In patients admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the presence of anemia is a predictor of prognosis. However, risk scores used for prognostic stratification do not include this variable.

ObjectivesTo evaluate whether the presence of anemia on admission in patients with ACS has additional value over the GRACE risk score in the prediction of short- and medium-term mortality.

MethodsBetween January 2005 and December 2008, we assessed consecutive patients admitted to our intensive care unit for ACS and included in our single-center ACS registry. In all patients information was collected on demographic and anthropometric variables, risk factors for coronary artery disease, and clinical and laboratorial data on admission, including hemoglobin. Patients with anemia were identified (hemoglobin <12g/dl for women and <13g/dl for men). Patients were classified as low, intermediate or high risk on the GRACE risk score (<126, 126–154 and >154, respectively). In-hospital, 30-day and one-year mortality were analyzed.

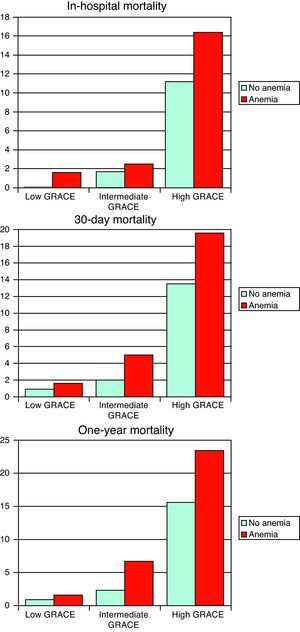

ResultsThe study population included 1423 patients with a mean age of 64±13 years, 69% male, anemia on admission being present in 27.7%. These patients were older and more often female, with a higher proportion of hypertensives and diabetics, and more often had a history of myocardial infarction, worse Killip class on admission and higher GRACE risk score. On the other hand, fewer were smokers, fewer presented ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and they were less often treated with beta-blockers, statins and coronary angioplasty. They had more bleeding complications during hospital stay. In-hospital (10% vs. 4%), 30-day (12% vs. 5%) and one-year mortality (15% vs. 6%) were higher in the anemia group (p<0.001). In bivariate analysis, the presence of anemia was a predictor of in-hospital (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.57–3.85, p<0.001), 30-day (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.65–3.69, p<0.001) and one-year mortality (OR 2.66, 95% CI 1.83–3.86, p<0.001). However, after adjustment for other variables, this association was no longer significant. When we analyzed the presence or absence of anemia for each GRACE risk score group, there was only a difference in one-year mortality, which was higher in both the intermediate- and high-risk GRACE score groups (6.7% vs. 2.3%, p=0.024; 23.4% vs. 15.6%, p=0.022, respectively), with a trend for higher 30-day mortality in the high-risk group (19.6% vs. 13.5%, p=0.056).

ConclusionsOur data confirm that anemia is an important predictor of short- and medium-term mortality after ACS, but non-significant after adjustment or when included in the GRACE risk score. However, combining this variable with the GRACE risk score can improve risk stratification in high-risk groups, and it should be included in the prognostic evaluation of these patients.

Nos doentes admitidos com síndrome coronária aguda (SCA), a presença de anemia é um fator predizente de prognóstico. Contudo, os diversos scores de risco após SCA não incluem este fator.

ObjetivosAvaliar se a presença de anemia na admissão em doentes com SCA tem valor acrescido relativamente ao score GRACE na predição de mortalidade a curto e médio prazo.

MétodosEntre janeiro 2005 e dezembro 2008, avaliaram-se os doentes admitidos consecutivamente na nossa Unidade de Cuidados Intensivos por SCA e incluídos no registo de SCA do centro. Em todos os doentes foram colhidos dados demográficos, antropométricos, fatores de risco para doença coronária, dados clínicos e laboratoriais da admissão, incluindo hemoglobina. Foram identificados os doentes com anemia (hemoglobina < 12g/dL nas mulheres e < 13g/dL nos homens). Os doentes foram divididos em risco baixo, intermédio e alto: <126, 126-154 e > 154 para o score GRACE, respetivamente. Analisou-se a ocorrência de morte intra-hospitalar, aos 30 dias e ao primeiro ano de seguimento.

