In acute coronary syndromes (ACS), the optimal revascularization strategy for unprotected left main coronary artery (ULMCA) culprit lesion has been under-investigated. Therefore, we compared clinical characteristics and short- and medium-term outcomes of percutaneous and surgical revascularization in ACS.

Methods and resultsOf 31886 patients enrolled in a multicenter, national, prospective registry study between October 2010 and December 2020, 246 (0.8%) had ULMCA as a culprit lesion and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) alone (n=133, 54%) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) alone (n=113, 46%). Patients undergoing PCI presented more frequently ongoing chest pain (68% versus 41%, p<0.001) and cardiogenic shock (25% versus 1%, p<0.001). Time from admission to revascularization was higher in surgical group with a median time to CABG of 4.5 days compared to 0 days to PCI (p<0.001). Angiographic success rate was 93.2% in patients who underwent PCI. Primary endpoint (all-cause death, non-fatal reinfarction and/or non-fatal stroke during hospitalization) occurred in 15.9% of patients and was more frequent in the PCI group (p<0.001). After adjustment, surgical revascularization was associated with better in-hospital prognosis (odds ratio (OR) 0.164; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.04–0.64; p=0.009). Similar results were achieved after propensity score matching. No difference was found at one-year all-cause death.

ConclusionPercutaneous coronary intervention was the most common revascularization strategy in the ACS with ULMCA culprit lesion. PCI was preferred in unstable patients and presented a high angiographic success. CABG was often delayed and preferred in low-risk patients. At one-year follow-up, PCI and CABG conferred a similar prognosis. The two approaches appear complementary in this high risk cohort.

Nas síndromes coronárias agudas (SCA), a estratégia de revascularização mais adequada para o tratamento das lesões culprit do tronco comum não protegido (TCNP) tem sido subinvestigada. O objetivo deste trabalho foi comparar a revascularização cirúrgica e a revascularização percutânea neste contexto relativamente a características clínicas e outcomes a curto e médio prazo.

Métodos e resultadosDos 31 886 doentes incluídos num registo prospetivo, nacional e multicêntrico entre outubro de 2010 e dezembro de 2020, 246 (0,8%) tinham o TCNP como lesão culprit e foram submetidos a intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) isolada (n=133, 54%) ou cirurgia de revascularização miocárdica (CABG) isolada (n=113, 46%). Os doentes submetidos a ICP apresentaram mais frequentemente dor precordial mantida (68% versus 41%, p<0,001) e choque cardiogénico (25% versus 1%, p<0,001). O tempo entre a admissão e a revascularização foi superior no grupo cirúrgico com uma mediana de tempo até à CABG de 4,5 dias comparativamente com 0 dia até à ICP (p<0,001). O sucesso angiográfico foi 93,2% nos doentes submetidos a ICP. O endpoint primário (morte por todas as causas, reenfarte não fatal e/ou acidente vascular cerebral não fatal durante a hospitalização) ocorreu em 15,9% dos doentes. Após ajuste, a CABG foi associada a melhor prognóstico durante o internamento (OR 0,164; 95%CI, 0,04-0,64; p=0,009). Resultados semelhantes foram obtidos após análise por propensity-score matching. Nenhuma diferença foi encontrada na mortalidade a um ano.

ConclusãoA ICP foi o método de revascularização mais comum em doentes com SCA e lesão culprit do TCNP. A ICP foi a revascularização preferencial em doentes instáveis e apresentou elevado sucesso angiográfico. A CABG foi frequentemente atrasada e preferida em doentes de baixo risco. A um ano, ICP e CABG apresentaram prognóstico similar. Desta forma, os dois métodos de revascularização parecem complementares nesta coorte de alto risco.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the gold standard treatment of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) as studies have demonstrated a reduction in recurrence of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death.1–5 In-hospital mortality from ACS due to non-left main coronary artery (LMCA) has decreased to 3–7%.6 However, the situation is less certain for ACS from unprotected LMCA (ULMCA), both for treatment strategy and outcomes. As the LM supplies about 75% of the myocardium in a right- or co-dominant and essentially 100% in a left dominant system, flow compromise is associated with very high morbidity and mortality, resulting from pump failure and malignant ventricular arrhythmias.7–9 Randomized controlled trials to guide revascularization strategy for LMCA disease enrolled highly selected patients mainly with chronic coronary syndrome.10–19 In fact, patients presenting with ACS due to ULMCA have been under-investigated so far and no dedicated randomized trial is yet available. Registries, such as the current study, provide additional evidence. Hence, we sought to compare percutaneous and surgical revascularization in ACS patients with ULMCA culprit lesion regarding clinical characteristics and short- and medium-term outcomes.

