Left ventricular noncompaction is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by excessive left ventricular trabeculation, deep intertrabecular recesses and a thin compacted layer due to the arrest of compaction of myocardial fibers during embryonic development. We report the case of a young patient with isolated left ventricular noncompaction, leading to refractory heart failure that required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation followed by emergency heart transplantation.

A não compactação do miocárdio é uma anomalia congênita rara, definida por excessiva trabeculação do ventrículo esquerdo, profundos recessos intertrabeculares e uma camada compactada fina, devido à interrupção do processo de compactação das fibras miocárdicas durante a fase embriogênica. Relatamos um caso de uma paciente jovem com miocárdio não compactado isolado evoluindo para insuficiência cardíaca refratária, com necessidade de uso de oxigenação por membrana extracorpórea seguido de transplante cardíaco de emergência.

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by excessive left ventricular (LV) trabeculation, deep intertrabecular recesses and a thin compacted layer due to the arrest of compaction of myocardial fibers during embryonic development. It can also be acquired through cardiac remodeling, mainly in young athletes or in pregnancy and sickle cell anemia.1 LVNC is usually associated with other congenital cardiac malformations.1,2 The cause of isolated LVNC is unknown and no factor has yet been identified to explain the arrest of myocardial compaction.1,3

LVNC is associated with a wide range of clinical manifestations; while some patients may be asymptomatic, symptoms can appear at any age, including heart failure (HF), thromboembolic phenomena and cardiac arrhythmias; the disease has a poor prognosis. LVNC is found in 0.81 per 100000 infants/year and 0.12 per 100000 children/year, and has a prevalence of 0.014% in adults.1,3 There are no specific histological findings, other than fibrosis.4

We describe the case of a patient with isolated LVNC who developed refractory HF and required emergency heart transplantation.

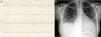

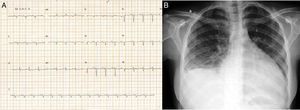

Case reportTSA, a 14-year-old white girl, born and resident in the municipality of Barueri, São Paulo, Brazil and a handball player, whose father had died six months previously due to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (no anatomopathological study was performed), sought emergency medical assistance at the Hospital Dante Pazzanese de Cardiologia due to worsening dyspnea over the previous 15 days. On admission she reported dyspnea at rest. Physical examination showed her to be in reasonable general condition, conscious and oriented. Pulmonary auscultation revealed rales in the lower third of both lungs and cardiac auscultation showed a gallop rhythm (B3), with no murmurs; other observations were lower limb edema (3+/4+), blood pressure 100/70 mmHg, and liver palpable 7 cm below the right costal margin. The 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1A) showed sinus rhythm, narrow QRS complex, low-voltage QRS in the frontal plane, left atrial overload, signs of right atrial overload, diffuse ventricular repolarization abnormalities and right axis deviation (−170°) but no criteria for left posteroinferior hemiblock. The chest X-ray revealed a significantly enlarged cardiac silhouette (Figure 1B), while echocardiography (Figure 2A) showed left atrium 38 mm, considerably enlarged right atrium, LV dilatation (60 mm×68 mm), LV ejection fraction 25%, superior vena cava 14 mm, tricuspid regurgitation with annular dilatation (30 mm), and moderate right ventricular systolic dysfunction. A rounded hyperdense mass measuring 17 mm×14 mm was observed in the left atrium, indicating a thrombus, a small pericardial effusion, and moderate pulmonary hypertension (40 mmHg). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 2B) revealed severe biventricular dysfunction with thickened myocardium, mainly in the LV anterior wall and apex, with a ratio of noncompacted to compacted layers of 5.5, but no late enhancement suggestive of myocardial fibrosis. LV size was 67 mm×71 mm, LV ejection fraction 8%, and right ventricular ejection fraction 2%. No coronary angiography, Holter ECG or electrophysiological studies were performed. Laboratory tests showed normal cardiac enzymes, NT-proBNP of 6850 pg/ml, and negative serology.

