In patients with supraventricular arrhythmias and high ventricular rate, unresponsive to rate and rhythm control therapy or catheter ablation, atrioventricular (AV) node ablation may be performed.

ObjectivesTo assess long-term outcomes after AV node ablation and to analyze predictors of adverse events.

MethodsWe performed a detailed retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent AV node ablation between February 1997 and February 2019, in a single Portuguese tertiary center.

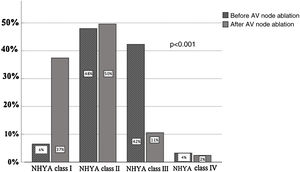

ResultsA total of 123 patients, mean age 69±9 years and 52% male, underwent AV node ablation. Most of them presented atrial fibrillation at baseline (65%). During a median follow-up of 8.5 years (interquartile range 3.8-11.8), patients improved heart failure (HF)

functional class (NYHA class III-IV 46% versus 13%, p=0.001), and there were reductions in hospitalizations due to HF (0.98±1.3 versus 0.28±0.8, p=0.001) and emergency department (ED) visits (1.1±1 versus 0.17±0.7, p=0.0001). There were no device-related complications. Despite permanent pacemaker stimulation, left ventricular ejection fraction did not worsen (47±13% vs. 47%±12, p=0.63). Twenty-eight patients died (23%). The number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation was an independent predictor of the composite adverse outcome (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.24-2.61, p=0.002).

ConclusionsDespite pacemaker dependency, the clinical benefit of AV node ablation persisted at long-term follow-up. The number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation was an independent predictor of the composite adverse outcome. AV node ablation should probably be considered earlier in the treatment of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias and HF, especially in cases that are unsuitable for selective ablation of the specific arrhythmia.

Nos doentes com disritmias supraventriculares e frequência ventricular elevada, irresponsivos à terapêutica para controlo da frequência e do ritmo, ou à ablação por catéter, a ablação do nódulo auriculoventricular (ANAV) pode ser realizada.

ObjetivosAvaliar os resultados em longo prazo após a ANAV e analisar preditores de eventos adversos.

MétodosAnálise retrospetiva detalhada, dos doentes submetidos à ANAV entre fevereiro 1997 e fevereiro 2019, num centro terciário português.

ResultadosForam submetidos 123 doentes à ANAV: idade média 69 ± 9 anos e 52% homens. A maioria apresentou fibrilhação auricular (65%). Num período mediano de seguimento de 8,5 anos (intervalo interquartil 3,8-11,8), houve melhoria da classe funcional de insuficiência cardíaca (IC) (classe NYHA III-IV 46% versus 13%, p = 0,001) e redução dos internamentos por IC (0,98±1,3 versus 0,28±0,8, p=0,001), redução dos recursos ao serviço de urgência (SU) (1,1±1 versus 0,17±0,7, p=0,0001). Não houve complicações relacionadas ao dispositivo. Apesar da estimulação permanente de pacemaker, a FEVE não agravou (47%±13 versus 47%±12, p=0,63). Faleceram 28 doentes (23%). O número de recursos ao SU por IC antes do procedimento foi preditor independente do composto de eventos adversos (OR 1,8, IC95%, 24-2,61, p=0,002).

ConclusõesApesar da dependência de pacemaker, o benefício clínico da ANAV persistiu a longo prazo. O número de recursos ao SU por IC antes do procedimento foi preditor do composto de eventos adversos. Provavelmente, a ANAV deveria ser considerada mais cedo no tratamento de doentes com disritmias supraventriculares e IC, sobretudo nos casos em que a ablação seletiva da disritmia seja inapropriada.

