The Portuguese National Registry of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation records prospectively the characteristics and outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) procedures in Portugal.

ObjectivesTo assess the 30-day and one-year outcomes of TAVI procedures in Portugal.

MethodsWe compared TAVI results according to the principal access used (transfemoral (TF) vs. non-transfemoral (non-TF)). Cumulative survival curves according to access route, other procedural and clinical variables were obtained. The Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) composite endpoint of early (30-days) safety was assessed. VARC-2 predictors of 30-days and 1-year all-cause mortality were identified.

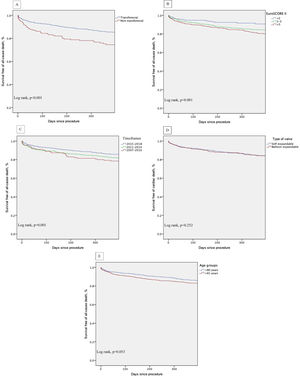

ResultsBetween January 2007 and December 2018, 2346 consecutive patients underwent TAVI (2242 native, 104 valve-in-valve; mean age 81±7 years, 53.2% female, EuroSCORE-II - EuroS-II, 4.3%). Device success was 90.1% and numerically lower for non-TF (87.0%). Thirty-day all-cause mortality was 4.8%, with the TF route rendering a lower mortality rate (4.3% vs. 10.1%, p=0.001) and higher safety endpoint (86.4% vs. 72.6%, p<0.001). The one-year all-cause mortality rate was 11.4%, and was significantly lower for TF patients (10.5% vs. 19.4%, p<0.002). After multivariate analysis, peripheral artery disease, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, left ventricular dysfunction and NYHA class III-IV were independent predictors of 30-day all-cause mortality. At one-year follow-up, NYHA class III-IV, non-TF route and occurrence of life-threatening bleeding predicted mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the first year of follow-up shows decreased survival for patients with an EuroS-II>5% (p<0.001) and who underwent non-TF TAVI (p<0.001).

ConclusionData from our national real-world registry showed that TAVI was safe and effective. The use of a non-transfemoral approach demonstrated safety in the short term. Long-term prognosis was, however, adversely associated with this route, with comorbidities and the baseline clinical status.

O Registo Nacional de Cardiologia de Intervenção de Válvulas Aórticas Percutâneas (RNCI-VaP) documenta prospetivamente as características e resultados da VAP em Portugal.

ObjetivosAvaliar os resultados a 30 dias e um ano da VAP em Portugal.

MétodosComparação dos resultados da VAP de acordo com o acesso (transfemoral – TF versus não transfemoral – não TF). Obtiveram-se curvas de sobrevivência cumulativa de acordo com o acesso, variáveis do procedimento e clínicas. Avaliou-se a segurança precoce (30 dias) do procedimento, de acordo com os critérios Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2). Identificaram-se preditores de mortalidade a 30 dias e um ano.

ResultadosEntre janeiro 2007 e dezembro 2018, realizaram-se 2346 VAP (2242 nativas, 104 Valve-in-Valve [VIV]; idade média 81±7 anos, 53,2% mulheres, EuroSCORE-II [EuroS-II] 4,3%). Sucesso do dispositivo foi obtido em 90,1%, inferior para o não TF (87,0%). Aos 30 dias, a mortalidade global foi de 4,8%, apresentando o TF menor mortalidade (4,3% versus 10,1%, p=0,001) e maior segurança (86,4% versus 72,6%, p<0,001). A mortalidade a um ano foi 11,4%, significativamente menor para o TF (10,5% versus 19,4%, p<0,002). Após análise multivariável, identificaram-se como preditores de mortalidade a 30 dias doença arterial periférica, angioplastia prévia, disfunção ventricular esquerda e classe NYHA III-IV. A um ano, NYHA III-IV, o acesso não TF e a hemorragia com risco de vida foram preditores de mortalidade. A análise de sobrevivência a um ano evidenciou menor sobrevivência para EuroS-II>5% (p<0,001) e VAP não TF (p<0,001).

ConclusõesDados do RNCI-VaP mostram que a VAP foi segura e eficaz. O acesso não TF mostrou segurança em curto prazo. O prognóstico em longo prazo foi influenciado negativamente por este acesso, assim como comorbilidades e o estado clínico de base do doente.

Severe aortic stenosis (AS) is the most prevalent type of valvular heart disease in the western world,1 with particular high prevalence in older patients.2 Global demography shows a pattern of an aging population and since 1960 life expectancy at birth in Portugal has increased from 64 to 82 years. This will increase the burden of AS and the need to treat it.3,4 Surgical aortic valve (SAV) replacement is an established treatment for symptomatic severe AS.5 However, in the last decade, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as a minimally invasive treatment for AS, initially for inoperable and high risk patients6 but increasingly, as evidence grows, it is used in lower risk patients.7,8 Evidence is building on the durability of transcatheter aortic valves, with over 90% of patients remaining free of structural valve dysfunction between five and 10 years post-implantation.9 This may encourage increased use of this technology in younger and lower risk patients. Growing experience, solid evidence, refined pre-procedural assessment with multi-slice computed-tomography (MSCT) and new generation transcatheter devices are causing a shift toward new indications, including lower-surgical risk patients.10,11

Transfemoral (TF) access is the preferred route, since it is less invasive, and patient recovery is faster, involving shorter hospital stays.12 Nevertheless, up to one third of eligible patients may not be appropriate candidates for a TF approach because of major peripheral artery disease (PAD). Other routes have emerged as alternatives, but are associated with worse outcomes, particularly when considering the transapical (TA) route.13

Another field of increasing importance in TAVI is prosthetic valve dysfunction (PVD). Currently, patients with previously implanted biological SAV can be treated with a valve-in-valve (ViV) procedure for PVD, which has been associated with good one-year outcomes.14

Registries have reported the results of TAVI in several countries, showing consistently high implantation success rates; a recent meta-analysis reported an overall European 30-day mortality of 8%, however with substantial differences among registries.15,16 Mid- and long-term follow-up results show survival rates over 80% at one year, with persistent improvement of clinical status.17

The Portuguese National Registry of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (RNCI-VaP) is a national registry conducted with the main purpose of assessing all comers with aortic valve disease or aortic valve prosthesis dysfunction that undergo TAVI in Portugal, ensuring comprehensive coverage in Portugal.18 The main goals of the registry are to document in a prospective and consecutive fashion the characteristics of patients who undergo TAVI, ascertain the results of these treatments in Portugal, develop scientific work based on data included in the registry, establish treatment recommendations regarding TAVI procedures and collaborate with other similar international registries. A position paper statement from the Portuguese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention (APIC) has already underlined the importance of a systematic assessment and report of patients who undergo TAVI in Portugal.19 The members of this committee are all interventional cardiologists. It is divided into an executive board of three members which includes the Registry Coordinator and the scientific board. There is no specific funding for this registry which has been completely developed, maintained and sponsored by APIC.

This article is the first report of real-world clinical data from the RNCI-VaP registry. It aims to identify patient and procedure characteristics and evaluate 30-day and one-year outcomes of TAVI in Portugal.

MethodsPatient selectionThe RNCI-VaP is a continuous, observational and prospective registry, which began in 2007. A total of 14 exclusively Portuguese private and public centers participated in the registry on a voluntary basis. Registry data inclusion and analysis are the exclusive responsibility of the members of the RNCI-VaP, which is free from industry body influence. The registry complies with Portuguese data protection laws and was approved by a central ethics board. All patients gave written informed consent.

Selection of symptomatic patients with severe AS or PVD for TAVI followed a multidisciplinary approach in which all individual cases were discussed within a heart team and the procedures performed in hospitals with on-site cardiac surgery.20 Patients were included if considered high risk for traditional aortic valve replacement (AVR) surgery or deemed inoperable. Patients were excluded if their life expectancy with TAVI was ≤1 year or the patient's quality of life was unlikely to improve with TAVI. MSCT was routinely performed to select the access route, and aspects such as size, tortuosity and calcification were assessed. If a femoral approach was not possible, an alternative access was planned (transcarotid, transaortic, transubclavian or transapical). MSCT data also enabled characterization of the aortic annulus and valve, sinus of Valsalva, coronary ostia and ascending aorta. The decision regarding the access route, the prosthesis type and size were made according to each center's routine, taking into consideration the clinical and morphological assessment. At all TAVI centers, the procedure was performed with the support of at least one anesthesiologist.

