Social media (SoMe) has a flourishing role in cardiovascular (CV) medicine as a facilitator of academic communication not only during conferences and congresses, but also by scientific societies and journals. However, there is no solid data illustrating the use of SoMe by CV healthcare professionals (CVHP) in Portugal.

Hence, the main goal of this national cross-sectional survey was to accurately characterize SoMe use by Portuguese CVHPs.

MethodsA 35-item questionnaire was specifically developed for this study, approved by the Digital Health Study Group of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology (SPC), and sent, by e-mail, to the mailing list of the SPC (including 1293 potential recipients).

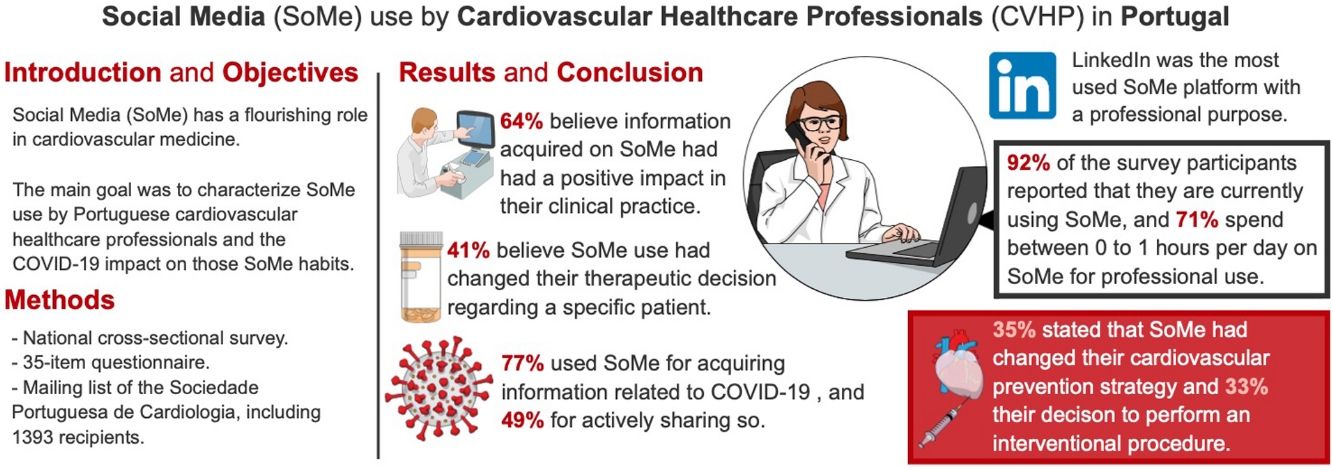

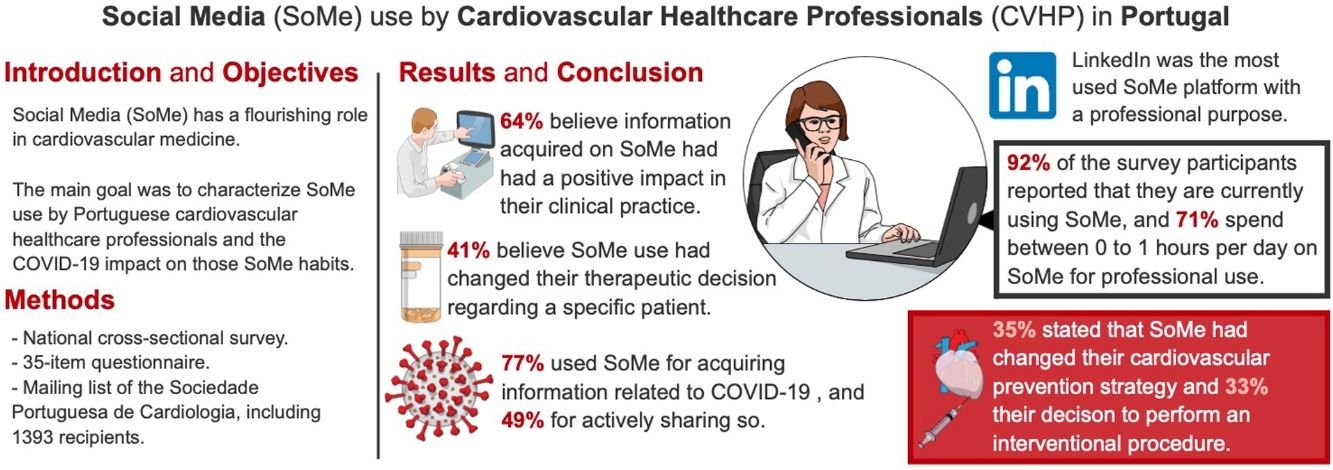

Results and conclusionThere were 206 valid answers. Fifty-two percent of respondents were female and 58% were younger than 44 years of age with almost two out of three participants being physicians. Ninety-two percent of the survey participants reported that they are currently using SoMe; LinkedIn was the most common platform used for professional purposes. Sixty-four percent believed SoMe had had a positive impact on their clinical practice; 77% and 49% had used SoMe for acquiring and sharing information related to COVID-19, respectively.

In conclusion, the majority of Portuguese CVHPs that participated in this survey are actively using SoMe, with a greater participation of those <45 years of age; its clinical impact is positive, with a leading role in the dissemination of evidence during the COVID pandemic.

As redes sociais desempenham um papel cada vez mais importante na medicina cardiovascular como facilitador da comunicação não só durante congressos científicos, mas também entre sociedades e revistas científicas. Contudo, não foi ainda caracterizado o uso das redes sociais pelos profissionais de saúde cardiovascular em Portugal. Assim, o objetivo deste inquérito de âmbito nacional foi caracterizar o uso das redes sociais pelos profissionais de saúde cardiovascular em Portugal.

MétodosFoi construído um questionário com 35 perguntas dirigido aos profissionais de saúde, que foi aprovado pelo Grupo de Estudo de Saúde Digital da Sociedade Portuguesa de Cardiologia. Esse questionário foi enviado por e-mail para a mailing list da Sociedade Portuguesa de Cardiologia, com 1293 destinatários potenciais.

Resultados e conclusãoForam obtidas 206 respostas válidas. Dos respondedores, 52% eram do sexo feminino e 58% e tinham menos de 44 anos, praticamente dois em cada três eram médicos. Dos respondedores, 92% admitiram usar redes sociais e o LinkedIn foi a plataforma mais usada no âmbito profissional. As redes sociais tiveram um papel positivo na prática clínica de 64% dos respondedores. Em relação à pandemia de Covid-19, 77% admitiram ter obtido informação pelas redes sociais e 49% partilharam informação sobre esse tópico. A maioria dos profissionais de saúde cardiovascular de Portugal que participou neste inquérito é usuária ativa das redes sociais, com uma participação preponderante dos indivíduos com menos de 45 anos; o seu impacto global sobre a prática clínica é positivo, com um papel de destaque na disseminação de evidência científica durante a pandemia de Covid-19.