ResultadosIncluíram-se 1423 doentes, com idade média de 64 ± 13 anos, 69% do sexo masculino, identificando-se a presença de anemia na admissão em 27,7% dos doentes. Estes doentes eram mais idosos, com predomínio do sexo feminino, mais hipertensos e diabéticos, maior número com história prévia de enfarte, com pior classe de Killip na admissão e score GRACE mais alto. Pelo contrário, eram menos fumadores, com menor apresentação como enfarte com supradesnivelamento ST e receberam menos bloqueadores beta, estatinas e angioplastia coronária. Tiveram também mais complicações hemorrágicas durante o internamento. A mortalidade intra-hospitalar (10 versus 4%), aos 30 dias (12 versus 5%) e ao primeiro ano (15 versus 6%) foram superiores no grupo com anemia (p < 0,001). Na análise bivariada, a presença de anemia é fator predizente de mortalidade intra-hospitalar (OR 2,46, IC 95% 1,57-3,85, p < 0,001), aos 30 dias (OR 2,47, IC 95% 1,65-3,69, p < 0,001) e ao primeiro ano (OR 2,66, IC 95% 1,83-3,86, p < 0,001), não se mantendo, contudo, esta associação após ajuste para outras variáveis. Associando a presença de anemia ao score GRACE, diferencia apenas para a mortalidade ao primeiro ano (com maior mortalidade) os grupos de risco intermédio e alto do score GRACE (6,7 versus 2,3%, p=0,024; 23,4 versus 15,6%, p=0,022, respetivamente), com uma tendência para diferenciar a mortalidade aos 30 dias no grupo de risco alto de score (19,6 versus 13,5%, p=0,056).

ConclusãoOs nossos dados confirmam que a anemia é um fator predizente importante de mortalidade a curto e médio prazo após SCA, contudo, não significativo quando ajustado ou incluído no score GRACE. Contudo, a sua combinação com o score GRACE pode melhorar a estratificação de risco, em particular no alto risco.

The increased risk associated with anemia has been widely reported in various forms of heart disease.1–4 Anemia is common in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), particularly elderly patients, who represent a growing percentage of those admitted for ACS.5,6 Previous studies have demonstrated that anemia is an independent predictor of in-hospital and 30-day mortality.7 There are various risk stratification scores available for ACS, the latest and most widely used being the one based on the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events – the GRACE score – since it more closely reflects reality than previous scores.8 Surprisingly, anemia on admission is not usually included in risk prediction models, including the GRACE score.

We set out to assess the impact of anemia on overall short- and medium-term mortality after ACS, as well as the association between this variable and the GRACE score.

MethodsThe study population consisted of 1423 consecutive patients admitted to our intensive care unit for ACS and included in our single-center ACS registry between January 2005 and December 2008.

We analyzed patients’ demographic characteristics, risk factors for coronary artery disease, previous heart disease, laboratory data on admission, glomerular filtration rate (estimated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula9), in-hospital treatment and major bleeding (defined as life-threatening or requiring transfusion). The need for transfusion was at the attending physician's discretion. Automatic devices were used for hematological measurements. Baseline hemoglobin levels were available for all patients. Anemia was defined according to the World Health Organization criteria (hemoglobin on admission <13g/dl in men and <12g/dl in women).10 Follow-up was by telephone in all surviving patients at 30 days and one year. Overall in-hospital, 30-day and one-year mortality were assessed.

The patients were divided into groups according to the GRACE risk score: low risk (<126, n=407); intermediate risk (126–154, n=462); and high risk (>154, n=554).