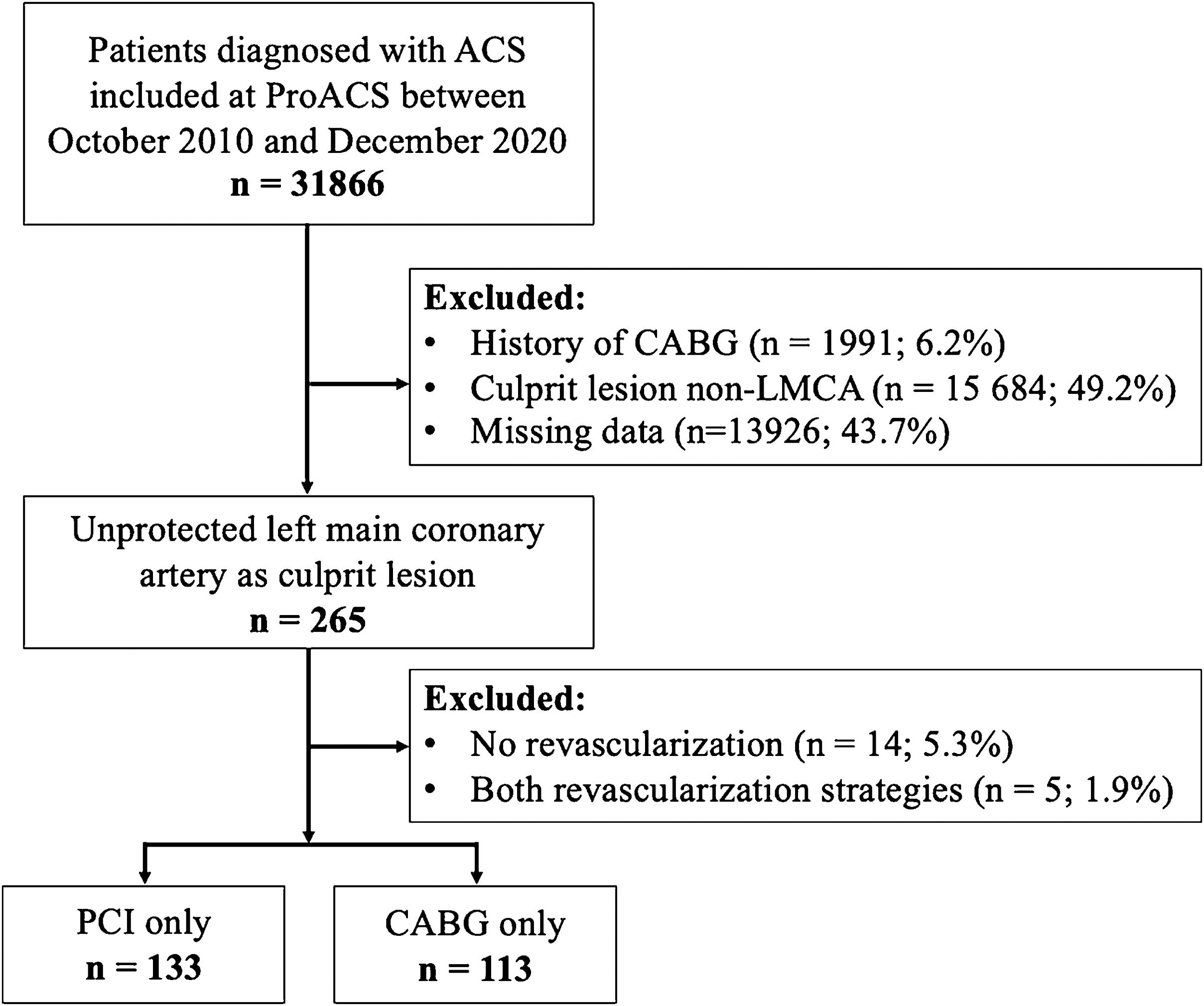

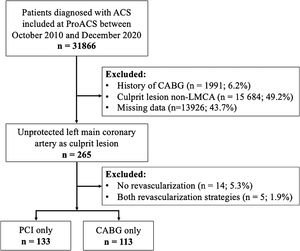

MethodsStudy design and participantsAll consecutive patients included in the Portuguese Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (ProACS) between October 2010, and December 2020, were revised. Those in which the ULMCA was considered the culprit lesion were selected and categorized according to the treatment strategy as PCI alone or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) alone. To exclude patients with protected LMCA disease, all individuals with a history of CABG were excluded. Patients with missing information on previous revascularization, culprit lesion, revascularization during the current hospitalization, those with no revascularization during hospitalization and those who underwent both types of revascularization during the index admission were also excluded.

Study setting and data sourceThe ProACS is a multicenter, continuous, prospective observational registry that is under the aegis of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology and is coordinated by the National Center for Data Collection in Cardiology. All Portuguese cardiology departments were invited to participate and consecutively include adult patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of ACS (ST-elevation MI (STEMI), non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) or unstable angina). Data collected include demographic and baseline characteristics, laboratory test results, clinical course, medical treatment, revascularization, and data at one-year follow-up. Details of the ProACS have been described in previous publications.20 The registry was approved by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority (no. 3140/2010), is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT 01642329), and is supervised by an Executive Committee appointed for this purpose. The protocol obtained ethical approval at each participant center.

Study endpointsThe primary endpoint was a composite of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE) including all-cause death, non-fatal reinfarction and/or non-fatal stroke during hospitalization. The secondary endpoint was all-cause mortality at one-year after hospital discharge. Other in-hospital outcomes included the individual components of the primary endpoint, aborted cardiac arrest, sustained ventricular tachycardia and cardiogenic shock occurrence during the hospital stay.

Study definitionsMyocardial infarction was defined as the presence of angina or equivalent at rest associated with electrocardiographic abnormalities suggestive of ischemia and elevated values of the cardiac troponin or creatine kinase MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) with at least one above the reference value and with less than 48 hours of evolution. STEMI was defined by the presence of persistent (>30 minutes), ≥1 mm ST segment elevation in at least two contiguous leads. The remaining cases were defined as non-ST segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS) including NSTEMI and unstable angina. Reinfarction was defined as the recurrence of chest pain suggestive of ischemia, after resolution of admission symptoms, lasting more than 20 minutes and accompanied by electrocardiographic changes and a new elevation of the CK-MB and/or the cardiac troponin value (>50% or >20% in relation to the previous value, respectively). Stroke was defined as the new onset of focal neurological deficits and included ischemic and hemorrhagic types. Renal insufficiency was defined as a serum creatinine level >2 mg/dL, dialysis, or kidney transplant. Angiographic success was defined as achievement of residual stenosis <30% in the presence of grade 3 thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were presented as mean±standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) and were compared between groups using independent samples t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, based on distribution. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and were compared using the chi-square or Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. The determinants of the primary endpoint were sought by multivariable logistic regression analyses using the stepwise forward method. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used for the calibration of the regression model. OR and 95% CI were calculated. Cumulative incidences of events were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference was assessed by the log rank test. Propensity score matching was performed to minimize the effect of treatment selection bias and to account for the differences in baseline, clinical and echocardiographic characteristics. A propensity score was generated for each patient in the standard fashion by performing a logistic regression for PCI versus CABG patients using the following variables: age, gender, dyslipidemia, previous history of pectoris angina, previous history of renal insufficiency, STEMI, Killip-Kimball class at admission ≥II and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <30%. Patients were matched with a propensity caliper of 0.05. All reported p values are two-tailed and values of p<0.05 indicated statistical significance. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

ResultsStudy populationOf 31886 patients diagnosed with ACS between October 2010 and December 2020, 265 (0.8%) had ULMCA as the culprit lesion according to the invasive coronary angiography. In 246 patients, revascularization was performed using PCI alone (n=133; 54.1%) or CABG alone (n=113; 45.9%), and therefore were included in the analysis and categorized according to the treatment strategy. The flow chart of the study is shown in Figure 1.

