Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) is an unusual disease that presents as systemic vasculitis and peripheral eosinophilia in patients with an atopic constitution. Cardiac involvement is unusual and often not prominent on initial presentation, but is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with CSS. We report the case of a young woman with severe acute myocarditis. Coronary arteriography demonstrated extensive focal vasculopathy, consistent with coronary vasculitis, and myocardial biopsy showed eosinophilic myocarditis. This presentation led to an initial diagnosis of CSS in this patient and appropriate therapy resulted in a spectacular remission of disease activity.

A Síndrome de Churg-Strauss é uma doença rara que se caracteriza por vasculite sistémica associada a eosinofilia periférica, tipicamente em doentes com constituição atópica. O envolvimento cardíaco é incomum e geralmente discreto na apresentação inicial mas constitui uma importante causa de morbilidade e mortalidade nestes doentes. Descrevemos o caso de uma mulher jovem admitida por miocardite aguda. A angiografia coronária mostrou lesões coronárias difusas sugestivas de vasculite coronária e a biópsia miocárdica mostrou a presença de miocardite eosinofílica. Esta apresentação clínica permitiu o diagnóstico inaugural de síndrome de Churg-Strauss nesta doente e a instituição de terapêutica adequada resultou na remissão completa da atividade da doença.

Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) is a rare primary systemic vasculitis characterized by peripheral eosinophilia in patients with an atopic condition, typically with a previous history of asthma or allergy.1 It affects both small and medium-sized blood vessels of nearly all organ systems. The pathophysiology of this syndrome can be divided into three stages: first, a prodromal stage characterized by asthma and allergic manifestations; second, eosinophilic infiltration into tissues, predominantly the lungs and myocardium; and finally, a systemic stage, associated with the development of necrotizing vasculitis.2,3 Although cardiac involvement is unusual and often not prominent on initial presentation, subclinical myocardial abnormalities are frequent and are found in more than 50% of post-mortem examinations.1 Symptomatic cardiomyopathy carries a poor prognosis, accounting for about 50% of deaths, and is thus the major cause of mortality in CSS.2 It can present with eosinophilic vasculitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, pericardial effusion, fibrosis, valvular heart disease, conduction disorders, intracavitary thrombi, and cardiomyopathy.4–6 Death is usually due to myocardial infarction, heart failure, malignant ventricular arrhythmias, and/or cardiac tamponade.4

We describe the case of a patient with newly diagnosed CCS presenting with pronounced eosinophilic myocarditis and extensive focal vasculopathy on coronary angiography consistent with vasculitis. After appropriate and timely pharmacologic therapeutic intervention the symptoms resolved completely, as did the coronary lesions and myocardial infiltrates.

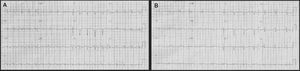

Case reportA 22-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis, asthma and repeated upper respiratory tract infections in the previous two years developed progressive asthenia, dizziness and left leg paresthesias. One month after the beginning of these non-specific symptoms she was hospitalized because of pleuritic chest pain. She had had no recent flu-like symptoms, either of the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract, or other symptoms suggestive of a previous infectious disease. Physical examination was unremarkable; the electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed poor anteroseptal R-wave progression and diffuse T-wave inversion (Figure 1A). Laboratory tests showed eosinophilia (3.83×109/l), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (43 mm/h) and elevated biochemical markers of myocardial injury (peak troponin I 155.6 ng/ml). Serologic and PCR tests were negative for cardiotropic viruses, Aspergillus, Toxoplasma, Chlamydia psittaci and Mycoplasma pneumonia. Specific study for parasites was also negative.

