Coronary spasm can cause myocardial ischemia and angina in both patients with and without obstructive coronary artery disease. However, provocation tests using intracoronary acetylcholine (ACh) have been rarely performed in the Western world.

Case reportWe report a case of a 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and a mechanical aortic prosthesis who presented in the emergency room with acute-onset chest pain, widespread ST-segment depression and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, with no signs of prosthesis dysfunction. Emergent coronary angiography excluded obstructive coronary artery disease. Pain relief and normalization of ST segment and systolic function occurred within six hours. The patient was treated for a possible thromboembolic myocardial infarction and was discharged home asymptomatic. Two weeks later, cardiac magnetic resonance was performed showing inferoseptal transmural infarct scar, inferior and inferolateral subendocardial infarct and mid-basal ischemia in the anterior and anterolateral walls. She was readmitted with recurrence of chest pain and it was decided to perform a provocation test with ACh. After injection of ACh into the left anterior descending artery, chest pain, ST-segment depression, blood flow impairment (TIMI 1) and transient grade 3 atrioventricular (AV) block occurred. Intracoronary administration of nitrates reversed the coronary spasm and AV conduction disturbances. Twenty minutes later, chest pain and ischemic ST changes recurred; there was no response to vasodilators and the patient developed cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity. Advanced life support was maintained for 32 minutes without return of spontaneous circulation.

ConclusionsProvocation tests have a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of vasospastic angina. Although it is rare, these tests have the potential risk of irreversible spasm leading to arrhythmia and death.

O espasmo coronário pode causar isquemia miocárdica e angina em doentes com e sem doença coronária obstrutiva. Contudo, os testes de provocação com administração intracoronária de acetilcolina (ACh) têm sido raramente usados no mundo ocidental.

Descrição do casoMulher de 75 anos com hipertensão arterial e prótese mecânica aórtica admitida no serviço de urgência por dor torácica aguda, depressão generalizada do segmento ST e disfunção sistólica grave do ventrículo esquerdo sem evidência de disfunção protésica. Realizámos angiografia coronária emergente que excluiu doença coronária obstrutiva. Seis horas após admissão, a dor, as alterações de ST e a disfunção ventricular normalizaram. Foi tratado como possível enfarte do miocárdio tromboembólico e teve alta assintomática. Duas semanas após, realizámos ressonância magnética cardíaca que mostrou cicatriz de enfarte transmural inferoseptal e de enfarte subendocárdico inferior e inferolateral, e isquemia anterior e ântero-lateral. A doente foi readmitida pela mesma sintomatologia e decidimos realizar estudo de provocação com ACh. Após a injeção de ACh na artéria descendente anterior documentámos dor torácica, depressão do segmento-ST, compromisso do fluxo (TIMI 1) e bloqueio atrioventricular (AV) completo. A administração intracoronária de nitratos reverteu o espasmo coronário e a perturbação da condução AV. No entanto, 20 minutos depois, houve recorrência de dor e alterações de ST sem resposta aos vasodilatadores evoluindo a doente para atividade elétrica sem pulso. Mantivemos suporte avançado de vida durante 32 minutos sem recuperação da circulação espontânea.

ConclusãoOs testes de provocação têm elevada sensibilidade e especificidade para o diagnóstico de angina vasospática. Apesar de raro, estes testes também podem levar ao espasmo coronário irreversível, arritmia e morte.

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and aortic valve replacement with a mechanical prosthesis ten years earlier presented to the emergency room (ER) with acute-onset chest pain and diaphoresis. She described a three-month history of chest pain episodes of short duration with no clear relation with effort with no peripheral edemas or orthopnea.

On initial evaluation, the patient reported intense chest pressure but was not in acute distress. She was afebrile, with blood pressure 72/44 mmHg, heart rate 110 beats/min, and respiratory rate 32 breaths/min; pulse oximetry revealed oxygen saturation of 94% in room air. Chest auscultation revealed regular prosthetic sounds with a systolic murmur; rales were heard in both lung fields. The abdominal examination was unremarkable. Her lower extremities were pale and cold but showed no edema. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

The patient's hypotension and tachycardia suggested the early stages of shock and thus warranted urgent diagnostic testing and management, particularly in a patient with chest pressure. Her hypertension increased the likelihood of an acute coronary syndrome or aortic dissection. The systolic murmur may have been related to prosthetic valve dysfunction or to a mechanical complication of myocardial infarction, such as ventricular septal rupture or papillary muscle rupture, causing acute mitral regurgitation.

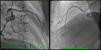

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), obtained approximately six hours after the onset of chest pressure, revealed normal sinus rhythm with widespread ST-segment depression (1–2 mm in leads V2 to V6, DI and aVl, DII–III and aVF) (Figure 1A).