Cardiovascular (CV) medicine is in constant evolution, and the role of scientific knowledge dissemination in its past, present, and future is undeniable. Throughout centuries, this diffusion occurred mainly by two essential vectors: scientific journals and in-person congresses.1 The continuous development of digital communication technologies, illustrated by the explosion of social media (SoMe), fractured this ancestral paradigm by allowing the establishment of virtual communities.2,3 As a result, SoMe has a flourishing role in CV clinical practice.

To begin with, the discussion of scientific content presented in congresses, written in guidelines, or published in journals has never been this easy. In fact, this online discussion by means of SoMe is immediate, global, does not require any type of paid subscription, and is accessible to CV healthcare professionals (CVHP) anywhere and at any time.4,5 Consequently, the academic debate is in constant eruption, quickly spreading to a larger number of participants in every corner of the globe, when compared to more traditional methods of communication. The discussion generated around the ORBITA, ISCHEMIA and FAME trials is a good example.1 It included thousands of online posts and allowed to question details concerning the protocol of these trials with a much more profound degree of minutiae that would be possible not only in the conferences where these trials were presented, but also resorting to more traditional methods of scientific literature.1,6

On the other hand, and from an academic point of view, there is a burgeoning tendency for the use of SoMe, specifically Twitter, as an auxiliary tool for the education of young cardiologists.7 There has been a gradual expansion of the concept of “#FOAMed” (free open-access medical education) and “#FITSurvivalGuide” (fellows-in-training survival guide), which consists of sharing a group of educational tweets related to a particular CV topic, using the earlier-cited hashtags.5 This conversation, which is open to and empowered by CVHP from all backgrounds and with different levels of medical education, allows for a real-time online symposium of hot CV topics.

The use of SoMe in CV clinical practice has also shown great significance regarding the academic communication not only during conferences and congresses, but also by scientific societies and journals.8,9 It has been suggested that the online promotion of CV conferences and congresses using an event-specific hashtag encourages the communication and content-sharing between its participants.10 Besides that, and being the impact factor an imperfect metric,11 the concept of Altmetric Attention Score (AAS), which is a metric automatically calculated by the attention that an article receives online, has been used as a tool to measure the impact and the performance of that same article in SoMe platforms, media, blogs and podcasts.8,12 Furthermore, it has also been demonstrated that the mention of an article in SoMe leads to an increase in its number of downloads, in-page views,13 and possibly its citations.

ObjectivesDespite the crucial role that SoMe plays in contemporary CV clinical practice, there is no solid data portraying the use of SoMe by CVHP in Portugal. Hence, the main goal of this national cross-sectional survey was to accurately characterize SoMe use by Portuguese CVHP, describing which SoMe platforms are used the most by CVHP, how much time do they spent on them, what are the reasons for their use and, also, what is the type of content that CVHP want to acquire and share while using SoMe. In addition, as a secondary objective, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on CVHP's SoMe habits was also evaluated.

MethodsA 35-item open questionnaire (available as a Supplementary file), divided in three parts, was specifically developed in Portuguese for this national cross-sectional study, inspired by questionnaires with similar objectives from different medical specialties,14–16 following the guidelines for designing questionnaires17,18 and Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).19 The first part, concerning the overall use of SoMe by CVHP, had 18 items related to: the overall pattern of SoMe use; the preferred SoMe platforms; the main reasons for its use; the type of information intended to acquire and share; the clinical impact of SoMe use and the hesitations for not using SoMe. The second part encompassed 7 items which focused on SoMe use during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as: alterations in the pattern of SoMe use; its use for searching and sharing information about COVID-19; and its use for contacting patients. The last part had questions about the demographic data of the questionnaire participants, namely: their profession, level of medical education, medical specialty, age, gender, workplace, and geographical location of the workplace.

The questionnaire was approved by the Digital Health Study Group of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology (SPC). Informed consent was provided in the first page of the questionnaire. Following its approval, the questionnaire was transposed to a Google Forms webpage and sent, by e-mail, to the mailing list of the SPC. The mailing list of the SPC was a good sample of the target audience for this questionnaire, with 1293 potential recipients, who corresponded to Portuguese CVHP and SPC members, such as: doctors, nurses, technicians, and researchers. The questionnaire was available online and collecting answers anonymously and voluntarily from 5 April 2021 until 28 April 2021. No financial compensation was provided for answering it. Every item of the questionnaire needed to be answered for it to be submitted, and, therefore, there were no missing values. Results were presented using descriptive statistics.