Supraventricular arrhythmias present a challenge for the management of patients who develop a high ventricular rate and symptoms refractory to medical therapy.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most frequent sustained arrhythmia in clinical practice.1,2 AF promotes heart failure (HF) decompensation leading to hospitalizations, and 10-40% of AF patients are hospitalized every year.3 Clinical trials have demonstrated that in about one quarter of these patients, an adequate rate control strategy cannot be achieved.4,5 Currently, in patients with supraventricular arrhythmias who are unresponsive or intolerant to pharmacological therapy, rhythm control may be achieved with electrical cardioversion and catheter ablation. Pulmonary veins isolation is a well-established AF treatment, although delayed referral of patients, particularly those with longstanding persistent AF, may reduce its efficacy.6 If these therapies are unsuccessful, atrioventricular (AV) node ablation may be performed.1,2

AV node ablation was first performed in humans in 1981, using high-energy direct current (300-500 J) delivered from a portable defibrillator.7 Since its introduction in clinical practice the technique has evolved and nowadays it is mostly performed using radiofrequency ablation followed by permanent pacemaker implantation, a strategy named “ablate and pace”.8 This strategy has proven efficacy,9–12 although patients become pacemaker-dependent and complications may occur, such as ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death.13

Most studies have reported symptomatic improvement and favorable safety results after AV node ablation in follow-up periods of around five years.14,15 However, long-term right ventricular (RV) stimulation may lead to left ventricular (LV) dysfunction.16–18 Considering this deleterious consequence, few studies have assessed in detail the clinical, procedural and echocardiographic outcomes after AV node ablation beyond five years.19,20 Therefore, in this study we aimed to assess long-term outcomes after AV node ablation and to analyze clinical predictors of adverse events.

MethodsStudy populationWe retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients who underwent AV node ablation between February 1997 and February 2019 in a single tertiary center, Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho Hospital Center, Porto. The local ethics committee approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were considered to have refractory supraventricular arrhythmia if they had uncontrolled symptoms after appropriate pharmacological therapies had been tried for periods appropriate to the pharmacokinetics of the agents used, and after exclusion of reversible causes.21

Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic assessmentBaseline rhythm was recorded by 12-lead electrocardiogram and 24-hour Holter monitoring. Electrocardiographic analyses were performed according to the recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram.22

Transthoracic echocardiograms were performed before and after the procedure. Stored images and reports were analyzed. Quantification of cardiac chambers was performed as recommended by the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging.23

Atrioventricular node ablation procedure characteristicsRadiofrequency AV node ablation was performed under fluoroscopic guidance. Following right femoral vein access, the ablation catheter was advanced across the tricuspid valve annulus and was then withdrawn with septal torque until the largest His signal was visualized. Ablation was performed in the atrioventricular node or at the most proximal penetrating part of the His bundle. In the event of failure of right-side ablation attempts, AV node ablation was performed from the left ventricle via a retrograde aortic approach. Dual-chamber pacemakers were implanted in patients with paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias while those with permanent arrhythmias, particularly AF, received a single-chamber pacemaker.

Immediate success was defined as permanent AV block after catheter ablation. All patients were monitored in the ward for at least 24 hours and a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed before discharge. After AV node ablation, devices were uniformly programmed in VVI mode at 90 beats per minute (bpm) for one month. Devices were systematically interrogated at 24 hours, the first month, the sixth month and biannually thereafter to assess the presence of symptoms, arrhythmias and device parameters.

OutcomesPrimary outcomes were defined as death, unplanned hospitalizations, unplanned emergency department (ED) visits due to heart failure (HF) and NYHA functional class worsening after AV node ablation. The composite outcome was defined as the composite of the primary outcomes.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were reported as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. Normality of distribution of continuous variables was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences were analyzed using the Friedman and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. All statistical tests were two-sided and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed to identify predictors of adverse outcomes after AV node ablation. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

ResultsPatient characteristicsA total of 123 patients, mean age 69±9 years and 52% male, underwent AV node ablation. The clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n=123).

| Age, years | 69±9 |

| Male gender | 65 (52%) |

| Body mass index | 27±4 |

| Comorbidities | |

| NYHA class I-II | 67 (54%) |

| NYHA class III-IV | 56 (46%) |

| Hypertension | 52 (42%) |

| Diabetes | 28 (23%) |

| Obesity | 14 (11%) |

| DCM | 31 (25%) |

| Valvular heart disease | 27 (22%) |

| COPD | 4 (3%) |

| GFR <60 ml/min | 24 (20%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (7%) |