(A–C) Electrocardiography. A 12-lead electrocardiogram obtained six hours after onset of chest pressure revealed normal sinus rhythm with widespread ST-segment depression (1–2 mm in leads V2 to V6, DI and aVl, DII–III and aVF) (A); the chest pain and ST-segment depression resolved (B); the patient was readmitted with recurrence of chest pain and marked ST depression in all precordial leads (C).

The electrocardiographic findings were consistent with myocardial ischemia, but other conditions associated with ST-segment depression and mimicking myocardial ischemia also had to be considered. An echocardiogram can help with differential diagnosis by identifying regional wall motion abnormalities, a native or prosthetic valve disorder, pericardial effusion, mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction (as noted above), or even proximal aortic disease.

Transthoracic echocardiography performed in the ER revealed global hypokinesis and impaired left ventricular function with severely depressed ejection fraction (EF); there were no signs of prosthesis dysfunction and the peak gradient between aortic and left ventricular systolic pressures was 26 mmHg.

The patient became progressively less responsive, her blood pressure decreased and metabolic acidosis (pH 7.33, PaCO2 23.3 mmHg, HCO3 12.1 mmol/l and base excess −13.8) ensued. In the presence of signs of shock, most probably for cardiocirculatory causes, dobutamine and noradrenaline were initiated.

The patient was also given aspirin 250 mg orally, and clopidogrel 600 mg orally. Her INR was 3.6.

Laboratory results were as follows: hemoglobin 11.1 g/dl, platelet count 190000/ml, white-cell count 10300/ml, serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dl, blood glucose 106 mg/dl, creatine kinase 135 IU/dl, creatine kinase MB isoenzyme 14.1 ng/ml, and serum troponin I 1.43 ng/ml.

Mildly elevated cardiac biomarkers confirmed myocardial injury but were inconsistent with chest pain six hours after clinical onset. These levels were somewhat unexpected and suggested either spontaneous intermittent coronary reperfusion throughout the day or another cardiovascular condition, such as apical ballooning syndrome, myocarditis or pulmonary embolism.

Preparations were made for transfer to a hospital where percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) could be carried out. On the patient's arrival at the PCI-capable hospital, her chest pressure had improved but was not completely resolved; her blood pressure was 118/61 mmHg and heart rate 97 beats/min.

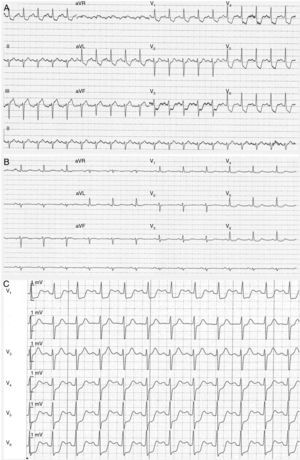

Coronary angiography revealed a 40% luminal stenosis in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) with no evidence of plaque rupture or thrombus (Figure 2A). Left ventriculography showed global hypokinesia with only mildly reduced left ventricular EF.

The patient was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit. Aspirin therapy was continued and treatment with a statin was started. The chest pain and electrocardiographic ST depression resolved overnight (Figure 1B), and cardiac biomarker levels decreased from the peak values noted at admission. She was conscious and afebrile; her blood pressure rose, heart rate and urine output were normal, and she was weaned from inotropic support.

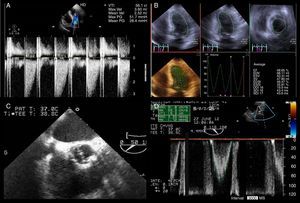

The patient remained stable and the repeated transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal dimensions of the cardiac chambers and normally functioning aortic prosthesis, with a maximum gradient between aortic and left ventricular systolic pressures of 20 mmHg. No wall motion abnormalities were seen and EF was 48% (Figure 3A and B). To better assess the aortic prosthesis, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed, which provided no additional information (Figure 3C and D).

(A–D) Echocardiography. Transthoracic echocardiogram performed after pain relief showed mean gradient between the aortic and left ventricular systolic pressures of 26 mmHg (A) and slightly impaired left ventricular systolic function with left ventricular ejection fraction of 49% using the three-dimensional Simpson's method (B); transesophageal echocardiography allowed better characterization of the mechanical aortic prosthesis, excluding valve dysfunction (C and D).

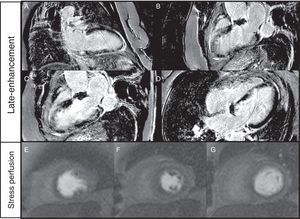

During hospitalization there was no recurrence of pain, and a final diagnosis of non-ST elevation acute myocardial infarction was made; it was hypothesized that a thrombus formed on the LAD plaque could have transiently limited coronary blood flow. She was discharged home after six days of hospitalization on medication with aspirin 100 mg once daily, warfarin, atorvastatin 40 mg once daily, bisoprolol 2.5 mg once daily, and transcutaneous nitroglycerin 5 mg 12 hours a day. Cardiac contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) was scheduled for two weeks later which revealed inferoseptal transmural infarct scar, inferior and inferolateral subendocardial infarct and mid-basal ischemia in the anterior and anterolateral walls (Figure 4).

