Systemic sclerosis (SS) is a chronic disease in which there may be multisystem involvement. It is rare (estimated prevalence: 0.5–2/10000) with high morbidity and mortality, and there is as yet no curative treatment.

We report the case of a young woman newly diagnosed with SS, in whom decompensated heart failure was the main manifestation.

A esclerose sistémica (ES) é uma doença crónica com possível apresentação multi-sistémica. É considerada uma doença rara (prevalência estimada: 0.5-2/10,000) com alta morbilidade e mortalidade para a qual não há cura hoje em dia.

Relatamos o caso de uma jovem mulher, recém diagnosticada de ES por afetação pleural e cutânea, com insuficiência cardíaca global no momento da consulta.

A 38-year-old woman without cardiovascular risk factors, diagnosed with SS one year previously, who had presented with simultaneous involvement of the skin and pleura and was under treatment with steroids and calcium channel blockers, was admitted to the emergency department because of progressive dyspnea at rest accompanied by orthopnea, abdominal distension, and lower limb edema for three weeks.

On physical examination, her blood pressure was 117/81mmHg and heart rate was 111beats/min. The presence of microstomia, sclerodactyly, and diffuse cutaneous involvement were noted. Cardiac auscultation was normal without murmur or rub. Breath sounds were absent at the lung bases on both sides. Jugular venous engorgement at 45° was present, with positive hepatojugular reflux. Other physical signs were tender hepatomegaly with bilateral and symmetrical lower limb edema extending up to the knee joint.

The 12-lead electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, incomplete right bundle branch block with left anterior hemiblock and first-degree atrioventricular block (PR interval 210ms, QRS interval 111ms).

Baseline arterial blood gas analysis showed hypoxemia as the only abnormality.

Blood tests revealed microcytic anemia (hemoglobin 9.9g/dl, mean corpuscular volume 69.0fl) and slight abnormalities in coagulation parameters (INR 1.5) without renal dysfunction.

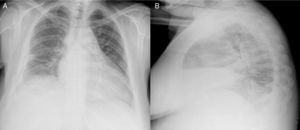

The chest X-ray showed findings consistent with pleural effusion, mainly at the right base (Figure 1).

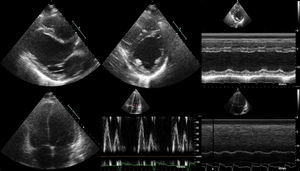

Transthoracic echocardiography showed mild left ventricular (LV) dilation (end-diastolic diameter [EDD] 55mm, end-systolic diameter 49mm), normal LV thickness, asynchronous LV wall motion, LV ejection fraction 37% by the Teichholz method, LV diastolic dysfunction (restrictive pattern), right ventricular (RV) dilation (EDD 48mm in 4-chamber apical view) and impaired RV systolic function (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion 9mm), without evidence of significant pulmonary hypertension (Figure 2).

During her hospital stay the patient received conventional heart failure therapy, with a favorable response. Pro-BNP levels were found to be high (8191.0pg/ml).

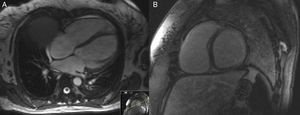

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a slightly dilated LV with severe LV systolic dysfunction (LV ejection fraction 21%), together with anterolateral subendocardial delayed enhancement, possibly due to fibrosis, and slight RV dilatation (EDD 50mm) with severe systolic dysfunction (Figure 3).

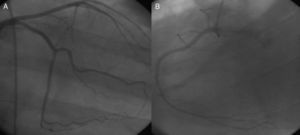

Diagnostic workup was completed with cardiac catheterization, which showed no significant coronary artery stenosis or signs of significant pulmonary hypertension (peak pulmonary artery systolic pressure 30mmHg, mean 17mmHg, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 15mmHg) (Figure 4).

The patient was eventually discharged, clinically stable, with a diagnosis of congestive heart failure and biventricular systolic dysfunction in the context of cardiomyopathy, possibly related to SS. This diagnosis was made on the basis of the absence of other potential causes (coronary disease, hypertension, or family history of heart disease), since a definitive diagnosis based on histological criteria was not available.

Diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were added to her routine SS treatment.

DiscussionSS, also called systemic scleroderma, is a chronic disease in which there may be multisystem manifestations, as can be seen in the case presented. There is still debate concerning the role of myocardial fibrosis as a causative mechanism of heart failure. Current hypotheses include arteriolar endothelial injury resulting in fibrosis and vessel obliteration. One theory is that necrotic cardiomyocytes induce recruitment of fibroblasts and their differentiation into myofibroblasts. According to another theory, evolution of the disease with permanent arteriolar wall damage will result in irreversible myocardial ischemia and fibrosis (“coronary Raynaud's phenomenon”).1–3

The natural history of SS is highly variable. Depending on the extent of skin involvement, SS is divided into two forms (limited and diffuse), with considerable clinical and prognostic differences. Cardiac dysfunction may be induced by various pathways, which may be either primary or secondary to lung damage (pulmonary hypertension) or through renal involvement. Both are frequent situations in these patients.1–3