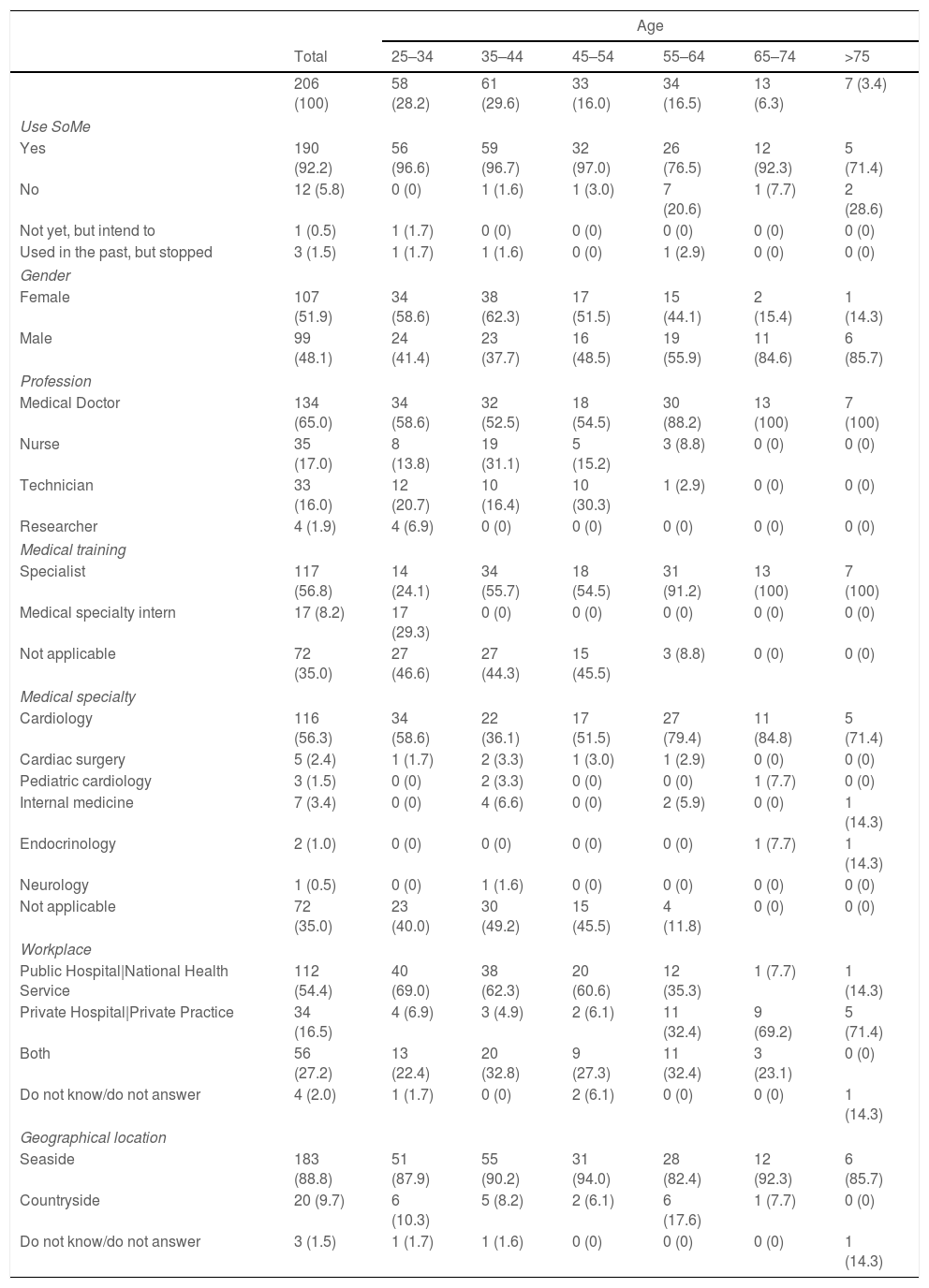

ResultsThere were 206 valid answers (survey response rate of 16%), 65.0% from physicians, 17.0% from nurses, 16.0% technicians and 1.9% researchers (Table 1). Fifty-two percent of respondents were female and 58% were younger than 44 years of age (age distribution: 28.2% between 25 and 34 years; 29.6% between 35 and 44 years; 16.0% between 45 and 54 years; 16.5% between 55 and 64 years; 6.3% between 65 and 74 years; 3.4% aged 75 years or older) (Table 1). Cardiology was the medical specialty with the most participants (56.3%), followed by internal medicine (3.4%) and cardiac surgery (2.4%) (Table 1). Most of the participants were specialists (56.8%) and 8.2% were residents. The majority of CVHP worked in a public hospital or national health service (54.4%) and in the seaside (88.8%) (Table 1).

Demographic data of the survey participants.

| Age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | >75 | |

| 206 (100) | 58 (28.2) | 61 (29.6) | 33 (16.0) | 34 (16.5) | 13 (6.3) | 7 (3.4) | |

| Use SoMe | |||||||

| Yes | 190 (92.2) | 56 (96.6) | 59 (96.7) | 32 (97.0) | 26 (76.5) | 12 (92.3) | 5 (71.4) |

| No | 12 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (3.0) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (28.6) |

| Not yet, but intend to | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Used in the past, but stopped | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 107 (51.9) | 34 (58.6) | 38 (62.3) | 17 (51.5) | 15 (44.1) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (14.3) |

| Male | 99 (48.1) | 24 (41.4) | 23 (37.7) | 16 (48.5) | 19 (55.9) | 11 (84.6) | 6 (85.7) |

| Profession | |||||||

| Medical Doctor | 134 (65.0) | 34 (58.6) | 32 (52.5) | 18 (54.5) | 30 (88.2) | 13 (100) | 7 (100) |

| Nurse | 35 (17.0) | 8 (13.8) | 19 (31.1) | 5 (15.2) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Technician | 33 (16.0) | 12 (20.7) | 10 (16.4) | 10 (30.3) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Researcher | 4 (1.9) | 4 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Medical training | |||||||

| Specialist | 117 (56.8) | 14 (24.1) | 34 (55.7) | 18 (54.5) | 31 (91.2) | 13 (100) | 7 (100) |

| Medical specialty intern | 17 (8.2) | 17 (29.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not applicable | 72 (35.0) | 27 (46.6) | 27 (44.3) | 15 (45.5) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Medical specialty | |||||||

| Cardiology | 116 (56.3) | 34 (58.6) | 22 (36.1) | 17 (51.5) | 27 (79.4) | 11 (84.8) | 5 (71.4) |

| Cardiac surgery | 5 (2.4) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pediatric cardiology | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) |

| Internal medicine | 7 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Endocrinology | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (14.3) |

| Neurology | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not applicable | 72 (35.0) | 23 (40.0) | 30 (49.2) | 15 (45.5) | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Workplace | |||||||

| Public Hospital|National Health Service | 112 (54.4) | 40 (69.0) | 38 (62.3) | 20 (60.6) | 12 (35.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (14.3) |

| Private Hospital|Private Practice | 34 (16.5) | 4 (6.9) | 3 (4.9) | 2 (6.1) | 11 (32.4) | 9 (69.2) | 5 (71.4) |

| Both | 56 (27.2) | 13 (22.4) | 20 (32.8) | 9 (27.3) | 11 (32.4) | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know/do not answer | 4 (2.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Geographical location | |||||||

| Seaside | 183 (88.8) | 51 (87.9) | 55 (90.2) | 31 (94.0) | 28 (82.4) | 12 (92.3) | 6 (85.7) |

| Countryside | 20 (9.7) | 6 (10.3) | 5 (8.2) | 2 (6.1) | 6 (17.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know/do not answer | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