Data acquisition and quality controlData were entered into a dedicated database and sent to the National Cardiology Data Collection Center of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology. Events and values collected are site reported, and there are no core laboratories. Data were examined and validated, and the participating centers contacted in the event of any queries or discrepancies. Supervision of the RNCI-VaP is the responsibility of the principal investigators (A.L., A.F., B.S., E.I.O., E.J., F.S., J.S., J.S.M., L.R., R.C., S.B.) and the registry coordinator (R.C.T.).

Study variables and outcomesStudy variables were based on the recommendations of the updated VARC-2 consensus document.21 They included the following in-hospital and 30-days outcomes: i) immediate procedural mortality (up to 72 hours post-procedure); ii) procedural mortality (all-cause mortality within 30 days or during index procedure hospitalization if the postoperative length of stay was longer than 30 days); iii) early (30 days) safety (defined as freedom from all-cause mortality, all stroke, life-threatening bleeding, acute kidney injury stage 2 or 3, coronary artery obstruction requiring intervention, major vascular complication and valve-related dysfunction requiring a repeat procedure); iv) myocardial infarction; v) stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA); vi) bleeding complications (defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria); vii) acute kidney injury (acute kidney injury network classification); viii) vascular complications; ix) other TAVI-related complications. All-cause mortality was assessed at 30 days and at one-year follow-up. Prospective follow-up of adverse events was reported by the investigators. At 30-days and one-year, 48 (2%) and 530 (22%) patients, respectively, were lost to follow-up.

Device descriptionThe national registry is open to any type of commercial device. To date, 12 different valves and their iterations have been used including: Medtronic CoreValve™, Edwards Sapien™, Abbott Portico™, Boston Scientific Acurate neo™ and Lotus Edge™, Direct Flow Medical™, NVT Allegra TAVI System TF™, and Medtronic Engager™. The technical specifications of these devices have been described elsewhere.22

Statistical analysisDistribution of continuous variables was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test and they are expressed as mean ± SD or as median ± IQR, where appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired Student's t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables.

Multivariate analysis for the prediction of all-cause mortality during 30-days and one-year follow-up was performed using Cox regression, by including all statistically significant variables in the univariate analysis and those considered clinically relevant. The results are expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%). Survival curves were obtained with the Kaplan-Meier method. A log-rank test was used to compare survival between groups during follow-up.

A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistics software (version 23.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

