The authors describe a case of a patient admitted with a pre-syncopal episode and precordial discomfort, and whose cardiac ultrasound performed in the Emergency Room was suggestive of Pulmonary Embolism. The patient was submitted to fibrinolytic therapy after cardiac arrest. The computerized tomography done after this episode not only confirmed the presence of pulmonary embolism but had also shown a Stanford Type B Aortic Dissection. The option was to maintain the therapeutic anticoagulation, having the patient evolved favourably.

Os autores descrevem um caso de uma doente admitida após episódio pré-sincopal associado a precordialgia e cujo ecocardiograma sumário feito no Serviço de Urgência demonstrou alterações compatíveis com tromboembolismo pulmonar, tendo a doente sido submetida a terapêutica fibrinolítica, após episódio de paragem cardiorrespiratória. Na angiotomografia de tórax feita posteriormente para confirmação diagnóstica demonstra-se a presença não só de trombos no nível da artéria pulmonar, mas também de disseção da aorta Stanford B, tendo-se optado pela manutenção de anticoagulação terapêutica e a doente evoluído de forma favorável.

Aortic dissection (AD) has been viewed as a contraindication to the use of anticoagulants, due to the high risk of bleeding in the event of aortic rupture or an urgent/emergent need for surgery. However, given the described state of hypercoagulability associated with this condition1 and the recommendation for rest, the risk of thrombotic phenomena in these patients cannot be ignored. Specific circumstances may lead to a need to use therapeutic anticoagulation; in these cases an assessment of the risk-benefit profile is essential and treatment decisions must be patient-tailored.

Clinical caseWe present the case of a 66-year old female patient with a known medical history of hypertension, dyslipidemia and osteoarticular disorder, medicated with statins, opioids (metamizole magnesium) and antihypertensives (olmesartan medoxomil and amlodipine).