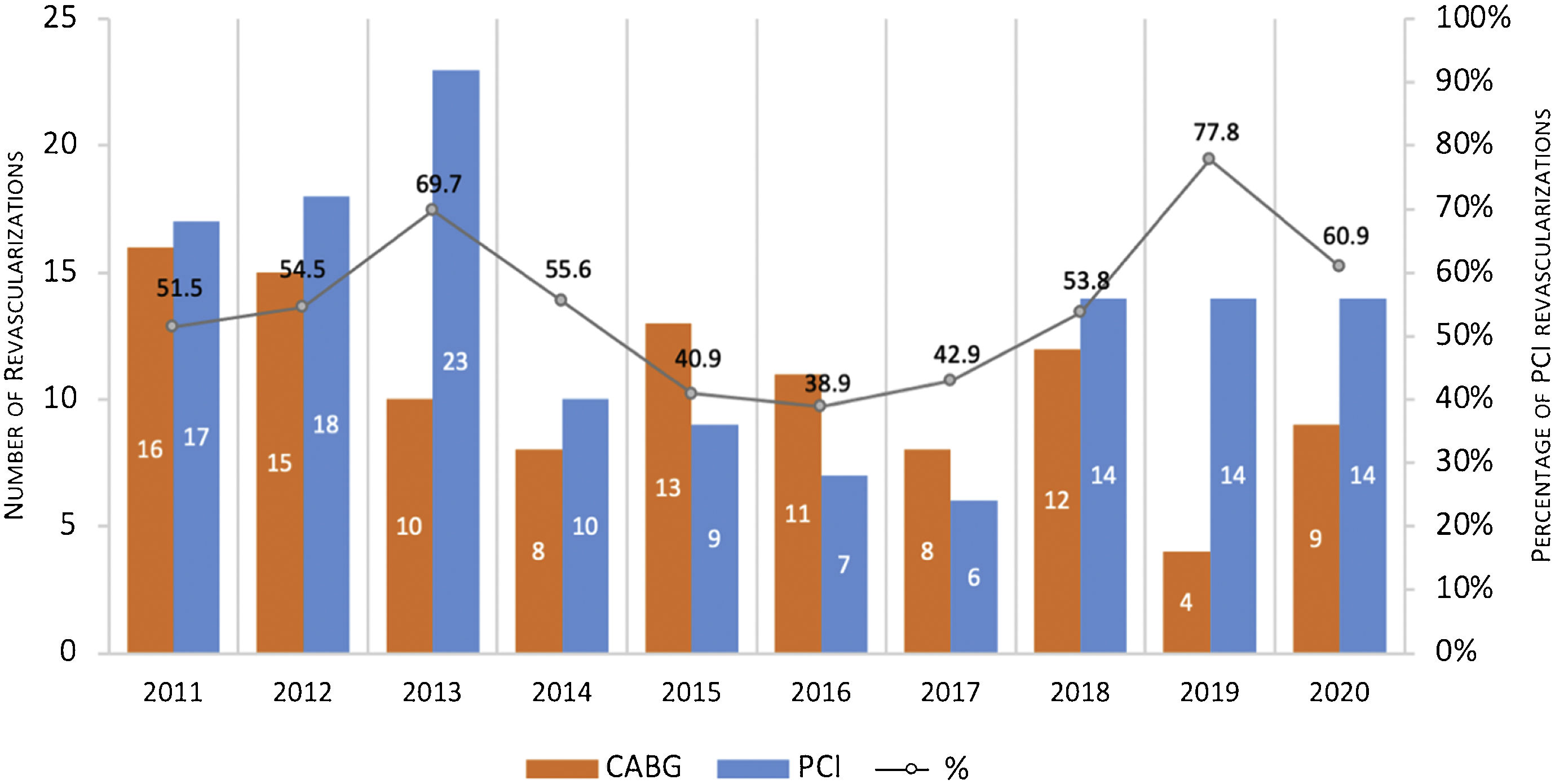

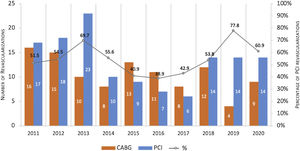

Trends in revascularization strategy over ten yearsBetween 2011 and 2020, PCI was the dominant choice for ULMCA revascularization with the exception of the years 2015, 2016 and 2017, where CABG accounted for 57.1–61.1% of the cases (Figure 2).

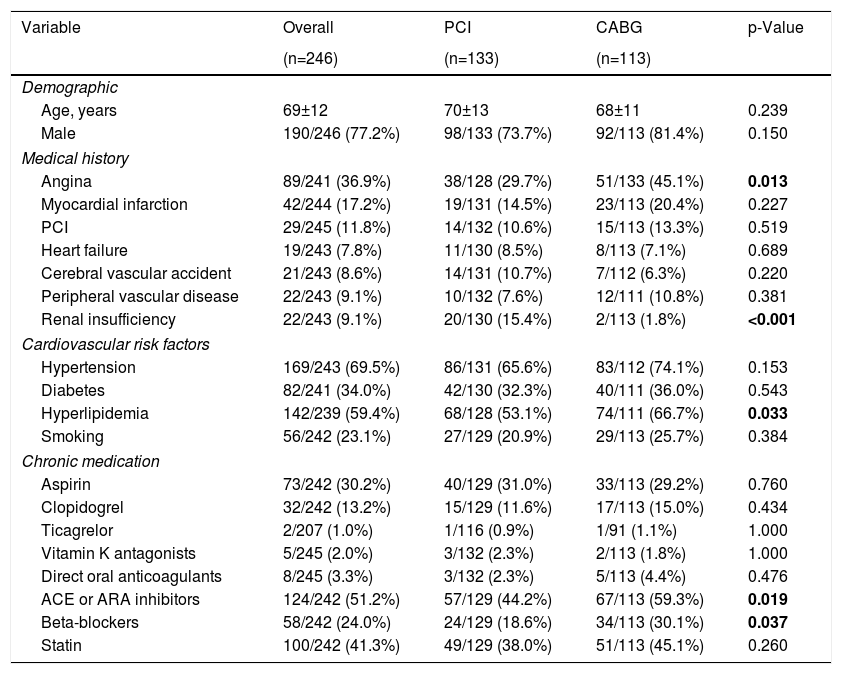

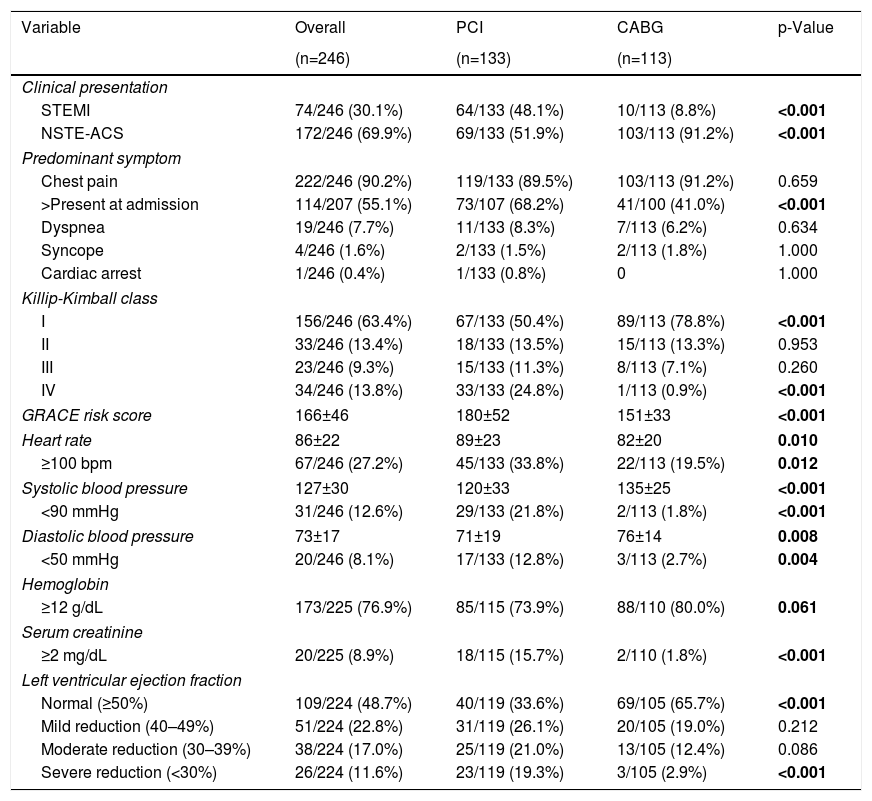

Baseline characteristics and clinical presentationBaseline characteristics and clinical presentation are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Mean age was 69±12 years and 77.2% were male. Most patients presented with ongoing NSTE-ACS (69.9%); 36.6% had heart failure (Killip-Kimball class ≥II) and 46.7% had compromised LVEF. Mean GRACE risk score21 was 166±46 (equivalent to an approximate 6% risk of in-hospital death).

