In recent years, the number of patients requiring acute cardiac care has increased, with progressively more complex cardiovascular conditions, often complicated by acute or chronic non-cardiovascular comorbidities, which affects the management and prognosis of these patients. Coronary care units have evolved into cardiac intensive care units, which provide highly specialized health care for the critical heart patient. In view of the limited human and technical resources in this area, we consider that there is an urgent need for an in-depth analysis of the organizational model for acute cardiac care, including the definition of the level of care, the composition and training of the team, and the creation of referral networks. It is also crucial to establish protocols and to adopt safe clinical practices to improve levels of quality and safety in the treatment of patients. Considering that acute cardiac care involves conditions with very different severity and prognosis, it is essential to define the level of care to be provided for each type of acute cardiovascular condition in terms of the team, available techniques and infrastructure. This will lead to improvements in the quality of care and patient prognosis, and will also enable more efficient allocation of resources.

Nos últimos anos, temos assistido a um aumento do número de doentes com necessidade de cuidados cardíacos agudos, com patologia cardiovascular progressivamente mais complexa, muitas vezes complicada por comorbilidades não cardiovasculares agudas ou crónicas, com impacto na abordagem e prognóstico destes doentes. As unidades coronárias têm evoluído para unidades de cuidados intensivos cardíacos, caracterizadas por cuidados de saúde altamente especializados ao doente cardíaco crítico. Tendo em conta que os recursos humanos e técnicos nesta área são limitados, considerámos ser urgente uma reflexão profunda sobre o modelo de organização dos cuidados ao doente cardíaco agudo, incluindo a definição do nível de cuidados, a constituição e formação da equipa e a criação de redes de referenciação.

Paralelamente, é fundamental um investimento claro dos serviços nesta área central da cardiologia, de forma a alavancar o desenvolvimento contínuo e sustentado de outras áreas cardiológicas essenciais, nomeadamente a eletrofisiologia e a cardiologia de intervenção, assegurando cuidados de excelência e de elevada diferenciação a todos os doentes cardíacos críticos.

In recent years there have been significant changes in the cardiac population, in part due to aging, but mainly due to improvements in health care that alter the natural history of cardiovascular disease.

These changes have led to an increase in the number of patients requiring acute cardiac care, with progressively more complex cardiovascular conditions, often complicated by acute or chronic non-cardiovascular comorbidities, which affects the management and prognosis of these patients.

As a result, traditional coronary care units, which played a central role in treating and improving outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction, have evolved into cardiac intensive care units (CICUs), which are able to provide acute cardiac care to patients with a wide range of heart diseases.1

Various authors have analyzed changes in the profile of patients admitted to the CICU, who are now older, with more severe cardiovascular disease and with more comorbidities, especially renal and respiratory failure and sepsis. Hospitalization times are longer and mortality is higher.2–6

The main diagnoses on admission to the modern CICU are complicated and uncomplicated acute coronary syndrome, acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, severe valve disease (especially acute endocarditis), severe arrhythmias, cardiac device dysfunction and infection, complications of interventional cardiology (coronary and structural), high- and intermediate-risk acute pulmonary embolism, post-cardiac arrest states, severe pulmonary hypertension, and grown-up congenital heart disease.4,5

Contemporary management of the critical cardiac patient requires highly specialized health care provided in dedicated CICUs by teams trained and experienced in two different areas of medicine, cardiology and intensive care.

In view of the limited human and technical resources in this area, there is an urgent need for an in-depth analysis of the organizational model for acute cardiac care, including the definition of level of care and the composition and training of the team.

This need was the subject of a recent meeting of the Working Group on Cardiac Intensive Care (GECIC) of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology, at which a full, wide-ranging and productive discussion gave rise to the present consensus document, which is sponsored and endorsed by GECIC.

Organizational model for acute coronary careA modern CICU constitutes the acme of cardiological care, taking in the most complex patients from emergency departments, the coronary fast-track system, catheterization and electrophysiological laboratories, operating rooms and hospital wards.

Acute cardiac care covers patients with conditions of very different severity and prognosis, ranging from acute events that are easily stabilized and treated with relatively low levels of care, to critical patients with complex conditions that require highly specialized care.7 It is thus essential to define the level of care for every cardiovascular condition in terms of the team, available techniques and infrastructure, in order to improve the quality of care and patient prognosis, as well as to enable more efficient allocation of resources.

