In patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS), an invasive strategy is recommended. However, the optimal timing to perform coronary angiography (CA) remains undetermined, and this issue has become particularly relevant since the 2020 European guidelines restricted pre-treatment (PT) with P2Y12 antagonists.

ObjectiveTo assess the prognostic value of an early (ES; <24 h) versus a delayed strategy (DS; >24 h) when no loading dose of a P2Y12 antagonist is given as PT in NSTE-ACS.

MethodsA retrospective analysis was carried out of patients admitted with NSTE-ACS included in the Portuguese Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes between 2015 and 2019. Patients undergoing PT were excluded. Patients were divided into two groups regarding the timing of CA (<24 h vs. >24 h). Independent predictors of a composite of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes at one year were assessed by multivariate logistic regression.

ResultsA total of 619 patients were assessed, mean age 63±12 years, 77.5% male. On CA, 6.1% had normal coronary arteries, 49.6% single-vessel disease and 44.8% multivessel disease. Revascularization was performed in 88.6%. Pending CA, 66.0% were medicated with ticagrelor and 42.3% with clopidogrel. Adverse in-hospital outcomes were not significantly different between groups, except for more major bleeding in the DS group. The one-year composite endpoint of total mortality and cardiovascular rehospitalization occurred in 8.9%, with no difference between groups.

ConclusionIn patients with NSTE-ACS in the absence of PT with a P2Y12 antagonist, an early invasive strategy was not associated with more in-hospital adverse outcomes or a reduction of total mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes at one year.

Em doentes com síndromes coronárias agudas sem supradesnivelamento de ST (SCA-SST), está recomendada uma estratégia invasiva. Contudo, o melhor timing para realizar a coronariografia (CA) permanece indeterminado tornando-se este tópico particularmente relevante uma vez que as guidelines Europeias de 2020 restringiram o pré-tratamento (PT) com antagonistas P2Y12.

ObjetivoAvaliar o valor prognóstico de uma estratégia precoce (EP; <24 h) versus diferida (ED; >24 h) quando não é administrada dose de carga de um antagonista P2Y12 como pré-tratamento em doentes com SCA-SST.

Material e métodosAnálise retrospetiva de doentes admitidos com SCA-SST incluídos no Registo Português de Síndromes Coronárias Agudas entre 2015-19. Doentes submetidos a pré-tratamento foram excluídos. Os doentes foram divididos em dois grupos de acordo com o timing da CA (<24 h versus >24). Uma regressão logística multivariada foi realizada para avaliar os fatores preditores do endpoint composto mortalidade por todas as causas e re-hospitalização cardiovascular a um ano.

Resultados619 doentes foram avaliados, idade média 63±12 anos, 77,5% género masculino. Na CA, 6,1% tinham coronárias normais, 49,6% doença de 1-vaso e 44,8% doença multivaso. A revascularização foi realizada em 88,6%. Durante a CA, 66,0% foram medicados com ticagrelor e 42,3% clopidogrel. Os outcomes adversos intra-hospitalares não foram significativamente diferentes entre os grupos, exceto mais hemorragia major no grupo de ED. O endpoint composto de mortalidade total e rehospitalização cardiovascular a 1-ano ocorreu em 8,9%, sem diferença entre os grupos.

ConclusãoEm doentes com SCA-SST na ausência de pré-tratamento com um antagonista P2Y12, uma estratégia invasiva precoce não esteve associada a mais outcomes adversos intra-hospitalares ou a redução de mortalidade total e re-hospitalização cardiovascular a um ano.

In patients with high-risk non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS), a routine invasive strategy is recommended since it leads to a reduction in the rate of myocardial infarction (MI), refractory angina, rehospitalization and death. Coronary angiography (CA) can confirm the diagnosis and enable coronary revascularization when required.1–4 However, the optimal timing to perform CA remains undetermined because no significant difference regarding clinical outcomes has been observed in several trials comparing early (<24 h) vs. delayed (24-72 h) strategies, except a trend toward fewer recurrent ischemic events and lower mortality with an early strategy (ES) in higher-risk subgroups.1,2 An ES enables rapid revascularization, preventing acute vessel closure and avoiding recurrent ischemic events, while a delayed strategy (DS) enables initiation of medical therapy to stabilize platelets and reduce thrombus burden, facilitating coronary revascularization.1,2,4