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as means±standard deviation and compared using the Student's t test. Those with a non-normal distribution (total and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, admission blood glucose, estimated glomerular filtration rate, peak CK and admission NT-proBNP) were expressed as medians and interquartile range and compared using the Mann–Whitney test; they were then logarithmically transformed in order to improve normality and used in the subsequent statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. The association between the variables and mortality was assessed by logistic regression analysis of all variables potentially linked to mortality. In order to assess whether the inclusion of anemia has additional value over the GRACE score, we compared the fit of the model based on the GRACE score alone and after inclusion of anemia. The c statistic was used to assess the discriminatory power of the model by analysis of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess goodness of fit. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

ResultsBetween January 2005 and December 2008, 1423 patients were admitted to our intensive care unit with a final diagnosis of ACS, and 12-month follow-up was achieved in all survivors. Anemia was present in 394 patients (27.7%). The baseline characteristics of the study population divided according to the presence or absence of anemia are shown in Table 1. Patients with anemia were older, with a higher proportion of women, and had lower body mass index, more often had a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and had more risk factors for coronary artery disease, with the exception of smoking, which was less common. Renal function was similar in the two groups. Anemic patients had lower systolic blood pressure, but worse Killip class and higher GRACE score. The form of presentation in these patients was predominantly ST-elevation MI, but this was less frequent than in the group without anemia. They also less often received treatment in accordance with international guidelines (Table 2). In the total population, intracranial bleeding occurred in two patients, retroperitoneal bleeding in two, gastrointestinal bleeding in 16, genitourinary tract bleeding in six, intrapulmonary bleeding in one, bleeding dyscrasia in one, and puncture site bleeding from invasive procedures in nine (some with associated compartment syndrome); another 23 patients had other bleeding complications. All required transfusion. As expected, major bleeding occurred more frequently in the group with anemia (odds ratio [OR] 4.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.39–6.95, p<0.001). Major bleeding was a predictor of in-hospital (OR 10.59, 95% CI 5.84–19.21, p<0.001), 30-day (OR 8.42, 95% CI 4.73–14.99, p<0.001) and one-year mortality (OR 8.07, 95% CI 4.61–14.16, p<0.001), all of which were significantly higher in anemic patients (Table 3).

Baseline clinical characteristics according to the presence or absence of anemia.

| Anemian=394 | No anemian=1029 | p | |

| Age, years | 69±12 | 62±13 | <0.001 |

| Male, % | 57 | 73 | <0.001 |

| Risk factors, % | |||

| Hypertension | 71 | 64 | 0.005 |

| Dyslipidemia | 48 | 51 | 0.329 |

| Diabetes | 36 | 21 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 21 | 42 | <0.001 |

| Previous history, % | |||

| MI | 21 | 14 | 0.001 |

| PCI | 12 | 11 | 0.504 |

| CABG | 5 | 3 | 0.139 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26±4 | 27±4 | <0.001 |

| Admission | |||

| ST elevation, % | 54 | 62 | 0.003 |

| Killip class≥2, % | 31 | 18 | <0.001 |

| HR, bpm | 80±22 | 78±18 | 0.266 |

| SBP, mmHg | 130±29 | 136±28 | 0.001 |

| Ejection fraction<35%, % | 11 | 8 | 0.138 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 176±94 | 161±78 | 0.005 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 | 73±38 | 73±26 | 0.995 |

| GRACE score | 161±37 | 141±35 | <0.001 |

| Previous medication, % | |||

| Aspirin | 26 | 21 | 0.026 |

| Other antiplatelet | 9 | 5 | 0.002 |

| ACEI | 26 | 19 | 0.006 |

| Beta-blocker | 17 | 14 | 0.178 |

| Statin | 29 | 22 | 0.003 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 3 | 2 | 0.379 |

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR: heart rate; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

In-hospital treatment according to the presence or absence of anemia.

| Anemian=394 | No anemian=1029 | p | |

| Aspirin, % | 96 | 98 | 0.005 |

| Clopidogrel, % | 86 | 94 | <0.001 |

| ACEI, % | 83 | 86 | 0.158 |

| Beta-blocker, % | 74 | 84 | <0.001 |

| Statin, % | 89 | 94 | 0.002 |

| Coronary angioplasty, % | 63 | 77 | <0.001 |

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

Complications and outcomes according to the presence or absence of anemia.

| Anemian=394 | No anemian=1029 | p | |

| Major bleeding, % | 9 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Stroke/TIA, % | 2 | 1 | 0.330 |

| Mechanical complications, % | 10 | 5 | 0.005 |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 10 | 4 | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality, % | 12 | 5 | <0.001 |

| One-year mortality, % | 15 | 6 | <0.001 |

TIA: transient ischemic attack.