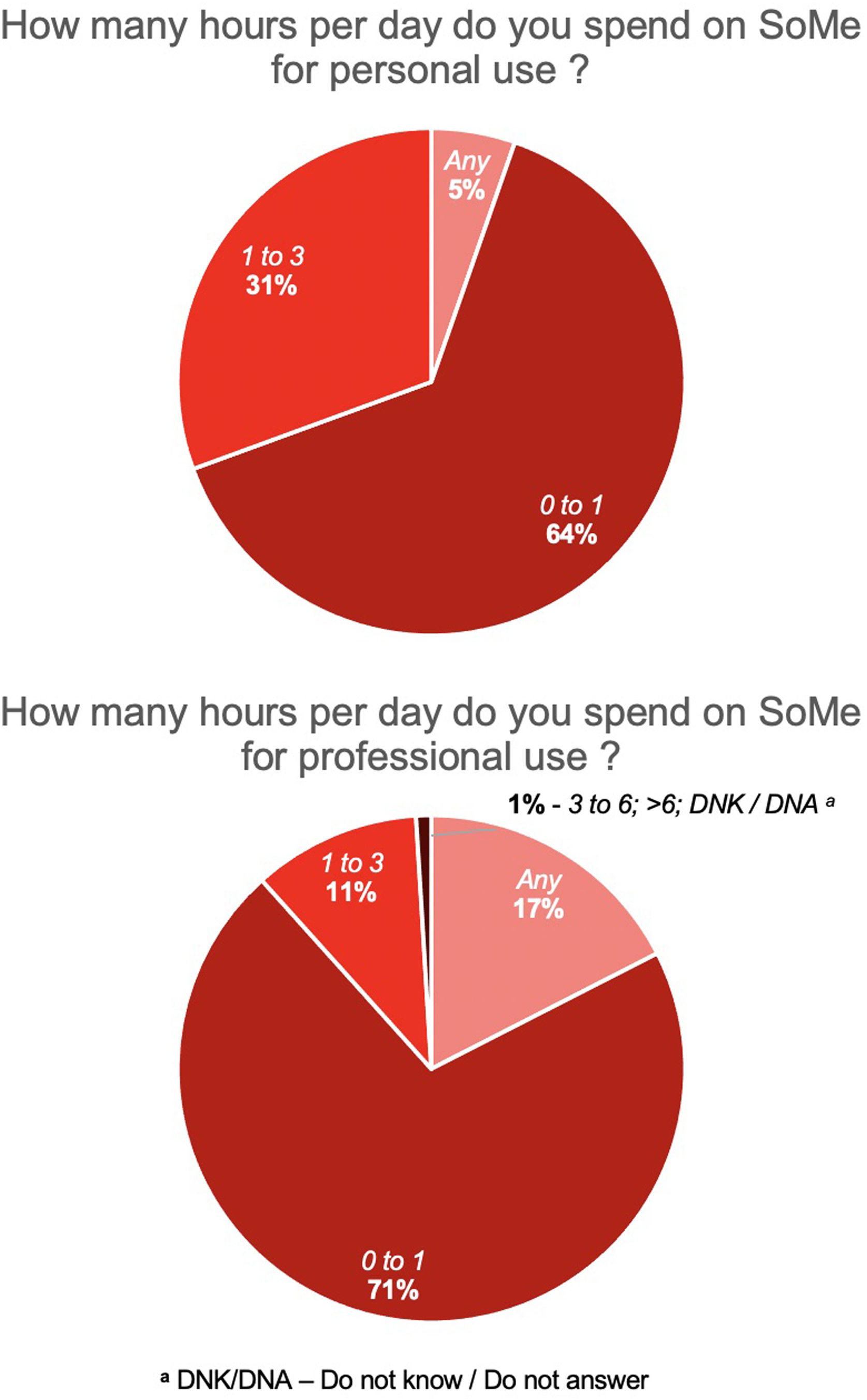

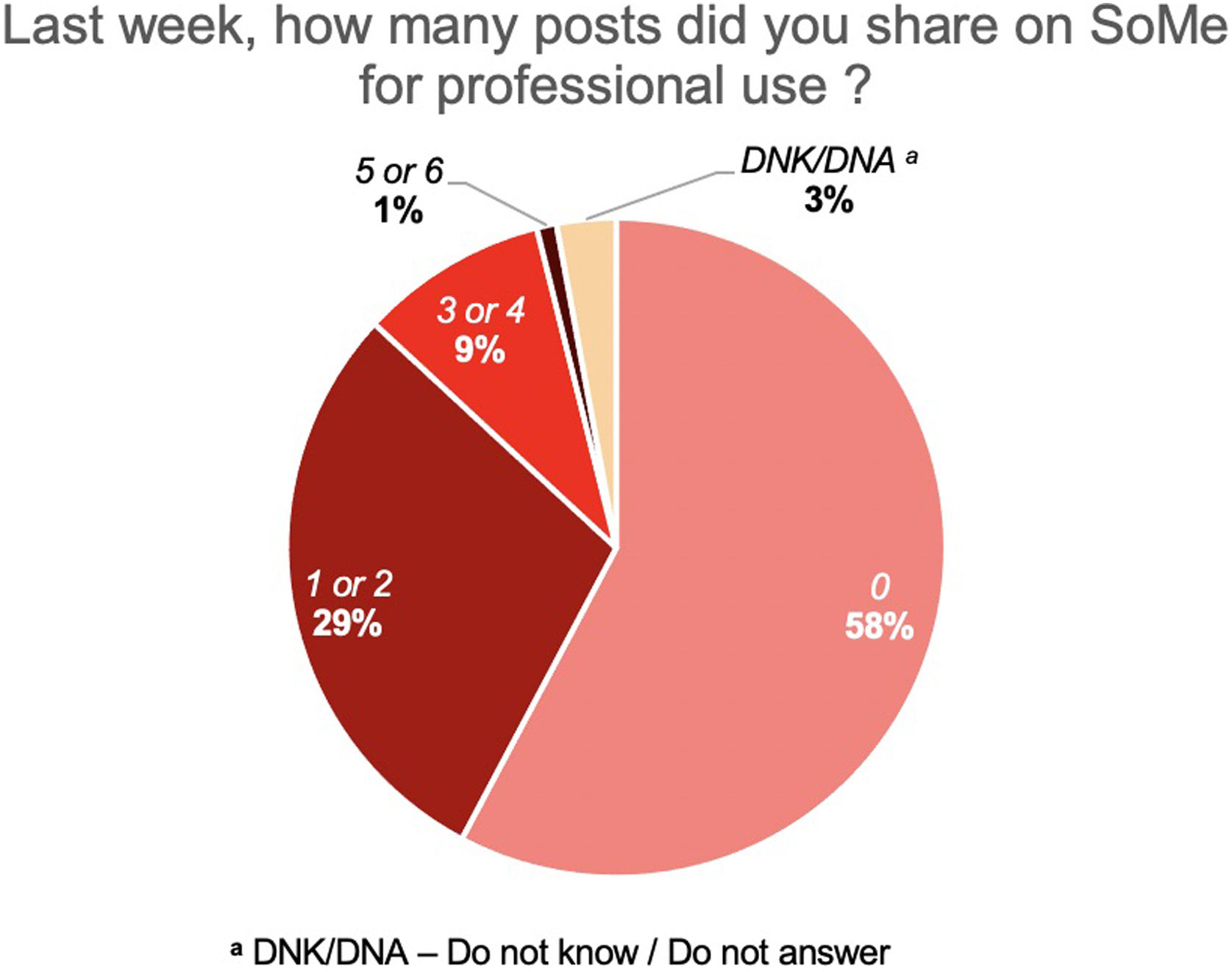

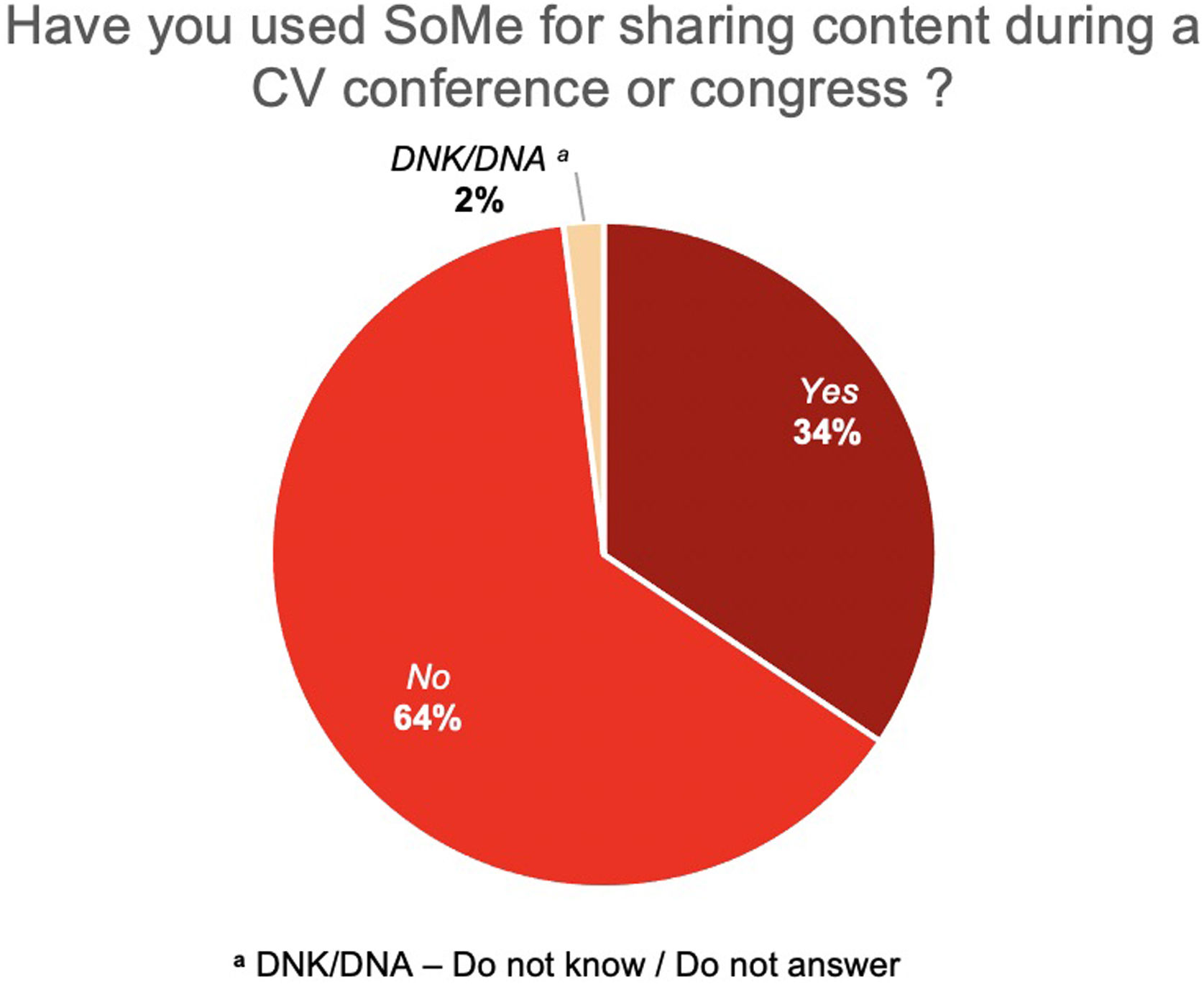

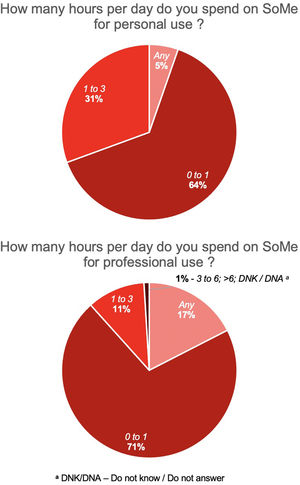

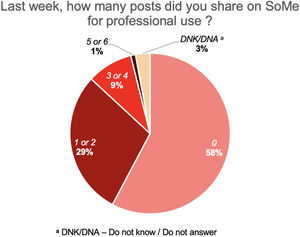

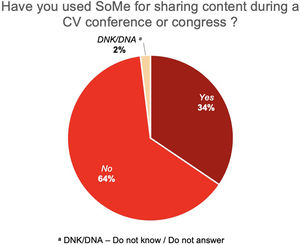

Of the 206 survey participants, 92.2% reported that they were currently using SoMe (Table 1), and most spent less than 1 hour per day on SoMe, both for professional and personal use (70.9% and 64.1%, respectively) (Figure 1). On the other hand, regarding the number of posts shared on SoMe for professional use, 39% reported having shared at least 1 post in the week before survey completion (Figure 2) and approximately 34% of CVHP have utilized SoMe for sharing content during a CV conference or congress (Figure 3).