Baseline clinical characteristics.

| Variable | Overall | PCI | CABG | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=246) | (n=133) | (n=113) | ||

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, years | 69±12 | 70±13 | 68±11 | 0.239 |

| Male | 190/246 (77.2%) | 98/133 (73.7%) | 92/113 (81.4%) | 0.150 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Angina | 89/241 (36.9%) | 38/128 (29.7%) | 51/133 (45.1%) | 0.013 |

| Myocardial infarction | 42/244 (17.2%) | 19/131 (14.5%) | 23/113 (20.4%) | 0.227 |

| PCI | 29/245 (11.8%) | 14/132 (10.6%) | 15/113 (13.3%) | 0.519 |

| Heart failure | 19/243 (7.8%) | 11/130 (8.5%) | 8/113 (7.1%) | 0.689 |

| Cerebral vascular accident | 21/243 (8.6%) | 14/131 (10.7%) | 7/112 (6.3%) | 0.220 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 22/243 (9.1%) | 10/132 (7.6%) | 12/111 (10.8%) | 0.381 |

| Renal insufficiency | 22/243 (9.1%) | 20/130 (15.4%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 169/243 (69.5%) | 86/131 (65.6%) | 83/112 (74.1%) | 0.153 |

| Diabetes | 82/241 (34.0%) | 42/130 (32.3%) | 40/111 (36.0%) | 0.543 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 142/239 (59.4%) | 68/128 (53.1%) | 74/111 (66.7%) | 0.033 |

| Smoking | 56/242 (23.1%) | 27/129 (20.9%) | 29/113 (25.7%) | 0.384 |

| Chronic medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 73/242 (30.2%) | 40/129 (31.0%) | 33/113 (29.2%) | 0.760 |

| Clopidogrel | 32/242 (13.2%) | 15/129 (11.6%) | 17/113 (15.0%) | 0.434 |

| Ticagrelor | 2/207 (1.0%) | 1/116 (0.9%) | 1/91 (1.1%) | 1.000 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 5/245 (2.0%) | 3/132 (2.3%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | 1.000 |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | 8/245 (3.3%) | 3/132 (2.3%) | 5/113 (4.4%) | 0.476 |

| ACE or ARA inhibitors | 124/242 (51.2%) | 57/129 (44.2%) | 67/113 (59.3%) | 0.019 |

| Beta-blockers | 58/242 (24.0%) | 24/129 (18.6%) | 34/113 (30.1%) | 0.037 |

| Statin | 100/242 (41.3%) | 49/129 (38.0%) | 51/113 (45.1%) | 0.260 |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARA: angiotensin II receptor antagonist; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

In bold, p-value < 0.05.

Clinical presentation.

| Variable | Overall | PCI | CABG | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=246) | (n=133) | (n=113) | ||

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| STEMI | 74/246 (30.1%) | 64/133 (48.1%) | 10/113 (8.8%) | <0.001 |

| NSTE-ACS | 172/246 (69.9%) | 69/133 (51.9%) | 103/113 (91.2%) | <0.001 |

| Predominant symptom | ||||

| Chest pain | 222/246 (90.2%) | 119/133 (89.5%) | 103/113 (91.2%) | 0.659 |

| >Present at admission | 114/207 (55.1%) | 73/107 (68.2%) | 41/100 (41.0%) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 19/246 (7.7%) | 11/133 (8.3%) | 7/113 (6.2%) | 0.634 |

| Syncope | 4/246 (1.6%) | 2/133 (1.5%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | 1.000 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1/246 (0.4%) | 1/133 (0.8%) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Killip-Kimball class | ||||

| I | 156/246 (63.4%) | 67/133 (50.4%) | 89/113 (78.8%) | <0.001 |

| II | 33/246 (13.4%) | 18/133 (13.5%) | 15/113 (13.3%) | 0.953 |

| III | 23/246 (9.3%) | 15/133 (11.3%) | 8/113 (7.1%) | 0.260 |

| IV | 34/246 (13.8%) | 33/133 (24.8%) | 1/113 (0.9%) | <0.001 |

| GRACE risk score | 166±46 | 180±52 | 151±33 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate | 86±22 | 89±23 | 82±20 | 0.010 |

| ≥100 bpm | 67/246 (27.2%) | 45/133 (33.8%) | 22/113 (19.5%) | 0.012 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 127±30 | 120±33 | 135±25 | <0.001 |

| <90 mmHg | 31/246 (12.6%) | 29/133 (21.8%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 73±17 | 71±19 | 76±14 | 0.008 |

| <50 mmHg | 20/246 (8.1%) | 17/133 (12.8%) | 3/113 (2.7%) | 0.004 |

| Hemoglobin | ||||

| ≥12 g/dL | 173/225 (76.9%) | 85/115 (73.9%) | 88/110 (80.0%) | 0.061 |

| Serum creatinine | ||||

| ≥2 mg/dL | 20/225 (8.9%) | 18/115 (15.7%) | 2/110 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | ||||

| Normal (≥50%) | 109/224 (48.7%) | 40/119 (33.6%) | 69/105 (65.7%) | <0.001 |

| Mild reduction (40–49%) | 51/224 (22.8%) | 31/119 (26.1%) | 20/105 (19.0%) | 0.212 |

| Moderate reduction (30–39%) | 38/224 (17.0%) | 25/119 (21.0%) | 13/105 (12.4%) | 0.086 |

| Severe reduction (<30%) | 26/224 (11.6%) | 23/119 (19.3%) | 3/105 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

NSTE-ACS: non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

In bold, p-value < 0.05.

The most severe patients were found in the percutaneous group. Compared with the CABG group, patients undergoing PCI presented more frequently ongoing STEMI (48.1% versus 8.8%, p<0.001), ongoing chest pain (68.2% versus 41.0%, p<0.001), cardiogenic shock (Killip-Kimball class IV; 24.8% versus 0.9%, p<0.001), and severely depressed LVEF (<30.0%; 17.3% versus 2.7%, p<0.001). They also had higher values of serum creatinine (≥2 mg/dL; 15.7% versus 1.8%, p<0.001) and presented significantly higher GRACE risk score21 of 180±52, corresponding to an approximate 10% of in-hospital death.