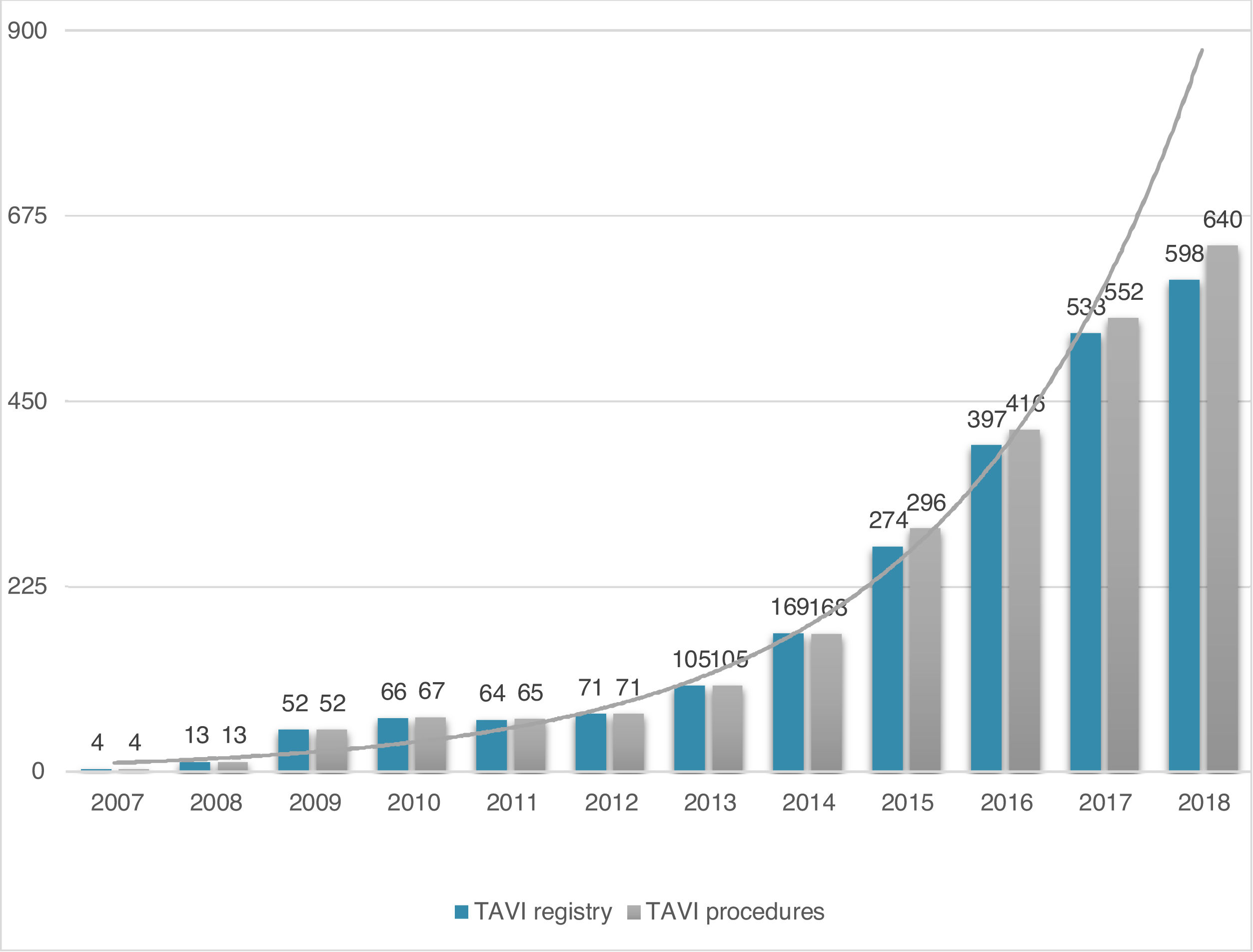

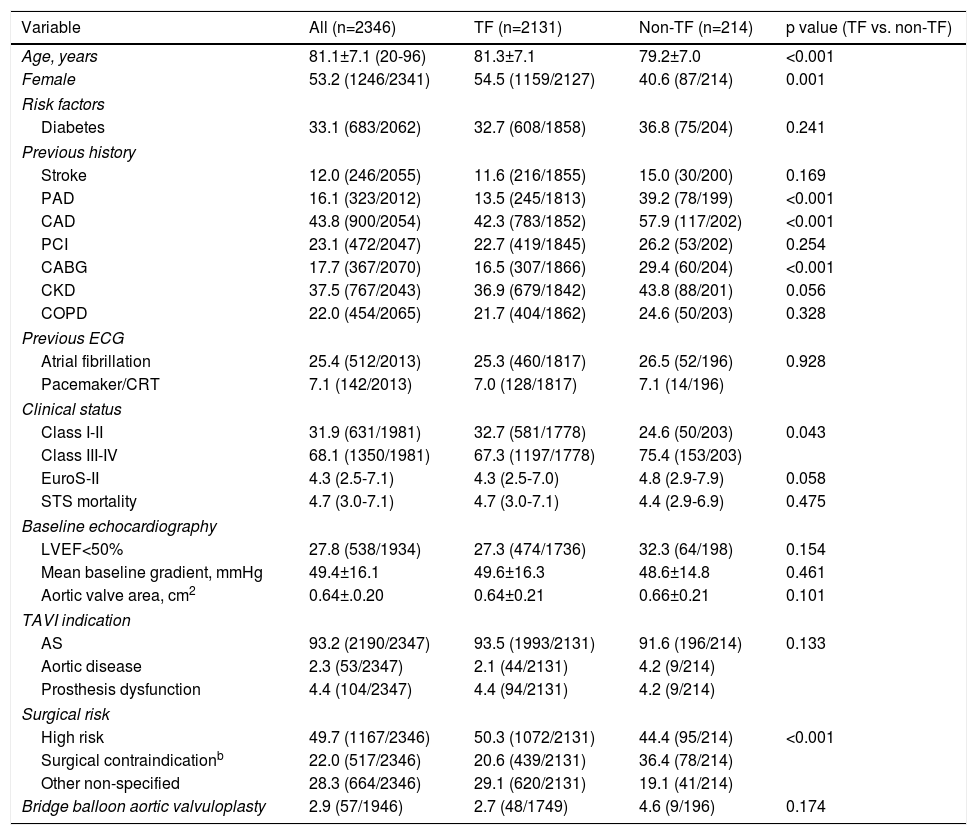

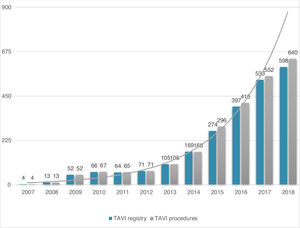

ResultsStudy populationPatient population and procedural characteristics. From January 2007 to December 2018, a total of 2346 consecutive patients were included in the Portuguese National Registry of TAVI, with no exclusion criteria. In the last 10 years, there has been an exponential increase in the number of procedures performed, with a slight deceleration in 2018, as illustrated in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of our global cohort was 81±7 years with the youngest and oldest patients aged 20 and 96, respectively. The median EuroS-II was 4.3% (IQR 2.5-7.1) and the STS score mortality risk was 4.7% (IQR 3.0-7.1). The majority of patients were in NYHA functional class III or IV (68.1%). The predominant route was transfemoral (90.9%). Self-expandable valves (SEV), particularly Medtronic CoreValve, were used more frequently (69.1%), while the remaining 30.9% were balloon-expandable (BEV) Edwards Valves. Procedural characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Evolution in the number of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) procedures in Portugal since the beginning of the Portuguese Registry of TAVI in 2007 until the end of 2018 (data presented in number of procedures per year; n=2380 global TAVI procedures; n=2346 TAVI procedures in the registry).

Baseline characteristics of the study population and according to the transcatheter aortic valve implantation access route.a

| Variable | All (n=2346) | TF (n=2131) | Non-TF (n=214) | p value (TF vs. non-TF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 81.1±7.1 (20-96) | 81.3±7.1 | 79.2±7.0 | <0.001 |

| Female | 53.2 (1246/2341) | 54.5 (1159/2127) | 40.6 (87/214) | 0.001 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Diabetes | 33.1 (683/2062) | 32.7 (608/1858) | 36.8 (75/204) | 0.241 |

| Previous history | ||||

| Stroke | 12.0 (246/2055) | 11.6 (216/1855) | 15.0 (30/200) | 0.169 |

| PAD | 16.1 (323/2012) | 13.5 (245/1813) | 39.2 (78/199) | <0.001 |

| CAD | 43.8 (900/2054) | 42.3 (783/1852) | 57.9 (117/202) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 23.1 (472/2047) | 22.7 (419/1845) | 26.2 (53/202) | 0.254 |

| CABG | 17.7 (367/2070) | 16.5 (307/1866) | 29.4 (60/204) | <0.001 |

| CKD | 37.5 (767/2043) | 36.9 (679/1842) | 43.8 (88/201) | 0.056 |

| COPD | 22.0 (454/2065) | 21.7 (404/1862) | 24.6 (50/203) | 0.328 |

| Previous ECG | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 25.4 (512/2013) | 25.3 (460/1817) | 26.5 (52/196) | 0.928 |

| Pacemaker/CRT | 7.1 (142/2013) | 7.0 (128/1817) | 7.1 (14/196) | |

| Clinical status | ||||

| Class I-II | 31.9 (631/1981) | 32.7 (581/1778) | 24.6 (50/203) | 0.043 |

| Class III-IV | 68.1 (1350/1981) | 67.3 (1197/1778) | 75.4 (153/203) | |

| EuroS-II | 4.3 (2.5-7.1) | 4.3 (2.5-7.0) | 4.8 (2.9-7.9) | 0.058 |

| STS mortality | 4.7 (3.0-7.1) | 4.7 (3.0-7.1) | 4.4 (2.9-6.9) | 0.475 |

| Baseline echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF<50% | 27.8 (538/1934) | 27.3 (474/1736) | 32.3 (64/198) | 0.154 |

| Mean baseline gradient, mmHg | 49.4±16.1 | 49.6±16.3 | 48.6±14.8 | 0.461 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.64±.0.20 | 0.64±0.21 | 0.66±0.21 | 0.101 |

| TAVI indication | ||||

| AS | 93.2 (2190/2347) | 93.5 (1993/2131) | 91.6 (196/214) | 0.133 |

| Aortic disease | 2.3 (53/2347) | 2.1 (44/2131) | 4.2 (9/214) | |

| Prosthesis dysfunction | 4.4 (104/2347) | 4.4 (94/2131) | 4.2 (9/214) | |

| Surgical risk | ||||

| High risk | 49.7 (1167/2346) | 50.3 (1072/2131) | 44.4 (95/214) | <0.001 |

| Surgical contraindicationb | 22.0 (517/2346) | 20.6 (439/2131) | 36.4 (78/214) | |

| Other non-specified | 28.3 (664/2346) | 29.1 (620/2131) | 19.1 (41/214) | |

| Bridge balloon aortic valvuloplasty | 2.9 (57/1946) | 2.7 (48/1749) | 4.6 (9/196) | 0.174 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive lung disease; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; EuroS-II: EuroScore II; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; non-TF: non- transfemoral; PAD: peripheral artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgery; TF: transfemoral; TA: transapical.

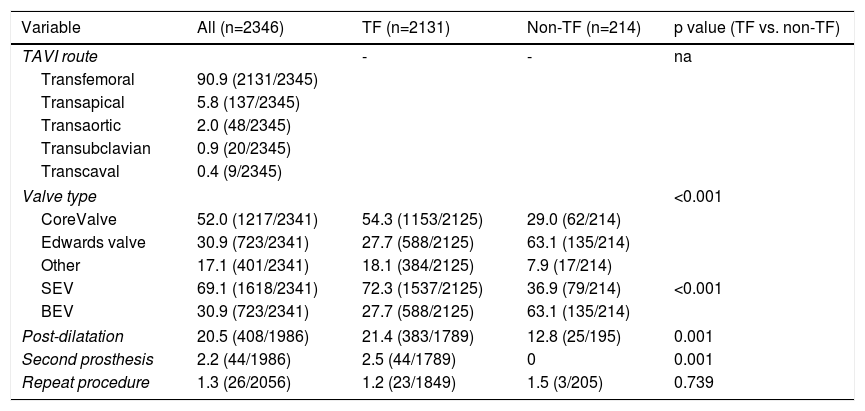

Procedural characteristics of the study population and according to the access route.

| Variable | All (n=2346) | TF (n=2131) | Non-TF (n=214) | p value (TF vs. non-TF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVI route | - | - | na | |

| Transfemoral | 90.9 (2131/2345) | |||

| Transapical | 5.8 (137/2345) | |||

| Transaortic | 2.0 (48/2345) | |||

| Transubclavian | 0.9 (20/2345) | |||

| Transcaval | 0.4 (9/2345) | |||

| Valve type | <0.001 | |||

| CoreValve | 52.0 (1217/2341) | 54.3 (1153/2125) | 29.0 (62/214) | |

| Edwards valve | 30.9 (723/2341) | 27.7 (588/2125) | 63.1 (135/214) | |

| Other | 17.1 (401/2341) | 18.1 (384/2125) | 7.9 (17/214) | |

| SEV | 69.1 (1618/2341) | 72.3 (1537/2125) | 36.9 (79/214) | <0.001 |

| BEV | 30.9 (723/2341) | 27.7 (588/2125) | 63.1 (135/214) | |

| Post-dilatation | 20.5 (408/1986) | 21.4 (383/1789) | 12.8 (25/195) | 0.001 |

| Second prosthesis | 2.2 (44/1986) | 2.5 (44/1789) | 0 | 0.001 |

| Repeat procedure | 1.3 (26/2056) | 1.2 (23/1849) | 1.5 (3/205) | 0.739 |

BEV: balloon-expandable valve; SEV: self-expandable valve; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TF: transfemoral.

Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Transapical access was the most used non-transfemoral (non-TF) route (64%, 137/214). Patients who were underwent to non-TF prosthesis implantation (9.1%) were significantly younger (non-TF 79±7 vs. TF 81±7 years, p<0.001), had a lower prevalence of females (non-TF 40.6% vs. TF 54.5%, p=0.001) and showed a higher prevalence of PAD and coronary artery disease (CAD), including more patients that had previously undergone surgical coronary revascularization. As expected, this group tended to have a higher surgical risk profile, with an EuroS-II of 4.8% (IQR 2.9-7.9) (vs. TF 4.3 [IQR 3.2-8.6], p=0.058), which was clearly significant when considering only transapical access route patients (TA 5.2% [3.2-8.6], p=0.012). Half of the global cohort was considered by the heart team as presenting high surgical risk (49.7%). In the non-TF group, when compared with the TF group, a significantly higher proportion presented a surgical contraindication supporting the decision (non-TF 36.4% vs. TF 20.6%, p<0.001). In this particular group, as expected, BEVs were more frequently implanted (BEV 63.1% vs. SEV 36.9%), and less post-dilatation was used (non-TF 12.8% vs. TF 21.4%, p=0.001). There was also less of a need for a second prosthesis during an index procedure (non-TF 0 vs. TF 2.5%, p=0.001).

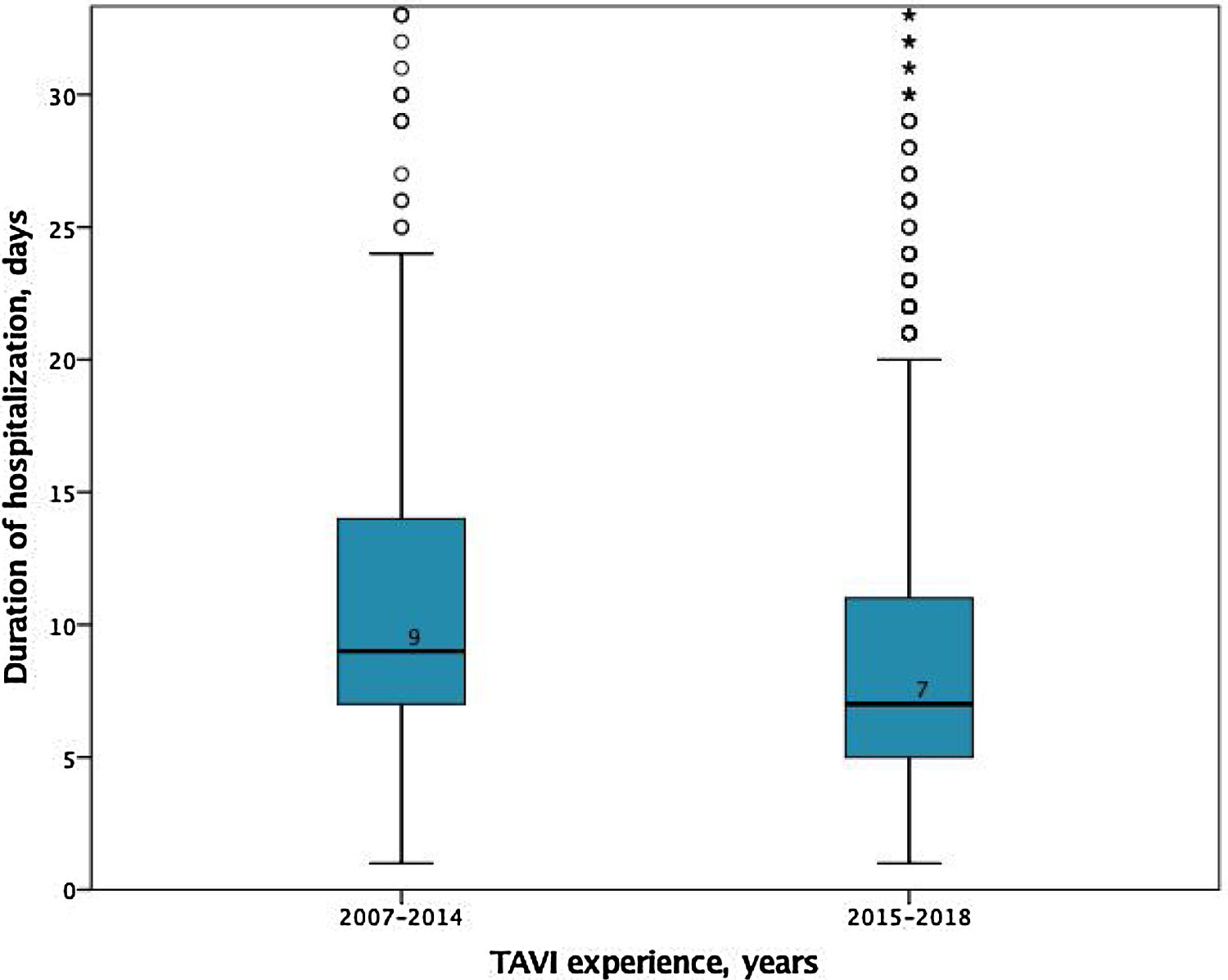

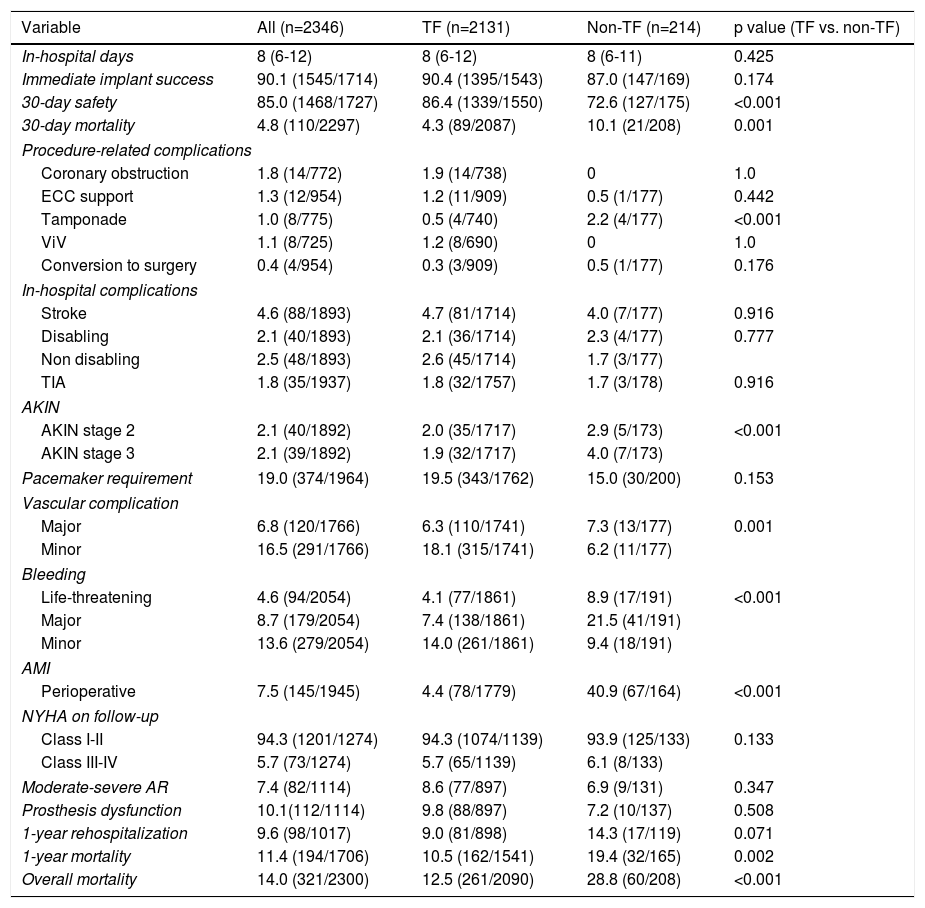

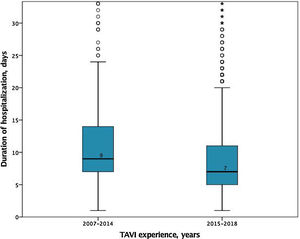

In-hospital and 30-days resultsIn-hospital results are shown in Table 3. The median duration of hospitalization decreased over the years (2007-2014 median 9 [IQR 7-14] vs. 2015-2018 median 7 days [IQR 5-11], p<0.001); Figure 2), without significant differences according to the selected route.