Besides CA, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 antagonist is the standard of care in these patients.5–7 Pre-treatment (PT) is defined as a strategy in which antiplatelet drugs, usually a P2Y12 antagonist, are given before CA when the coronary anatomy is unknown.6–8 PT was widely used in previous studies, in accordance with the guidelines of the time, with the theoretical advantage of providing more ischemic protection. However, the more recent 2020 European guidelines on the management of NSTE-ACS only recommend PT in patients with NSTE-ACS who are not scheduled to undergo an early invasive strategy and do not have a high bleeding risk (class IIb, level of evidence C).8

In this new era, the restriction of PT may influence the choice of timing between an ES and a DS. To the best of our knowledge, only one trial, Early or Delayed Revascularization for Intermediate and High-Risk Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes (EARLY), has investigated the optimal timing of an invasive strategy in this clinical setting without PT with P2Y12-antagonists.1,9 The present study aims to assess the prognostic value of an ES when no loading dose of a P2Y12 antagonist is given as PT in a Portuguese cohort of NSTE-ACS patients regarding all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes at one year.

MethodsPatient selectionThe Portuguese Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (ProACS) is a national voluntary multicenter registry of patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes. Patients were eligible for this study if they were diagnosed with high- or very high-risk NSTE-ACS and an invasive strategy was planned. Non-ST-segment elevation MI was defined as acute myocardial injury with clinical evidence of acute myocardial ischemia and detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac troponin values with at least one value above the 99th percentile, in accordance with the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) and European guidelines for the management of NSTE-ACS.8,10 The main exclusion criteria were medication with any P2Y12 antagonist prior to the index hospitalization, low-risk NSTE-ACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome or MI of undetermined location, PT with a loading dose of any P2Y12 antagonist before CA, and initial proposal for conservative treatment (and therefore not undergoing CA). Baseline patient demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors and other relevant personal background, clinical, laboratory, echocardiographic and angiographic data, and medications of all patients were recorded. This was a retrospective cohort study, but all data were collected prospectively during the index hospitalization.

Patient data in ProACS is anonymized at all times, and the registry has been approved by the national authorities and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 01642329). All ethical requirements in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 were met. Written informed consent for the introduction of patient data into the registry has been available since 2010 and is applied after approval by the ethics committee of each hospital center.

Coronary angiography and revascularization procedureThe starting time to calculate the timing of the intervention was designated as the time of hospital admission. The only significant difference between the two patient groups was the timing of the invasive procedure (<24 h vs. >24 h). Patients pre-treated with a P2Y12 antagonist were excluded. The loading doses of P2Y12 antagonists were given at the time of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in both groups. Aspirin and anticoagulant agents could be administered at any time according to center and physician protocols. CA was performed according to the guidelines.8 Procedural medications, including heparin or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, were administered and coronary revascularization was performed at the discretion of the interventional cardiologist, which in some patients included staged procedures. Significant lesions were defined as ≥50% lesions in a major epicardial vessel. Patients with coronary anatomy not suitable for revascularization by PCI were presented at the heart team conference with a view to performing revascularization by coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Outcomes and follow-upThe clinical outcomes were in-hospital adverse events and mortality and a composite of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes at one year after discharge. In-hospital outcomes were recorded for all patients. A total of 408 patients (65.9%) were followed for one year after the index hospitalization. The follow-up data were obtained by a nurse or doctor at each cardiology center by reviewing medical records or through telephone interview with patients.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as absolute number and percentage. Categorical data were analyzed by the chi-square test and continuous data by the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Logistic regression models using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis were used to identify independent predictors of the one-year composite endpoint.

ResultsStudy populationA total of 6470 NSTE-ACS patients were admitted to this Portuguese registry between 2015 and 2019. Of these, 739 patients were excluded for belonging to the low-risk NSTE-ACS group, 1035 due to absence of CA and 2491 due to lack of information regarding CA or PT. Seventy-two patients were under a P2Y12 antagonist prior to the index hospitalization and 1514 patients were treated with a loading dose of a P2Y12 antagonist as PT, so the final population was thus composed of 619 subjects. Of these, 371 (59.9%) underwent CA as an ES and the other 248 (40.1%) as a DS.