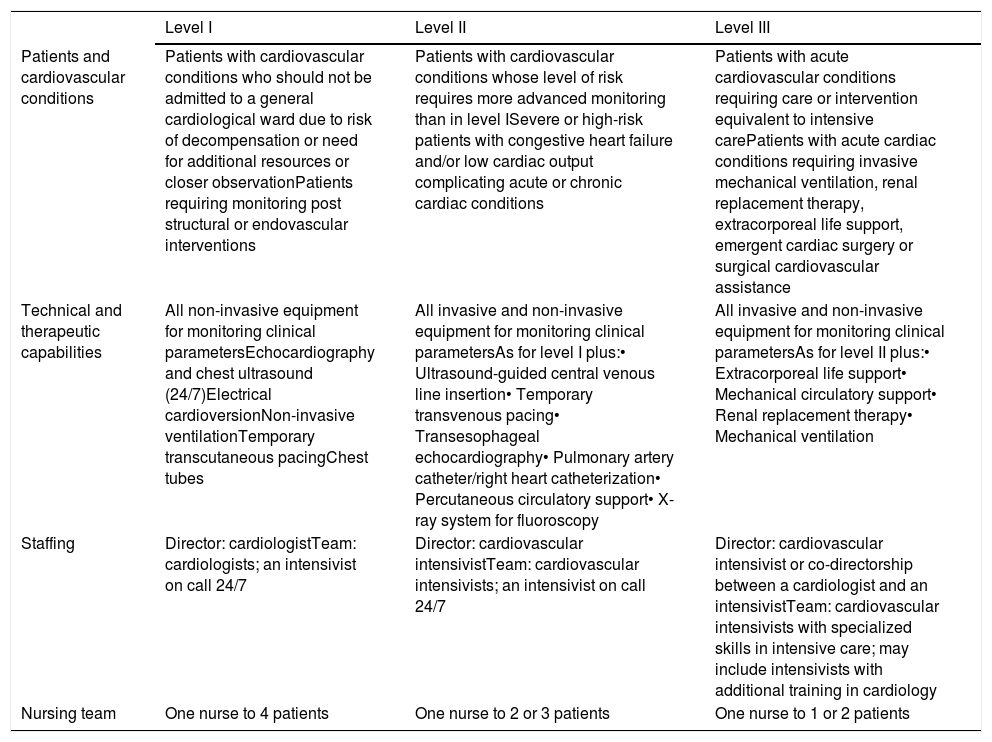

Levels of cardiac intensive care unitsIn order to match the different types of care offered to the different acute cardiovascular conditions that are admitted to intensive care, the Acute Cardiac Care Association (ACCA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed a system for classifying CICUs based on the cardiovascular conditions of patients admitted and the technical and human resources that need to be available at each level.8

In this system, CICUs are categorized in three levels – I, II or III (3, 2 or 1 according to the American Heart Association) – from least to most technical specialization and clinical severity of patients, based on the characteristics of each center and the resources it has available.8,9

According to the ACCU classification, a level III CICU is a hospital unit that is dedicated to the treatment of acute cardiovascular disease and is able to manage all cardiac patients who require monitoring and support of failing vital functions in order to implement prompt diagnostic and therapeutic measures. It has teams specializing in cardiac intensive care and focuses strongly on the safety of the care provided. A level III CICU must be able to provide overall care that is appropriate for the critical cardiac patient, including advanced cardiovascular support for cases of cardiogenic shock, invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, mechanical circulatory assist devices (percutaneous or surgical), and extracorporeal life support.8 Level III units should be associated with lower level units to enable step-down of care.

Table 1 summarizes some of the characteristics of each level of CICU, in accordance with the ACCA's position paper.8

Characteristics of level I, II and III cardiac intensive care units (adapted from Bonnefoy-Cudraz et al.8).

| Level I | Level II | Level III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients and cardiovascular conditions | Patients with cardiovascular conditions who should not be admitted to a general cardiological ward due to risk of decompensation or need for additional resources or closer observationPatients requiring monitoring post structural or endovascular interventions | Patients with cardiovascular conditions whose level of risk requires more advanced monitoring than in level ISevere or high-risk patients with congestive heart failure and/or low cardiac output complicating acute or chronic cardiac conditions | Patients with acute cardiovascular conditions requiring care or intervention equivalent to intensive carePatients with acute cardiac conditions requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, extracorporeal life support, emergent cardiac surgery or surgical cardiovascular assistance |

| Technical and therapeutic capabilities | All non-invasive equipment for monitoring clinical parametersEchocardiography and chest ultrasound (24/7)Electrical cardioversionNon-invasive ventilationTemporary transcutaneous pacingChest tubes | All invasive and non-invasive equipment for monitoring clinical parametersAs for level I plus:• Ultrasound-guided central venous line insertion• Temporary transvenous pacing• Transesophageal echocardiography• Pulmonary artery catheter/right heart catheterization• Percutaneous circulatory support• X-ray system for fluoroscopy | All invasive and non-invasive equipment for monitoring clinical parametersAs for level II plus:• Extracorporeal life support• Mechanical circulatory support• Renal replacement therapy• Mechanical ventilation |

| Staffing | Director: cardiologistTeam: cardiologists; an intensivist on call 24/7 | Director: cardiovascular intensivistTeam: cardiovascular intensivists; an intensivist on call 24/7 | Director: cardiovascular intensivist or co-directorship between a cardiologist and an intensivistTeam: cardiovascular intensivists with specialized skills in intensive care; may include intensivists with additional training in cardiology |

| Nursing team | One nurse to 4 patients | One nurse to 2 or 3 patients | One nurse to 1 or 2 patients |

