Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a complex condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach. It is crucial that adults with CHD (CHD) have adequate knowledge of their condition, enabling them to engage in their healthcare decisions and self-management. We aimed to investigate knowledge and perception among adults of their CHD.

MethodsSingle-center, observational, cross-sectional study. A 25-item adapted survey of Leuven Questionnaire for CHD was used to assess four main domains: (1) disease and treatment, (2) endocarditis and preventive measures, (3) physical activity and (4) reproductive issues.

ResultsOne hundred forty-eight patients participated in the study. Patients had a significant lack of knowledge localizing their heart defect, recognizing drug side effects, acting in case of experiencing drug side effects, recognizing at least two symptoms of clinical deterioration, to adequately define endocarditis and most typical signs and risk factors, to acknowledge the hereditary nature of their CHD and risk of clinical deterioration during pregnancies. Patients with an education level ≥12th grade have higher knowledge in various items and, overall, the complexity of CHD was not associated with a better performance.

ConclusionThis study highlights the existing knowledge gaps among adults with CHD. It underscores the need for tailored information and structured educational programs to improve management. By addressing these challenges, healthcare providers can enhance patient outcomes, improve quality of life, and promote long-term well-being for individuals with CHD.

A cardiopatia congénita é uma doença complexa que requer uma abordagem multidisciplinar. É crucial que os doentes adultos com cardiopatia congénita possuam um conhecimento adequado sobre a sua doença, capacitando-os para se envolverem no autocuidado e decisões relacionadas com a saúde. O nosso objetivo foi investigar o conhecimento e perceção de adultos sobre a sua cardiopatia congénita.

MétodosEstudo unicêntrico, observacional e transversal. Foi utilizado um questionário de 25-itens adaptado a partir do Leuven Questionnaire for Congenital Heart Disease, para avaliar quatro domínio principais: (1) doença e tratamento, (2) endocardite e medidas preventivas, (3) atividade física e (4) questões reprodutivas.

ResultadosParticiparam no estudo 148 doentes. Os participantes tiveram uma significativa falta de conhecimento na localização do seu defeito cardíaco, em reconhecer e como agir no caso de experienciar efeitos adversos da medicação, no reconhecimento de pelo menos dois sintomas de deterioração clínica, na definição adequada de endocardite bem como dos principais sintomas e fatores de risco da doença, no reconhecimento da natureza hereditária da sua cardiopatia e do potencial risco de deterioração clínica durante a gravidez. Doentes com um nível de educação ≥12°. Ano têm um maior nível de conhecimento em vários itens e, de forma geral, a complexidade da cardiopatia não está associada a uma melhor performance.

ConclusãoEste estudo enaltece as falhas de conhecimento existentes entre adultos com cardiopatia congénita. Sublinha a necessidade de informação personalizada e programas educativos estruturados para melhorar o cuidado destes doentes. Ao enfrentar estes desafios, os profissionais de saúde poderão aumentar os resultados clínicos dos doentes, melhorar a qualidade de vida e promover um bem-estar duradouro entre os indivíduos com cardiopatia congénita.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a complex condition that requires specialized structural and organizational healthcare systems to effectively address the unique needs of these patients.1 In recent decades, advancements in medical care and improved treatment strategies have led to a growing number of individuals with CHD reaching adulthood.2–4

Currently, global prevalence of CHD is approximately 9 per 1000 births with geographical variation.5,6 In Portugal, prevalence ranges between 5 and 8 per 1000 newborns, according to data from the National Register of Congenital Anomalies.7

Healthcare management of these patients is complex, requiring a multidisciplinary approach, from adult and pediatric congenital cardiologists, imaging specialists, interventional congenital cardiologists and CHD surgeons to specialist nurses, psychologists, social workers, and palliative care team, among others.1,8

It is crucial for these patients to possess adequate knowledge and understanding of their condition, enabling them to actively engage in their healthcare decisions and participate in self-management. The few studies focusing on transfer to adult care or adult patients with CHD have demonstrated significant knowledge gaps in various major disease domains, such as disease and treatment-relate, endocarditis-related and physical- and reproductive-related issues.9,10

Furthermore, in a small observational study, Goossens et al. demonstrated an improvement in total knowledge of patients that participated in an educational session compared to those who did not. Still, this type of education did not improve patient's tendency to engage in better health behaviors.11

Also, Ladouceur et al. conducted a study demonstrating that the implementation of a structured educational program during the transition from pediatric to adult care resulted in a significant improvement in health knowledge among patients.12

ObjectivesIn the present study we aimed to investigate knowledge and perception among adults of their CHD. We sought to further analyze the association between the level of education and complexity of CHD with correct CHD knowledge.