In bivariate analysis, anemia increased mortality risk: in-hospital – OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.57–3.85, p<0.001; at 30 days – OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.65–3.69, p<0.001; and at one year – OR 2.66, 95% CI 1.83–3.86, p<0.001. However, after adjustment in multivariate analysis for age, gender, risk factors, admission parameters, treatment and major bleeding, anemia was no longer an independent predictor of mortality for any of the outcomes under analysis (Table 4).

Independent predictors of in-hospital, 30-day and one-year mortality, including anemia and corresponding adjusted odds ratio.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

| In-hospital | |||

| Age | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.005 |

| SBP | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 0.27 | 0.15–0.47 | <0.001 |

| Log blood glucose | 7.50 | 3.57–15.75 | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 4.79 | 2.33–9.66 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 1.00 | 0.57–1.77 | 0.998 |

| 30 days | |||

| Age | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.005 |

| SBP | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 0.35 | 0.21–0.58 | <0.001 |

| Log blood glucose | 4.06 | 2.21–7.46 | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 5.29 | 2.67–10.49 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 1.09 | 0.67–1.79 | 0.731 |

| One year | |||

| Age | 1.07 | 1.04–1.09 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | <0.001 |

| SBP | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | 0.005 |

| Beta-blocker | 0.38 | 0.24–0.61 | <0.001 |

| Log blood glucose | 3.66 | 2.07–6.50 | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 4.91 | 2.12–9.55 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 1.18 | 0.74–1.86 | 0.490 |

Variables included in the model: age, gender, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, smoking, diabetes, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, Killip class, ST elevation, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, beta-blockers, percutaneous coronary intervention, admission blood glucose, major bleeding and anemia. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; and SBP: systolic blood pressure.

On analysis of the impact of anemia on mortality in the three groups classified according to the GRACE risk score, there was a significant difference in one-year mortality only, which was higher in the intermediate- and high-risk groups, with a trend for higher 30-day mortality in the high-risk group (Figure 1).

Including anemia in a predictive model based on the GRACE risk score produced a slight improvement in its discriminatory power, but no improvement in calibration of the model. Thus, the inclusion of anemia provided no additional benefits over the GRACE score in terms of prognostic assessment (Table 5).

Assessment of fit of the risk model based on GRACE score alone and after inclusion of anemia.

| Goodness-of-fit measures | In-hospital mortality | 30-day mortality | One-year mortality | |||

| Without anemia | With anemia | Without anemia | With anemia | Without anemia | With anemia | |

| c statistic | 0.871 | 0.872 | 0.834 | 0.837 | 0.831 | 0.847 |

| Chi-square (H–L) | 11.43 | 10.57 | 4.54 | 9.52 | 2.02 | 3.07 |

| p (H–L) | 0.178 | 0.227 | 0.805 | 0.301 | 0.981 | 0.930 |

H–L: Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic.

The presence of anemia on admission for ACS has been identified as an independent prognostic factor,7 but risk stratification scores have consistently excluded this variable.8 Anemia decreases myocardial oxygen supply, which is already diminished in ACS, thus worsening its presentation and prognosis.11 At the same time, anemia is common at older ages and is frequently associated with other comorbidities that can also affect prognosis and limit the aggressiveness of treatment. It is often associated with major bleeding (as seen in our population) and renal failure. Anemic patients were under-treated, as in other series, with the exception of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors12; they were less often treated with antiplatelet agents, as well as with other drugs with proven benefits on survival following ACS. The risk of contrast nephropathy may also have limited the use of invasive procedures, as demonstrated in other studies.13

Surprisingly, our results did not confirm previous data suggesting anemia as an independent predictor of prognosis after adjustment for other confounding variables. However, there were some differences in our population compared to those of other studies, notably a higher rate of ST-elevation MI, younger age, less severely impaired renal function and greater use of beta-blockers, which may have contributed to the differences in results. Mortality was also lower than previously reported in anemic patients, probably also the result of the above-mentioned differences. A recent study by Meneveau et al. of 1610 patients from a French registry showed that adding anemia to the GRACE score increased its predictive value for short-term mortality, albeit only slightly.14 Maréchaux et al. also showed an association between anemia or hemoglobin decline with the occurrence of events when combined with the GRACE score. However, this study excluded patients who had bleeding events or were transfused during hospitalization, and so their population differed from ours.15