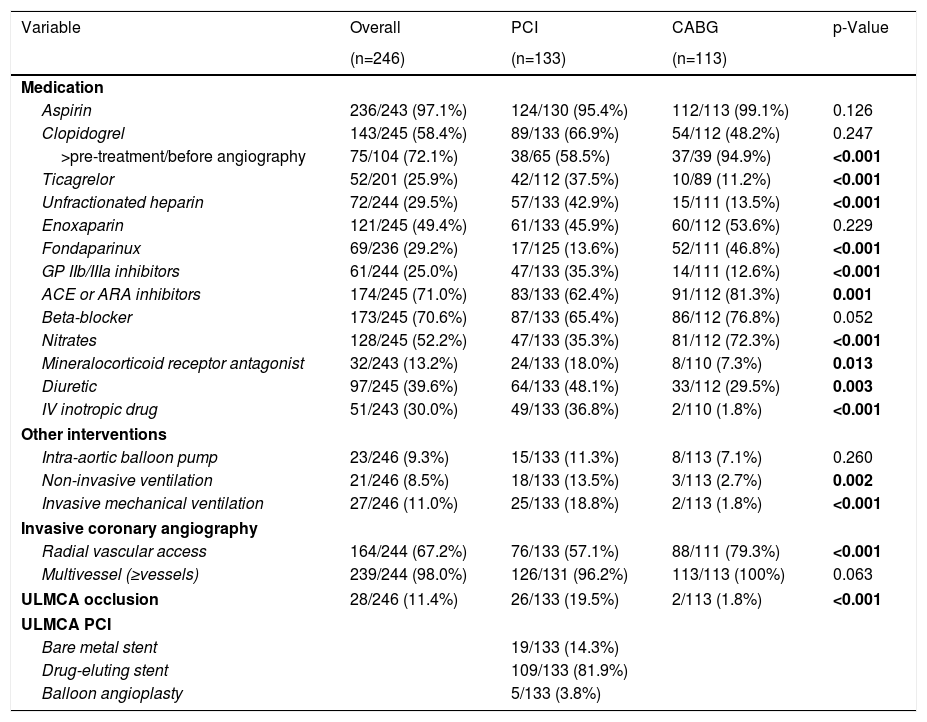

Hospital managementTable 3 illustrates hospital management of the disease. Time from hospital admission to revascularization was higher in surgical group with a median time to CABG of 4.5 days (IQR 1.5–8.6 days) compared to 0 days (IQR 0–1 day) to PCI (p<0.001). Drug-eluting stents were used in 81.9% of those who underwent PCI and angiographic success rate was 93.2%. Patients who underwent percutaneous revascularization took more frequently glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (35.3% versus 12.6%, p<0.001), diuretics (48.1% vs. 29.5%, p=0.003) and intravenous inotropic drugs (36.8% vs. 1.8%, p<0.001). In addition, PCI patients had a higher need of both non-invasive (13.5% vs. 2.7%, p=0.002) and invasive mechanical (18.8% vs. 1.8%, p<0.001) ventilation during hospitalization.

Hospital management.

| Variable | Overall | PCI | CABG | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=246) | (n=133) | (n=113) | ||

| Medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 236/243 (97.1%) | 124/130 (95.4%) | 112/113 (99.1%) | 0.126 |

| Clopidogrel | 143/245 (58.4%) | 89/133 (66.9%) | 54/112 (48.2%) | 0.247 |

| >pre-treatment/before angiography | 75/104 (72.1%) | 38/65 (58.5%) | 37/39 (94.9%) | <0.001 |

| Ticagrelor | 52/201 (25.9%) | 42/112 (37.5%) | 10/89 (11.2%) | <0.001 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 72/244 (29.5%) | 57/133 (42.9%) | 15/111 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Enoxaparin | 121/245 (49.4%) | 61/133 (45.9%) | 60/112 (53.6%) | 0.229 |

| Fondaparinux | 69/236 (29.2%) | 17/125 (13.6%) | 52/111 (46.8%) | <0.001 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 61/244 (25.0%) | 47/133 (35.3%) | 14/111 (12.6%) | <0.001 |

| ACE or ARA inhibitors | 174/245 (71.0%) | 83/133 (62.4%) | 91/112 (81.3%) | 0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 173/245 (70.6%) | 87/133 (65.4%) | 86/112 (76.8%) | 0.052 |

| Nitrates | 128/245 (52.2%) | 47/133 (35.3%) | 81/112 (72.3%) | <0.001 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 32/243 (13.2%) | 24/133 (18.0%) | 8/110 (7.3%) | 0.013 |

| Diuretic | 97/245 (39.6%) | 64/133 (48.1%) | 33/112 (29.5%) | 0.003 |

| IV inotropic drug | 51/243 (30.0%) | 49/133 (36.8%) | 2/110 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Other interventions | ||||

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 23/246 (9.3%) | 15/133 (11.3%) | 8/113 (7.1%) | 0.260 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 21/246 (8.5%) | 18/133 (13.5%) | 3/113 (2.7%) | 0.002 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 27/246 (11.0%) | 25/133 (18.8%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Invasive coronary angiography | ||||

| Radial vascular access | 164/244 (67.2%) | 76/133 (57.1%) | 88/111 (79.3%) | <0.001 |

| Multivessel (≥vessels) | 239/244 (98.0%) | 126/131 (96.2%) | 113/113 (100%) | 0.063 |

| ULMCA occlusion | 28/246 (11.4%) | 26/133 (19.5%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| ULMCA PCI | ||||

| Bare metal stent | 19/133 (14.3%) | |||

| Drug-eluting stent | 109/133 (81.9%) | |||

| Balloon angioplasty | 5/133 (3.8%) | |||

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARA: angiotensin II receptor antagonist; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; GP: glycoprotein; IV: intravenous; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; ULMCA: unprotected left main coronary artery.

In bold, p-value < 0.05.

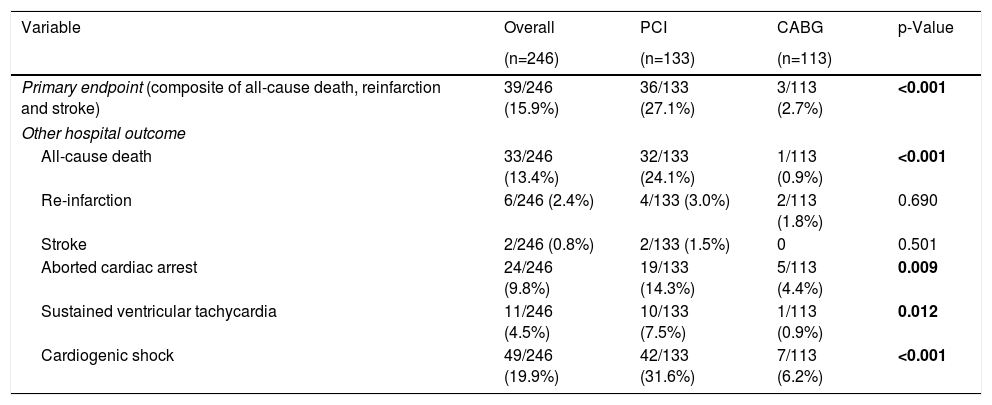

Median length of hospital stay was seven days (IQR 2–9 days) and did not differ between the two groups. Primary endpoint occurred in 39 patients (15.9%), and was significantly higher in those that underwent percutaneous revascularization (27.1% vs. 2.7%, p<0.001). The same was observed for in-hospital all-cause death (24.1% vs. 0.9%, p<0.001). There was no between-group difference for re-infarction and stroke. Table 4 lists the in-hospital outcomes.