MethodsStudy designThis was an observational, descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in tertiary ACHD care center. Consecutive patients with CHD were opportunistically recruited to participate in the study at their CHD medical visit, between CHD heart disease, had regular clinical follow-up by the adult CHD team at our center and provided informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had any cognitive or physical disabilities that impaired the provision of adequate responses to the survey.

Clinical and demographic data were collected at study inclusion from patient interviews and electronic medical records.

Leuven Knowledge QuestionnairePatients’ CHD knowledge and perception was assessed using the Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire (LKQ) for CHD, developed in 2001.9 The authors translated and adapted the LKQ for CHD to Portuguese, as it was validated elsewhere.13

The survey includes 25 items that cover four main domains: (1) disease and treatment, (2) endocarditis and preventive measures, (3) physical activity and (4) reproductive issues. Patient's answers were classified as “correct”, “incorrect”, “does not know”, “did not answer” and “incomplete”.

Upon for their scheduled outpatient medical visit for the adult CHD program, patients were opportunistically asked by a physician or a nurse to participate in the study. The study objectives and protocol were explained to the patients. Once they had provided informed consent, the LKQ for CHD was completed before entering the physician's room in the designated area. Patients were given 15–30 minutes to complete the survey, as required. Patients were encouraged to answer the questions in the best way they were able. When the patients entered the consultation room, the responsible physician collected the questionnaire, and no further modification of the answers was permitted. Afterwards, suitable patient education was provided by the dedicated physician. Data were introduced in an Excel® spreadsheet.

Statistical analysisFor the primary descriptive analysis, categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables as means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges as appropriate. Normal distribution was checked using Shapiro–Wilk test.

For the secondary analysis to assess the association between demographic variables of interest and CHD knowledge, further reclassification into dichotomized variables was performed. Demographic variables of interest were categorized as follows: (1) highest education level into ≥12th grade or <12th grade, the first including “12th grade”, “undergraduate degree”, “master degree”, “PhD degree” and “other” and the latter including “4th grade and “9th grade”; (2) complexity of CHD into “severe” or “non-severe”, the latter including “mild” and “moderate”. Knowledge variables were categorized as “correct” and “not correct”, the latter including the “incorrect”, “does not know”, “did not answer” and “incomplete answers”.

A Chi-Square or Fisher exact test was performed for statistical purposes. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. All reported p values are two-tailed, with a reported p value <0.05 indicating statistical significance. Data were analyzed in IBM SPSS Statistics® (version 26).

