In a recent Editorial Comment in this Journal1 on my article on the implementation of a regional system for the emergency care of acute ischemic stroke,2 Carlos Morais states “There is still a long way to go in terms of optimizing patients’ access to specialized health centers … for which it is necessary to implement dedicated clinical pathways within institutions.”

This is precisely the reasoning behind the project implemented in the North region of Portugal that is presented in the article and that has had excellent results (Figure 1). Its success springs from campaigns to raise public awareness of the signs of stroke; specific training for members of the pre-hospital emergency response team; the establishment of acute stroke teams on call 24 hours a day in all emergency departments classified as ‘general’ or ‘medical and surgical’; priority routing of stroke patients for access to imaging facilities and laboratory testing in the emergency department; permanently available computed tomography imaging and reporting; and the existence of ward beds designated for acute stroke patients. The number of patients undergoing thrombolysis increased by over 300% in four years, which unequivocally demonstrates greater and better access.

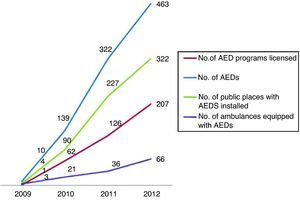

Prof. Morais also quotes another article by me in the same issue of the Journal, on the implementation of a national automated external defibrillator (AED) program in Portugal,3 and states that the program “has at times been subject to excessive centralization, over-control and legislative inflexibility, which has made its large-scale implementation in public places more difficult … incentives should be established for companies and societies, state and non-state, which decide on their own initiative to participate in the program by acquiring AEDs and placing them prominently in busy places.” He cites the example of Brescia, Italy, which shows that “a strategy of placing AEDs in public places with large concentrations of people, to be used by volunteers with minimal training or even laypersons, is safe and associated with better survival of victims of cardiac arrest.”4 But he overlooks the important results presented in the article: an exponential increase in the number of people trained in basic life support and AEDs and in the number of public places with large concentrations of people that during the period of study have been provided with AEDs and people trained in their use (Figure 2). At the end of 2010 there were around 100 ambulances equipped with AEDs; by the end of 2012 there were 442, while the number of public places with AEDs rose from four in 2010 to 322 by the end of 2012, including airports, shopping centers, sports and leisure venues, hotels, etc., representing an increase of over 8000% in two years. The article on the experience of Brescia4 describes a similar process to the one in our study: defibrillation was originally a medical act, then legislation was passed and defibrillators were introduced into ambulances, and finally AEDs are placed in public places where they can be used by people who are not medically qualified first responders but are duly trained and certified in their use. In Brescia 49 AEDs were installed in public places, as opposed to 463 in Portugal during the same period, and 366 individuals were trained, compared to 6133 trained in Portugal by the end of 2012.

With regard to the question of legislation, it is important to note the chronology of developments in this area. Until 2009 there was no relevant legislation, defibrillation being exclusively the responsibility of physicians; in that year this responsibility could be delegated to non-medical personnel (a considerable advance),5 and in 2012 the legislation was revised to make provision of AEDs in large and busy public places a legal obligation.6 A proposal has also been presented to the Government to make basic life support part of the curriculum in secondary schools.

It is desirable, and arguably inevitable, that when there is sufficient momentum in society to support such a move the next legislative step will be to further liberalize the use of AEDs in public places, reducing centralized control over the process, so that any citizen – even if not certified – can use them. But for this to happen, in my opinion the previous steps described above were essential.

In truth, the good results presented in the article show, as the author of the editorial admits, that the path followed up to now has been at least acceptable and compares favorably with experiences and results in other countries.

The strategy suggested by the author of the editorial on the two articles is thus precisely the one followed by this author, as clearly explained in both articles.

Please cite this article as: Soares-Oliveira M. Lutar contra a mortalidade por doenças cardiovasculares: um desafio para a sociedade – apenas depois dos profissionais de saúde definirem o seu rumo. Rev Port Cardiol. 2014;33:817–818.