Traditionally, when cohorts and trials in cardiovascular medicine have been published, the data have been presented for the entire population, assuming homogeneity among patients with the disease under investigation. However, with the advent of personalized medicine, we have come to realize that cardiac patients, even those with the same diagnosis, are in fact quite diverse. First and foremost, males and females are not alike, but also younger and elderly patients differ, as do those with different ethnic backgrounds.

Since the landmark publication by the US Institute of Medicine, now the National Academy of Medicine, “Does Sex Matter?” in 2001,1 sex as a biological variable has been more and more incorporated into medical research design and publications. Indeed, the main message of that seminal publication was that biological sex influences health and disease “from womb to tomb”.2 The National Academy of Medicine added the clarifying statement that in the English language sex refers to the biological aspects and gender to the cultural aspects of this issue. It is now obvious that the sex distribution of patient populations in studies, registries and trials will affect the results. For instance, women are more prone to developing heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, while heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is more common among males.3,4 Furthermore, men more commonly have obstructive coronary artery disease, particularly among younger age groups, while females more often suffer from ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease, just to mention a few examples.5 Thus, reporting data not only overall, but also separately according to sex, is scientifically meaningful. In fact, it may affect guideline recommendations and in turn outcomes, in efforts to personalize management of cardiac conditions.

In this issue of the Journal, David Roque and colleagues discuss the features of the woman's heart in almost 50 000 patients with acute coronary syndromes.6 Out of the 49 113 patients, 14 177, or 28.9%, were female. Of note, all cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia were more common in females, as was presentation as non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) with atypical symptoms. Surprisingly, and in contrast to other registries of this type, women were younger than men.

Of clinical concern is the fact that women had longer times from symptom onset to revascularization and they less often underwent thrombolysis or primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Indeed, this is not in line with the latest ESC guidelines for NSTEMI,7 nor with the more recent guidelines on revascularization.8 There may be several reasons for this. First, women presented more often with atypical symptoms. Hence, the physician at first contact might have falsely suspected a non-cardiac cause of the symptoms, rather than NSTEMI. Second, even females who underwent angiography more often had normal coronary arteries or less than 50% lesions. It must be assumed that this was mainly assessed by eye-balling rather then using fractional flow reserve,9 a technique that has been shown to be more sensitive and specific than visual assessment of the coronary circulation.10 However, women are also known to suffer more often from microvascular disease, and as such they may have presented more often with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA).11 Overall, MINOCA affects around 5% of all patients with acute coronary syndromes and is associated with significant major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), albeit less so than true ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or NSTEMI.12 Unfortunately, the prevalence of Takotsubo syndrome, a condition primarily affecting postmenopausal women,13 was not recorded, probably because most operators do not perform ventricular angiography in the presence of non-obstructive coronaries. However, in series in which this was regularly performed around 3-4% of patients with acute coronary syndromes suffered from Takotsubo syndrome. Lastly, there may be an unconscious gender bias by treating physicians, but with the feminization of medicine and now also cardiology this is not likely to represent the major factor.

Once hospitalized, women also had more MACE, with double the mortality, and an increased risk of bleeding, heart failure, atrial fibrillation and cardiogenic shock. Higher mortality in women with acute coronary syndromes is well known,14 and has been mainly attributed to their greater age at presentation. Indeed, when adjusted for age, mortality was not higher in women in some more recent series adhering strictly to current guidelines.15 However, in the present Portuguese series, women were surprisingly younger rather than older. Possibly, the higher event rate in women could be related to the much higher risk factor burden in females compared to males. Unfortunately, infarct size is not available in this registry, which would help to understand this difference better, but the higher brain natriuretic peptide levels at presentation would be compatible with larger infarcts in women, leading to an increased prevalence of heart failure and cardiogenic shock. As such, women more often required diuretics, inotropes, non-invasive and invasive ventilation and temporary pacemaker implantation. Of note, while 96.7% of males received dual antiplatelet therapy, only 87.2% of women received this guidelines-recommended treatment, which may have contributed to their higher in-hospital event rate.16,17

Furthermore, although antiplatelet therapy was less intense in women than in males (87.2% vs. 96.7%), women had more bleeding, which is known to adversely affect outcomes.18 Of note, the use of different glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was comparable and these drugs were used in almost all patients. As women are usually smaller and have a lower bodyweight and lower blood volume than men, the actual concentration of these antagonists may have been higher in females than in males and in turn their propensity to bleed might have been higher, thereby facilitating bleeding.19