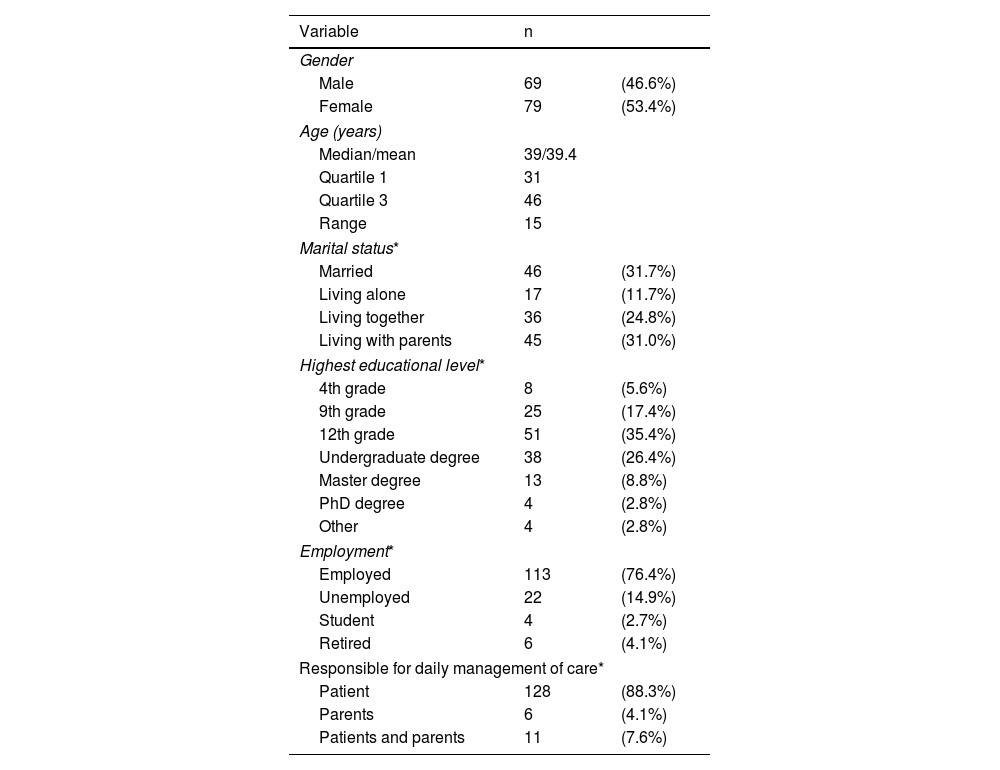

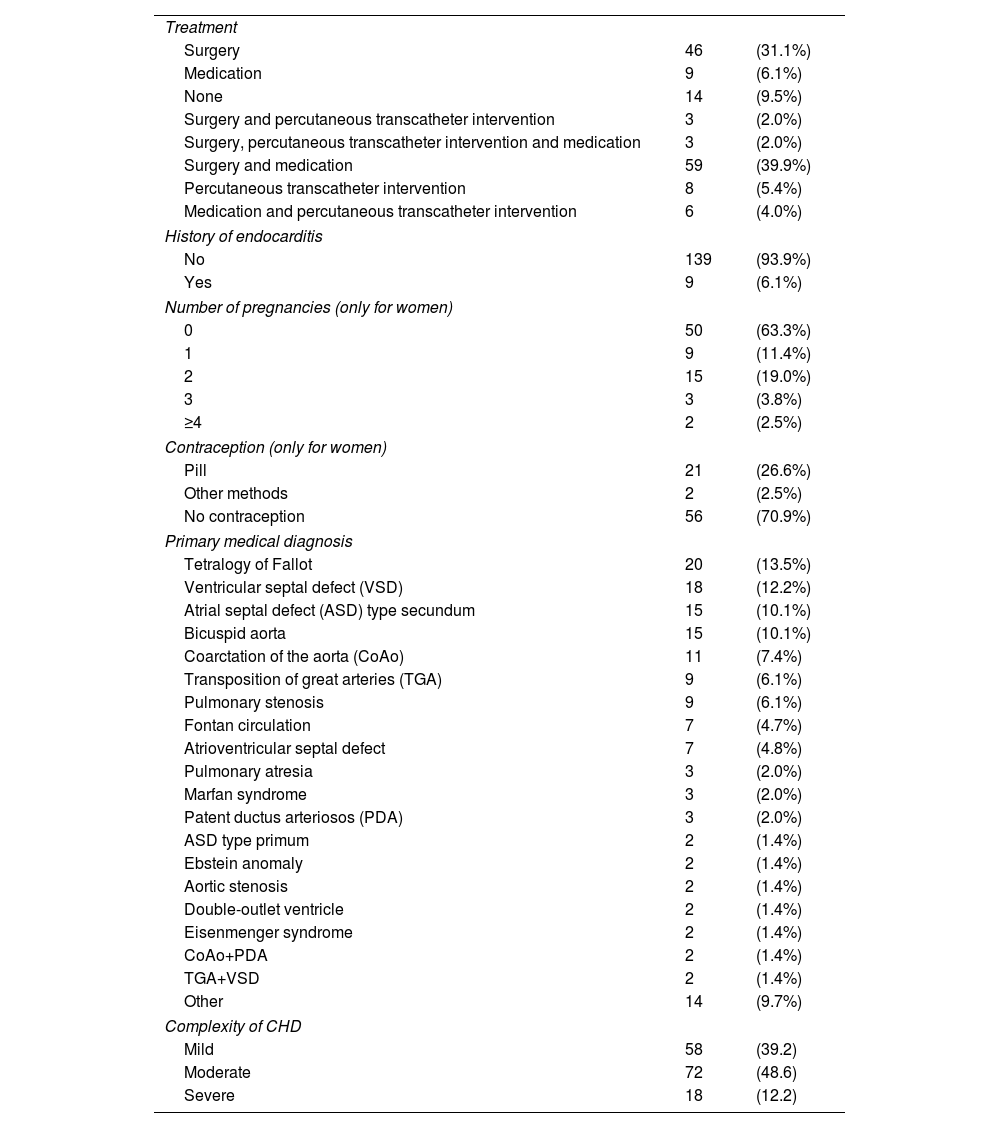

ResultsFrom a total of 1124 patients observed during the recruitment period, 148 were invited and agreed to participate in the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The median age was 39 years and 53.4% were female. 82 (55.4%) patients were married or living together with a partner, 110 (74.3%) patients had an education equal to or above 12th grade and 113 (76.4%) were employed. Most patients (88.3%) were responsible for their daily care management. Regarding treatment, 111 (75%) patients had previous cardiac surgery, 20 (13.5%) had previous percutaneous transcatheter interventions and 77 (52%) patients are currently on cardiovascular medication. Only 15 (10.1%) had neither intervention nor cardiovascular medication. Nine (6.1%) patients had a previous history of endocarditis. Most women (63.3%) had not been pregnant previously and 2 (2.4%) had had at least four pregnancies. Fifty-six (70.9%) women did not use contraception and 21 (26.6%) took a birth control pill.

Demographic characteristics of 148 adults with congenital heart disease (CHD).

| Variable | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 69 | (46.6%) |

| Female | 79 | (53.4%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median/mean | 39/39.4 | |

| Quartile 1 | 31 | |

| Quartile 3 | 46 | |

| Range | 15 | |

| Marital status* | ||

| Married | 46 | (31.7%) |

| Living alone | 17 | (11.7%) |

| Living together | 36 | (24.8%) |

| Living with parents | 45 | (31.0%) |

| Highest educational level* | ||

| 4th grade | 8 | (5.6%) |

| 9th grade | 25 | (17.4%) |

| 12th grade | 51 | (35.4%) |

| Undergraduate degree | 38 | (26.4%) |

| Master degree | 13 | (8.8%) |