| CAD | 19 (15%) |

| Hospitalizations due to HF, mean (previous 12 months) | 0.98±1 |

| ED visits due to HF, mean (previous 12 months) | 1.1±1 |

| Symptoms | |

| Palpitations/chest pain | 49 (40%)/3 (2%) |

| Dyspnea/decompensated HF | 8 (7%)/53 (43%) |

| Syncope/dizziness | 6 (5%)/2 (2%) |

| Asymptomatic | 2 (2%) |

| Previous electrical treatment | |

| Electrical cardioversion | 28 (23%) |

| AF catheter ablation | 10 (8%) |

| Cavotricuspid isthmus ablation | 14 (11%) |

| Medication | |

| Beta-blockers/amiodarone | 71 (58%)/44 (36%) |

| Other antiarrhythmic agents | 22 (18%) |

| Digoxin | 34 (28%) |

| Anticoagulants/antiplatelet agents | 83 (68%)/15 (12%) |

| ACEIs/ARBs | 65 (53%) |

| Spironolactone/other diuretics | 17 (14%)/55 (45%) |

| Echocardiographic characteristics | |

| LA diameter, mm | 51±7 |

| LVEDD, mm | 56±9 |

| Mean LVEF, % | 47±13 |

| LVEF <35% | 21 (17%) |

| Electrocardiographic characteristics | |

| Baseline rhythm | |

| Sinus | 17 (14%) |

| AF | 80 (65%) |

| Atrial flutter | 21 (17%) |

| Atrial tachycardia | 3 (2%) |

| Pacemaker | 2 (2%) |

| Arrhythmia duration | |

| Permanent | 65 (53%) |

| Persistent/paroxysmal | 21 (17%)/37 (30%) |

| Heart rate on ECG, bpm | 114±33 |

| Heart rate on 24-h Holter, bpm | 90±27 |

| QRS duration, ms | 117±32 |

| LBBB/RBBB | 13 (11%)/2 (2%) |

| Pacemaker/CRT/ICD | 2 (2%)/10 (8%)/1 (1%) |

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AF: atrial fibrillation; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; CAD: coronary artery disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy device; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; ECG: electrocardiogram; ED: emergency department; GFR: glomerular filtration rate (Cockcroft-Gault formula); HF: heart failure; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LA: left atrial; LBBB: left bundle branch block; LVEDD: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association functional class; RBBB: right bundle branch block.

AF was the baseline rhythm in most patients (65%) at the time of the procedure. The mean ventricular rate was 114±33 bpm, mean LVEF was 47%±13 and 46% of patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III-IV. In the 12 months prior to the procedure, 32% and 44% of patients had at least one unplanned hospitalization and one ED visit due to decompensated HF, respectively.

Procedural characteristicsDetailed information on the procedure and outcomes is shown in Table 2.

Procedure and outcomes.

| Indication | |

|---|---|

| AF/atrial flutter (drug-refractory/uncontrolled HF) | 57 (46%)/15 (12%) |

| Inappropriate ICD shocks | 2 (2%) |

| SND (severely symptomatic or uncontrolled tachycardia) | 12 (10%) |

| Tachycardiomyopathy | 27 (22%) |

| Low biventricular pacing percentage | 10 (8%) |

| Devices implanted before procedure (n=110) | |

| Pacemaker | 90 (82%) |

| CRT-P | 7 (6%) |

| CRT-D | 9 (8%) |

| ICD | 4 (4%) |

| AV node ablation procedure, elective | 123 (100%) |

| Anterograde approach | 123 (100%) |

| Retrograde approach | 13 (11%) |

| Total procedure time, min | 46±18 |

| Fluoroscopy/ablation times, min | 8±7/2±2 |

| Immediate success/major complications | 123 (100%)/0 |

| Median follow-up, years (IQR) | 8.5 (3.8-11.8) |

| NYHA class I-II | 107 (87%) |

| NYHA class III-IV | 16 (13%) |

| Hospitalizations due to HF (previous 12 months) | 0.28±0.8 |

| ED visits due to HF (previous 12 months) | 0.17±0.7 |

| QRS under ventricular pacing, ms | 173±18 |

| LVEDD, mm | 57±9 |

| Mean LVEF, % | 47±12 |

| AV node reconduction and repeat procedure | 4 (3%) |

| Major adverse events | 12 (10%) |

| Death | 28 (23%) |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AV: atrioventricular; CRT-D: cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; CRT-P: cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker; ED: emergency department; HF: heart failure; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEDD: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association functional class.