(A–G) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Late-enhancement gadolinium evaluation showed transmural infarct scar in the inferoseptal wall and subendocardial infarct in the inferior and inferolateral walls (A–D). Ischemia (reversible perfusion defect) was documented in the mid-basal segments of the anterior and anterolateral walls (E–G).

One month after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the cardiac intensive care unit because of recurrent chest pain with hemodynamic instability; her blood pressure was 70/44 mmHg and her heart rate was 125 bpm. Marked ST depression in all precordial leads and severe global left ventricular dysfunction were present (Figure 1C).

Despite her arterial hypotension, intravenous nitroglycerin was initiated with relief of chest pain, ST-T segment normalization and increase in blood pressure. Aspirin and bisoprolol were stopped and she was started on diltiazem 200 mg bid orally. After adequate informed consent had been obtained, pharmacological provocation testing for coronary artery spasm was performed with intracoronary injection of acetylcholine (ACh). After control coronary angiography, ACh was administered in a stepwise manner into the LAD (20–100 μg) and the right coronary artery (RCA) (20–50 μg) over a period of 20 seconds with a 3–5 min interval between injections. Coronary angiography was performed after each injection of ACh and when chest pain and/or ST changes were observed. At baseline coronary angiography showed no new stenosis or coronary blood flow impairment; after ACh injection into the LAD chest pain, ST-segment depression, LAD TIMI blood flow of 1 and transient grade 3 atrioventricular (AV) block were documented. Intracoronary administration of nitrates reversed the coronary spasm and AV conduction disturbances. Twenty minutes later, chest pain and ischemic ST changes recurred; response to nitrate infusion was poor and cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity occurred. Advanced life support was maintained for 32 minutes without return of spontaneous circulation.

Clinical and angiographic diagnosisVasospastic angina (left anterior descending coronary artery spasm).

DiscussionCoronary artery spasm is one of the important functional abnormalities of the coronary arteries and plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of a wide variety of ischemic heart disease and arrhythmic events. Provocative testing for coronary artery spasm is useful for the diagnosis of vasospastic angina (VSA). However, these tests are thought to have a potential risk of irreversible ischemia and arrhythmic complications.

Definition and pathology of vasospastic anginaVSA is a condition in which a relatively large coronary artery transiently exhibits abnormal contraction. The initial description of VSA considered vasomotor instability as a key mechanism.1 Prinzmetal et al. described a variant form of angina, which was later confirmed to be coronary spasm, and characterized by symptoms at rest (not during exertion) with ST elevation (not depression) on the ECG; it usually occurs in the early hours of the morning during depressed vagal tone and is associated with occlusion or near occlusion (>90% stenosis) of a focal proximal coronary segment on angiography.2 Currently, it is accepted that both ST-segment elevation and depression can occur. In cases of a coronary artery completely or nearly completely occluded by spasm, transmural ischemia can occur and in turn cause anginal attacks with ST elevation on the ECG. However, if a coronary artery is partially occluded or diffusely narrowed by spasm, or if it is completely occluded by spasm but sufficient collateral flow has developed distally, nontransmural ischemia occurs, causing anginal attacks with ST depression on the ECG.3,4

The precise mechanism responsible for coronary spasm remains largely unknown; evidence suggests that the pathogenesis of coronary spasm differs from that of coronary atherosclerosis-based stenosis. Previous studies described different patterns of angiographic changes during the provocation test, including focal and diffuse spasm.3–5 The diffuse spasm pattern is reported to be more common in Japanese than Caucasian patients (20% vs. 7%).6,7 The focal spasm pattern is more frequently associated with a thicker coronary artery intima-media layer than the diffuse pattern and is induced in a setting of relatively advanced atherosclerotic lesions.8 Older age, current smoking, high levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and elevated serum levels of remnant lipoprotein have been also identified as significant risk factors for VSA.9–11

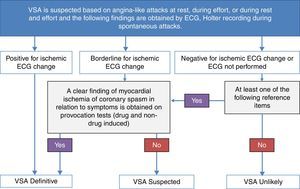

Diagnostic criteriaCurrent guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology12 and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology13 hardly address the issue of VSA diagnosis and treatment since no large-scale clinical studies of this condition have been performed. The scientific committee of the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS)4 has drawn up guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of VSA. A flowchart for the diagnosis of VSA proposed by the JCS is illustrated in Figure 5.