The mean age was 63±12 years in the overall population and 77.5% were male. Patients proposed for an ES tended to be younger (63±11 vs. 64±12 years, p=0.115). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups and are displayed in Table 1. There was a high prevalence of known coronary artery disease: 37.0% had angina pectoris, 17.9% previous MI, 13.6% previous PCI and 4.8% CABG. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups regarding cardiovascular risk factors or other comorbidities, except for chronic kidney disease (CKD), which was less prevalent in the ES group (0.8 vs. 4.5%, p=0.003). There was a trend toward an ES in patients with fewer cardiovascular risk factors, except for smoking, and less coronary artery disease. Altogether, 22.5% of the patients were receiving long-term aspirin and none was under any P2Y12 antagonist at the time of hospitalization.

Baseline characteristics of patients admitted with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome.

| Overall (n=619) | Early strategy (n=371) | Delayed strategy (n=248) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, years, n (years) | 619/619 (63±12) | 371/371 (63±11) | 248/248 (64±12) | 0.115 |

| Male, n (%) | 480/619 (77.5) | 288/371 (77.6) | 192/248 (77.4) | 0.951 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Smoking, n (%) | 219/619 (35.4) | 138/371 (37.2) | 81/248 (32.7) | 0.247 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 401/617 (65.0) | 235/369 (63.7) | 166/248 (66.9) | 0.407 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 177/616 (28.7) | 102/369 (27.6) | 75/247 (30.4) | 0.464 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 354/614 (57.7) | 209/366 (57.1) | 145/248 (58.5) | 0.737 |

| CAD family history, n (%) | 33/615 (5.4) | 19/368 (5.2) | 14/247 (5.7) | 0.785 |

| Previous history | ||||

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 229/619 (37.0) | 136/371 (36.7) | 93/248 (37.5) | 0.832 |

| MI, n (%) | 111/619 (17.9) | 65/371 (17.5) | 46/248 (18.5) | 0.744 |

| PCI, n (%) | 84/617 (13.6) | 50/369 (13.6) | 34/248 (13.7) | 0.955 |

| CABG, n (%) | 30/619 (4.8) | 15/371 (4.0) | 15/248 (6.0) | 0.255 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 20/619 (3.2) | 9/371 (2.4) | 11/248 (4.4) | 0.166 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 31/619 (5.0) | 22/371 (5.9) | 9/248 (3.6) | 0.198 |

| CKD, n (%) | 14/615 (2.3) | 3/368 (0.8) | 11/247 (4.5) | 0.003 |

| PAD, n (%) | 32/617 (5.2) | 20/369 (5.4) | 12/248 (4.8) | 0.750 |

| Previous bleeding | 11/614 (1.8) | 5/367 (1.4) | 6/247 (2.4) | 0.364 |

| Previous medication | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 139/619 (22.5) | 84/371 (22.6) | 55/248 (22.2) | 0.892 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; MI: myocardial infarction; PAD: peripheral artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

At hospital admission, patients proposed for an ES presented lower Killip class, although this was not statistically significant (Killip >I 8.5 vs. 6.5%, p=0.348). They also presented a trend toward lower creatinine and higher hemoglobin levels at admission and during hospitalization (Table 2). Mean GRACE score was similar between the ES and DS groups (121±31 vs. 122±31, p=0.879, respectively). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was almost the same in both groups (59±11 vs. 59±10%, p=0.998). During hospitalization, patients proposed for an ES less frequently needed non-invasive ventilatory support (0.5 vs. 1.6%, p=0.225).

Clinical presentation, coronary angiography and other interventions.

| Overall (n=619) | Early strategy (n=371) | Delayed strategy (n=248) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killip class >I (%) | 45/619 (7.3) | 24/371 (6.5) | 21/248 (8.5) | 0.348 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Cr (admission), n (mg/dl) | 92/92 (1±0.1) | 50/50 (1.0±0.1) | 42/42 (1.0±0.2) | 0.901 |

| Cr (maximum), n (mg/dl) | 85/85 (1.3±1.3) | 48/48 (1.1±0.3) | 37/37 (1.6±1.9) | 0.123 |

| Hb (admission), n (g/dl) | 62/62 (14.5±1.7) | 39/39 (14.6±1.7) | 23/23 14. (3±1.8) | 0.496 |

| Hb (minimum), n (g/dl) | 44/44 (13.5±1.5) | 27/27 13.7±1.5) | 17/17 13. (1±1.6) | 0.231 |

| Platelets, n (103/mm3) | 604/604 (233±73) | 360/360 (230±81) | 244/244 (236±60) | 0.113 |