In the last two decades, several authors have studied the prevalence of heart disease in SS.4,5 Follansbee et al.6 found a higher frequency of cardiac damage in diffuse forms. More recently, Tzelepis et al.,7 using cardiac MRI in a mixed SS population, found no differences in degree of myocardial fibrosis. Delayed enhancement on cardiac MRI (indicative of fibrosis) was detected in 60% of these patients. In the present case, a large area of subendocardial delayed enhancement was detected. Steen et al.,8 in a series of 953 patients, reported cardiac symptoms in 15%. Mortality due to cardiovascular causes was 20%, most of which were recorded in the first five years of follow-up. In a cohort of 1012 patients,9 35% reported cardiac symptoms, 70% of deaths were related to cardiopulmonary disease while isolated heart involvement accounted for 36% of deaths. In a large international meta-analysis10 renal, cardiac, and pulmonary involvement were described as important prognostic factors, and heart disease was present in 10% of patients (8–28% depending on the series).

The prevalence of angiographically documented coronary artery disease was reported to be similar to that in the general population (approximately 22%). Acute myocardial infarction is rare, with a rate of 1.09%.11 Nevertheless, subclinical atherosclerosis has recently been detected by multidetector computed tomography in most of these patients.12 Moreover, coronary reserve flow studies in SS have revealed a surprisingly reduced vasodilation capacity, a phenomenon that could be explained by abnormalities in small arteries.13 In the case of our patient, the coronary arteries were found to be normal, as expected in a healthy young person.

Myocardial fibrosis can lead to systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the course of the disease. However, according to data from a large registry, the prevalence of LV systolic dysfunction by Doppler echocardiography appears to be low (1.4%).14 Doppler echocardiography may underestimate specific findings compared with other measuring methods. In a recent study15 assessing LVEF by strain rate and tissue Doppler imaging, hypocontractility was frequently detected, although LVEF appeared normal by conventional Doppler. In addition to primary involvement, there are other causes of LV systolic dysfunction, such as acute myocarditis, microvascular coronary artery disease and hypertension. Acute myocarditis was reported in the early disease stages in patients with active peripheral myopathy.16 In these subjects, the clinical course can be devastating because of severe heart failure. LV diastolic dysfunction as a cause of heart failure is very common in SS, with a prevalence ranging from 27 to 60% depending on the method used to estimate it. A lower prevalence has been observed in patients under treatment with ACE inhibitors and ARBs.

RV involvement is less frequent, and is usually secondary to pulmonary hypertension. Bewley et al.17 described a rare case of SS with isolated RV dysfunction due to primary involvement. In a later study, subclinical RV systolic dysfunction was found to be more prevalent than previously thought, which become clear after using newer diagnostic modalities such as cardiac MRI, speckle-tracking-derived strain and strain rate analysis. In the present case, biventricular systolic dysfunction was found on both Doppler echocardiography and cardiac MRI.

Pericardial involvement can present in different forms, ranging from acute or chronic fibrinous pericarditis or pericardial adhesions, to effusion and pericardial tamponade. Early studies based on macroscopic observation estimated the prevalence of this involvement to be between 33% and 72%, while symptoms were less common. On histological analysis chronic pericarditis was observed in 77.5% of these individuals.18

Tachyarrhythmias and conduction defects are also usually present.19 Premature ventricular complex is the most described abnormality, with strong associations with mortality, sudden death and cardiopulmonary disease. The prevalence of supraventricular arrhythmias is around 25%. Ventricular arrhythmias have been documented in a small percentage of patients. A higher incidence of sudden death was reported in patients with myocardial and skeletal muscle abnormalities. In a prospective study, 32% had abnormal baseline electrocardiogram, left bundle branch block (16%) and first-degree atrioventricular block (8%) being the most common abnormalities.

Cardiac involvement in previously diagnosed SS patients is confirmed by standard diagnostic techniques (electrocardiography, echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, cardiac MRI). Myocardial biopsy is not commonly used.1–3

Clinical management is controversial because of the lack of randomized clinical trials, and management is generally palliative.1–3 In heart failure cases, ACE inhibitors and ARBs appear to be associated with some benefits, because of their vasodilator effects. Antiarrhythmic drugs are the mainstay therapy for SS-related arrhythmias. Beta-blockers and amiodarone are usually contraindicated in SS patients, because of Raynaud's phenomenon and risk of pulmonary fibrosis, respectively. Calcium channel blockers such as verapamil are the drug of first choice in supraventricular arrhythmias in patients with preserved ejection fraction, while amlodipine can be used in cases of Raynaud's phenomenon. Electrophysiological study and radiofrequency ablation are indicated in sustained ventricular arrhythmias recurring despite medical treatment. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators should be used in life-threatening arrhythmias. Pacemaker implantation is the only treatment in cases of severe conduction impairment. Moreover, in severe refractory cases, and in the absence of contraindications, cardiac transplantation should be considered.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.