Flowchart for the diagnosis of vasospastic angina (VSA). VSA can be diagnosed when anginal attacks disappear quickly upon administration of nitroglycerin, and at least one of the following reference items is present: (1) attacks appear at rest, particularly between night and early morning; (2) marked diurnal variation is observed in exercise tolerance (in particular, reduction of exercise capacity in the early morning); (3) attacks are accompanied by ST elevation on the ECG; (4) attacks are induced by hyperventilation (hyperpnea); (5) attacks are suppressed by calcium channel blockers but not by beta-blockers. VSA is considered definite if the patient has clearly ischemic changes on the ECG during typical attacks, or positive non-drug-induced coronary spasm provocation test (e.g. hyperventilation or exercise test), or positive drug-induced coronary spasm provocation test (e.g. acetylcholine or ergonovine provocation test). The patient is considered to have suspected VSA when the ischemic changes on the ECG during attacks are borderline and no clear finding of myocardial ischemia or coronary spasm is obtained in any examination. VSA is considered unlikely if ischemic changes were absent on the ECG or the ECG was not performed during the attack and none of the previous conditions was present. (Adapted from JCS Joint Working Group4).

According to the JCS guidelines, VSA is considered definite if the patient has clearly ischemic changes on the ECG during typical attacks, or a positive non-drug-induced coronary spasm provocation test (e.g. hyperventilation or exercise test), or a positive drug-induced coronary spasm provocation test (e.g. acetylcholine or ergonovine provocation test). The patient is considered to have suspected VSA when the ischemic changes on the ECG during attacks are borderline and no clear finding of myocardial ischemia or coronary spasm is obtained in any examination. VSA is considered unlikely if ischemic changes were absent on the ECG or the ECG was not performed during the attack and none of the previous conditions was present.

Pharmacological provocation testing performed during coronary angiography is recommended in patients in whom VSA is suspected based on symptoms, but who have not been diagnosed with coronary spasm by non-invasive evaluation. It is contraindicated in patients considered at high risk of suffering a life-threatening complication of induced coronary spasm (e.g. patients with left main coronary trunk lesions, multivessel disease or untreated congestive heart failure).4

Usefulness and safety of provocative testsPharmacological (i.e. ergonovine or ACh) and non-pharmacological (i.e. hyperventilation) provocation tests of coronary spasm during coronary angiography are established as a useful tool for the diagnosis of VSA, because coronary spasm develops transiently and it is not easy to document spontaneous attacks in a clinical context. The first provocation test with ergonovine during coronary angiography was performed at the Cleveland Clinic in 1973.1 Subsequently Specchia et al. and Yasue et al. reported the use of ACh for the induction of coronary spasm.

The intracoronary injection of ACh is known to have high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (99%) for the diagnosis of VSA; however, these tests are thought to have a potential risk of serious complications, including ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), and bradyarrhythmias.1 Recently, the safety and clinical implications of provocation tests were evaluated in a total of 1244 VSA patients from the nationwide multicenter registry of the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association.6 The provocation tests were performed with either ACh (57%) or ergonovine (40%), and VT/VF and bradyarrhythmias developed in 3.2% and 2.7%, respectively. Overall, the incidence of arrhythmic complications was 6.8%, a comparable incidence to that during spontaneous angina attack (7.0%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that diffuse RCA spasm and the use of ACh had a significant correlation with provocation-related VT/VF. Mixed (focal plus diffuse)-type multivessel spasm had an important association with major adverse cardiac events in multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.84; 95% confidence interval 1.34–6.03, p<0.01), whereas provocation-related arrhythmias did not. The authors concluded that provocation tests have an acceptable level of safety and usefully information for the risk prediction of VSA patients. A previous study indicated that baseline QT dispersion was significantly greater in VSA patients complicated by ventricular arrhythmias. Slower infusion of provocation agents may reduce the incidence of arrhythmic complications, although excessively slow infusion of ACh may also lead to underestimation of the prevalence of coronary spasm.

Conclusions and areas of uncertaintyThe use of provocation tests for the detection of abnormal coronary vasomotion in patients with anginal symptoms but angiographically unobstructed coronary arteries not only provides reassurance to the patient that a cause for the symptoms has been found, but also enables the physician to initiate appropriate medical therapy (calcium channel blockers and nitrates) aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality. This may also have important implications for healthcare systems, because most healthcare-related costs in patients with unobstructed coronary arteries are due to recurrent or ongoing angina pectoris. Although rare, the risks of provocation tests are potentially fatal and they should be avoided in patients with left main disease, multivessel disease, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or acute heart failure. Future studies are needed to assess the safety and effectiveness of intracoronary ACh provocation testing in a contemporary cohort of Caucasian patients with unobstructed coronary arteries.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis work has no funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.