In Portugal, there is an urgent need to classify CICUs as level I, II or III, in order to optimize patient allocation according to severity of cardiovascular disease and the intensity of care required. To this end, a survey of the characteristics of national centers is essential to improve knowledge of the situation in the country and to identify where and how to provide the best care for every patient.

Composition and training of cardiac intensive care unit teamsThe complexity of advanced cardiac disease, the increased frequency of serious systemic complications, the rapid emergence of new technologies, the crucial role of experience and knowledge in reducing iatrogenic complications, and the overall complexity of working in a modern CICU, all make it essential for the unit to have a dedicated medical team of cardiologists with experience and training in intensive cardiac care available 24/7. It is unacceptable, especially in more specialized CICUs, for physicians to work there for a number of hours on a shift basis without appropriate training to deal with the complexities of cardiac care.

Several studies have demonstrated the advantages of having an intensivist present at all times in intensive care units. The benefits include lower mortality, length of stay and number of events, less need for interventions, and improved clinical outcomes.10–12

Integrated multidisciplinary care, in which activities are coordinated between physicians, nurses (who play a central role in intensive care), respiratory and cardiac therapists, pharmacists, nutritionists and dietitians, psychologists and social workers, is essential if the patient is to be managed comprehensively, effectively and safely.13 Whenever appropriate, physicians from other subspecialties of cardiology should be invited to take part in the discussions and decisions of the heart team, as well as those from other areas of medicine such as cardiac and vascular surgery, intensive care medicine, nephrology and neurology.

In addition, technical advances in interventional cardiology, particularly high-risk angioplasty and percutaneous valve interventions in the catheterization laboratory and ablation of atrial fibrillation and complex tachyarrhythmias and pacemaker lead extraction in the pacing and electrophysiology laboratory, also benefit from the support of the CICU team. In such cases, cardiac intensivists should be kept informed and included in the decision-making and planning of these procedures; whenever this will improve patient safety, they should also be present in the laboratory to prevent and, if necessary, to promptly treat any complications.

It is thus essential to design, equip and organize CICUs to be self-sufficient in the diagnosis and treatment of all patients with cardiovascular disease. It is also crucial that physicians in the CICU should be trained and skilled both in specialized cardiac interventions and in intensive care medicine, as shown by a recently published survey of dual-certified critical care cardiologists in the US, which confirmed the value of specific training in cardiac intensive care beyond the standard training in cardiology, in view of the complexity of the cardiac patients being managed, the techniques that need to be mastered, and the specialized management of the CICU.14

The ACCA has published a model for training in cardiac intensive care, the ACCA Core Curriculum.15 This document provides a standardized curriculum (as opposed to minimum requirements) for training in acute cardiovascular care throughout Europe, bearing in mind the different characteristics of individual institutions. It describes the skills required for the subspecialty of acute cardiac care, including the need to acquire knowledge and experience simultaneously of both general cardiology and general intensive care, as well as the other cardiological and non-cardiological subspecialties, in order to ensure that patients are appropriately referred for more advanced investigations and therapies. In parallel with the three levels of care the ACCA defines for the CICU,8 their Core Curriculum sets out three levels of competence for those working in such a unit, with increasing requirements in terms of knowledge, competence in performing techniques or procedures, and autonomy.15

Acute cardiac intensive care is an emerging subspecialty within cardiology that, like any subspecialty, requires training, formal assessment and continuing education in order to acquire specific skills. However, compared to the current needs, there is a significant shortage of specialists with the combination of knowledge and competences required to work in the highly specialized CICU environment.7,16,17

Those working in the CICU, particularly physicians and nurses, should have relevant experience in cardiac intensive care, preferably gained in internationally recognized reference centers and regularly updated by national or international certification processes, in order to ensure the quality of care provided.

Specialization in intensive care in Portugal can currently be achieved by two pathways: a 60-month medical residency, or a fellowship in intensive medicine (the ‘classic’ pathway of a base specialty plus 27-38 months of intensive medicine). Given these two possibilities, the question arises as to which is the better model for the subspecialty of cardiac intensive care: fellowship in general intensive care after completing a specialization in cardiology, or the establishment of a subspecialty in cardiac intensive care based on the training model proposed by the ACCA.