Most patients presented severe symptoms or uncontrolled HF due to AF (46%) or atrial flutter (12%). Ten patients (8%) with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices presented low biventricular pacing percentage and two patients (2%) with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) received inappropriate shocks related to supraventricular tachycardia.

AV node ablation was successfully performed in all 123 patients, without immediate major adverse events. One patient presented femoral hematoma at discharge and needed prolonged hospitalization for surveillance. Permanent device insertion was performed in the same procedure in 110 patients: 90 with pacemakers (82%), seven with CRT pacemakers (6%), nine with CRT defibrillators (8%) and four with ICDs (4%).

Clinical outcomes and echocardiographyDuring a median follow-up of 8.5 years (IQR 3.8-11.8), there were no device-related complications.

NYHA functional class improved, as shown in Figure 1 (NYHA class III-IV 46% versus 13%, p = 0.001), and hospitalizations (0.98±1.3 versus 0.28±0.8, p = 0.001) and ED visits due to HF (1.1±1 versus 0.17±0.7, p = 0.0001) decreased. There were no differences in mean LVEF (47±13% vs. 47±12%, p=0.63) or left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) (56±9 vs. 57±9 mm, p=0.85). Four (3%) patients needed a redo procedure. During follow-up 28 patients died (23%).

Clinical predictors of adverse outcomesData regarding predictors of adverse outcomes are shown in Table 3. Univariate analysis of predictors of death from any cause after AV node ablation was statistically significant for age (odds ratio [OR] 1.05 per year, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00-1.11, p=0.029), number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.06-1.98, p=0.019) and number of hospitalizations (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.00-2.30, p=0.045).

Predictors of outcomes after atrioventricular node ablation on univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis of outcomes (death, hospitalizations, ED visits and HF worsening) | |||

| No. of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation | 1.63 | 1.21-2.20 | 0.001 |

| No. of hospitalizations due to HF before AV node ablation | 1.63 | 1.11-2.38 | 0.012 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 3.95 | 1.37-11.3 | 0.011 |

| ACEIs/ARBs | 2.2 | 0.97-5 | 0.058 |

| Spironolactone | 3.31 | 1.14-9.59 | 0.027 |

| Other diuretics | 2.75 | 1.23-6.14 | 0.013 |

| Multivariate analysis of outcomes (death, hospitalizations, ED visits and HF worsening) | |||

| No. of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation | 1.8 | 1.24-2.61 | 0.002 |

| Death from any cause after AV node ablation | |||

| Age | 1.05 | 1.00-1.11 | 0.029 |

| BMI | 0.33 | 0.12-0.90 | 0.030 |

| No. of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation | 1.45 | 1.06-1.98 | 0.019 |

| No. of hospitalizations due to HF before AV node ablation | 1.52 | 1.00-2.30 | 0.045 |

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; AV: atrioventricular; BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; ED: emergency department; HF: heart failure; OR: odds ratio.

In multivariate analysis of outcomes, only the number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.24-2.61, p=0.002) was a significant predictor of the composite outcome (C-statistic of the final model 0.012, p=0.042; Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p=0.31).

DiscussionIn this study of consecutive patients undergoing AV node ablation, we observed that: (1) despite pacemaker dependency, the clinical benefit of ablation persisted at long-term follow-up, with reductions in hospitalizations and ED visits due to HF and improvement in NYHA functional class; (2) there were no significant differences in mean LVEF and LVEDD before and after the procedure; (3) the number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation was an independent predictor of the composite adverse outcome.

With regard to long-term outcomes, several important studies have assessed the outcomes of AV node ablation and reported clinical improvement and a favorable safety profile. Although these studies had shorter follow-up periods than ours (range 1-4 years), mortality varied between 12% and 41%.24–29 After a median follow-up of 8.5 years, mortality in our study (23%) was within this range. Similar mortality (22%) was reported in a retrospective study of 162 patients with AF who underwent AV node ablation.30

Our results are also in agreement with previous studies that reported improvements in symptoms, reduction of NYHA functional class and hospitalizations after AV node ablation.31,32 The reductions in hospitalizations and ED visits due to HF are probably related to improvements in patients’ general clinical condition in the context of controlled heart rate, reduced R-R interval variability and improved diastolic filling.33 In line with these results and although patients became pacemaker-dependent, in our study the clinical benefits after the procedure persisted in long-term follow up.