| BNP, n (pg/ml) | 254/254 (199±384) | 158/158 (194±377) | 96/96 (208±397) | 0.985 |

| LVEF, n (%) | 618/619 (59±11) | 370/371 (59±11) | 248/248 (59±10) | 0.998 |

| Vascular access | ||||

| Femoral, n (%) | 38/611 (6.2) | 19/364 (5.2) | 19/247 (7.7) | 0.214 |

| Radial, n (%) | 573/611 (93.8) | 345/364 (94.8) | 228/247 (92.3) | 0.214 |

| No. of diseased vessels | ||||

| 0, n (%) | 37/605 (6.1) | 22/361 (6.1) | 15/244 (6.1) | 0.979 |

| 1, n (%) | 300/605 (49.6) | 181/361 (50.1) | 119/244 (48.8) | 0.741 |

| 2, n (%) | 173/605 (28.6) | 106/361 (29.4) | 67/244 (27.5) | 0.611 |

| 3, n (%) | 95/605 (15.7) | 52/361 (14.4) | 43/244 (17.6) | 0.286 |

| Revascularization | ||||

| None, n (%) | 68/597 (11.4) | 45/357 (12.6) | 23/240 (9.6) | 0.255 |

| PCI,% | 518/597 (86.8) | 307/357 (86.0) | 211/240 (87.9) | 0.497 |

| CABG, n (%) | 9/597 (1.5) | 4/357 (1.1) | 5/240 (2.1) | 0.495 |

| PCI+CABG, n (%) | 2/597 (0.3) | 1/357 (0.3) | 1/240 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Other interventions | ||||

| IMV, n (%) | 5/619 (0.8) | 3/371 (0.8) | 2/248 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| NIMV, n (%) | 6/619 (1.0) | 2/371 (0.5) | 4/248 (1.6) | 0.225 |

BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; Cr: creatinine; Hb: hemoglobin; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NIVM: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

The timing of CA was the only significant difference between the groups (mean time 8±6 vs. 63±47 h, p<0.001). Although transradial access was preferred in both groups, it was more frequently used in the ES (94.8 vs. 92.3%, p=0.214). On CA, 6.1% had normal coronary arteries. Most patients in both groups presented single-vessel disease (49.6%), but there was also a high rate of multivessel disease (44.8%). No significant differences were observed between the groups regarding coronary anatomy burden or complexity (assessed through the number of diseased vessels and the presence of chronic occlusions). Medical therapy was proposed for 11.4% of patients. Coronary revascularization was performed in 88.6% of patients: PCI in 86.8%, CABG in 1.5% and both in 0.3%, with no significant differences between groups. Complete revascularization was performed in 71.8% and 69.3% patients in the ES and DS groups, respectively (p=0.538).

Table 3 presents relevant medication in-hospital and at discharge. Pending CA, 98.9% were medicated with aspirin. P2Y12 antagonists were initially administered during CA, mainly ticagrelor (66.0%) and clopidogrel (42.3%). There were no significant differences between the ES and DS groups regarding the chosen antiplatelet agent. Regarding anticoagulation strategies, patients proposed for an ES were more often medicated with unfractionated heparin (6.5 vs. 2.0%, p=0.010) and less with fondaparinux (56.6 vs. 64.9%, p=0.039). They were also more often medicated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during and/or after CA (37.3 vs. 28.3%, p=0.015). Lower percentages of calcium-channel blockers (11.7 vs. 25.2%, p=0.021) and nitrates (53.6 vs. 72.6%, p<0.001) were also observed in the ES. No difference was observed in beta-blocker use (p=0.820). Regarding discharge medication, the use of antiplatelet therapies, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists and statins did not differ between groups. The only observed difference was lower prescription rates of calcium channel blockers (11.5 vs. 18.9%, p=0.010) and nitrates (17.8 vs. 25.1%, p=0.028) in the ES.