In our opinion, the latter option is the better one. There is thus an urgent need to develop and approve a formal training plan on the basis of which to advance to the formalization of the subspecialty of cardiac intensive care in Portugal. We are aware of the difficulties and challenges that this option presents, but we consider that such a course should be regarded as a priority for cardiology in this country.

Implementation of protocols, assessment of results and continuing improvementSafety is of paramount importance in the cardiac intensive care setting. Critical patients with complex cardiovascular disease are at high risk of developing major systemic complications, some of them related to intensive care procedures themselves, including renal and respiratory failure, thrombosis and bleeding, catheter-related infections, ventilator-acquired pneumonia, sepsis, and multiorgan dysfunction.9

It is crucial to establish protocols and to adopt safe clinical practices to improve levels of quality and safety in the treatment of critical cardiac patients.9,13,18 Such protocols should be put in place for ultrasound-guided central venous line insertion, non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring based on echocardiographic parameters, prevention of nosocomial infection, protective mechanical ventilation, prevention of contrast nephropathy and venous thromboembolism, sedation and analgesia, and other situations.

When protocols and guidelines have been implemented, evaluation of quality indicators in the CICU is essential to identify areas that require further development and to encourage personnel to improve their performance. To this end, audit programs should be put in place that include assessment of adherence to established protocols and guidelines and of pre-existing quality indicators such as readmission rates, length of stay, mortality and morbidity, and rates of nosocomial infection.9,13 Quality appraisal should follow national criteria as set out by medical societies. As this is likely to be complex and time-consuming to implement, the establishment of local systems may be a way to speed up the process.

In addition, the creation of local registries and databases, as well as participation in national and international registries, will provide valuable sources of information for controlling the quality of care and for developing clinical research.13 CICUs are a prime area for many types of research, including multicenter studies, given the sophistication of their equipment and instrumentation, the high incidence of cardiovascular events that occur in them, and the close physician-patient relationships that develop there.

Referral networksThe complexity of cardiac disease and the vulnerability of critical cardiac patients to multiorgan dysfunction mean that managing these patients requires rapid decisions with narrow safety margins, dynamic risk stratification, and prevention and prompt recognition of complications. At the same time, advanced technology is also crucial to this task, particularly cardiac imaging methods, interventional cardiology techniques and ventricular assist devices, as well as sophisticated modes of mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapies. As explained above, it is essential that those responsible for critical cardiac care should have training and experience in specialized cardiological interventions and competence in intensive care medicine. A multidisciplinary approach and consultations with specialists in related areas of medicine are at the core of the heart team.

In view of the limited human and logistical resources available to health systems and the better results obtained in high-volume CICUs, it is important to establish regional referral networks that include a range of organizational models with different levels of human and technological resources.8 This will help provide every patient with the level of care that is most appropriate for their clinical situation. A good example of the importance of this organized hierarchy of care is that of patients who require advanced circulatory support, particularly extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

It is thus recommended that the most complex patients be transferred from a level I or II CICU, a cardiology ward, or even directly before hospital admission, to a level III unit, instead of being admitted to a general intensive care unit, which is what currently happens in most cases.

For this purpose, formalized referral networks should be set up that link hospitals and CICUs of different levels, with clearly defined referral protocols that include clinical criteria and transfer modalities, treatment protocols before and during transport, on-time information on bed availability, and reliable communication channels between all parties involved.8,19

ConclusionsThe present time poses significant challenges in this exciting area of cardiology that call for an urgent in-depth examination of the best path to follow.

The contemporary CICU cardiologist needs to establish relationships with prehospital networks, strengthen collaboration between units, and maintain communication with other areas of cardiology and other medical and surgical specialties, focusing on continuing education, training of residents and newly qualified subspecialists, and controlling the quality of care provided to patients.

Since the severity and prognosis of patients in acute cardiac care vary considerably, the level of care to be provided must be defined for each acute cardiovascular condition in terms of the team, techniques and infrastructure, in order to improve the quality of care and the patient's prognosis, and also to enable more efficient allocation of resources.

Clear definition of organizational models for CICUs, including close collaboration between cardiology and intensive medicine, the establishment of national referral networks linking hospitals with units with different levels of specialization, cooperation between centers, and training and acquisition of competences, are all essential elements to improve care for acute cardiac patients.

At the same time, investment is needed in services in this important area of cardiology in order to leverage the continuing and sustained development of other essential areas of cardiology including electrophysiology and interventional cardiology, to provide excellence of care and a high degree of specialization for all critical cardiac patients.

The time for change is now.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

GECIC thanks all the experts who contributed to the discussions and writing of this document.

Please cite this article as: Monteiro S, Timóteo AT, Caeiro D, Silva M, Tralhão A, Guerreiro C, et al. Cuidados intensivos cardíacos em Portugal: projetar a mudança. Rev Port Cardiol. 2020;39:401–406.