In-hospital and follow-up results of the study population and according to the access route.

| Variable | All (n=2346) | TF (n=2131) | Non-TF (n=214) | p value (TF vs. non-TF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital days | 8 (6-12) | 8 (6-12) | 8 (6-11) | 0.425 |

| Immediate implant success | 90.1 (1545/1714) | 90.4 (1395/1543) | 87.0 (147/169) | 0.174 |

| 30-day safety | 85.0 (1468/1727) | 86.4 (1339/1550) | 72.6 (127/175) | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 4.8 (110/2297) | 4.3 (89/2087) | 10.1 (21/208) | 0.001 |

| Procedure-related complications | ||||

| Coronary obstruction | 1.8 (14/772) | 1.9 (14/738) | 0 | 1.0 |

| ECC support | 1.3 (12/954) | 1.2 (11/909) | 0.5 (1/177) | 0.442 |

| Tamponade | 1.0 (8/775) | 0.5 (4/740) | 2.2 (4/177) | <0.001 |

| ViV | 1.1 (8/725) | 1.2 (8/690) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Conversion to surgery | 0.4 (4/954) | 0.3 (3/909) | 0.5 (1/177) | 0.176 |

| In-hospital complications | ||||

| Stroke | 4.6 (88/1893) | 4.7 (81/1714) | 4.0 (7/177) | 0.916 |

| Disabling | 2.1 (40/1893) | 2.1 (36/1714) | 2.3 (4/177) | 0.777 |

| Non disabling | 2.5 (48/1893) | 2.6 (45/1714) | 1.7 (3/177) | |

| TIA | 1.8 (35/1937) | 1.8 (32/1757) | 1.7 (3/178) | 0.916 |

| AKIN | ||||

| AKIN stage 2 | 2.1 (40/1892) | 2.0 (35/1717) | 2.9 (5/173) | <0.001 |

| AKIN stage 3 | 2.1 (39/1892) | 1.9 (32/1717) | 4.0 (7/173) | |

| Pacemaker requirement | 19.0 (374/1964) | 19.5 (343/1762) | 15.0 (30/200) | 0.153 |

| Vascular complication | ||||

| Major | 6.8 (120/1766) | 6.3 (110/1741) | 7.3 (13/177) | 0.001 |

| Minor | 16.5 (291/1766) | 18.1 (315/1741) | 6.2 (11/177) | |

| Bleeding | ||||

| Life-threatening | 4.6 (94/2054) | 4.1 (77/1861) | 8.9 (17/191) | <0.001 |

| Major | 8.7 (179/2054) | 7.4 (138/1861) | 21.5 (41/191) | |

| Minor | 13.6 (279/2054) | 14.0 (261/1861) | 9.4 (18/191) | |

| AMI | ||||

| Perioperative | 7.5 (145/1945) | 4.4 (78/1779) | 40.9 (67/164) | <0.001 |

| NYHA on follow-up | ||||

| Class I-II | 94.3 (1201/1274) | 94.3 (1074/1139) | 93.9 (125/133) | 0.133 |

| Class III-IV | 5.7 (73/1274) | 5.7 (65/1139) | 6.1 (8/133) | |

| Moderate-severe AR | 7.4 (82/1114) | 8.6 (77/897) | 6.9 (9/131) | 0.347 |

| Prosthesis dysfunction | 10.1(112/1114) | 9.8 (88/897) | 7.2 (10/137) | 0.508 |

| 1-year rehospitalization | 9.6 (98/1017) | 9.0 (81/898) | 14.3 (17/119) | 0.071 |

| 1-year mortality | 11.4 (194/1706) | 10.5 (162/1541) | 19.4 (32/165) | 0.002 |

| Overall mortality | 14.0 (321/2300) | 12.5 (261/2090) | 28.8 (60/208) | <0.001 |

AKIN: acute kidney injury; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; AR: aortic regurgitation; ECC: extracorporeal circulation; NYHA: New York Heart Association; TIA: transient ischemic attack; ViV: valve-in-valve.

Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Based on the VARC-2 criteria, the immediate implant success was globally high (90.1%), with numerically better results for TF compared to a non-TF approach, although the difference was not significant (TF 90.4% vs. non-TF 87.0%, p=0.174). There was a low rate of procedure-related complications in both access route approaches. TF patients had a lower prevalence of cardiac tamponade (TF 0.5% vs. non-TF 2.2%, p<0.001), perioperative myocardial infarction (TF 4.4% vs. non-TF 40.9%, p<0.001) and Acute Kidney Injury Network stage 2 or 3 (TF 3.9% vs. non-TF 6.9% vs. p<0.001). A non-TF approach, particularly transapical and transaortic, was associated with a higher occurrence of life-threatening and major bleeding, and also major vascular complications (non-TF 7.3% vs. TF 6.3%, p=0.001). Stroke occurred in 4.6% of our cohort, mainly non-disabling (55%, 48/88), and the prevalence of TIA was very low (1.8%).

Globally, moderate or severe aortic valve regurgitation occurred in 7.4% of patients, without significant differences between both approaches. Overall, 19.0% of patients required a definitive pacemaker during follow-up, with a numerically lower rate in the non-TF group (non-TF 15.0% vs. TF 19.5%, p=0.153).

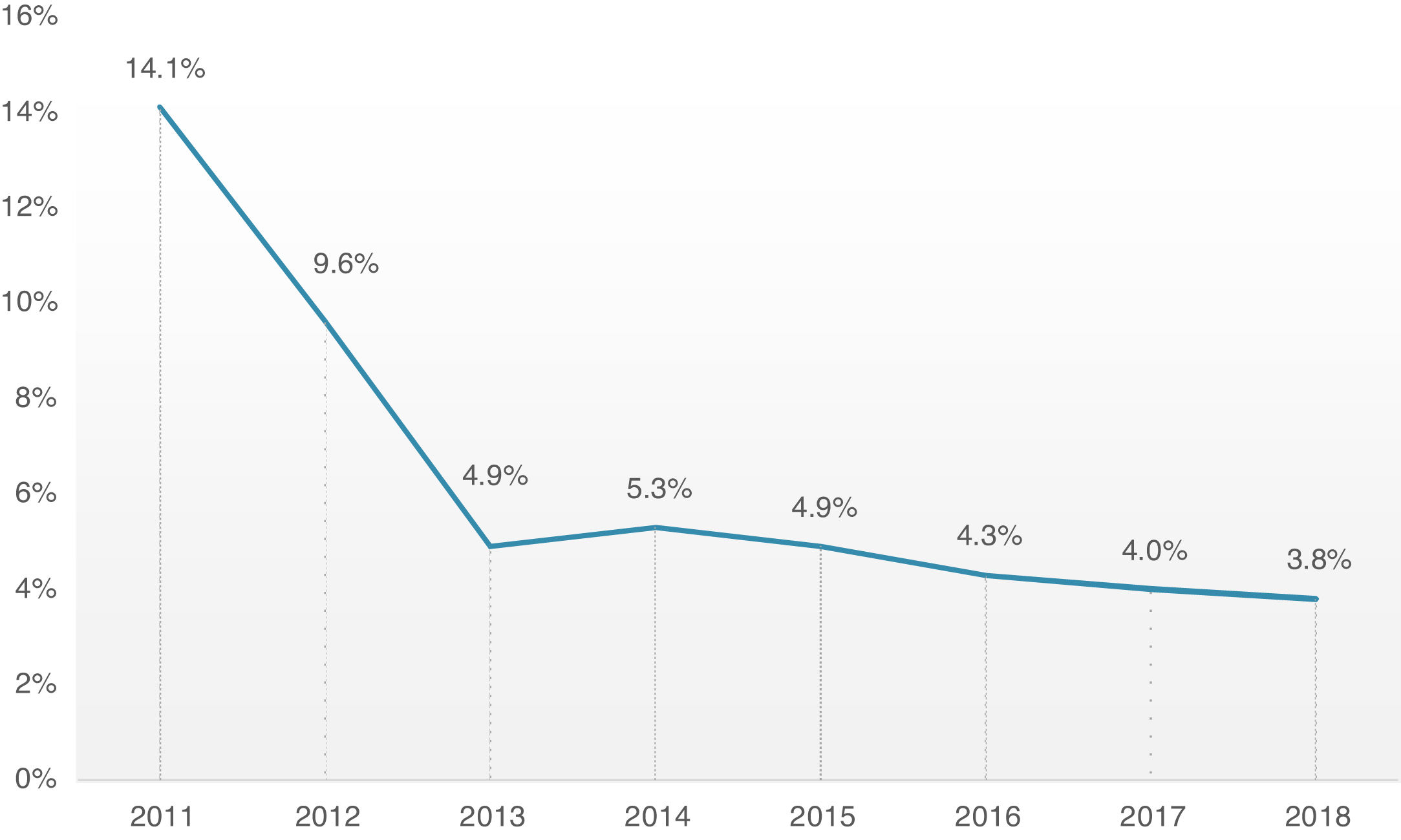

Overall, 30-day mortality was 4.8%, and the combined safety endpoint occurred in 85.0% of patients. Both endpoints were significantly better for the TF group, with a lower 30-day mortality rate (TF 4.3% vs. non-TF 10.1%, p=0.001) and higher 30-day safety endpoint (TF 86.4% vs. non-TF 72.6%, p<0.001). It is interesting to note the timeline stratification curve effect in Figure 3, showing the evolution of 30-day mortality incidence, with a significant reduction since 2011, from 14.1% to less than 4% in more recent years.

