and community environment. Parents are key to providing support and encouragement to children, including access to healthy food and opportunities for physical activity. Also, the support of local government education entities is vital successfully introducing a health promotion program into the school curriculum.

ConclusionsAn educational project for cardiovascular health can be implemented successfully in children aged 9 years from an urban low to middle income area. In general, knowledge domains were the most effectively changed, but physical activity also showed significant improvement. A neutral effect was observed for the diet component. However, this finding needs to be further confirmed in larger populations and ascertained whether the beneficial impact is sustained over time.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.

The authors express their gratitude to Teresa André, Head of the Elementary School Mestre Querubim Lapa, and Maria Jorge Figueiredo, Head of the Elementary School Marquesa de Alorna, for accepting the challenge to participate in this pilot project.