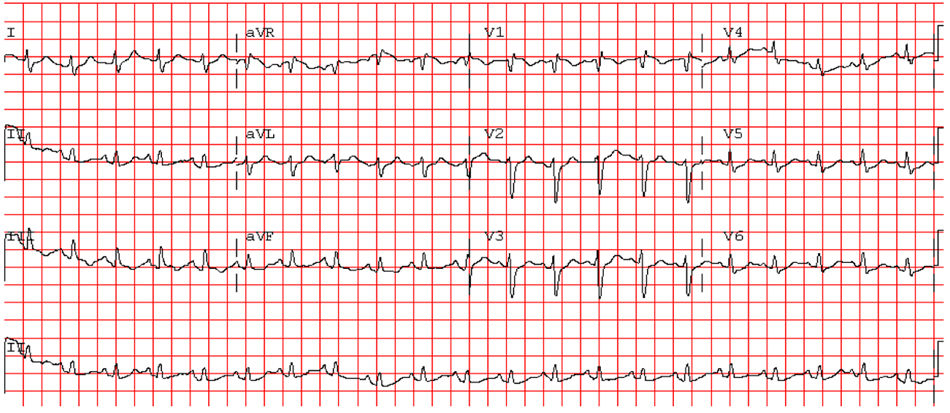

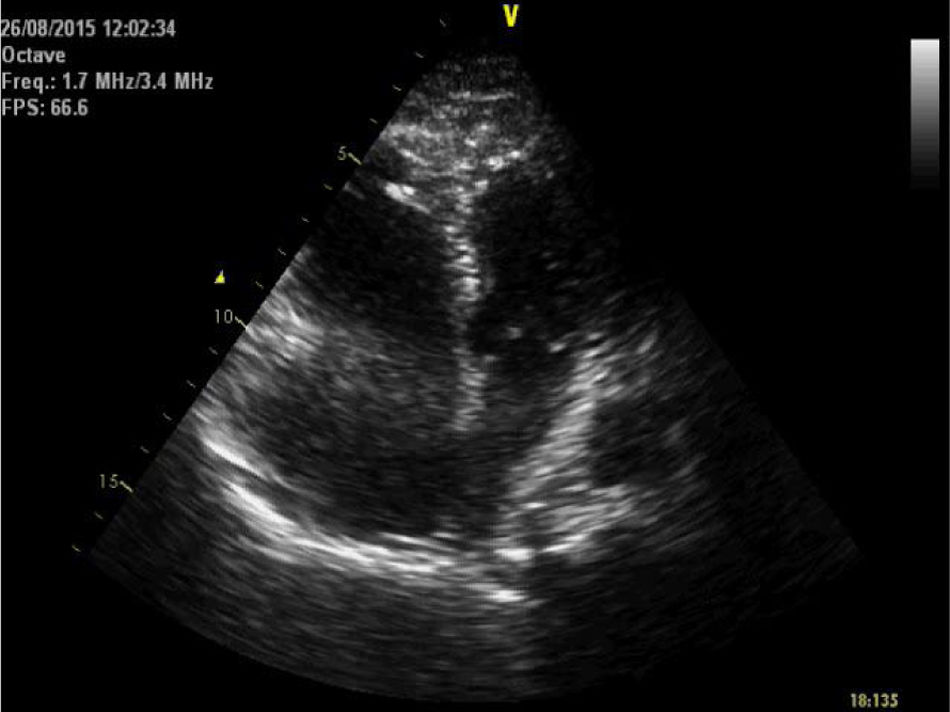

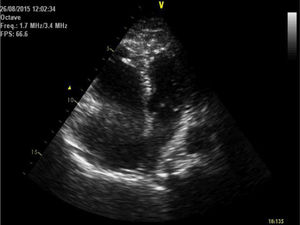

She was brought to the emergency room (ER), having been found cyanotic and diaphoretic at home following a fall. At the time she reported sharp chest pain, radiating to the back. Hypotensive (blood pressure was only taken in the left arm), presenting with tachycardia and polypnea; lung auscultation demonstrated no adventitious sounds and cardiac auscultation revealed rhythmic, tachycardia heart sounds with a systolic ejection murmur. No induration of the calf muscles or Homans’ signs in the legs. She progressed to respiratory fatigue and pulseless electrical activity. Spontaneous circulation returned after two cycles of advanced life support (ALS); invasive mechanical ventilation was required. The electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia, right axis deviation, incomplete right bundle branch block and T wave inversion in lead 3 (Figure 1). The transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed a D-shaped left ventricle, preserved systolic function, dilated right ventricle with longitudinal systolic dysfunction (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) 14 mm) and moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was estimated at 35 mmHg. No visible thrombi were observed in the pulmonary artery branch (Figure 2). Due to suspected pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) with hemodynamic instability (obstructive shock), we began fibrinolytic therapy with tenecteplase (45 mg) and inotropic support with noradrenaline.

Noteworthy test results include: D-dimers 13574 ng/ml (<500 ng/ml), troponin I 0.05 ng/ml (<0.02 ng/ml) and pro-brain natriuretic peptide 1211 pg/ml (<200 pg/ml). Hemoglobin at admission was 12.1 g/dl. The chest x-ray performed upon admission did not show significant changes, notably mediastinal widening or an increased cardiothoracic ratio.