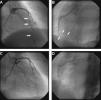

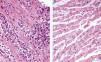

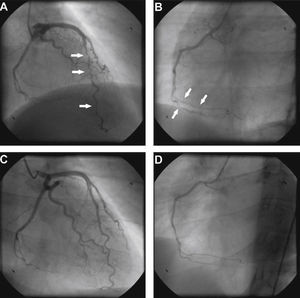

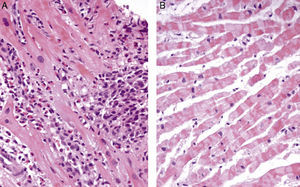

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a small pericardial effusion with no other abnormalities. A diagnosis of myopericarditis was assumed and anti-inflammatory therapy with ibuprofen was initiated. However, the patient's recurrent chest pain persisted, associated with dynamic ECG abnormalities (transient ST-segment elevation in inferior leads) (Figure 1B) and new wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography (inferior wall hypokinesia). Given the unfavorable clinical evolution associated with a significant rise in plasma troponin I concentration and new ECG and echocardiographic abnormalities, despite anti-inflammatory therapy, cardiac catheterization was performed on the fourth day after admission. Coronary arteriography demonstrated irregularity of the larger arteries with long diffuse stenotic lesions in the left anterior descending and right coronary arteries (Figure 2A and B, arrowed), consistent with diffuse vasculitis. A myocardial biopsy showed eosinophilic myocarditis (Figure 3A) and a concomitant nasal biopsy revealed eosinophilic necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis. Immunologic study, including ANCA antibodies, was negative, while electromyography revealed left saphenous nerve mononeuropathy.

Coronary angiography at presentation showing diffuse vessel wall irregularities in the left anterior descending artery (A) and right coronary artery (B). Coronary angiography after one year of immunosuppressive therapy showing resolution of vasculopathy in the anterior descending artery (C) and right coronary artery (D).

Churg–Strauss syndrome was then diagnosed as four out of six criteria were present in this patient: (1) asthma; (2) eosinophilia; (3) mononeuropathy; (4) extravascular eosinophils.7 Pulse intravenous (i.v.) corticosteroid treatment (methylprednisolone 1 g i.v. daily for three days) was started, just after the biopsy results, followed by oral glucocorticoid therapy (prednisone 1.5 mg/kg daily) associated with cyclophosphamide (0.6 g/m2 intravenously once a month). On day one of treatment, the patient's symptoms improved significantly and levels of blood eosinophils fell to 0.02×109/l. Echocardiography performed after 18 days of treatment showed resolution of the pericardial effusion as well as of the left ventricular wall motion abnormalities. Control coronary angiography one year after initiation of therapy showed complete regression of coronary stenotic lesions (Figure 2C and D) and a myocardial biopsy confirmed resolution of eosinophilic myocarditis (Figure 3B). The patient was stable and symptom-free at one year of follow-up under chronic therapy.

DiscussionWe describe the case of a patient with newly diagnosed CSS presenting with extensive myocarditis, which is an unusual clinical manifestation of this disease. According to the American College of Rheumatology, the presence of four or more of the six possible criteria – (1) asthma; (2) eosinophilia (>10% of leukocytes by differential cell count); (3) mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy; (4) migratory or transient pulmonary infiltrates; (5) paranasal sinus abnormality; and (6) extravascular eosinophils – establishes the diagnosis with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99%.7 In our case, a diagnosis of CSS was established based on the patient's history of asthma, hypereosinophilia, mononeuropathy and extravascular eosinophils on myocardial and nasal biopsy.

This case report highlights the possibility of cardiac involvement in patients with CSS and calls attention to this differential diagnosis in the evaluation of myocarditis. This diagnosis is mostly overlooked because major cardiac problems are rarely the presenting manifestations of vasculitis. Involvement of the heart has been described in the third stage of the disease, as observed in our patient. It is usually associated with vasculitic lesions in the myocardium and coronary vessels causing (peri)myocarditis, heart failure, cardiac tamponade, myocardial infarction, or pericardial effusion.8–11 Our patient presented with pronounced myocarditis but pericardial effusion and coronary vasculitis were also evident. The myocardial damage is caused by vasculitis leading to coronary arteritis and coronary occlusion, through the release by activated eosinophils of toxic mediators causing direct myocardial damage,12 or by replacement of the myocardium with granulomas and scar tissue.13,14 Patients with cardiac involvement are mainly ANCA-negative, as in this case.15