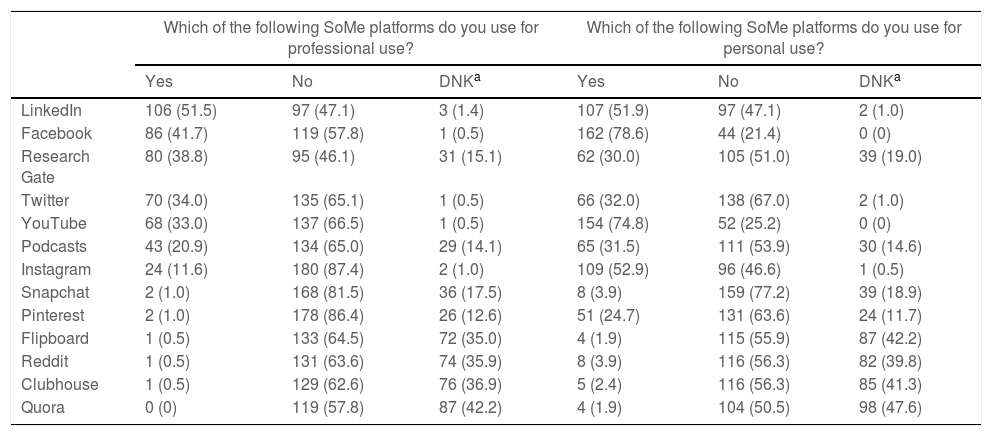

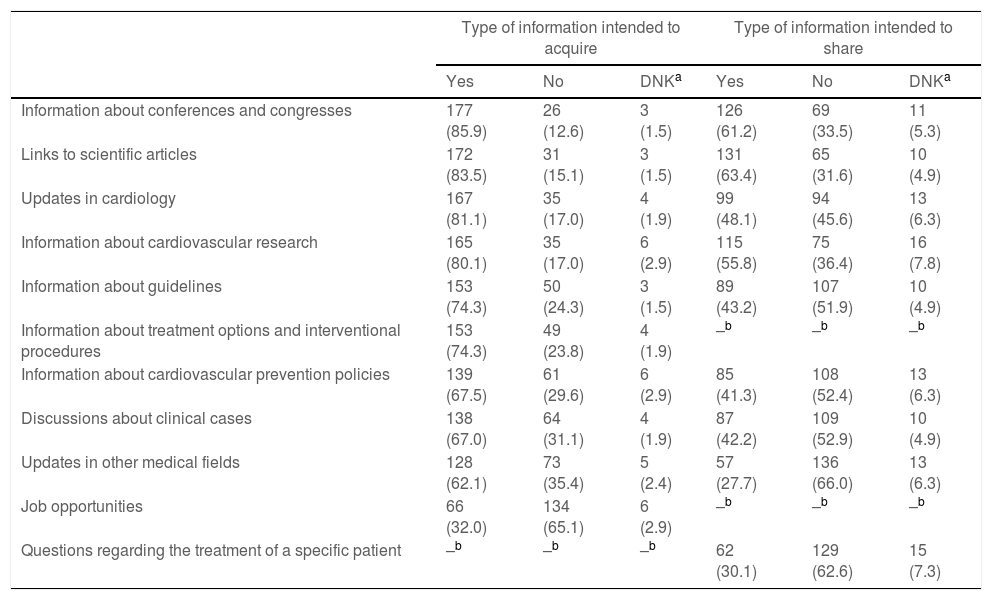

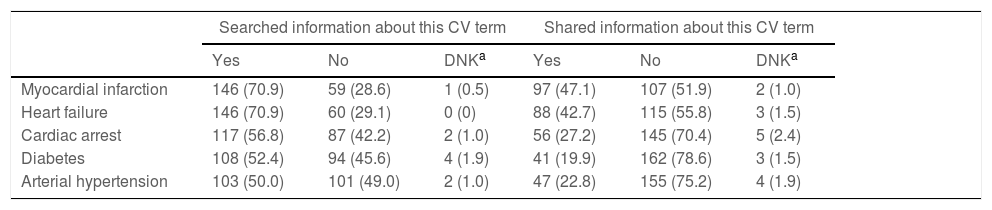

Facebook and YouTube were the SoMe platforms mostly used by CVHP for personal use (78.6% and 74.8%, respectively), and LinkedIn (51.5%), Facebook (41.7%), and ResearchGate (38.8%) were the ones mostly used for professional use (Table 2). Although Podcasts were not, per se, a SoMe platform, 31.5% of participants were listening to them with a personal purpose and 20.9% with a professional purpose. More than 80% of the survey participants used SoMe to acquire information about conferences and congresses (85.9%), links to scientific articles (83.5%), updates in cardiology (81.1%) and information about CV research (80.1%) (Table 3). Adding information about guidelines also made the top five of the type of information CVHP intended to share the most while using SoMe (Table 3). Heart failure and myocardial infarction were the most searched topics (70.9%) and shared (42.7% and 47.1%, respectively) CV topics on SoMe (Table 4).

Social media platforms used by cardiovascular healthcare professionals.

| Which of the following SoMe platforms do you use for professional use? | Which of the following SoMe platforms do you use for personal use? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | DNKa | Yes | No | DNKa | |

| 106 (51.5) | 97 (47.1) | 3 (1.4) | 107 (51.9) | 97 (47.1) | 2 (1.0) | |

| 86 (41.7) | 119 (57.8) | 1 (0.5) | 162 (78.6) | 44 (21.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Research Gate | 80 (38.8) | 95 (46.1) | 31 (15.1) | 62 (30.0) | 105 (51.0) | 39 (19.0) |

| 70 (34.0) | 135 (65.1) | 1 (0.5) | 66 (32.0) | 138 (67.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| YouTube | 68 (33.0) | 137 (66.5) | 1 (0.5) | 154 (74.8) | 52 (25.2) | 0 (0) |

| Podcasts | 43 (20.9) | 134 (65.0) | 29 (14.1) | 65 (31.5) | 111 (53.9) | 30 (14.6) |

| 24 (11.6) | 180 (87.4) | 2 (1.0) | 109 (52.9) | 96 (46.6) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Snapchat | 2 (1.0) | 168 (81.5) | 36 (17.5) | 8 (3.9) | 159 (77.2) | 39 (18.9) |

| 2 (1.0) | 178 (86.4) | 26 (12.6) | 51 (24.7) | 131 (63.6) | 24 (11.7) | |

| 1 (0.5) | 133 (64.5) | 72 (35.0) | 4 (1.9) | 115 (55.9) | 87 (42.2) | |

| 1 (0.5) | 131 (63.6) | 74 (35.9) | 8 (3.9) | 116 (56.3) | 82 (39.8) | |

| Clubhouse | 1 (0.5) | 129 (62.6) | 76 (36.9) | 5 (2.4) | 116 (56.3) | 85 (41.3) |

| Quora | 0 (0) | 119 (57.8) | 87 (42.2) | 4 (1.9) | 104 (50.5) | 98 (47.6) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

Social media content.

| Type of information intended to acquire | Type of information intended to share | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | DNKa | Yes | No | DNKa | |

| Information about conferences and congresses | 177 (85.9) | 26 (12.6) | 3 (1.5) | 126 (61.2) | 69 (33.5) | 11 (5.3) |

| Links to scientific articles | 172 (83.5) | 31 (15.1) | 3 (1.5) | 131 (63.4) | 65 (31.6) | 10 (4.9) |

| Updates in cardiology | 167 (81.1) | 35 (17.0) | 4 (1.9) | 99 (48.1) | 94 (45.6) | 13 (6.3) |

| Information about cardiovascular research | 165 (80.1) | 35 (17.0) | 6 (2.9) | 115 (55.8) | 75 (36.4) | 16 (7.8) |

| Information about guidelines | 153 (74.3) | 50 (24.3) | 3 (1.5) | 89 (43.2) | 107 (51.9) | 10 (4.9) |

| Information about treatment options and interventional procedures | 153 (74.3) | 49 (23.8) | 4 (1.9) | –b | –b | –b |

| Information about cardiovascular prevention policies | 139 (67.5) | 61 (29.6) | 6 (2.9) | 85 (41.3) | 108 (52.4) | 13 (6.3) |

| Discussions about clinical cases | 138 (67.0) | 64 (31.1) | 4 (1.9) | 87 (42.2) | 109 (52.9) | 10 (4.9) |

| Updates in other medical fields | 128 (62.1) | 73 (35.4) | 5 (2.4) | 57 (27.7) | 136 (66.0) | 13 (6.3) |

| Job opportunities | 66 (32.0) | 134 (65.1) | 6 (2.9) | –b | –b | –b |

| Questions regarding the treatment of a specific patient | –b | –b | –b | 62 (30.1) | 129 (62.6) | 15 (7.3) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

Cardiovascular terms on social media.

| Searched information about this CV term | Shared information about this CV term | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | DNKa | Yes | No | DNKa | |

| Myocardial infarction | 146 (70.9) | 59 (28.6) | 1 (0.5) | 97 (47.1) | 107 (51.9) | 2 (1.0) |

| Heart failure | 146 (70.9) | 60 (29.1) | 0 (0) | 88 (42.7) | 115 (55.8) | 3 (1.5) |

| Cardiac arrest | 117 (56.8) | 87 (42.2) | 2 (1.0) | 56 (27.2) | 145 (70.4) | 5 (2.4) |

| Diabetes | 108 (52.4) | 94 (45.6) | 4 (1.9) | 41 (19.9) | 162 (78.6) | 3 (1.5) |

| Arterial hypertension | 103 (50.0) | 101 (49.0) | 2 (1.0) | 47 (22.8) | 155 (75.2) | 4 (1.9) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