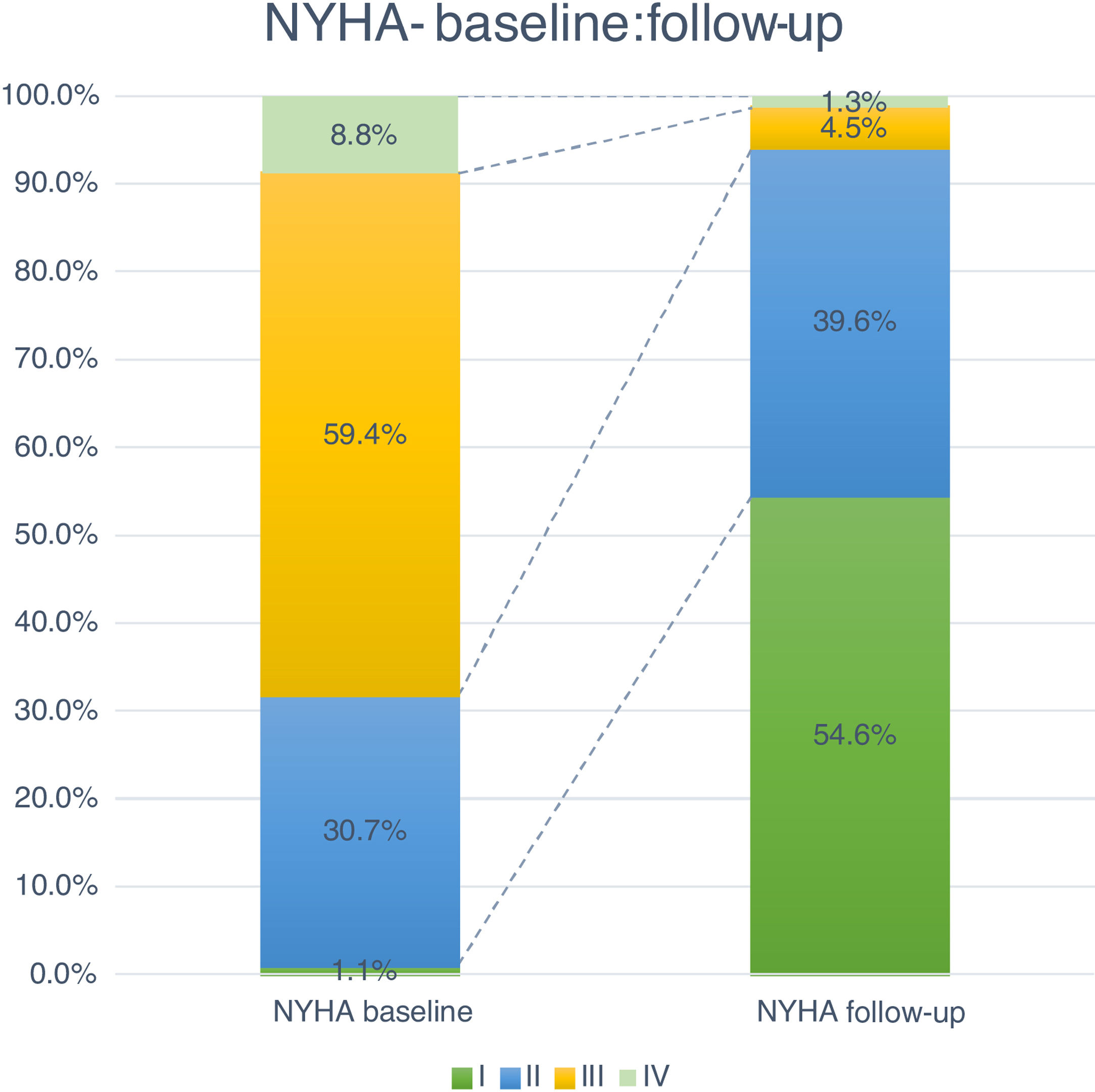

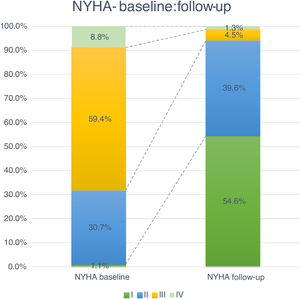

Follow-up and mortalityThe median clinical follow-up duration was 259 (IQR 96-616) days, with an accumulated mortality rate of 14.0%. During the first year of follow-up, all-cause mortality rate was 11.4%, and was significantly lower for TF patients (TF 10.5% vs. non-TF 19.4%, p=0.002). Clinically, the majority of patients improved their functional capacity, with a reduction in the percentage of patients in NYHA class III and IV of 59.4% and 8.8% at baseline to 4.5% and 1.3% at follow-up, respectively (p<0.05) (Figure 4).