In-hospital and discharge medication.

| Overall (n=619) | Early strategy (n=371) | Delayed strategy (n=248) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital medication, n (%) | ||||

| Aspirin | 612/619 (98.9) | 368/371 (99.2) | 244/248 (98.4) | 0.446 |

| Clopidogrel | 262/619 (42.3) | 161/371 (43.4) | 101/248 (40.7) | 0.510 |

| Prasugrel | 1/617 (0.2) | 1/371 (0.3) | 0/246 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Ticagrelor | 408/618 (66.0) | 244/370 (65.9) | 164/248 (66.1) | 0.962 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 208/617 (33.7) | 138/370 (37.3) | 70/247 (28.3) | 0.021 |

| UFH | 29/618 (4.7) | 24/371 (6.5) | 5/247 (2.0) | 0.010 |

| LMWH | 91/619 (14.7) | 47/371 (12.7) | 44/248 (17.7) | 0.081 |

| Fondaparinux | 371/619 (59.9) | 210/317 (56.6) | 161/248 (64.9) | 0.039 |

| VKA | 5/619 (0.8) | 1/371 (0.3) | 4/248 (1.6) | 0.163 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 19/619 (3.1) | 15/371 (4.0) | 4/248 (1.6) | 0.117 |

| Beta-blocker | 492/619 (79.5) | 296/371 (79.8) | 196/248 (79.0) | 0.820 |

| Nitrates | 379/619 (61.2) | 199/371 (53.6) | 180/248 (72.6) | <0.001 |

| CCBs | 97/619 (15.7) | 42/371 (11.3) | 55/248 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics | 98/619 (15.8) | 53/371 (14.3) | 45/248 (18.1) | 0.197 |

| Discharge medication, n (%) | ||||

| Aspirin (%) | 598/609 (98.2) | 358/366 (97.8) | 240/243 (98.8) | 0.539 |

| Clopidogrel | 208/609 (34.2) | 122/366 (33.3) | 86/243 (35.4) | 0.600 |

| Prasugrel | 4/608 (0.7) | 4/366 (1.1) | 0/242 (0.0) | 0.155 |

| Ticagrelor | 376/609 (61.7) | 226/366 (61.7) | 150/243 (61.7) | 0.996 |

| VKA | 5/609 (0.8) | 2/366 (0.5) | 3/243 (1.2) | 0.393 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 39/609 (6.4) | 27/366 (7.3) | 12/243 (4.9) | 0.512 |

| ACEIs/ARBs | 511/609 (83.9) | 304/366 (83.1) | 207/243 (85.2) | 0.485 |

| Beta-blockers | 481/609 (79.0) | 292/366 (79.8) | 189/243 (77.8) | 0.552 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 38/609 (6.2) | 25/366 (6.8) | 13/243 (5.3) | 0.459 |

| Statins | 589/609 (96.7) | 351/366 (95.9) | 238/243 (97.9) | 0.166 |

| Nitrates | 126/609 (20.7) | 65/366 (17.8) | 61/243 (25.1) | 0.028 |

| CCBs (%) | 88/609 (14.4) | 42/366 (11.5) | 46/243 (18.9) | 0.010 |

ACEIs/ARBs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers; CCBs: calcium channel blockers; GP: glycoprotein; LMWH: low molecular weight heparin; UFH: unfractionated heparin; VKA: vitamin K antagonist.

Adverse in-hospital outcomes (Table 4) were not significantly different between groups, except for major bleeding, which was less prevalent in the ES (0.3 vs. 2.0%, p=0.041). Only one patient presented major bleeding in the ES, located in the urinary tract. Five patients in the DS presented with major bleeding: four vascular access-related and one from the bowel. There was a trend toward better outcomes in the ES group regarding heart failure (6.7 vs. 7.7%, p=0.662), shock (0.5 vs. 0.4%, p=1.000), ventricular arrhythmias (0.3 vs. 0.4%, p=1.000), cardiac arrest (1.3 vs. 2.4%, p=0.362), transfusion need (0.3 vs. 1.6%, p=163) and death (0 vs. 0.4%, p=0.401).

Adverse outcomes during hospitalization.

| Overall (n=619) | Early strategy (n=371) | Delayed strategy (n=248) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 5/619 (0.8) | 4/4371 (1.1) | 1/248 (0.4) | 0.653 |

| HF, n (%) | 44/619 (7.1) | 25/371 (6.7) | 19/248 (7.7) | 0.662 |

| Shock, n (%) | 3/619 (0.5) | 2/371 (0.5) | 1/248 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| AF, n (%) | 16/619 (2.6) | 9/371 (2.4) | 7/248 (2.8) | 0.761 |

| SVT, n (%) | 2/619 (0.3) | 1/371 (0.3) | 1/248 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 11/619 (1.8) | 5/371 (1.3) | 6/248 (2.4) | 0.362 |

| Major bleeding, n (%) | 6/619 (1.0) | 1/371 (0.3) | 5/248 (2.0) | 0.041 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 5/619 (0.8) | 1/371 (0.3) | 4/248 (1.6) | 0.163 |

| Death, n (%) | 1/619 (0.2) | 0/371 (0.0) | 1/248 (0.4) | 0.401 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; HF: heart failure; SVT: sustained ventricular tachycardia.