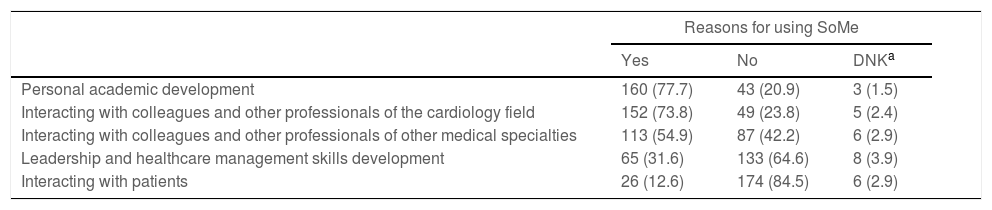

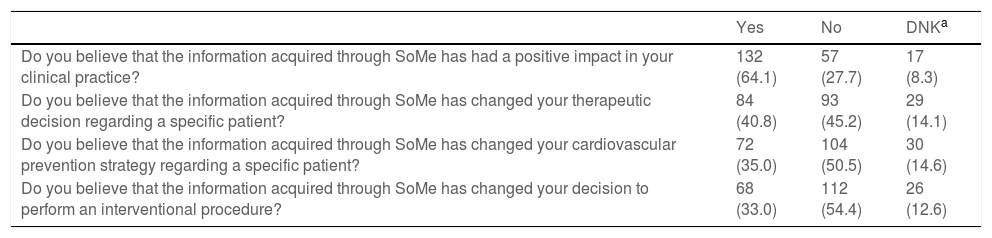

Personal academic development (77.7%) and interacting with colleagues and other professionals in the cardiology field (73.8%) were the principal reasons appointed by CVHP for using SoMe professionally (Table 5). Only 12.6% of CVHP contemplated interacting with patients as reason for its use (Table 5). Concerning the clinical impact of SoMe use, 64.1% of participants believed that the information acquired through SoMe had had a positive impact on their clinical practice. In addition, 40.8% believed it had changed their therapeutic decision regarding a specific patient and more than 30% believed that this method of communication had changed both their CV prevention strategy regarding a specific patient (35.0%) and their decision to perform an interventional procedure (33.0%) (Table 6).

Reasons for using social media in a professional context.

| Reasons for using SoMe | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | DNKa | |

| Personal academic development | 160 (77.7) | 43 (20.9) | 3 (1.5) |

| Interacting with colleagues and other professionals of the cardiology field | 152 (73.8) | 49 (23.8) | 5 (2.4) |

| Interacting with colleagues and other professionals of other medical specialties | 113 (54.9) | 87 (42.2) | 6 (2.9) |

| Leadership and healthcare management skills development | 65 (31.6) | 133 (64.6) | 8 (3.9) |

| Interacting with patients | 26 (12.6) | 174 (84.5) | 6 (2.9) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

Clinical impact of social media use.

| Yes | No | DNKa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you believe that the information acquired through SoMe has had a positive impact in your clinical practice? | 132 (64.1) | 57 (27.7) | 17 (8.3) |

| Do you believe that the information acquired through SoMe has changed your therapeutic decision regarding a specific patient? | 84 (40.8) | 93 (45.2) | 29 (14.1) |

| Do you believe that the information acquired through SoMe has changed your cardiovascular prevention strategy regarding a specific patient? | 72 (35.0) | 104 (50.5) | 30 (14.6) |

| Do you believe that the information acquired through SoMe has changed your decision to perform an interventional procedure? | 68 (33.0) | 112 (54.4) | 26 (12.6) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

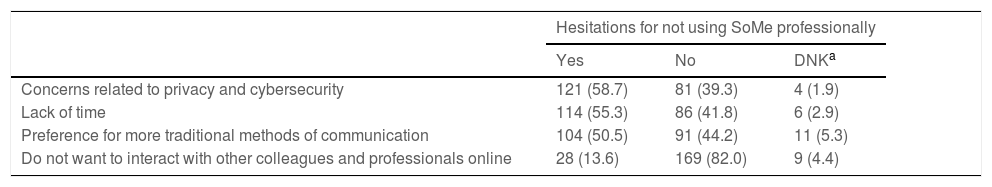

Regarding the hesitations for not using SoMe professionally, 58.7% presented concerns related to privacy and cybersecurity, 55.3% described the lack of time as a limiting factor, and close to 50% expressed a preference for more traditional methods of communication (Table 7).

Social media use hesitations.

| Hesitations for not using SoMe professionally | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | DNKa | |

| Concerns related to privacy and cybersecurity | 121 (58.7) | 81 (39.3) | 4 (1.9) |

| Lack of time | 114 (55.3) | 86 (41.8) | 6 (2.9) |

| Preference for more traditional methods of communication | 104 (50.5) | 91 (44.2) | 11 (5.3) |

| Do not want to interact with other colleagues and professionals online | 28 (13.6) | 169 (82.0) | 9 (4.4) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