In our population combining anemia with the predictive model of the GRACE score alone provided only slight additional value with regard to in-hospital mortality but no additional predictive value in the medium term, which justifies its exclusion from the GRACE score and probably from earlier scores. We thus consider that including anemia in the GRACE score would not be useful. Nevertheless, we would stress that in intermediate-risk and particularly high-risk patients according to the GRACE score, the presence of anemia identifies a group at even greater risk (almost double) for short- and medium-term mortality, and we therefore recommend its use to provide additional information to that provided by the GRACE score for risk stratification, but not its inclusion in the model itself.

The definition used in our study for major bleeding may be somewhat controversial, since in recent years there has been much debate on the subject, with clinical trials on antithrombotic therapy using different definitions. However, most use the TIMI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) or GUSTO (Global Use of Strategies to Open occluded coronary arteries) classification.16,17 This question is an important one, since some studies have shown significant discrepancies in the recorded incidence of bleeding events in the same clinical trial depending on the definition used. One example is the PURSUIT (Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in Unstable angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy) trial, in which the incidence of major bleeding with eptifibatide was 3.0% according to the TIMI classification and 1.1% according to the GUSTO criteria.18 Moreover, these definitions were developed to classify the bleeding complications of thrombolytic therapy and have been less thoroughly validated in the context of non-ST elevation MI and mechanical reperfusion. For this reason, other classification systems have been proposed. The TIMI score is essentially based on laboratory test results, while the GUSTO classification is basically clinical. Since it was clear that each system identifies bleeding events that are not identified by the other,19 new classifications have been proposed that are a mixture of both types of scale. In addition, previous studies have shown that after adjustment for transfusions or when both scores are included in the model, only the GUSTO classification predicts adverse events, suggesting that assessment of bleeding by clinical criteria is more useful than by laboratory criteria.19 Thus, an ideal system would include the GUSTO clinical scale and the need for transfusion. In 2005, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis proposed a classification system for major bleeding in non-surgical patients, defining it as fatal, symptomatic in a critical area or organ (such as intracranial, intraspinal, retroperitoneal, pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome), or bleeding that causes a drop in hemoglobin of ≥2g/dl or that requires transfusion of ≥2 units of red cell concentrate.20 In 2007, Serebruany and Atar also proposed a new classification of bleeding events known as the BleedScore, in which the most severe are categorized as “alarming”, such as intracranial, life-threatening or requiring transfusion.21 The retrospective nature of the present study, based on information in a database, meant that we had no details on bleeding events such as the number of units transfused. Furthermore, the laboratory data for some patients did not include the minimum hemoglobin value, and so it was not possible to assess any drop in hemoglobin. It was thus decided to use a more clinical classification system that is close to the BleedScore.

Identification of patients with anemia and hence at higher bleeding risk, which is an important predictor of short- and medium-term mortality, should lead to changes in clinical practice that will help reduce bleeding complications, including radial access for percutaneous interventions and use of smaller caliber catheters, greater care in dosage of antithrombotic drugs, closer monitoring of coagulation parameters and prophylactic gastric protection. The presence of anemia may influence the choice of antithrombotic regime and revascularization method, but is not a contraindication to these therapies, only requiring strategies to prevent complications, as mentioned above.

Study limitationsThe results presented were obtained from a single center, and some of the characteristics of the study population differ from those of other centers, and so caution is needed in generalizing the results. Furthermore, although a relatively large number of patients were included, an even larger sample would lend greater weight to the results.

It may be useful to assess any drop in hemoglobin during hospitalization, since this could add important information to the GRACE score.

The mechanisms responsible for the presence of anemia on admission were not analyzed in the present study due to the limitations imposed by the data being obtained from a database.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Timóteo, AT. Pode a presença de anemia na admissão melhorar a capacidade preditiva do score GRACE para mortalidade a curto e médio-prazo após síndrome coronária aguda? doi:10.1016/j.repc.2011.12.015.