| PhD degree | 4 | (2.8%) |

| Other | 4 | (2.8%) |

| Employment* | ||

| Employed | 113 | (76.4%) |

| Unemployed | 22 | (14.9%) |

| Student | 4 | (2.7%) |

| Retired | 6 | (4.1%) |

| Responsible for daily management of care* | ||

| Patient | 128 | (88.3%) |

| Parents | 6 | (4.1%) |

| Patients and parents | 11 | (7.6%) |

Clinical characteristics of 148 adults with congenital heart disease (CHD).

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery | 46 | (31.1%) |

| Medication | 9 | (6.1%) |

| None | 14 | (9.5%) |

| Surgery and percutaneous transcatheter intervention | 3 | (2.0%) |

| Surgery, percutaneous transcatheter intervention and medication | 3 | (2.0%) |

| Surgery and medication | 59 | (39.9%) |

| Percutaneous transcatheter intervention | 8 | (5.4%) |

| Medication and percutaneous transcatheter intervention | 6 | (4.0%) |

| History of endocarditis | ||

| No | 139 | (93.9%) |

| Yes | 9 | (6.1%) |

| Number of pregnancies (only for women) | ||

| 0 | 50 | (63.3%) |

| 1 | 9 | (11.4%) |

| 2 | 15 | (19.0%) |

| 3 | 3 | (3.8%) |

| ≥4 | 2 | (2.5%) |

| Contraception (only for women) | ||

| Pill | 21 | (26.6%) |

| Other methods | 2 | (2.5%) |

| No contraception | 56 | (70.9%) |

| Primary medical diagnosis | ||

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 20 | (13.5%) |

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) | 18 | (12.2%) |

| Atrial septal defect (ASD) type secundum | 15 | (10.1%) |

| Bicuspid aorta | 15 | (10.1%) |

| Coarctation of the aorta (CoAo) | 11 | (7.4%) |

| Transposition of great arteries (TGA) | 9 | (6.1%) |

| Pulmonary stenosis | 9 | (6.1%) |

| Fontan circulation | 7 | (4.7%) |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | 7 | (4.8%) |