Hospital outcomes.

| Variable | Overall | PCI | CABG | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=246) | (n=133) | (n=113) | ||

| Primary endpoint (composite of all-cause death, reinfarction and stroke) | 39/246 (15.9%) | 36/133 (27.1%) | 3/113 (2.7%) | <0.001 |

| Other hospital outcome | ||||

| All-cause death | 33/246 (13.4%) | 32/133 (24.1%) | 1/113 (0.9%) | <0.001 |

| Re-infarction | 6/246 (2.4%) | 4/133 (3.0%) | 2/113 (1.8%) | 0.690 |

| Stroke | 2/246 (0.8%) | 2/133 (1.5%) | 0 | 0.501 |

| Aborted cardiac arrest | 24/246 (9.8%) | 19/133 (14.3%) | 5/113 (4.4%) | 0.009 |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia | 11/246 (4.5%) | 10/133 (7.5%) | 1/113 (0.9%) | 0.012 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 49/246 (19.9%) | 42/133 (31.6%) | 7/113 (6.2%) | <0.001 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

In bold, p-value < 0.05.

Unadjusted logistic regression is available in Supplementary Table 1. After adjustment for covariates, cardiogenic shock (OR 6.79; 95% CI 1.94–23.76; p=0.039), hemoglobin level <12 g/dL (OR 3.51; 95% CI 1.22–10.13; p=0.020) and creatinine level ≥2 mg/dL (OR 3.45; 95% CI 1.06–11.16; p=0.039) at admission were associated with the occurrence of the primary endpoint. Inversely, CABG (OR 0.16; 95% CI 0.04–0.64; p=0.009) and radial artery access during invasive coronary angiography (OR 0.28; 95% CI 0.09–0.82; p=0.020) were associated with a lower occurrence of MACCE.

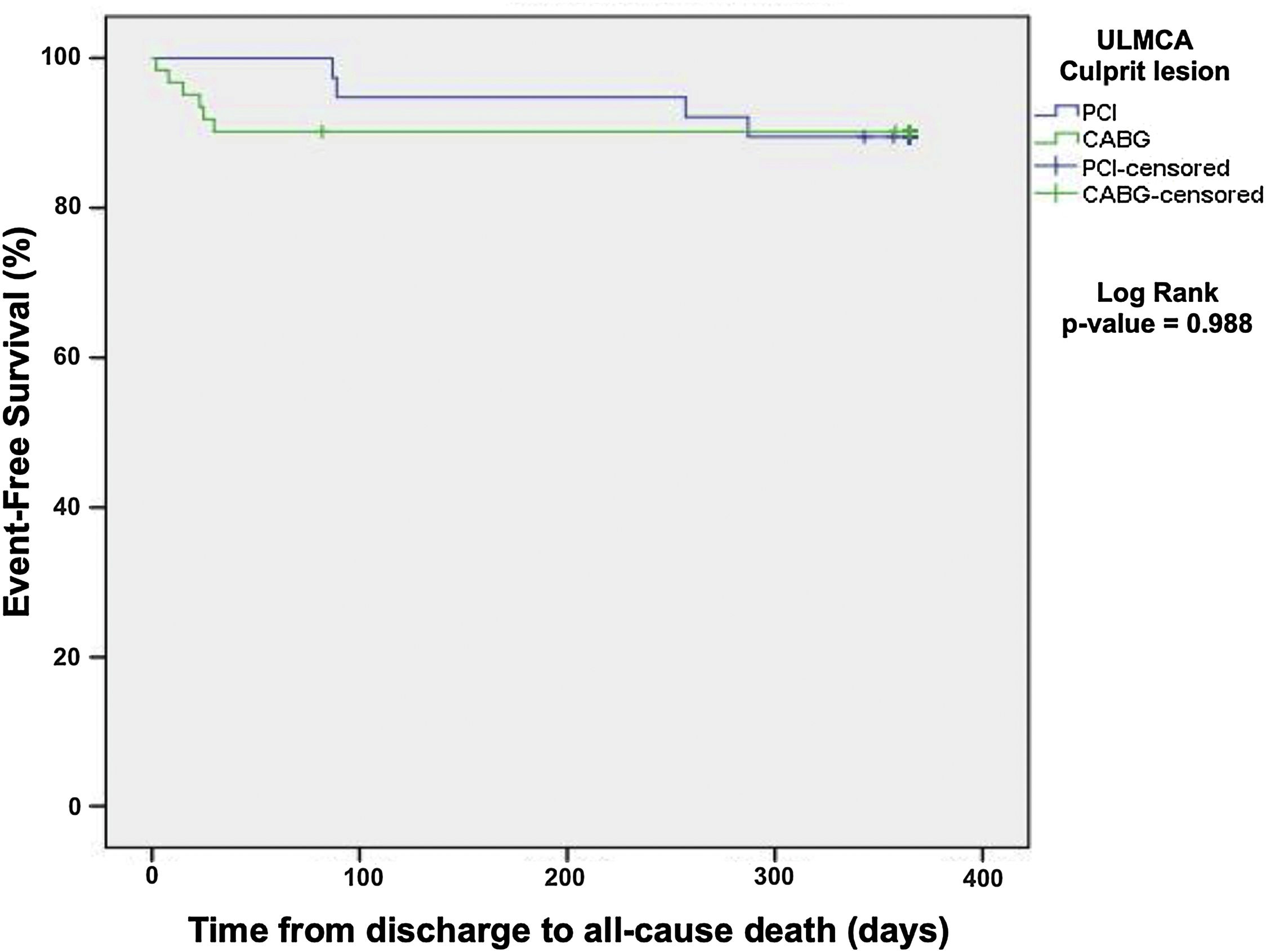

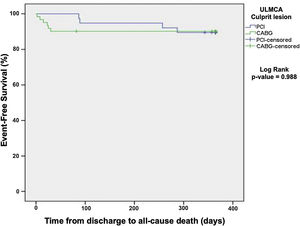

One-year all-cause mortality was 10.1% and did not differ among patients treated with percutaneous versus surgical revascularization (Kaplan-Meier, log rank p=0.988, Figure 3).

