The prevention of coronary artery disease (CAD) is a critical focus area in cardiology. As per the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice,1 the current definition of prevention is a binary variable. It categorizes individuals into two groups: those aiming to prevent their first myocardial infarction (MI) (primary prevention), and those who have already experienced a MI and are now aiming to prevent a second one (secondary prevention).

However, certain healthcare experts in disease prevention2,3 argue that this classification of cardiovascular prevention as solely primary and secondary is overly simplistic. They believe that this approach fails to capture the true complexity of the subject, with significant implications in terms of how cardiologists diagnose and treat CAD.

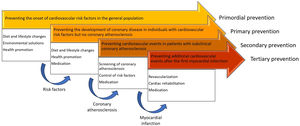

Instead, a more comprehensive classification system can be employed to describe cardiovascular prevention. This system involves four distinct categories3: primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention (Figure 1).

Primordial prevention is a vital component of cardiovascular disease prevention as it aims to halt the development of cardiovascular risk factors in the general population. The strategies employed in primordial prevention encompass multifaceted approaches such as advocating for a healthy diet, promoting lifestyle modifications such as regular exercise, discouraging smoking, and reducing harmful environmental exposure.2

Primary prevention is centered around individuals who have cardiovascular risk factors but have not yet manifested any evidence of CAD or in whom CAD has not been diagnosed. Similarly to primordial prevention, primary prevention strategies prioritize lifestyle modifications and dietary adjustments to manage risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity and diabetes. These lifestyle changes include adopting a healthy diet, engaging in regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and managing stress. In addition, pharmacological interventions, such as statins or antihypertensive drugs, could be prescribed, tailored to the individual's specific risk profile. By combining lifestyle modifications with appropriate medication, the primary prevention approach aims to significantly reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events in individuals at risk.2

Secondary prevention concentrates on diagnosing subclinical asymptomatic CAD. The objective of secondary prevention is to identify individuals at high risk for cardiovascular events through screening methods, which enable the early detection of subclinical CAD. Once this is diagnosed, prompt intervention and implementation of appropriate strategies become crucial in controlling cardiovascular risk factors and minimizing the progression of the disease. Management strategies in secondary prevention encompass lifestyle modifications, similar to primary prevention. Medications are often prescribed to manage specific risk factors, including antiplatelet agents. While their utility in primary prevention is limited,4,5 more substantial evidence supports their effectiveness in secondary prevention.6 Close monitoring of the patient's condition and more regular follow-up visits enable healthcare providers to adjust interventions and optimize risk factor control, thus reducing the likelihood of future cardiovascular events.2

Tertiary prevention focuses on preventing additional cardiovascular events after the occurrence of an initial event. This stage emphasizes comprehensive strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality associated with CAD. It involves a combination of approaches, including coronary revascularization procedures such as angioplasty or bypass surgery; cardiac rehabilitation programs, providing structured exercise training, education, and support to enhance cardiovascular health; and medications, including antiplatelet agents, statins, beta-blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, to prevent recurrent events and maintain optimal cardiovascular function. Tertiary prevention ensures that individuals who have experienced a cardiovascular event receive appropriate interventions and support to minimize the risk of future events and achieve the best possible outcomes.2

By adopting this enhanced approach, healthcare professionals, including cardiologists, can better understand and address the multifaceted nature of CAD prevention.

In light of this classification of preventive cardiology, how can we improve patient care and decrease the prevalence of patients in tertiary prevention?

Regarding primary prevention, evidence suggests that patients’ cardiovascular risk factors are not adequately controlled. The primary care arm of EUROASPIRE V7 assessed 2759 individuals (57.6% women, mean age 59 years) without previous manifestations of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. These individuals had been on blood pressure- or cholesterol-lowering medications for at least six months before the study interview. The findings revealed that 18% of participants were smokers, 43.5% were obese, and among those on blood pressure medications, only 47% achieved target levels of <140/90 mmHg (or <140/85 mmHg for diabetics). Furthermore, of those taking lipid-lowering agents, only 46.9% achieved low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels below 100 mg/dl. The prevalence of self-reported diabetes was 35.8%, and approximately one in three individuals had glycated hemoglobin levels of 7.0% or higher. Only 36.4% engaged in regular exercise, while nearly 40% were entirely sedentary.7 In light of these results, it is evident that greater attention and efforts are required to optimize primary prevention strategies and ensure effective control of patients’ cardiovascular risk factors.