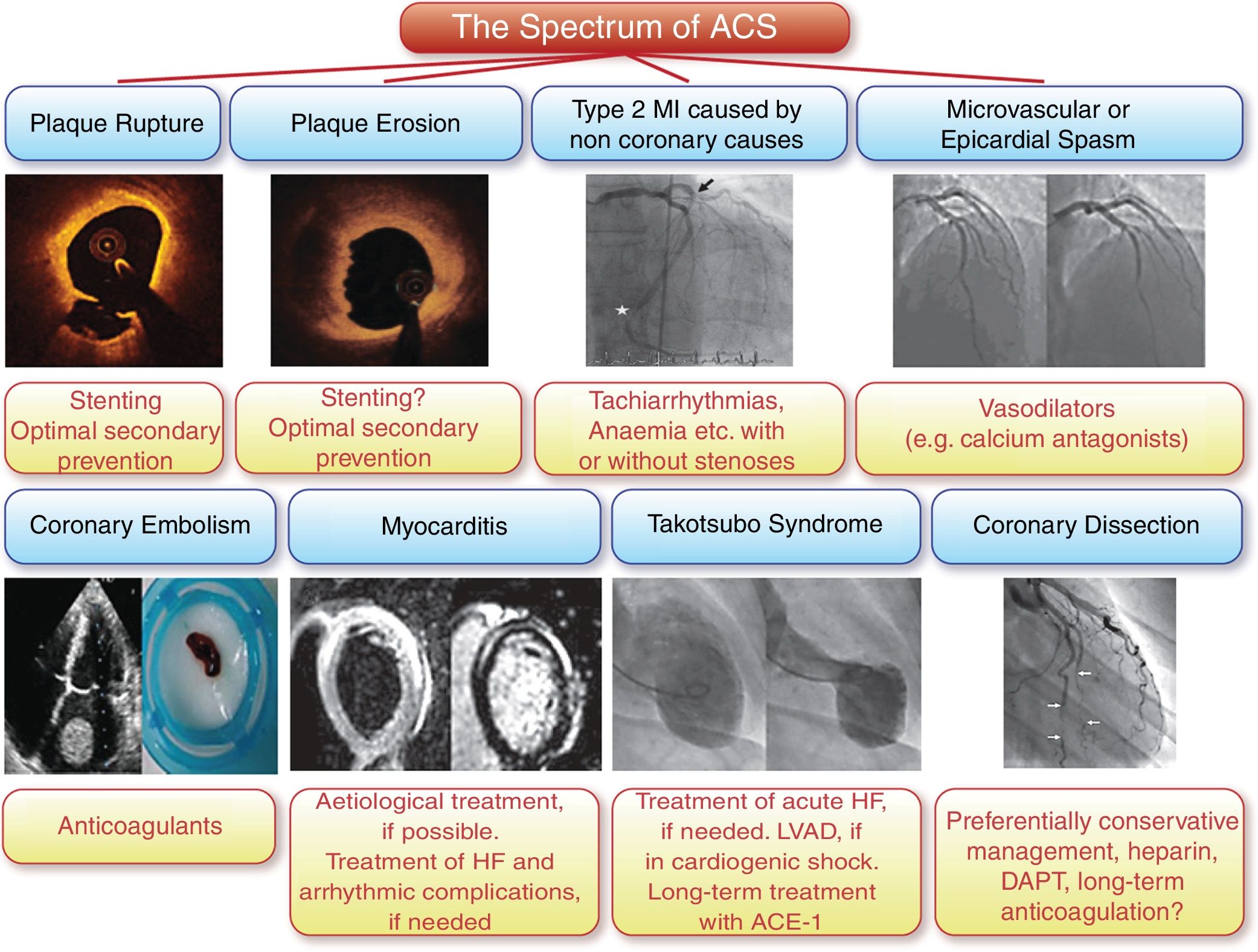

In summary, the diversity of cardiac patients remains an underestimated issue. We should consider not only sex and gender as addressed in this important study in patients with acute coronary syndromes, but also differences in presentation, management and outcomes of younger and elderly patients20 as well as the important role of ethnicity.21 In acute coronary syndrome this issue is particularly important due to the still substantial mortality associated with this condition. Importantly, the spectrum of different presentations of acute coronary syndromes is indeed different between the sexes: women present more often with NSTEMI, more commonly have endothelial erosion rather than plaque rupture as the underlying cause,22 particularly among younger female smokers,23 and finally Takotsubo syndrome24 and spontaneous coronary dissection25 are typical female presentations of acute coronary syndromes (Figure 1).26 Let us therefore consider patient diversity on a daily basis, for the sake of patients and medicine at large.

The spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Compared to men, women present more often with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, endothelial erosion is more common in younger female smokers, and Takotsubo syndrome and spontaneous coronary dissection are typical female presentations of acute coronary syndromes (reproduced with permission from Banning et al.26). ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; HF: heart failure; LVAD: left ventricular assist device; MI: myocardial infarction.

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.