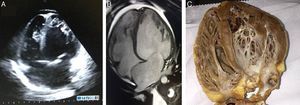

Echocardiography (A) and magnetic resonance imaging (B), 4-chamber long-axis view in diastole, showing isolated left ventricular noncompaction, together with right and left ventricular dilatation. Ratio of left ventricular noncompacted to compacted layer is 5.5; (C) macroscopic anatomical study of patient's native heart in 4-chamber view.

Dobutamine 5 μg/kg/min was begun, together with systemic anticoagulation with full-dose enoxaparin. Pulmonary vascular resistance was calculated at 1.7 Woods units using a Swan-Ganz catheter.

The patient developed low cardiac output, atrial fibrillation with high ventricular response (heart rate 160 bpm), worsening level of consciousness, hypotension and seizures, requiring orotracheal intubation and synchronized electrical cardioversion. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was begun. The patient developed multiple organ failure (acute renal failure requiring dialysis and liver failure with changes in transaminases and coagulation parameters, thrombocytopenia and elevated bilirubin). Blood cultures were negative. The patient was put on the priority list for heart transplantation.

After 72 h of ECMO, she underwent heart transplantation, with no complications during the procedure. Acute renal failure persisted, requiring hemodialysis for three days, followed by improvement in the patient's coagulopathy and organ dysfunction.

Ventricular assist therapy (intra-aortic balloon or ECMO) was not required after surgery. Anatomopathological study of the explanted heart (Figure 2C) showed hypertrophy and mild degeneration of myocardial fibers. The patient remained stable, with no further complications, and was discharged in good general condition. She is being followed as an outpatient.

DiscussionIsolated LVNC is a relatively rare entity that mainly affects males2 (56%–82% of patients in the four largest series). Both familial and sporadic forms have been described. Most patients were children in the first published study of isolated LVNC and familial recurrence was observed in half the patients.2 In the largest series yet reported, familial recurrence was found in 18% of cases, although most authors stress that this is probably an underestimate due to ineffective triage.4

With regard to the genetic bases of LVNC, mutations in various genes coding for sarcomere, cytoskeletal and nuclear membrane proteins have been identified, including G4.5, TAZ, PRDM16, TNNT2, LDB3, MYBPC3, MYH7, ACTC1, TPM1, MIB1 and DTNA, many of them associated with dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.1,5,6

For diagnosis, echocardiography is the first-line exam for patients and their relatives, but there are differences between the criteria used. For Chin et al.2 diagnosis is based on a ratio of <0.5 between the distance from trough to peak of a trabecular recess. Another parameter used is LV free wall thickness at end diastole.2,7 According to Petersen et al.1,8 the most important criterion is the ratio of noncompacted to compacted myocardium, a ratio of >2 between the thickness of the noncompacted and compacted layers in systole being considered diagnostic. Other findings include systolic and diastolic dysfunction.1 MRI can provide additional anatomical and functional information on the wall motion of noncompacted versus compacted segments and fibrosis.1 However, distinguishing between pathological LVNC and physiological hypertrabeculation is a diagnostic challenge that is increasingly encountered with advances in imaging techniques.9

Given the high prevalence of malignant arrhythmias in LVNC, Holter monitoring should be performed at least annually, and electrophysiological study and/or prophylactic implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator should be considered. Competitive sports are to be avoided,1,10 since sudden death accounted for around half of deaths in the largest series of isolated LVNC.10

Studies show that asymptomatic patients have a better prognosis.1,2 At the onset of symptoms (such as HF, embolism or arrhythmia) treatment should be initiated irrespective of the underlying diagnosis and tailored to each patient. There are no specific guidelines for the treatment of LVNC.

In cases of treatment failure, heart transplantation may be the only option,10 as in our patient, who rapidly developed refractory HF.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of isolated LVNC can be confirmed by two-dimensional echocardiography or MRI, the results of which generally correspond to macroscopic morphological findings on autopsy. Although it is uncommon, the diagnosis should be considered in young patients with unexplained ventricular failure. LVNC represents a highly specific phenotype that is associated with increased risk for progressive HF, sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmias and embolic events.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Meneguz-Moreno RA, Rodrigues da Costa Teixeira F, et al. Miocárdio não compactado isolado evoluindo para insuficiência cardíaca refratária. Rev Port Cardiol. 2016;35:185.e1–185.e4.