No significant differences were observed regarding LVEF and LVEDD before and after AV node ablation in the present study. These results are similar to previous reports.29 LV dyssynchrony and dysfunction induced by the abnormal electrical activation pattern of pacing have been documented in other clinical contexts.16 Particularly after AV node ablation, conflicting results have been observed regarding the impact of ventricular pacing on LV function. In two prospective studies34,35 that included AF patients with and without structural heart disease (29 and 30 patients, follow-up 0.6 and 6.4 years) and in the Ablate and Pace Trial36 (156 patients, follow-up one year), it was observed that LVEF increased after AV node ablation in patients with LVEF <50% at baseline, while those with normal LVEF at baseline had no change during follow-up. Different results were found in observational studies, in which normal LVEF at baseline, assessed by echocardiography and radionuclide ventriculography (12-55 patients, follow-up 0.25-3.8 years), decreased after AV node ablation.37–39 Vernooy et al.,40 in a study with a similar follow-up period to ours (seven years) but with a smaller population (45 patients), also found that after AV node ablation, RV pacing decreased LVEF in patients with LVEDD <50 mm at baseline. These differences between studies may be related to patient selection criteria, timing and method of LV measurement, sample size and follow-up periods.

Various pacing strategies for patients with AF undergoing AV node ablation have been proposed to overcome the detrimental effects of ventricular pacing on cardiac function.41,42 Recent evidence suggests that biventricular pacing could be superior to RV pacing in reducing hospitalizations in these patients.32 Biventricular pacemakers provide coordinated activation of the interventricular septum and the lateral wall, resulting in synchronous LV contraction. This technique has proved valuable in improving prognosis in patients with HF and wide QRS complex.43 Previous trials in patients with AF undergoing AV node ablation that compared biventricular pacing with RV pacing44,45 and with pharmacological rate-control therapy46,47 found that biventricular pacing improved LVEF and reduced hospitalizations and death due to HF. Of note, one trial was conducted exclusively in patients with narrow QRS and favorable results were observed with significantly reduced mortality from any cause after AV node ablation.46 In our study, about one fifth of the patients had a cardiac resynchronization therapy device implanted after AV node ablation in accordance with the current recommendations,43,48 and there was an overall clinical benefit, irrespective of the implanted device. Beyond conventional biventricular pacing, His bundle pacing is presently a safe alternative to right ventricular pacing after AV node ablation, with improvements in NYHA class and LVEF.15,49–52 Based on this evidence,32,44,51,53 the guidelines54 recommend AV node ablation followed by biventricular or His-bundle pacing in patients with tachycardiomyopathy.

Predictors of clinical outcomesThe number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation was a consistent predictor in univariate and multivariate analysis of the adverse outcomes in this study. HF patients who need frequent unplanned medical visits present progressive worsening of functional capacity, quality of life and prognosis.55 Consequently, it may be hypothesized that patients with advanced HF, who need multiple acute care services before AV node ablation, present higher rates of adverse outcomes and less clinical benefits after the procedure.

LimitationsThe main limitation of this study is its retrospective and nonrandomized nature. The procedure was performed at a single institution and the reproducibility of our results at other laboratories remains to be assessed. Additionally, information regarding causes of death was unavailable in some patients.

ConclusionsAV node ablation is a useful and safe procedure for the treatment of supraventricular arrhythmias, particularly in the context of tachycardiomyopathy.

In our study, despite pacemaker dependency, the clinical benefit of AV node ablation persisted in long-term follow-up, with reductions in hospitalizations and ED visits due to HF and improvement in NYHA functional class. The number of ED visits due to HF before AV node ablation was an independent predictor of adverse outcomes. This intervention should be probably considered earlier in the treatment of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias and HF, especially in cases that are unsuitable for selective ablation of the specific arrhythmia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.