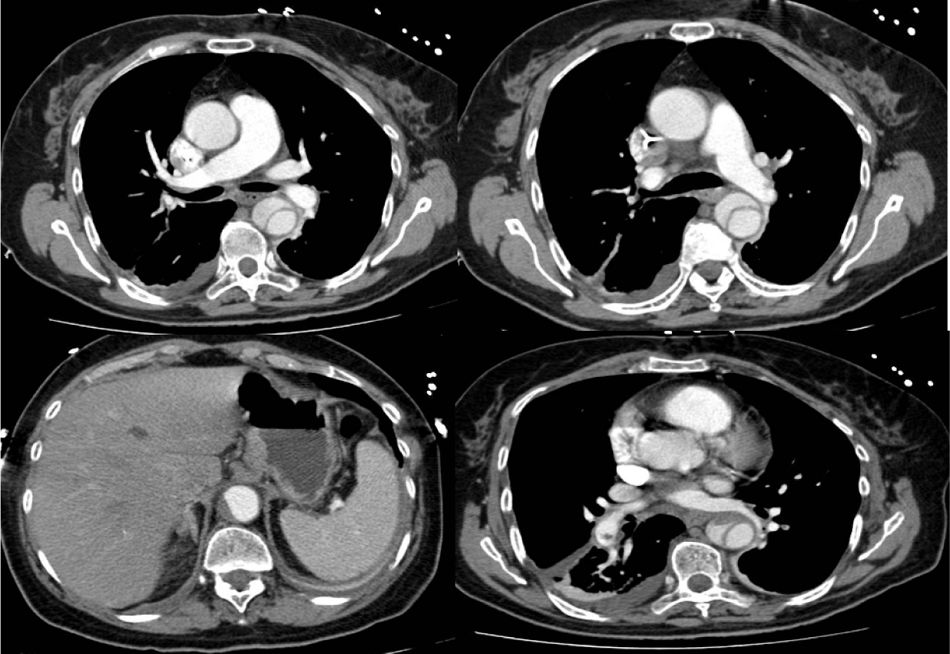

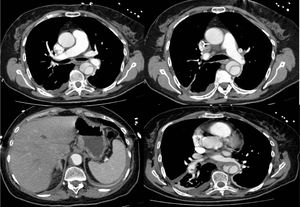

Following hemodynamic stabilization, approximately 12 hours after fibrinolysis, a computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed, showing a Stanford type B dissection of the thoracic aorta, beginning in the descending thoracic aorta, immediately after the aortic arch and ending in the abdominal aorta above the area where the celiac trunk arises. It revealed partial thrombosis of the lumen in the abdominal portion. Permeability of the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, renal arteries and iliac arteries was maintained. In the basal segments of the pulmonary artery, a small non-occlusive, endoluminal, eccentric thrombus, measuring approximately 9 mm along the major axis, was observed, and also a small thrombus adhering to the left branch of the pulmonary artery (Figure 3).

The patient progressed favorably and in under 24 hours inotropic and ventilatory support were suspended. During admission, a Doppler ultrasound of the lower limbs and hypercoagulability testing were performed. No changes were recorded. Accordingly, after multidisciplinary discussion with the vascular surgery department, 48 hours after fibrinolysis, anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin was initiated at a therapeutic dose (1 mg/kg every 12 hours) and the patient's blood pressure was managed with carvedilol and captopril. After 96 hours, the CTA was repeated, showing overlap and excluding progression of the dissection. In this setting, the decision was made to begin rivaroxaban 15 mg every 12 hours, which the patient took for 21 days, after which she was anticoagulated with rivaroxaban 20 mg, once a day.

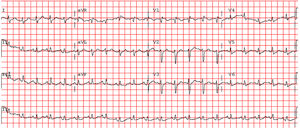

No complications were documented during admission, notably episodes of chest pain or bleeding. She was transferred to a cardiac nursing floor, discharged after 10 days and referred for assessment at a vascular surgery and cardiology outpatient clinic. Hb and hematocrit values remained stable throughout hospital admission, with a nadir of 10.5 g/dl while hospitalized and 10.9 g/dl at discharge. A year after the initial event, she was clinically stable with no new hospital admissions. The one-year reassessment TTE showed preserved global left ventricular systolic function, an undilated right ventricle with good systolic function (TAPSE 19 mm), minimal tricuspid regurgitation and PASP estimated at 28 mmHg; no changes to the aortic root, initial segment of the ascending aorta, aortic arch and supra aortic branches; a tortuous descending thoracic aorta and abdominal aorta with ill-defined limits and intraluminal images. Using this technique, it is not possible to affirm conclusively whether these findings correspond to images of flap and/or dissection. The reassessment CTA showed some overlap with the initial testing, no evidence of the dissection extending distally or proximally, and the partial thrombosis of the false lumen was maintained.

DiscussionAmong the most difficult differential diagnoses in patients presenting with chest pain are PTE and AD. Echocardiograms may play an essential role when determining the course and approach, especially where there is hemodynamic instability.

Reperfusion therapy with fibrinolytic agents is indicated as a class I, level of evidence B recommendation of the European Society of Cardiology2 for PTE with hemodynamic instability unless contraindications are present. However, it is only possible to detect distal dissection of the aorta via echocardiogram in 70% of patients.3

Concomitant PTE and AD are rarely described in the literature and the approach for these patients is open to discussion. Gupta et al.4 described the case of a patient admitted to an ER with dyspnea, whose CTA revealed the coexistence of PTE and abdominal AD. However, the authors did not describe the immediate or long-term therapeutic approach. Although it is rare, concomitant PTE and Stanford type A AD is reported much more frequently in literature. Leu et al.5 reported a case of PTE and Stanford type A AD, in which the initial therapeutic approach of surgery was rejected by the patient. The authors opted for conservative management; anticoagulation using unfractionated heparin (UFH), due to the possibility of almost immediate reversal. Sudden death occurred on the eighth day of admission. The coexistence of the two diseases was also reported in 2013,6 but due to the very high surgical risk, a conservative strategy was adopted and the patient progressed to tetraparesis and kidney failure. She was discharged on request to a continued care unit.