| Pulmonary atresia | 3 | (2.0%) |

| Marfan syndrome | 3 | (2.0%) |

| Patent ductus arteriosos (PDA) | 3 | (2.0%) |

| ASD type primum | 2 | (1.4%) |

| Ebstein anomaly | 2 | (1.4%) |

| Aortic stenosis | 2 | (1.4%) |

| Double-outlet ventricle | 2 | (1.4%) |

| Eisenmenger syndrome | 2 | (1.4%) |

| CoAo+PDA | 2 | (1.4%) |

| TGA+VSD | 2 | (1.4%) |

| Other | 14 | (9.7%) |

| Complexity of CHD | ||

| Mild | 58 | (39.2) |

| Moderate | 72 | (48.6) |

| Severe | 18 | (12.2) |

ASD: atrial septal defect; CHD: congenital heart disease; CoAo: coarctation of the aorta; PDA: patent ductus arteriosus; TGA: transposition of great arteries; VSD: ventricular septal defect.

The most five prevalent primary diagnosis (Table 1) were Tetralogy of Fallot (13.5%), ventricular septal defect (12.2%), ostium secundum atrial septal defect type (10.1%), bicuspid aortic valve (10.1%) and coarctation of the aorta (7.4%). Regarding the complexity of CHD, 18 (12.2%) were classified as severe, according to European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the management of adult CHD.1

