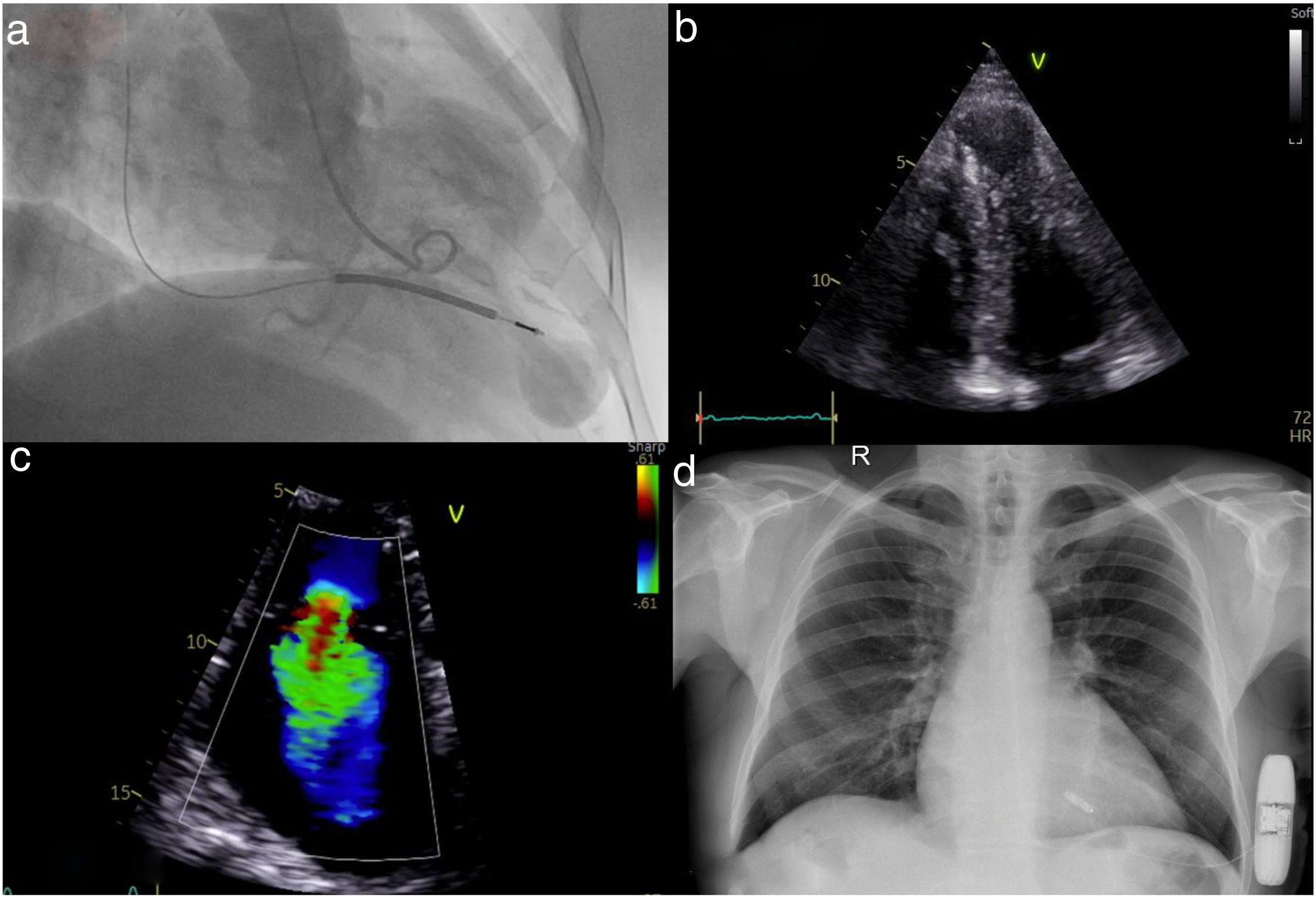

A 60-year-old patient with a medical history of aneurysmal sarcomeric apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (MYBPC3 mutation) and permanent atrial fibrillation was referred to our clinic for assessment due to two episodes of syncope (Video 1). As a first step, 24-h ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring was utilized and revealed atrial fibrillation with pauses of up to 3.5 s during waking hours and short bursts of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia.1 Due to an HCM Risk-SCD score of 7.6%,2 we decided to proceed with the placement of a transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in order to address both probable syncopal etiologies.

Following implantation, the patient presented for his yearly reassessment with lower limb edema and mild dyspnea on exertion. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed new-onset severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) due to anterior leaflet malcoaptation from the right ventricular ICD lead (Figure 1a–c).

(a) Left ventriculography in systole revealing an apical aneurysm; (b) apical 4-chamber echocardiographic view with hypertrophic left ventricular apical segments and a prominent apical aneurysm; (c) severe tricuspid regurgitation; (d) chest X-ray after implantation of a leadless pacemaker and subcutaneous defibrillator.

TR following intravenous device placement is a well-known complication, mainly occurring due to leaflet perforation, avulsion, or damage to the subvalvular apparatus. Further interaction of the device leads can result in impingement of the leaflets, malcoaptation, and significant regurgitation. Leaflet adhesion, fibrosis, and encapsulation further contribute to valve incompetence.3 TR historically is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality and unfortunately leads to a vicious circle of more TR and right ventricular failure. Secondary TR is known to improve following diuretic therapy, but medical therapy has little effect when primary disease of the valve is present. No relevant prospective data exist in the literature in cases of TR due to pacemaker leads.

After thorough discussion, we proceeded with extraction of the ICD and implantation of both a leadless pacemaker (LP) and a subcutaneous ICD (s-ICD), as the latter lacks pacing capability (Figure 1d). Although leadless and subcutaneous device-based therapies are usually indicated in patients with limited upper extremity venous access, we were faced with a symptomatic iatrogenic valvular insufficiency that led us to device extraction. An attempt at lead removal after a certain period of time is fraught with its own complications and we are not sure if this leads to improvement in the severity of TR or right ventricular function. Simultaneous LP and s-ICD implantation is a viable alternative, although evidence in the literature is scarce. A key concern with combined s-ICD and LP therapy is that pacing spikes and QRS components might be oversensed by the s-ICD and could interfere with ventricular arrhythmia detection algorithms.4 To tackle this, we simultaneously perform LP and s-ICD interrogation in both supine and standing positions pre-discharge.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.