Stanford type B AD as a complication of cardiac compressions was first described by Oren-Grinberg et al.,7 and the cause-effect relationship was established due to a computed tomography having been performed pre- and post-cardiac arrest. However, in this case, the ALS maneuvers lasted for longer (30 minutes) than the case we describe here, thus making this hypothesis seem improbable.

The use of anticoagulation therapy in our patient was permitted after multidisciplinary discussion, given that this conduct in patients with AD is rarely described. Tomaszuk-Kazberuk et al.8 reported a case of Stanford type B AD treated conservatively, permitted following acute myocardial infarction and managed without prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulant treatment. An elective computed tomography showed the presence of PTE and the authors chose to begin anticoagulant therapy with UFH and long-term therapy with an oral anticoagulant. The patient progressed favorably. The guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology on PTE2 recommend UFH in the first few hours following fibrinolysis due to its potential for rapid reversal. However, in this case, due to the concomitant AD the decision was made only to begin parenteral anticoagulation 48 hours after fibrinolysis.

It is impossible to establish the temporal relationship between the two diseases in this setting. The initial clinical presentation (type of pain) seems suggestive of AD, but the initial echocardiogram and TTE pointed to PTE. The authors believe that in this setting the two diseases occurred simultaneously or temporally very close to each other, or the patient may already have had a previously undocumented AD.

It has been described that patients with AD present a state of hypercoagulability in an acute phase, resulting in a high risk of venous thromboembolism. However, anticoagulation therapy may also cause the dissection to worsen, resulting in the recanalization of the false lumen and re-dissection, leading to the possible indication of stent grafting, depending on anatomical location.1 Stent grafting is controversial and the guidelines only give a class IIA, level of evidence B3 recommendation in uncomplicated Stanford type B AD.

Other authors have, nonetheless, contradicted this, stating that although complete thrombosis of the false lumen may be a sign of scarring of the aortic wall after stent grafting, in most cases, the thrombosis is incomplete or focal and may induce ischemia and/or severe hypertension.9 In addition, partial thrombosis of the false lumen proved to be a significant independent predictor of mortality after discharge.10 Nevertheless, there are no evidence-based recommendations, although strategies including heparinization followed by oral anticoagulation have been described.9

In the authors’ opinion, the way anticoagulation is managed in an initial phase should include the use of rapid reversal parenteral anticoagulants, such as UFH, due to the possibility of severe bleeding and need for emergent surgery. In a subsequent phase, when considering long-term oral anticoagulation, vitamin K antagonists are a safer choice due to their relatively rapid reversal and support with blood products. However, when considering novel oral anticoagulants, the use of antidotes that reverse their effects almost immediately must also be taken into account.

There is no guidance on follow-up imaging for these patients. The authors recommend that in the case of an uncomplicated Stanford type B AD diagnosis, in which anticoagulant therapy is required due to another concomitant disease, a CTA should be performed in the first 24 hours, before hospital discharge and every three months for the first year, or whenever the patient's clinical status changes or laboratory analyses are suggestive of acute bleeding or progression of the dissection. From then onwards, follow-up imaging should be performed annually.

ConclusionThe subject of anticoagulation in AD is rarely addressed in medical literature. However, several cases have been described, in which – either due to the concomitant existence of diseases requiring anticoagulants or the onset of these diseases during hospitalization – anticoagulation treatment is initiated. The authors recommend initially that anticoagulation is achieved with rapid reversal agents and subsequently, in the long-term, that vitamin K antagonists are considered primarily. However, the antidotes recently made available for some novel oral anticoagulants mean that we can begin to consider their use in extreme cases like the one we have presented.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Roque D, Magno P, Ministro A, Santos M, Sousa M, Augusto J, et al. Tromboembolismo pulmonar e disseção da aorta concomitantes: abordagem à anticoagulação. Rev Port Cardiol. 2020;39:351.