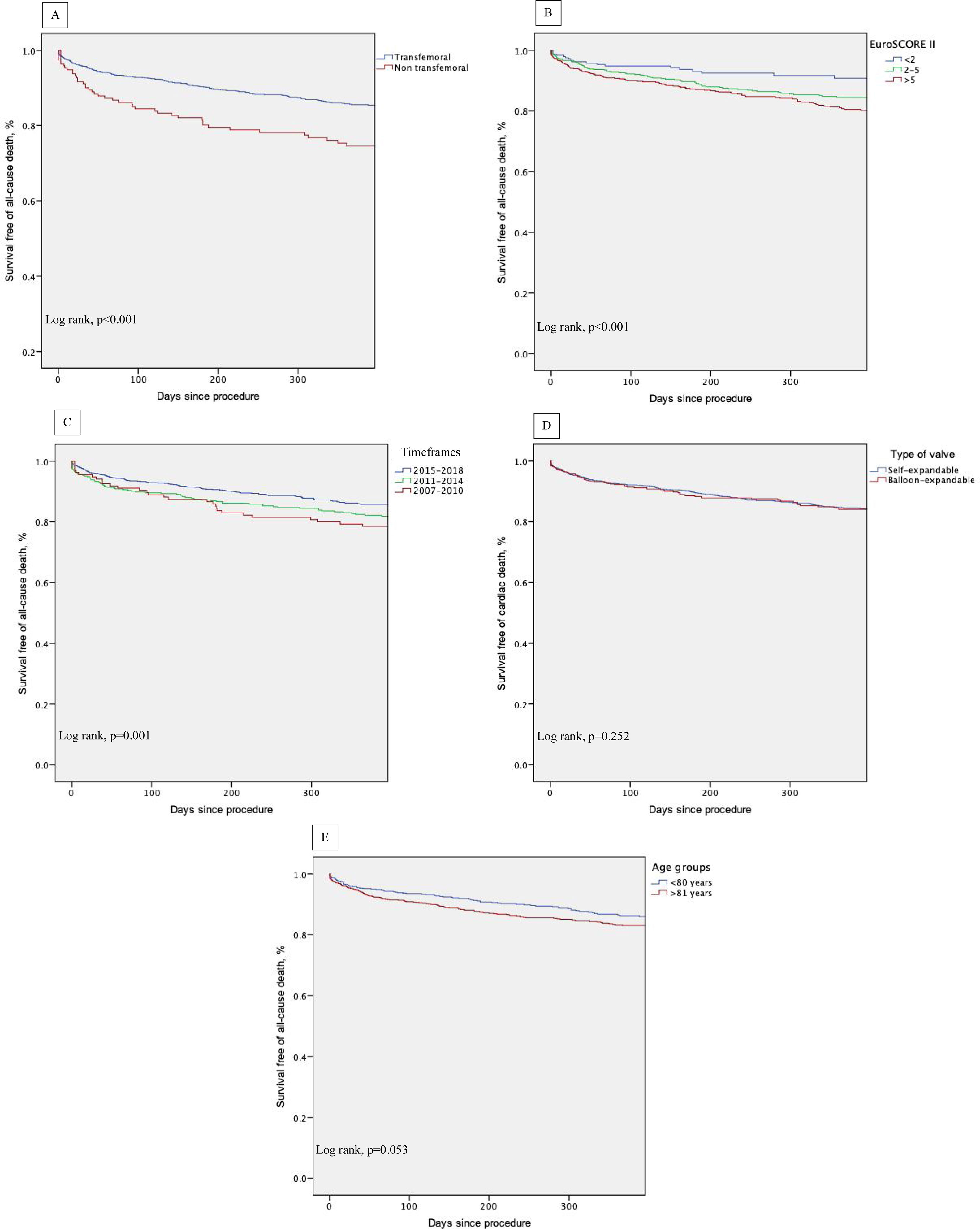

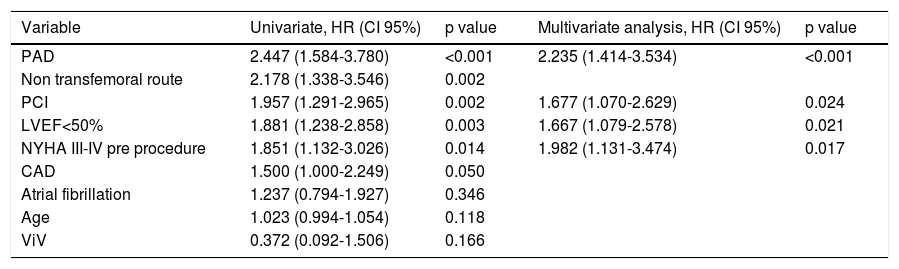

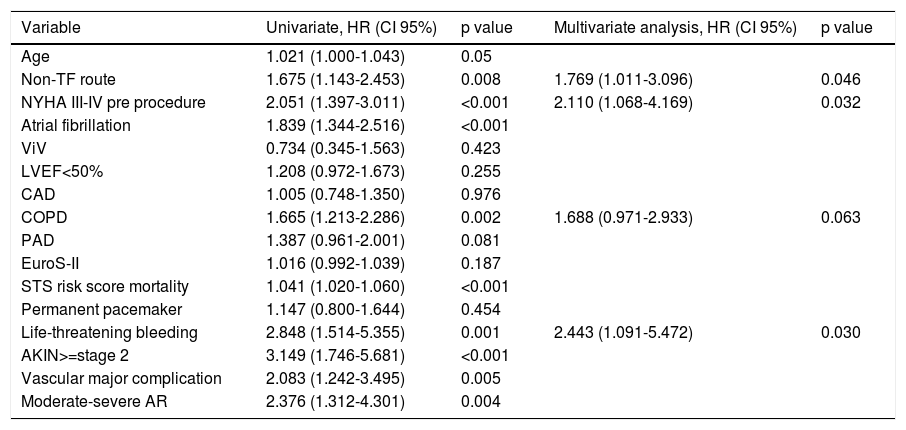

Thirty-day and one-year predictors of mortalityFollowing adjustments for gender, age, previous medical history, surgical risk scores and type of valve, the independent predictors of 30-day all-cause mortality were PAD (HR 2.24, CI 95% 1.41-3.53, p<0.001), previous PCI (HR 1.68, CI 95% 1.07-2.63, p=0.024), LV dysfunction (LVEF<50%: HR 1.67, CI 95% 1.07-2.63, p=0.021) and a worse functional status at baseline (NYHA class III-IV: HR 1.98, 95% CI 1.13-3.47, p=0.017) (Table 4). At one-year follow-up, as shown in Table 5, predictors of mortality were NYHA class III-IV (HR 2.11, 95% CI 1.06-4.16), non-transfemoral route (HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.01-3.09, p=0.046), occurrence of life-threatening bleeding (HR 2.44, 95% CI 1.09-5.47, p=0.030). There was also a trend with regard to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR 1.68, CI 95% 0.97-2.93, p=0.063). Valve type did not influence mortality.

Predictors of 30-day mortality.

| Variable | Univariate, HR (CI 95%) | p value | Multivariate analysis, HR (CI 95%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAD | 2.447 (1.584-3.780) | <0.001 | 2.235 (1.414-3.534) | <0.001 |

| Non transfemoral route | 2.178 (1.338-3.546) | 0.002 | ||

| PCI | 1.957 (1.291-2.965) | 0.002 | 1.677 (1.070-2.629) | 0.024 |

| LVEF<50% | 1.881 (1.238-2.858) | 0.003 | 1.667 (1.079-2.578) | 0.021 |

| NYHA III-IV pre procedure | 1.851 (1.132-3.026) | 0.014 | 1.982 (1.131-3.474) | 0.017 |

| CAD | 1.500 (1.000-2.249) | 0.050 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.237 (0.794-1.927) | 0.346 | ||

| Age | 1.023 (0.994-1.054) | 0.118 | ||

| ViV | 0.372 (0.092-1.506) | 0.166 |

Other adjusted variables: Aortic valve area, mean gradient, coronary artery bypass graft, chronic obstructive lung disease, chronic kidney disease, EuroS-II, Society of Thoracic Surgery mortality risk score, type of valve (self-expandable valve and balloon-expandable valve), size of prosthesis, permanent pacemaker need, moderate or severe paravalvular aortic leak.

Abbreviations: CAD: coronary artery disease; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PAD: peripheral artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; ViV: valve-in-valve.

Predictors of 1-year mortality.

| Variable | Univariate, HR (CI 95%) | p value | Multivariate analysis, HR (CI 95%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.021 (1.000-1.043) | 0.05 | ||

| Non-TF route | 1.675 (1.143-2.453) | 0.008 | 1.769 (1.011-3.096) | 0.046 |

| NYHA III-IV pre procedure | 2.051 (1.397-3.011) | <0.001 | 2.110 (1.068-4.169) | 0.032 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.839 (1.344-2.516) | <0.001 | ||

| ViV | 0.734 (0.345-1.563) | 0.423 | ||

| LVEF<50% | 1.208 (0.972-1.673) | 0.255 | ||

| CAD | 1.005 (0.748-1.350) | 0.976 | ||

| COPD | 1.665 (1.213-2.286) | 0.002 | 1.688 (0.971-2.933) | 0.063 |

| PAD | 1.387 (0.961-2.001) | 0.081 | ||

| EuroS-II | 1.016 (0.992-1.039) | 0.187 | ||

| STS risk score mortality | 1.041 (1.020-1.060) | <0.001 | ||

| Permanent pacemaker | 1.147 (0.800-1.644) | 0.454 | ||

| Life-threatening bleeding | 2.848 (1.514-5.355) | 0.001 | 2.443 (1.091-5.472) | 0.030 |

| AKIN>=stage 2 | 3.149 (1.746-5.681) | <0.001 | ||

| Vascular major complication | 2.083 (1.242-3.495) | 0.005 | ||

| Moderate-severe AR | 2.376 (1.312-4.301) | 0.004 |

Other adjusted variables: Aortic valve area, mean gradient, coronary artery bypass graft, chronic obstructive lung disease, chronic kidney disease, EuroS-II, Society of Thoracic Surgery mortality risk score, type of valve (self-expandable valve and balloon-expandable valve), size of prosthesis, permanent pacemaker need, moderate or severe paravalvular aortic leak.

Abbreviations: AKIN: Acute Kidney Injury Network; AR: aortic regurgitation; CAD: coronary artery disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EuroS-II: EuroScore II; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; Non-TF: non-transfemoral; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PAD: peripheral artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the first year of follow-up also shows decreased survival of patients who underwent non-transfemoral TAVI (log-rank p<0.001) and those with higher surgical risk (EuroS-II>5%) (log-rank p<0.001). There was also a trend of decreased survival in older patients (log-rank p=0.053) (Figure 5, A-E).

DiscussionSince its introduction in Portugal in 2007, the number of TAVI procedures has grown exponentially,18 similar to the pattern seen following the adoption of this technology in Western countries.23

Improved survival rates after TAVI, with a significant decrease in periprocedural mortality, reflect innovative device technology, but also the increased use of transfemoral TAVI, learning curves and optimized patient selection.24 The increasing availability of smaller delivery systems and operator experience have brought about an increase in the number of patients treated with a TF approach, and approximately 90% of our patients were effectively treated using TF access, a percentage slightly above the 80% reported in FRANCE TAVI, with a corresponding decline in transapical access.25 The predominant use of SEV in our registry may have, on the one hand, been influenced by the steady rise in TF TAVI, and on the other according to their availability in Portugal. As expected, balloon-expandable valves (BEV) were the main valve system used in TA TAVI. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy to mention that currently there is not enough evidence to claim the superiority of one device over the other.26 Valve selection should be tailored according to the patient's clinical and anatomical characteristics, which is standard of practice at the different Portuguese TAVI centers.