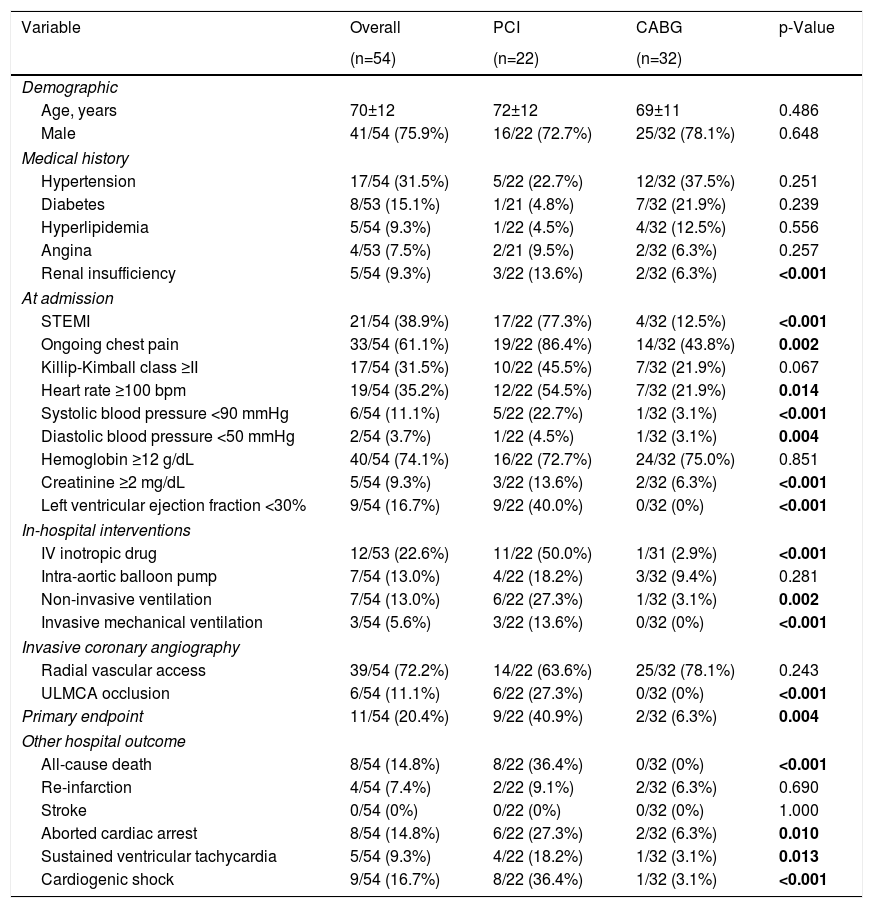

Propensity scoreAccording to propensity score for sample homogenization (Table 5 and Supplementary Table 2), 54 patients were matched. Similar to the nonmatched population analysis, patients undergoing PCI presented more frequently ongoing STEMI, ongoing chest pain, severely depressed LVEF and serum creatinine level ≥2 mg/dL at admission. Primary endpoint occurrence was significantly higher in patients who underwent percutaneous revascularization.

Hospital outcomes after propensity score matching.

| Variable | Overall | PCI | CABG | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=54) | (n=22) | (n=32) | ||

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, years | 70±12 | 72±12 | 69±11 | 0.486 |

| Male | 41/54 (75.9%) | 16/22 (72.7%) | 25/32 (78.1%) | 0.648 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 17/54 (31.5%) | 5/22 (22.7%) | 12/32 (37.5%) | 0.251 |

| Diabetes | 8/53 (15.1%) | 1/21 (4.8%) | 7/32 (21.9%) | 0.239 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5/54 (9.3%) | 1/22 (4.5%) | 4/32 (12.5%) | 0.556 |

| Angina | 4/53 (7.5%) | 2/21 (9.5%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | 0.257 |

| Renal insufficiency | 5/54 (9.3%) | 3/22 (13.6%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| At admission | ||||

| STEMI | 21/54 (38.9%) | 17/22 (77.3%) | 4/32 (12.5%) | <0.001 |

| Ongoing chest pain | 33/54 (61.1%) | 19/22 (86.4%) | 14/32 (43.8%) | 0.002 |

| Killip-Kimball class ≥II | 17/54 (31.5%) | 10/22 (45.5%) | 7/32 (21.9%) | 0.067 |

| Heart rate ≥100 bpm | 19/54 (35.2%) | 12/22 (54.5%) | 7/32 (21.9%) | 0.014 |

| Systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg | 6/54 (11.1%) | 5/22 (22.7%) | 1/32 (3.1%) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure <50 mmHg | 2/54 (3.7%) | 1/22 (4.5%) | 1/32 (3.1%) | 0.004 |

| Hemoglobin ≥12 g/dL | 40/54 (74.1%) | 16/22 (72.7%) | 24/32 (75.0%) | 0.851 |

| Creatinine ≥2 mg/dL | 5/54 (9.3%) | 3/22 (13.6%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <30% | 9/54 (16.7%) | 9/22 (40.0%) | 0/32 (0%) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital interventions | ||||

| IV inotropic drug | 12/53 (22.6%) | 11/22 (50.0%) | 1/31 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 7/54 (13.0%) | 4/22 (18.2%) | 3/32 (9.4%) | 0.281 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 7/54 (13.0%) | 6/22 (27.3%) | 1/32 (3.1%) | 0.002 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 3/54 (5.6%) | 3/22 (13.6%) | 0/32 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Invasive coronary angiography | ||||

| Radial vascular access | 39/54 (72.2%) | 14/22 (63.6%) | 25/32 (78.1%) | 0.243 |

| ULMCA occlusion | 6/54 (11.1%) | 6/22 (27.3%) | 0/32 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Primary endpoint | 11/54 (20.4%) | 9/22 (40.9%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | 0.004 |

| Other hospital outcome | ||||

| All-cause death | 8/54 (14.8%) | 8/22 (36.4%) | 0/32 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Re-infarction | 4/54 (7.4%) | 2/22 (9.1%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | 0.690 |

| Stroke | 0/54 (0%) | 0/22 (0%) | 0/32 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Aborted cardiac arrest | 8/54 (14.8%) | 6/22 (27.3%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | 0.010 |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia | 5/54 (9.3%) | 4/22 (18.2%) | 1/32 (3.1%) | 0.013 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 9/54 (16.7%) | 8/22 (36.4%) | 1/32 (3.1%) | <0.001 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; IV: intravenous; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; ULMCA: unprotected left main coronary artery.

In bold, p-value < 0.05.

The main findings of this multicenter analysis were the following: (1) ULMCA was the culprit lesion of a low percentage of ACS; (2) PCI was preferred to CABG as the revascularization method; (3) PCI patients presented higher clinical risk and were treated earlier than CABG patients; (4) after adjustment, surgical revascularization was strongly and significantly associated with in-hospital survival; (5) nevertheless, PCI was a feasible treatment with a high angiographic success and acceptable in-hospital outcome; (6) no difference was found at one-year all-cause mortality based on the revascularization method employed during the acute phase.

The incidence of ACS due to ULMCA culprit lesion is reported to be 0.8%–5.4%, however this could be underestimated considering the number of patients who died before arriving at hospital.7,22

In the acute scenario, PCI has become the most common revascularization treatment of the ULMCA, offering prompt reperfusion and high angiographic success rate. This reflects the optimization of the procedure including bifurcation techniques and intravascular imaging.23,24 Similarly, PCI was preferred to CABG in our analysis, with the exception of the years around the publication of the EXCEL (Evaluation of XIENCE versus Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery for Effectiveness of Left Main Revascularization) trial17 and the NOBLE (Nordic-Baltic-British left main revascularization) trial.18