In general, the prognosis of CSS is good, with an overall 10-year survival of 81-92%.11,16 However, cardiac involvement is one of the most important predictors of an adverse outcome, causing up to 50% of CSS-related mortality.10,16 In a study on 96 patients,16 78-month survival was 90% in the absence of symptomatic cardiac manifestations, compared to 30% in their presence. Of the patients with myocardial involvement, 39% died in the acute stage of the disease.16 Early diagnosis of cardiac involvement and subsequent adjuvant therapy may prevent progression of cardiac disease and improve prognosis in these patients. Patients with acute multiorgan disease should receive intravenous glucocorticoid (eg. methylprednisolone 1 g daily for three days) followed by oral glucocorticoid therapy.2,17 Prednisone doses of 0.5-1.5 mg/kg per day are typically administered until disease remission is attained and then gradually tapered to the lowest dose required for control of symptoms and signs of active CSS. The higher dose is used for patients with more aggressive disease, including those with cardiac involvement. Clinical remission of isolated pericarditis, without other visceral involvement, can be obtained with corticosteroid therapy alone.13 However, in the case of myocardial involvement the addition of immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. In higher-risk patients, including those with myocardial injury, lower mortality was noted among those who were treated with cyclophosphamide compared to a separate group in which only some patients received cyclophosphamide (7% vs. 26% mortality, respectively).18 Cyclophosphamide may be administered orally every day or intravenously once a month, but insufficient data are available on CSS to make a clear recommendation regarding this choice. There is also disagreement concerning the duration of immunosuppressive therapy. However, in a preliminary study of patients with CSS, those receiving six pulses of cyclophosphamide had more relapses than those receiving 12 pulses (94% vs. 41%).19 Further data are needed to clarify whether the benefits of 12 pulses outweigh the additional risks, especially of bladder toxicity. Our case report clearly demonstrates the possibility of complete reversal of cardiac disease with appropriate steroid and immunosuppressive therapy, which is in agreement with previous studies.19–22 However, this vasculitis can be fulminant if not identified early and may on occasion present with cardiogenic shock with a malignant course requiring urgent transplantation, despite therapy.23,24 Reports of heart transplantation in this setting are rare and only limited information is available on feasibility, outcome or relapse after heart transplantation in patients with CSS. While one case reported a good long-term result,23 recurrent disease after initially successful transplantation was observed in another patient.25 Cardiac involvement in CSS thus requires immediate therapy, which may allow recovery of cardiac function and reduce the significant cardiac mortality associated with CSS, underlining the need for an aggressive invasive diagnostic approach in CSS patients with heart lesions.

Recent research with multimodality assessment, including ECG analysis, echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, has also shown a high incidence of cardiac involvement (62–90%) in patients with full clinical remission, characterized not only by fibrosis, but also by an active inflammatory process.26,27 Since cardiac involvement is one of the most important predictors of an adverse outcome,18 these findings could influence current recommendations for cardiac evaluation and therapeutic decisions in asymptomatic patients. An early diagnosis detecting silent inflammation could be valuable,28 since appropriate therapy can prevent progression to harmful episodes of cardiac disease and so reduce the high mortality associated with these manifestations. Systematic cardiac evaluation in asymptomatic patients with detailed imaging still lacks validation of its clinical benefit but could be an important procedure in the future.

ConclusionBecause of its multiple forms of presentation and multiorgan involvement, diagnosis of CSS can be difficult. As reported here, it may present with severe cardiac disease. Cardiac involvement is a poor prognostic factor, and is a leading cause of mortality in CSS. As shown by this case report, appropriate and aggressive glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide therapy may lead to complete recovery from potentially fatal cardiac disease. Physicians should thus be alert to the possibility of CSS as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with myocarditis, whenever the clinical setting is appropriate. Prompt diagnosis and therapy can change the poor prognosis associated with cardiac involvement in CSS.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Correia AS, Gonçalves A, Araújo V, Almeida e Silva J, Pereira JM, Rodrigues Pereira P, et al. Síndrome de Churg Strauss complicada com miocardite eosinofílica: um desafio diagnóstico 2012. http://dx.doi.org/.