We describe the case of a rare complication after transcatheter closure of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). The diagnostic imaging techniques used, included echocardiography and computed tomography angiography (CTA).

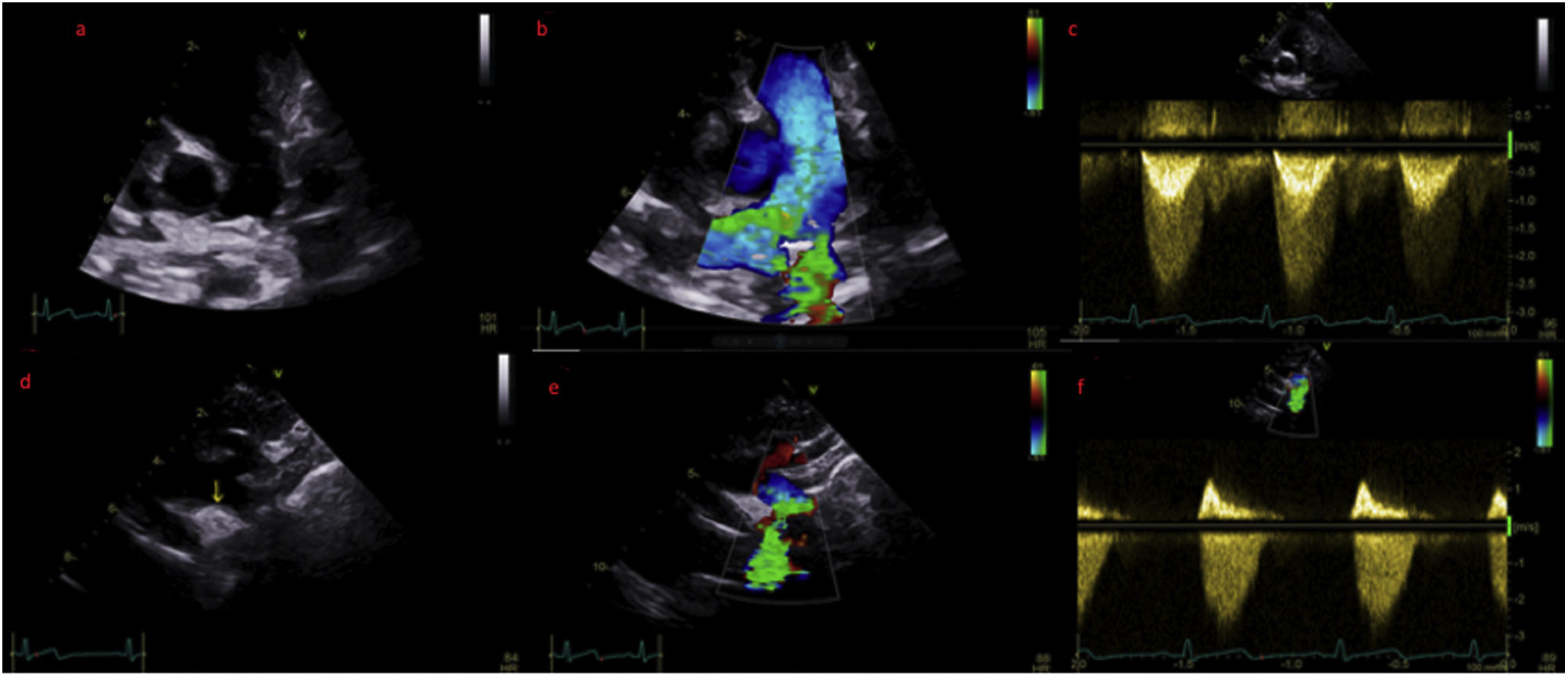

The case concerns a four year old female refugee who was referred to our hospital's Pediatric Cardiology Department by the camp's general doctor, after discovering a systolic murmur on physical examination. The patient's noteworthy medical history consisted of a percutaneous cardiovascular operation while an infant, for which there was no documentation available. On inspection, the patient was alert, non-dyspneic, non-cyanotic with an expected growth and weight for his age. His arterial pressure was 110/75mmHg without radio-radial or radio-femoral pulse delay. On auscultation, there was a 3/6 systolic crescendo/decrescendo murmur in the left precordial area, without a palpable thrill. An echocardiogram was performed, where an echodense structure was noted in the region of the ductus arteriosus (Video 1 and 2), causing moderate stenosis in both left pulmonary artery (Figure 1, panel a–c; Video 3) and descending aorta (Figure 1, panel a–f; Video 4–6) through protrusion.