Regarding in-hospital outcomes, the primary endpoint was significantly higher in patients undergoing percutaneous revascularization, which occurred at the expense of all-cause death. Of note, no difference was observed in the occurrence of re-infarction or stroke between the groups. These findings are different from previous publications that demonstrated an early hazard for re-infarction including periprocedural MI in PCI patients and for stroke in CABG patients.13,17,18 Reported in-hospital mortality varied remarkably between published studies (from <1% to 64%) related with the occurrence of cardiogenic shock, which has been identified as an independent risk factor for adverse events, as our analysis demonstrates.7,8,22–26 Besides the high rate of cardiogenic shock, mechanical circulatory support was used in only 9% of cases and 20% of cardiogenic shock patients submitted to PCI, a number that is significantly lower than that reported by other studies, which ranged from 13–100% and 80–100% respectively.25,27–29 This can be explained for two reasons. First, the ProACS Registry only collect data about intra-aortic balloon pump missing the newer mechanical support devices. Second, hemodynamic benefit in cardiogenic shock has not been translated into improved survival and the level of recommendation of these devices continue low.1–4,30 Nevertheless, national data concerning cardiogenic shock management and current use of mechanical support devices are still missing. We also demonstrated that hemoglobin level <12 g/dL and creatinine level ≥2 mg/dL at admission were strong predictors of worse prognosis. Actually, anemia and renal function impairment have been found to be predictors of bleeding, ischemic events and mortality in previous studies.31,32 On the other hand, the radial approach was associated with reduced early mortality, the same finding reported by Almudarra et al.26 Whether radial artery access reflects a less sick population, more skilled operators and/or a lower rate of vascular/bleeding complications is not possible to determine by this study. After adjustment, surgical revascularization was also strongly and significantly associated with in-hospital survival.

Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass graftAccording to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, CABG is recommend for the treatment of non-urgent ULMCA disease regardless of SYNTAX score.1,5,33 Percutaneous revascularization is recommended in cases of low SYNTAX score, should be considered in intermediate SYNTAX score and is not recommended in high SYNTAX score.33 But evidence-based guidelines do not unequivocally address the optimal timing and mode of revascularization of patients with ACS and ULMCA culprit lesion.

Concerning timing, ESC guidelines recommend an immediate invasive strategy (<2 hours) in patients with STEMI or NSTEMI with very high risk criteria such as hemodynamically instability, heart failure and the presence of electrocardiographic changes suggestive of severe LMCA or multivessel disease.3,4 A revascularization strategy in the first 24 hours is recommended in the remaining NSTEMI and extends to 72 hours in the case of unstable angina.4,33 In our population, the recommended revascularization timing was not fulfilled in the surgical patients, which is probably related to the high rate of pre-treatment with clopidogrel, and the lower risk profile of the patients who underwent CABG.

With regard to the mode of revascularization, current guidelines recommend a heart team approach to revascularization decisions in patients with ULMCA culprit lesion and a similar revascularization modality as those for chronic disease.2,4 The exception are patients with cardiogenic shock or coronary flow impairment, when PCI is considered reasonable to improve survival if it can be performed more rapidly and safely than CABG.1,4 These recommendations are based on randomized trials and metanalysis that compared PCI vs. CABG for ULMCA revascularization. They were, however, not dedicated to the acute setting.10–19,34–38 Clinical outcomes in patients with ACS due to ULMCA culprit lesion according to the revascularization method have only been reported in non-randomized studies with exception of a subanalysis of the EXCEL trial (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).39

In 2015, Grundeken et al. published the first study comparing patients with MI due to ULMCA culprit lesion treated with PCI and CABG.22 The authors assessed 84 patients and found that 30-day all-cause mortality was greater in the percutaneous group (64% versus 24%). Previously, Montalescot et al. had reported outcomes of 1799 patients with significant LMCA disease and ACS (not necessarily as a culprit lesion) enrolled in the GRACE registry.23 In-hospital death was also higher in the percutaneous group compared to the surgical group (11% versus 5%). Similar to our study, PCI was used in the highest risk patients reflected by a superior incidence of STEMI, cardiogenic shock, and superior values of GRACE risk score. PCI patients were also treated earlier than CABG patients, thus emphasizing treatment urgency, accumulating all the risk of the revascularization procedure in the first 24 h and excluding patients who died or developed a contraindication to surgery during the waiting period. In addition, PCI presented a high angiographic success rate suggesting that clinical risk and hemodynamical instability rather than revascularization treatment itself may be a dominant factor related to mortality. Whether the difference in survival is due to the treatment strategies themselves or to differences in the patient populations undergoing such treatment is not possible to determine in these observational studies.

Concerning mid-term outcomes, patients who survived to discharge seemed to have a reasonable prognosis with a one-year all-cause death of 10.1% and no difference between PCI versus CABG groups. This is in accordance with most previously conducted studies that revealed a one-year mortality rate varying from 10 to 20% and similar results in percutaneous and surgical patients (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).8,36–38 An analysis of the multinational DELTA registry, which included 379 patients with ULMCA disease presenting with STEMI or NSTEMI, found no difference at three years’ occurrence of the primary endpoint (all-cause death, MI or cerebrovascular events) between PCI and CABG (hazard ratio (HR) 1.25; 95% CI 0.52–3.00, p=0.611).27 More recently, a sub-analysis of the EXCEL trial included 1897 patients with LMCA revascularization and low to intermediate SYNTAX scores, 39.3% of whom had ACS, revealed that three year rate of the primary endpoint (all-cause death, MI or stroke) was also similar between PCI and CABG (adjusted HR 0.82; 95% CI: 0.54–1.26; p=0.340).39

Lastly, focusing on non-specific acute setting randomized trials: The PRECOMBAT trial,10–12 the SYNTAX trial,13–15 and the EXCEL trial16,17 showed similar rates of long-term adverse events in patients undergoing LMCA PCI or CABG. In contrast, the NOBLE trial found that the composite endpoint of all-cause death, non-procedural MI, any repeat coronary revascularization, and stroke was significantly higher with PCI compared to CABG. It was concluded that surgery revascularization offered a better clinical outcome than percutaneous revascularization in LMCA disease.18,19 It is important to note that the NOBLE trial explicitly excluded STEMI patients and NSTE-ACS patients comprising less than 20% of the study cohort.

The main strength and clinical contribution of this study is that data comparing percutaneous and surgical revascularization in patients with ACS due to ULMCA culprit lesion are very limited. Reports for this specific patient subgroup are needed and provide a crucial clinical contribution to a better understanding of both risk and clinical outcomes.

LimitationsFirst, it was an observational study and is therefore subject to the underlying limitations of this type of clinical investigation including non-randomization. Differences between the institutions involved in the research, although representative of the reality of the country's health system, may have introduced an unintentional bias. Data on devices and technical considerations used during PCI or CABG procedures were not recorded and may have influenced results. Data on the complexity of coronary artery disease such as SYNTAX score as well risk profile for cardiac surgery as assessed by EuroSCORE or STS score were also not collected. Lastly, it would have been of interest to know how many patients underwent PCI after having been rejected for CABG and how many patients died while waiting for surgical revascularization.

ConclusionsThe present study suggests that ACS due to a ULMCA culprit lesion is a rare but serious situation with high risk of adverse clinical events, including hemodynamic instability and death. PCI is the most common strategy of revascularization in the acute setting and is generally preferred in very unstable patients presenting a high angiographic success and acceptable in-hospital outcomes. In contrast, CABG surgery is preferred in low-risk patients. At one-year follow-up, PCI and CABG confer a similar prognosis. Therefore, the two modes of revascularization appear complementary in this high risk cohort. Larger, randomized studies are still required to better understand the acute interventional care of this cohort.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank to Maria de Fátima Loureiro, who was responsible for the statistical analysis.