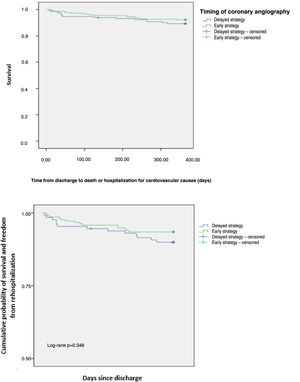

The one-year composite endpoint of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 8.9% in the overall population, with no difference between groups (p=0.348) (Figure 1). Individual endpoints were also not statistically different: rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 7.7% (p=0.278) and all-cause mortality in 2.8% (p=0.882). An ES was not associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes (hazard ratio [HR] 0.612, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.256-1.466, p=0.138). Previous PCI (adjusted HR 3.215, 95% CI 1.323-7.811, p=0.010), previous stroke/transient ischemic attack (adjusted HR 6.040, 95% CI 1.752-20.818, p=0.004), Killip class >I (adjusted HR 14.507, 95% CI 3.02-20.62, p<0.001), nitrate prescription at discharge (adjusted HR 2.385, 95% CI 3.28-68.79, p<0.001) and in-hospital major bleeding (adjusted HR 14.556, 95% CI 1.488-142.436, p=0.021) were independent predictors of the one-year composite endpoint (Table 5). Variables associated with the endpoint in the univariate analysis (p<0.05) were included in the final multivariate analysis.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for potential predictors of the primary endpoint, a composite of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes at one year.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Early vs. delayed strategy | 0.612 | 0.256-1.466 | 0.138 | - | - | - |

| Age | 1.032 | 1.003-1.061 | 0.029 | 0.045 | - | 0.964 |

| Gender | 1.218 | 0.571-2.600 | 0.610 | - | - | - |

| Hypertension | 3.551 | 1.378-9.153 | 0.009 | 0.079 | - | 0.157 |

| Previous PCI | 2.991 | 1.436-6.228 | 0.033 | 3.215 | 1.323-7.811 | 0.010 |

| Previous CABG | 3.030 | 0.928-9.896 | 0.066 | - | - | - |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 4.440 | 1.722-11.445 | 0.002 | 6.040 | 1.752-20.818 | 0.004 |

| Heart failure | 3.724 | 1.140-12.166 | 0.029 | 0.002 | - | 0.982 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4.875 | 5.167-20.355 | 0.030 | 0.002 | - | 0.968 |

| Heart rate | 1.018 | 1.000-1.037 | 0.054 | - | - | - |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.998 | 0.985-1.011 | 0.759 | - | - | - |

| Killip class >I | 9.453 | 4.627-19.311 | <0.001 | 14.507 | 3.02-20.62 | <0.001 |

| Maximum creatinine | 1.478 | 1.117-1.955 | 0.006 | 0826 | - | 0.363 |

| Minimum hemoglobin | 0.712 | 0.377-1.343 | 0.294 | - | - | - |

| BNP level | 1.001 | 1.000-1.002 | 0.013 | 0.187 | - | 0.413 |

| In-hospital UFH | 2.515 | 0.770-8.213 | 0.127 | - | - | - |

| In-hospital GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 1.369 | 0.704-2.661 | 0.355 | - | - | - |

| In-hospital fondaparinux | 0.451 | 0.229-0.87 | 0.021 | 2.763 | - | 0.273 |

| In-hospital nitrates | 1.823 | 0.875-3.795 | 0.109 | - | - | - |

| Nitrates at discharge | 3.696 | 1.868-7.316 | <0.001 | 2.385 | 3.28-68.79 | <0.001 |

| Femoral vascular access | 0.242 | 0.100-0.585 | 0.002 | 0.421 | - | 0.158 |

| Complete revascularization | 0.141-0.658 | 0.003 | 1.168 | - | 0.262 | |

| LVEF <50% | 2.950 | 1.445-6.022 | 0.003 | 0.056 | - | 0.633 |

| In-hospital reinfarction | 0.049 | 0.001-1366.74 | 0.049 | 0.096 | - | 0.757 |

| In-hospital major bleeding | 3.008 | 0.412-21.983 | 0.015 | 14.556 | 1.488-142.436 | 0.021 |

| In-hospital heart failure | 7.236 | 3.389-15.448 | <0.001 | 0.791 | - | 0.388 |

BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CI: confidence interval; GP: glycoprotein; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA: transient ischemic attack; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

The importance of our study is related to the significant worldwide burden of NSTE-ACS, which arises not only from the index hospitalization but also from patients’ worse mid- and long-term prognosis compared with ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome, with more frequent recurrent ischemic events and a twofold higher death rate at two years.11

In our study, we observed a trend toward an ES in younger patients with lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease, lower Killip class, lower creatinine and higher hemoglobin levels. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding coronary anatomy burden or complexity (assessed through the number of diseased vessels and the presence of chronic occlusions). There were no significant differences regarding antiplatelet therapy during hospitalization. The major difference observed was a lower percentage of anti-ischemic therapy in the ES, both during hospitalization and at discharge. Despite a trend toward fewer adverse in-hospital outcomes in the ES, only major bleeding was statistically significant, and this did not affect one-year outcomes.

The European guidelines recommend timing coronary intervention depending on the patient's baseline risk.3,8 An earlier approach provides a rapid diagnosis and mechanical revascularization and shorter hospital stays, despite a potential hazard because of unstable plaques with fresh thrombus. Conversely, a delayed strategy may provide benefits through plaque passivation by optimal medical treatment followed by intervention on more stable plaques, despite a higher risk for events while awaiting intervention.3

The initial phase and evolution of NSTE-ACS is marked by activation of blood platelets and the coagulation cascade, so adequate platelet inhibition and anticoagulation is desirable, especially in patients undergoing PCI.8 According to recent literature, routine PT no longer appears to be appropriate in NSTE-ACS due to an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio, so it is not recommended in patients in whom the coronary anatomy is unknown and an ES is planned.8,9,11–15 For patients with a DS, PT with a P2Y12 antagonist may be considered in selected cases according to the patient's bleeding risk.8 The rationale behind PT was to provide maximum inhibition of platelet aggregation while patients are waiting to undergo CA and to reduce thrombotic complications at the time of PCI, given that even the fastest-acting oral P2Y12 antagonists take at least 30-60 min to achieve maximum platelet inhibition, by which time most PCI procedures have already been completed.1,6–8 In fact, in our study, 11.4% patients were proposed for medical therapy, 1.5% for CABG and 6.1% had normal coronary arteries. In cases in which PT is not administered, patients are not protected pending the invasive procedure and may experience recurrent ischemic events and/or complications, so the optimal timing of the invasive strategy in this specific context is unknown. In our study, we excluded all patients with PT, independently of CA timing. There were no significant differences regarding antiplatelet therapies during hospitalization. Of note, the total number of patients taking each of the P2Y12 inhibitors is higher than 100%, as patients may have switched between two agents during hospitalization. Regarding anticoagulant therapies, the only statistically significant difference was that patients proposed for an ES were more often medicated with unfractionated heparin and less often with fondaparinux, which was to be expected due to the need for constant monitoring of therapeutic values of heparin.