Regarding secondary prevention, both general practitioners and cardiologists should prioritize the diagnosis of subclinical CAD as a crucial aspect of cardiovascular care, if we wish to reduce the incidence of MI, prevent sudden cardiac death, and have a meaningful effect on cardiovascular prevention. Each patient in tertiary prevention represents a missed opportunity for preventive cardiology.

The advent of cardiac computed tomography (CT) has revolutionized secondary prevention. Previously available diagnostic exams such as treadmill stress testing, stress echocardiography, and myocardial perfusion scintigraphy could only detect obstructive CAD with blood-flow limiting lesions and subsequent myocardial ischemia. However, cardiac CT has made it possible to identify non-obstructive subclinical coronary atherosclerosis.

The coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, obtained through non-contrast cardiac CT, is an affordable and non-invasive imaging technique that provides a personalized assessment of atherosclerotic burden. It reflects an individual's cumulative lifetime risk factor exposure, which cannot be easily obtained from serum markers or other cardiac imaging methods.8

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA),9 Heinz Nixdorf Recall10 and EISNER11 studies, as well as ongoing studies such as CorCal (NCT03439267) and ACCURATE (NCT03972774), are shedding light on the potential benefits of using CAC scoring as a screening tool for CAD, similar to how mammography is used for breast cancer screening.12

The MESA cohort, consisting of asymptomatic individuals without prior coronary heart disease, showed that even mild calcification (CAC score 1–100) significantly increases the risk of coronary heart disease compared to those with no calcification, with a hazard ratio of 3.61 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.9–6.7).9 Furthermore, among individuals in the MESA study with normal LDL cholesterol levels, the presence of any CAC remains strongly associated with an elevated risk of coronary heart disease events, with a hazard ratio of 6.65 (95% CI 2.99–14.78).13

A CAC scan revealing zero coronary calcification serves as a powerful negative risk factor for CAD. It effectively reclassifies a significant number of individuals from intermediate- to low-risk categories, allowing for the implementation of conservative treatment strategies.14,15 A comprehensive meta-analysis incorporating data from 13 studies and over 71595 asymptomatic subjects confirmed that individuals with a CAC score of 0 have a relative risk of 0.15 (95% CI 0.11–0.21) for suffering a cardiovascular event compared to those with any CAC.16 Additionally, in a cohort of 44052 asymptomatic patients, a CAC score of 0 was associated with less than 1% 10-year risk of all-cause mortality, indicating an excellent long-term prognosis.17 These robust findings further support the potential of the CAC score as a valuable tool in cardiovascular risk assessment across diverse patient populations, including women, diabetic patients, and the elderly.13–16

Patients who had a higher than expected CAC score and were reclassified into high- or very-high cardiovascular risk groups are more likely to adhere to statin therapy18 and antihypertensive medications.11 The visual representation of CAC scores may act as a powerful motivator for patients, increasing their perceived cardiovascular risk and encouraging them to adhere to medications and adopt healthier lifestyles.

In the early stages of CAC scoring, there were concerns regarding radiation exposure. However, with advancements in modern testing equipment, the median radiation exposure associated with CAC scoring is approximately 1 mGy.19 This level of exposure is significantly lower than the mean of 4.15 mGy to the breast from a digital mammography, as identified in the Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial conducted by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network.20

The importance of CAC scoring in secondary prevention led to the 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice1 recommending that CAC scoring may be considered to improve risk classification around treatment decision thresholds (class IIb, level of evidence B). The more recent 2022 Portuguese Society of Cardiology consensus document on chronic coronary syndrome assessment and risk stratification in Portugal6 recommends CAC scoring for every asymptomatic adult over 40 years old with moderate cardiovascular risk (SCORE ≥1%–<5%).

In conclusion, the classification of cardiovascular prevention into primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention provides a comprehensive framework for better addressing the treatment of CAD. To improve patient care and to reduce the number of patients in tertiary prevention, both optimizing the control of cardiovascular risk factors in primary prevention and diagnosing subclinical CAD in secondary prevention are crucial to reduce the burden of CAD.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.