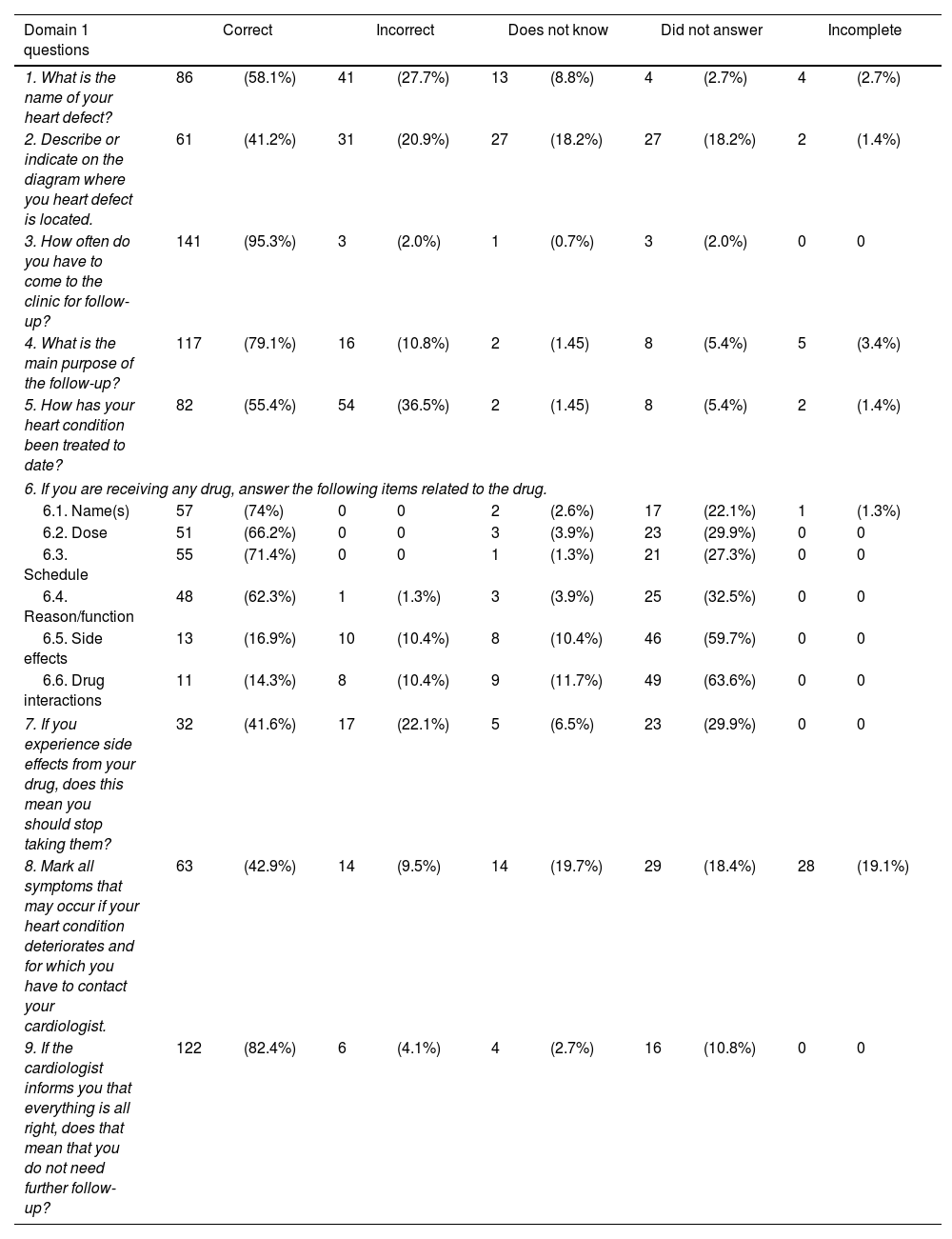

Table 3 depicts patients’ knowledge about their disease and treatment. More than half patients (58.1%) knew the name of their CHD and 41.2% could describe or locate the lesion on the pictured diagram. Most patients could tell the main purpose for follow-up was to detect clinical deterioration and had adequate knowledge about previous treatments. Only 42.9% were able to identify at least two symptoms of clinical deterioration of their heart disease, such as chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, fainting, palpitations, excessive fatigue or swollen legs or feet. Most patients knew they should keep further follow-up even if the condition is considered stable.

Frequency of patients’ knowledge about their disease and treatment (n=148).

| Domain 1 questions | Correct | Incorrect | Does not know | Did not answer | Incomplete | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. What is the name of your heart defect? | 86 | (58.1%) | 41 | (27.7%) | 13 | (8.8%) | 4 | (2.7%) | 4 | (2.7%) |

| 2. Describe or indicate on the diagram where you heart defect is located. | 61 | (41.2%) | 31 | (20.9%) | 27 | (18.2%) | 27 | (18.2%) | 2 | (1.4%) |

| 3. How often do you have to come to the clinic for follow-up? | 141 | (95.3%) | 3 | (2.0%) | 1 | (0.7%) | 3 | (2.0%) | 0 | 0 |

| 4. What is the main purpose of the follow-up? | 117 | (79.1%) | 16 | (10.8%) | 2 | (1.45) | 8 | (5.4%) | 5 | (3.4%) |

| 5. How has your heart condition been treated to date? | 82 | (55.4%) | 54 | (36.5%) | 2 | (1.45) | 8 | (5.4%) | 2 | (1.4%) |

| 6. If you are receiving any drug, answer the following items related to the drug. | ||||||||||

| 6.1. Name(s) | 57 | (74%) | 0 | 0 | 2 | (2.6%) | 17 | (22.1%) | 1 | (1.3%) |

| 6.2. Dose | 51 | (66.2%) | 0 | 0 | 3 | (3.9%) | 23 | (29.9%) | 0 | 0 |

| 6.3. Schedule | 55 | (71.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (1.3%) | 21 | (27.3%) | 0 | 0 |

| 6.4. Reason/function | 48 | (62.3%) | 1 | (1.3%) | 3 | (3.9%) | 25 | (32.5%) | 0 | 0 |

| 6.5. Side effects | 13 | (16.9%) | 10 | (10.4%) | 8 | (10.4%) | 46 | (59.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| 6.6. Drug interactions | 11 | (14.3%) | 8 | (10.4%) | 9 | (11.7%) | 49 | (63.6%) | 0 | 0 |

| 7. If you experience side effects from your drug, does this mean you should stop taking them? | 32 | (41.6%) | 17 | (22.1%) | 5 | (6.5%) | 23 | (29.9%) | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Mark all symptoms that may occur if your heart condition deteriorates and for which you have to contact your cardiologist. | 63 | (42.9%) | 14 | (9.5%) | 14 | (19.7%) | 29 | (18.4%) | 28 | (19.1%) |

| 9. If the cardiologist informs you that everything is all right, does that mean that you do not need further follow-up? | 122 | (82.4%) | 6 | (4.1%) | 4 | (2.7%) | 16 | (10.8%) | 0 | 0 |