The stipulated timings for coronary intervention are supported by two large trials. The Timing of Intervention in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes (TIMACS) and the Very Early Versus Deferred Invasive Evaluation Using Computerized Tomography (VERDICT) trials showed that an ES was not superior to a DS with regard to composite clinical endpoints in NSTE-ACS patients, except for the highest GRACE risk score tertile.1,2,8 Although the mean GRACE score was similar between groups, patients proposed for an ES were younger, with less CKD, and tended to have lower creatinine levels and Killip class, so we can infer that in the DS group, CA was delayed until clinical stabilization, which is in accordance with an observed trend for higher use of diuretics and ventilatory support in this group, or alternatively to patient optimization to prevent contrast nephropathy. Individual trials and meta-analyses were underpowered to detect individual clinical endpoints such as mortality, non-fatal MI or stroke; only recurrent or refractory ischemia and length of hospital stay have been shown to be improved by an ES.2,8,11,16 The LIPSIA-NSTEMI trial concluded that an immediate invasive approach did not offer an advantage over an early (10-48 h) or a selective invasive approach with respect to infarct size as defined by peak CK-MB levels.17 The RIDDLE-NSTEMI trial showed that an immediate invasive strategy was associated with lower rates of death or new MI compared with a delayed (2-72 h) strategy at 30-day follow-up, mainly due to a decrease in the risk of new MI in the pre-intervention period. In one-year follow-up, the rates of death, new MI and recurrent ischemia were similar. At both 30 days and one year, the rates of major bleeding were similar in both groups.18 In our study, adverse in-hospital outcomes were not significantly different between groups, except for major bleeding, which was less prevalent in the ES. In this group, although not statistically significant, transfemoral access, which is known to be associated with more bleeding complications, was used in a lower proportion of patients.8 Even so, in the ACCOAST trial transfemoral access did not significantly increase major bleeding, but transradial access was associated with a reduction in major or minor bleeding.19 Also, patients proposed for an ES presented lower creatinine and higher hemoglobin levels at admission and during hospitalization. The choice and dose of antithrombotic drugs should be carefully considered in patients with kidney dysfunction, as these patients have an increased risk of bleeding. Anemia is also associated with increased mortality, recurrent MI and major bleeding.8 There was a trend toward worse outcomes in the DS group regarding heart failure, shock, ventricular arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, transfusion need and death, which is not surprising since these complications could be associated with delayed revascularization and a greater need for blood transfusion, since these patients more often presented with major bleeding. These endpoints were not individually assessed in previous studies except for heart failure, which, as in our study, showed a trend toward less heart failure hospitalization in favor of an ES (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60-1.01) in the VERDICT trial.4 However, these outcomes were not reflected in the one-year individual or composite endpoints of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes, as also shown in previous studies.1,2 In our study, a major difference was observed regarding the higher percentage of anti-ischemic therapy in the DS, namely calcium-channel blockers and nitrates, since the most important concern related to DS is reinfarction and angina recurrence.1,2,4 No difference was observed in beta-blocker use since in clinical practice they are used more often as a neurohormonal therapy rather than as an anti-ischemic, and were thus used similarly in both groups. Discharge medication followed the above-presented trends. The use of antiplatelet, neurohormonal and secondary prevention therapies did not differ between groups, which is also in accordance with a similar mean LVEF between groups. A higher prescription rate of anti-ischemic therapies was observed, following the trend of hospitalization prescription. Although not statistically significant, a higher percentage of incomplete revascularization was observed in the DS, possibly explaining this higher prescription rate.

In the EARLY trial, the only study comparing the two invasive strategies in patients with intermediate- and high-risk NSTE-ACS without PT, a very early (<2 h) versus delayed (12-72 h) invasive strategy was associated with a lower rate of the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death and recurrent ischemic events requiring urgent revascularization, due to a lower rate of total occlusion of the culprit artery at the time of CA. Both strategies had similar safety in terms of bleeding events.9,11 We recognize that the stipulated CA timings were significantly different from those in our study, but we agree there is no advantage in ES regarding mortality, and we cannot properly assess recurrent ischemia since we did not stipulate this single endpoint. In our study, an ES (<24 h) was favored in less complex patients but was not associated with a reduction in adverse in-hospital outcomes except for major bleeding. We assume this may be related to higher hemoglobin levels at admission and during hospitalization and lower use of transfemoral access, although it did not translate into a greater need for blood transfusion or higher mortality. Based on our results, we cannot suggest that delaying CA might be harmful in our patient cohort.

Our study presents some limitations. First, it is a retrospective observational study and thus susceptible to inherent limitations including missing data, partucilarly related to follow-up. Since this is a voluntary registry, it does not represent all the cardiology centers in the country and, even in the centers that do participate, we cannot guarantee that all patients are included. Second, our sample is not large, since we had to exclude many patients who were medicated with PT, reflecting the guidelines of that time. Third, we do not know the proportion of very high-risk patients in our population who could have benefited from an immediate approach. Fourth, there are confounding factors that guided the timing of CA, especially whether the hospital had a catheterization laboratory and if so, whether it was available. Fifth, there were no data regarding adherence to medical treatment after discharge that could influence outcomes, and we were unable to properly assess recurrence of ischemic events.

ConclusionsIn patients with higher-risk NSTE-ACS in the absence of PT with a P2Y12 antagonist, an early invasive strategy was not associated with higher in-hospital adverse outcomes or a reduction in the composite of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes at one year.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.