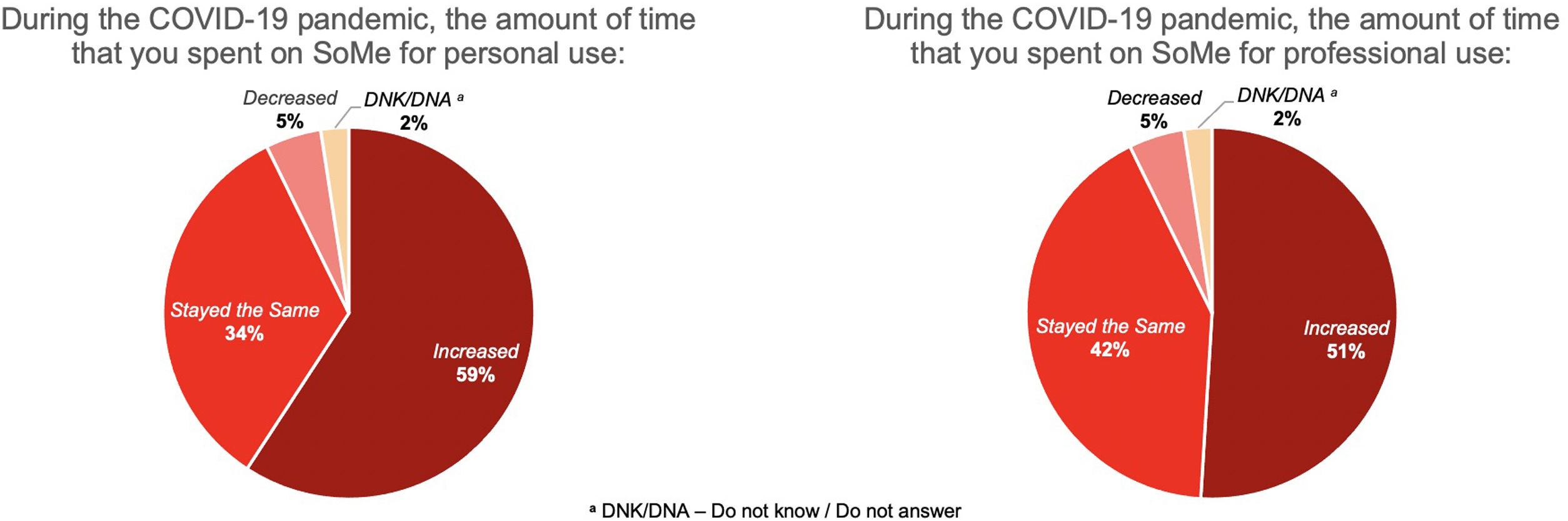

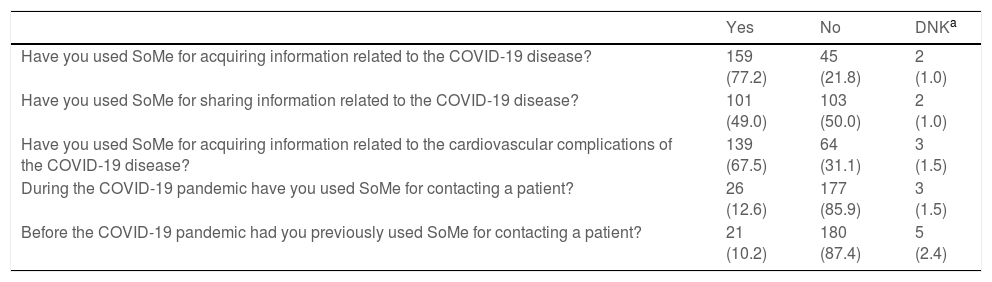

The COVID-19 pandemic also affected the way CVHP communicate with each other by means of SoMe. In fact, 59% of the participants cited an increase in the time spent on SoMe for personal use during the pandemic, and 51% mentioned an increase in the time spent for professional use (Figure 4). Furthermore, 77% and 49% suggested having used SoMe for acquiring and sharing information related to COVID-19, respectively (Table 8). More specifically, 67.5% of CVHP used SoMe for searching information related to the CV complications of COVID-19 (Table 8).

Social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Yes | No | DNKa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you used SoMe for acquiring information related to the COVID-19 disease? | 159 (77.2) | 45 (21.8) | 2 (1.0) |

| Have you used SoMe for sharing information related to the COVID-19 disease? | 101 (49.0) | 103 (50.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Have you used SoMe for acquiring information related to the cardiovascular complications of the COVID-19 disease? | 139 (67.5) | 64 (31.1) | 3 (1.5) |

| During the COVID-19 pandemic have you used SoMe for contacting a patient? | 26 (12.6) | 177 (85.9) | 3 (1.5) |

| Before the COVID-19 pandemic had you previously used SoMe for contacting a patient? | 21 (10.2) | 180 (87.4) | 5 (2.4) |

Results presented as: No. participants (%).

This is the first survey focused on describing and characterizing social media use by CV healthcare professionals in Portugal. Overall, the majority of Portuguese CVHP that participated in this survey are actively using SoMe, mostly LinkedIn and Facebook, with a greater participation of those <45 years of age. While LinkedIn, Facebook and Research Gate were the SoMe platforms mostly used for professional use (51.5%; 41.7% and 38.8%, respectively), Facebook, YouTube and Instagram (78.6%; 74.8% and 52.9%, respectively) were the main ones used for personal use (Table 2). Interestingly, Twitter was only in the fourth position of the most used social media platforms for professional use (34.0%). We emphasize that this platform is the main focus of the European Society of Cardiology social media activities, as detailed in a recently published review article.20 Therefore, we suggest its widespread adoption as one of the preferred social media platforms for medical education and research dissemination.

The results of our national cross-sectional survey suggest that the Portuguese CVHP were, at the time of completion, using SoMe in the same or even slightly higher proportion than the majority of international healthcare providers20,21 and for a similar time period, per day.21 As for the SoMe platforms used, there is a relative underuse of Twitter for professional use when compared to other international healthcare professionals,7,14,20,22 which might be explained by the overall low use of Twitter in Portugal.23 In fact, according to a recent review, Twitter appears to be the SoMe platform most adequate for professional use and that is supported by international scientific societies.10,20,24 LinkedIn and Facebook were the main services used with a professional intention, as it was the case of two similar cross-sectional studies reporting the SoMe use patterns by Oncology and Neurosurgery professionals, respectively.14,15

Most of the participants considered that the information acquired through SoMe had had a positive impact in their clinical practice, visibly illustrating the influence of SoMe in current Portuguese CV medicine. Indeed, SoMe is nowadays regarded as a communication channel for medical education and research dissemination, therefore of meaningful value for clinical practice, with striking examples of cardiological procedures that were amplified through SoMe (especially Twitter), more evident in the electrophysiology and interventional cardiology subspecialties.20,25,26 However, although the majority of the participants reported that information acquired through SoMe had had a positive impact pn their clinical practice, less than half reported changes in terms of the approach to specific cases or the application of interventional procedures (35.0% and 33.0%, respectively). Several factors may contribute to this and represent some of the concerns regarding SoMe,20 probably topped by the fear of inaccurate or biased information that could lead to medical malpractice.

The importance of SoMe in CV academia and research is undeniable20 and supported by our results. They show that personal academic development and interaction with colleagues from the cardiology field were the principal reasons for using SoMe. This is similarly accentuated by the top four topics of information sought by Portuguese CVHP, including information about conferences and congresses, links to scientific articles, updates in cardiology and information about CV research. There is an increasing interest on the role of SoMe platforms and especially Twitter on the academic community, with some evidence suggesting that mentioning an article on Twitter, compared to other SoMe platforms, has the highest correlation with the number of downloads of that same article.12 Another example of this importance is the controversy launched on Twitter about the His-bundle pacing. Curiously, in 2019, Beer et al. showed a positive association between the impressions (tweets×number of followers) with the hashtag “#dontdisthehis” and the number of pacing procedures using the His-bundle.25

From a purely clinical perspective, almost two-thirds of respondents felt the information acquired through SoMe had had a positive impact in their clinical practice. This is a meaningful number describing the importance of SoMe for Portuguese CVHP. Adding to this, we can also stress the high proportion of CVHP using SoMe for actively searching and sharing information about COVID-19 and the overall increase in SoMe use during that same period, as it was the case reported by other healthcare professionals in other countries.27–30 As an example, in a cross-sectional survey conducted in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic.27 Murry et al. reported that 47% of the respondents stated that information shared on SoMe had a consistent impact on their daily clinical practice. This is a lower proportion in comparison with our results, but the study was focused on COVID-19 pandemic and therefore the fear of misinformation could partially account for it.

The limitations of our study arise from it being focused on an online survey, therefore the respondents may have been more prone to using digital communication technologies, including SoMe. Thus, our results about SoMe use can be somewhat overestimated. In fact, more than half of the respondents reported concerns related to privacy and cybersecurity has a hesitation for using SoMe, therefore choosing more traditional methods of communication. These results highlight the potential downsides of SoMe utilization by healthcare professionals, such as the non-professional use of SoMe platforms, the danger of breaching confidentiality and threatening patient-physician relationships, privacy concerns and the concept of a “filter bubble” (something described by Pariser in 2010, in which users are preferentially offered articles and posts to support their current opinions and perspectives, based on past searches, click behavior and location) and the fear of inaccurate or biased information.20 In addition, this was a survey conducted in Portugal and, hence, our results cannot be directly extrapolated to other countries.

ConclusionIn conclusion, our results support the clinical and academic importance of SoMe use by CVHP in Portugal. The majority of Portuguese CVHPs that participated in this survey are actively using SoMe and the opinion regarding its impact in clinical practice is positive. The Portuguese community of healthcare professionals dedicated to CV care should increasingly and responsibly use social media platforms (especially Twitter), following the trend of most international societies, with the goal of improving the communication and dissemination of information and eventually leading to better patient care.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to acknowledge all the Portuguese CVHPs who answered the questionnaire for making this survey possible.