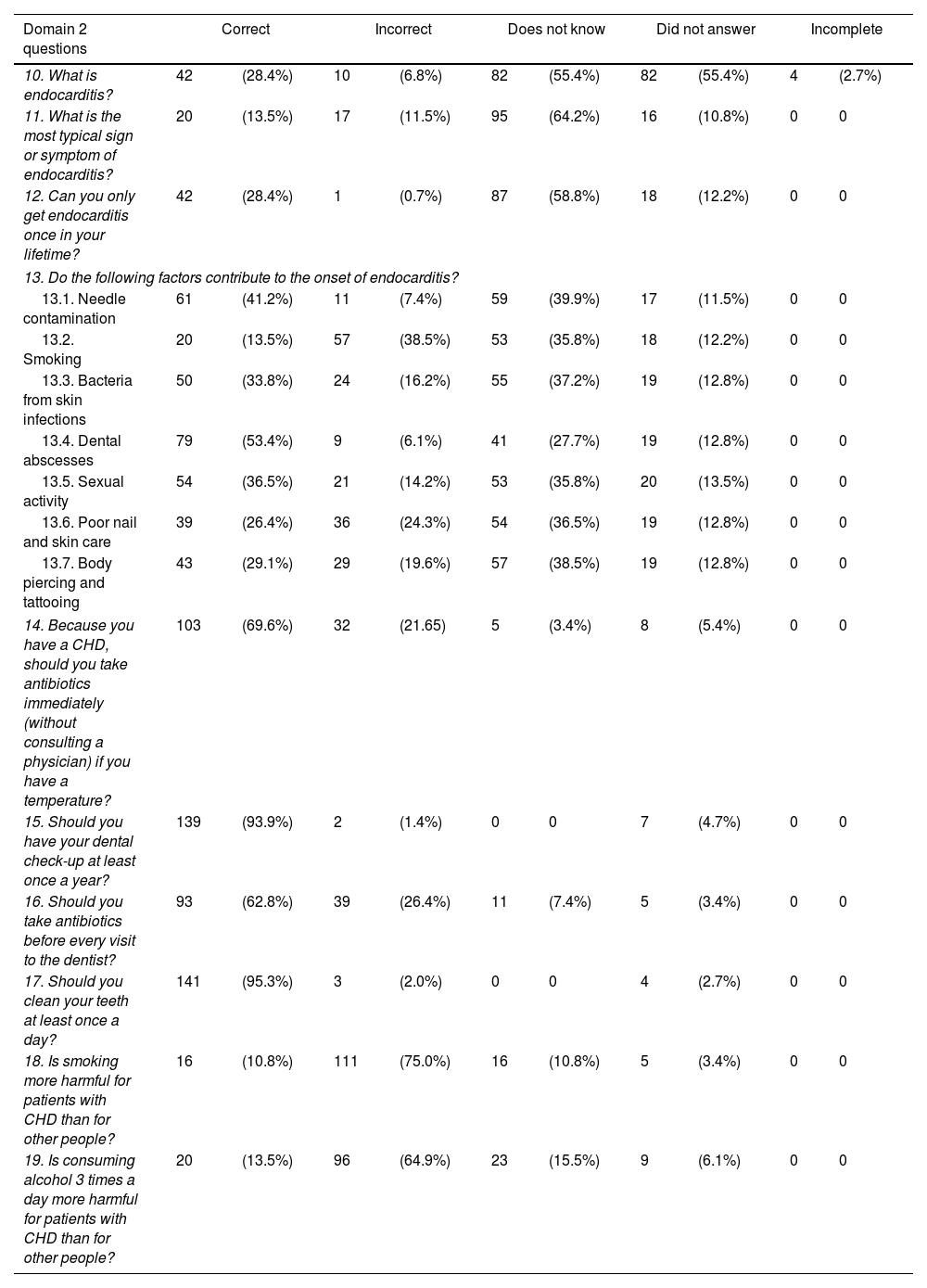

Knowledge regarding domain two about endocarditis and preventive measures is illustrated in Table 4. Only 42 (28.4%) patients could adequately describe what endocarditis is and 20 (13.5%) patients were able to identify fever as the most typical symptom of endocarditis. Most patients did not know the risk factors for endocarditis, including needle contamination (58.8%), skin infection (66.2%), dental abscess (46.6%), poor nail and skin care (73.6%), body piercing and tattooing (70.9%). Twenty (13.5%) and 54 (36.5%) patients incorrectly identified smoking and sexual activity as a risk factor for endocarditis, respectively. Adequate knowledge regarding dental practice was observed.