(a) Modified parasternal short axis view of the main pulmonarty artery (PA) and its bifurcation. (b) Same view with colour doppler, revealing turbulent flow in the left pulmonary artery (LPA). (c) Doppler derived mean pressure gradient across the LPA stenosis was estimated at 20 mmHg. (d) Suprasternal view of the aortic arch where the echodense structure is visualized. (e) Same view with colour doppler aliasing. (f) Doppler derived mean pressure gradient across the descending aorta stenosis was 19 mmHg.

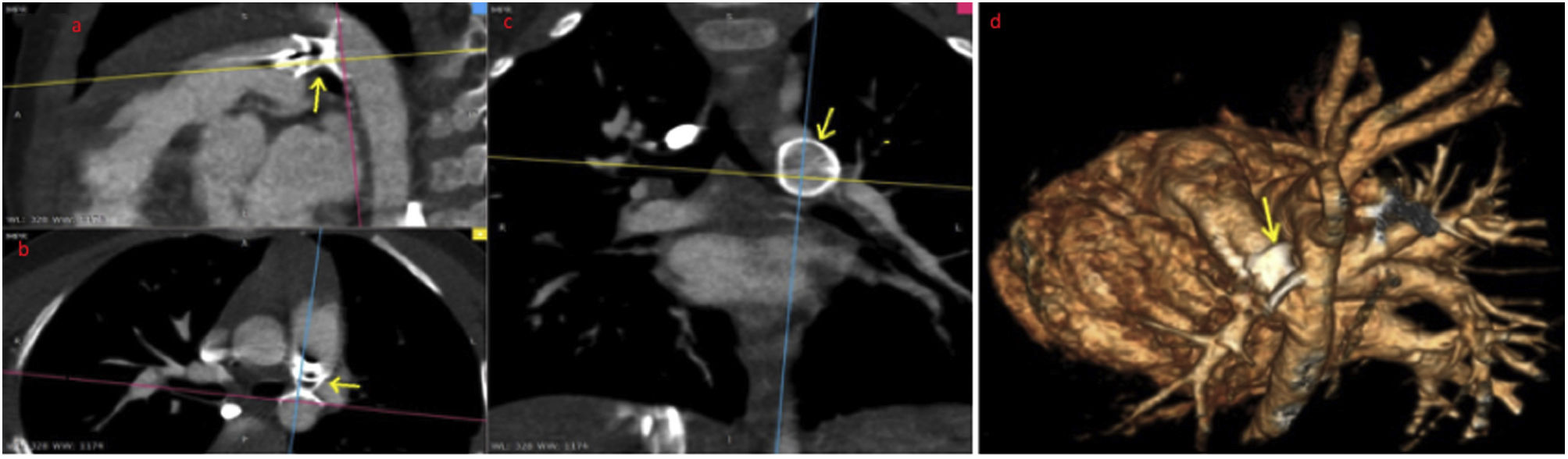

A CTA was then deemed necessary, which demonstrated the presence of an occluder in the aforementioned area, eliciting stenosis in both vessels (Figure 2, Video 7)

The PDA accounts for 5%–10% of all congenital heart defects with the prevalence of hemodynamically significant PDA being 0.5/1000 live births.1 Clinical presentation depends on the diameter and length of the PDA and the associated systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance. PDA may also exist with other cardiac anomalies, which must be considered at the time of diagnosis. The incidence of PDA increases with decreasing gestational age and low birth weight. Spontaneous closure rate of PDA in preterm neonates varies from 35% to 75% in the first year of life. Large PDAs are unlikely to close spontaneously.2 Cassels et al. defined persistence of a PDA when present in infants >3 months. Thus, it is then considered abnormal, and treatment should be contemplated.

Transcatheter closure of PDA is a well-established method of treatment for the majority of pediatric patients. Currently, Amplatzer™ duct occluders are the most widely used for closure of moderate- and large-sized PDAs. The Amplatzer™ duct occluders are approved in children >6 months and weighing >6kg. Although the transcatheter closure of PDA has proven to be effective and safe, several complications, such as embolization, narrowing of the left pulmonary artery, aortic obstruction, hemolysis, and infective endocarditis have been reported. In general though, the complication rate is low.3

Stenosis of both left pulmonary artery and descending aorta after transcatheter closure of a PDA is an extremely rare complication, occurring particularly in low-body weight patients with a large PDA.4 According to the literature, no cases of at least moderate stenosis of both arteries have been reported. Mild solitary stenosis of either the left pulmonary artery or the descending thoracic aorta is not uncommon. However, the stenoses usually resolve within six months of closure and rarely require reoperation.5

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.