Evidence showing that ViV procedures for prosthesis dysfunction have favorable outcomes14 also contributed to the increasing number of these procedures in Portugal.

Approximately 50% of patients were considered high risk for surgery following a heart team assessment. This was not exclusively defined according to conventional surgical risk scores, in fact, in our cohort the mean EuroS-II was in the intermediate strata. Other factors, such as advanced age, associated comorbidities and frailty were determining factors, although the latter has not yet been fully reflected in the registry. Evidence shows that decision making in valvular heart disease involves a complex algorithm to define the risk-benefit ratio. Currently there is no single validated specific TAVI risk score, suggesting that the best approach should be based on the combination of the existing surgical scores together with frailty parameters and the presence of specific organ failure. The main goal should be to avoid TAVI futility.21,22

Our analysis revealed an incidence of stroke after TAVI of 4.6%, of which almost half were disabling. Although this result is below the incidence of stroke reported in the PARTNER cohorts A and B (5.5 and 6.7% respectively),27,28 and similar to the incidence of peri-operative stroke following surgical AVR in elderly patients, which ranges from 3 to 7%,29 this is still a matter of concern and an area of improvement that needs to be addressed. Embolic protection devices (EPD) are not used by default at Portuguese TAVI centers, however, so far, although published results show that EPD may help reduce the volume and size of periprocedural silent ischemic brain lesions identified on MRI, it did not reduce the incidence of new lesions and clinically significant neurological events.30,31The clinical impact of EPD needs further investigation in randomized trials prior to its widespread use.

The pacemaker implantation rate in our registry was 19% in the overall cohort, with a significant difference between TF 19,5% and TA 10.7% approach. This attributed to the differences between the predominant prosthesis type used in each of the access routes cohorts, SEV and BEV, respectively. A recent meta-analysis of different registries showed pacemakers were a requirement in 8% of Sapien TFs and 22% for CoreValve,15 in line with our data, but higher than those reported in the PARTNER trials, probably because of the higher anatomic complexity of real-world patients.

Our registry reported an overall 7.4% incidence of moderate paravalvular leak (>=2), which is similar to other European registries and explained by the operator learning curves, standardization of techniques and new generation devices with extended sealing skirts.32

Concerning hard outcomes, in the PARTNER study, mortality was 3.4 and 5% in cohorts A and B, respectively.6,33 Different registries present wide variability in mortality ranging from 5.4 to 12.4%, however, they compare different patients risk profiles, types of prosthesis and access routes.29,34–36 In our global cohort, 30-day mortality has been decreasing since the beginning of the TAVI program, from 14.1% in 2011 to approximately 4% in the last 3 years, which is in line or slightly below other reported registries.14,25 It is probably attributable to the fact that although our cohort had an advanced mean age of 81 years, the mean risk profile was intermediate. There is, in fact, a growing body of evidence that supports the extension of TAVI to increasingly lower risk patients, consistently demonstrating its noninferiority in comparison with conventional surgery.8,11 It is also important to highlight that the low mortality of our cohort evidences that most of the fatalities were unrelated to periprocedural complications, which had low prevalence. A major conclusion from these data is that our focus should be on better prediction of risks and benefits of the procedure and appropriate patient selection.

Regarding the non-TF approach, and particularly the TA, when comparing with TF route, the former was associated with a lower 30-day safety composite outcome and higher mortality in our registry, similar to what has been reported in other studies.33,37–39 The explanation is multifactorial, but clearly TA patients had increased prevalence of significant co-morbidities and a higher risk profile. A significant contribution might be derived from the increased rate of procedural complications, such as life-threatening and major bleeding, perioperative myocardial infarction and cardiac tamponade.

Based on VARC 2 criteria, the predictors for 30-day all-cause mortality were PAD, significant CAD with previous PCI, depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and an advanced heart failure (HF) clinical status. Buellesfeld et al. showed the patient's baseline functional state to be an independent predictor of hospital mortality40 and the Italian registry indicated that an ejection fraction under 40%, diabetes, prior valvuloplasty and procedure-related complications were associated with worse short term prognosis.29 The Ibero-American registry also underlined the importance of post-TAVI complications and logistic EuroS-II as predictors of mortality at 30 days.16 Also, in a recent meta-analysis stage>=2 AKI was a strong predictor for 30-day mortality, although interestingly many patients saw an improvement in renal function after TAVI rather than kidney injury due to renal decongestion and increased perfusion. Preprocedural pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels were also a strong predictor of 30-day and midterm mortality. This is believed to be related to advanced HF with systolic and diastolic dysfunction. Likewise, baseline clinical status, represented by prior hospitalizations and preprocedural LVEF<=30%, had a significant impact on short term mortality.41

As independent predictors of one-year all-cause mortality we identified patient characteristics before the procedure, such as pre-procedural NYHA class III/IV and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and procedural factors such as the non-NF access route, which may be a surrogate for significant PAD. These results are corroborated by other registries and trials, showing also that some comorbidities are related to worse long-term prognosis, such as advanced age,17 frailty,35 male gender, end-stage renal disease,34 porcelain aorta,35 low gradient aortic stenosis,42 reduced LVEF,17 NYHA class,36 mitral insufficiency grade>=2+,42 residual postintervention aortic regurgitation,6 intraprocedural conversion to surgery, peri-intervention stroke,39 or postintervention pulmonary embolism.42

In our registry there was a sub-optimal percentage of patients lost to follow-up at one-year (22%), although acceptable when compared to other observational studies.43,44,45 This can be explained by the nature of this prospective nationwide real-world registry that involves participating centers with various differences relating to the volume of procedures, follow-up approach and data registration. Also, compared to other European countries, the small number of 0.346 to 0.7 TAVI centers per million inhabitants in the registry history, can limit patient accessibility to those hospital centers because of distance, which is a known predictor of loss to follow-up.47 It is worth mentioning that an automatic registration of a patient's vital status in the RNCI-VaP could be an effective way of strengthening the quality and completeness of data in the future.

Despite the acknowledged potential bias, the findings from this landmark study should help us to select appropriate candidates for TAVI accurately, with the main goal of referring patients in whom treatment benefit outweighs the risk, thus improving clinical benefit and avoiding futility. Nevertheless, a balance needs to be achieved because even in high risk patients with several comorbidities, health- related improvements in quality of life and reduced congestive HF hospitalizations should be taken in account.

Study limitationsThe data from the RNCI-VaP registry is self-reported and consequently subject to inclusion bias. Nevertheless, this registry is representative of the current standards of practice in Portugal, because it obtained data on 96.5% of the total number of implanted valves.

For some relevant variables we could not obtain data from all patients, which is a limitation inherent to the characteristics of a national registry that depends on the voluntary participation of the investigators, potentially causing selection bias. Events were reported by the investigators and were not independently reviewed, so we cannot rule out the possibility of under or over reporting of events. Also, the RNCI-VaP does not currently have either internal or external auditing. As such, definitive conclusions regarding cause and effect cannot be drawn from this study.

Although we acknowledge these limitations, the investigators of the RNCI-VaP consider this registry to be essential to ensure the safe and successful clinical applicability of the constantly evolving transcatheter aortic valve technology in Portugal. This paper includes the first published data on patients treated with TAVI in Portugal. It is noteworthy that the success and complication rates were similar to those reported by other European countries’ registries.32

ConclusionsThe RNCI-VaP shows that TAVI has been implemented with great success in Portugal. In this real-world all-comers all-centers registry of patients who underwent TAVI (both conventional and ViV), the procedure was safe and effective. Characteristics related to the access route, patient comorbidities and baseline clinical status adversely affected long-term prognosis and should therefore be taken in consideration when selecting patients for the procedure.

The systematic assessment and reporting of patients who underwent TAVI in Portugal is of paramount importance, eliciting a pragmatic assessment of TAVI results in the different centers and stimulating scientific multicentric production.

Author contributionsCG, PCF and RCT: study concept, design and drafting of the manuscript; CG, PCF, SM, RCT: analysis and interpretation of data; PB, PCS, LP, JCS, JB, MA, VGR, BS, JB, EIO, DC, JS: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Disclosure statementThe authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.