Frequency of patients’ knowledge about preventive measures (n=148).

| Domain 2 questions | Correct | Incorrect | Does not know | Did not answer | Incomplete | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10. What is endocarditis? | 42 | (28.4%) | 10 | (6.8%) | 82 | (55.4%) | 82 | (55.4%) | 4 | (2.7%) |

| 11. What is the most typical sign or symptom of endocarditis? | 20 | (13.5%) | 17 | (11.5%) | 95 | (64.2%) | 16 | (10.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| 12. Can you only get endocarditis once in your lifetime? | 42 | (28.4%) | 1 | (0.7%) | 87 | (58.8%) | 18 | (12.2%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13. Do the following factors contribute to the onset of endocarditis? | ||||||||||

| 13.1. Needle contamination | 61 | (41.2%) | 11 | (7.4%) | 59 | (39.9%) | 17 | (11.5%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13.2. Smoking | 20 | (13.5%) | 57 | (38.5%) | 53 | (35.8%) | 18 | (12.2%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13.3. Bacteria from skin infections | 50 | (33.8%) | 24 | (16.2%) | 55 | (37.2%) | 19 | (12.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13.4. Dental abscesses | 79 | (53.4%) | 9 | (6.1%) | 41 | (27.7%) | 19 | (12.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13.5. Sexual activity | 54 | (36.5%) | 21 | (14.2%) | 53 | (35.8%) | 20 | (13.5%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13.6. Poor nail and skin care | 39 | (26.4%) | 36 | (24.3%) | 54 | (36.5%) | 19 | (12.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| 13.7. Body piercing and tattooing | 43 | (29.1%) | 29 | (19.6%) | 57 | (38.5%) | 19 | (12.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| 14. Because you have a CHD, should you take antibiotics immediately (without consulting a physician) if you have a temperature? | 103 | (69.6%) | 32 | (21.65) | 5 | (3.4%) | 8 | (5.4%) | 0 | 0 |

| 15. Should you have your dental check-up at least once a year? | 139 | (93.9%) | 2 | (1.4%) | 0 | 0 | 7 | (4.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| 16. Should you take antibiotics before every visit to the dentist? | 93 | (62.8%) | 39 | (26.4%) | 11 | (7.4%) | 5 | (3.4%) | 0 | 0 |

| 17. Should you clean your teeth at least once a day? | 141 | (95.3%) | 3 | (2.0%) | 0 | 0 | 4 | (2.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| 18. Is smoking more harmful for patients with CHD than for other people? | 16 | (10.8%) | 111 | (75.0%) | 16 | (10.8%) | 5 | (3.4%) | 0 | 0 |

| 19. Is consuming alcohol 3 times a day more harmful for patients with CHD than for other people? | 20 | (13.5%) | 96 | (64.9%) | 23 | (15.5%) | 9 | (6.1%) | 0 | 0 |

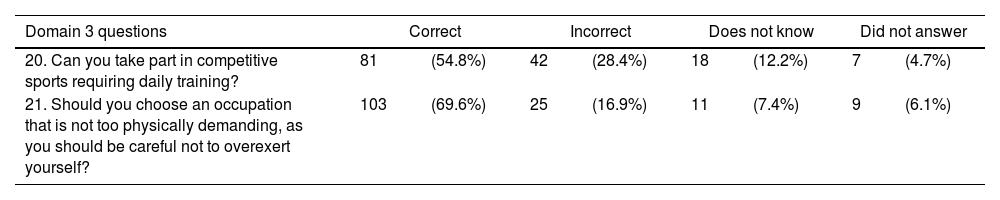

In our population, 81 (54.8%) patients were aware of the recommendations for physical activity regarding their diagnosis, not being allowed to take part into competitive sports requiring daily training and 103 (69.6%) patients knew they should choose an occupation not too physically demanding (Table 5).

Frequency of patients’ knowledge about physical activity (n=148).

| Domain 3 questions | Correct | Incorrect | Does not know | Did not answer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20. Can you take part in competitive sports requiring daily training? | 81 | (54.8%) | 42 | (28.4%) | 18 | (12.2%) | 7 | (4.7%) |

| 21. Should you choose an occupation that is not too physically demanding, as you should be careful not to overexert yourself? | 103 | (69.6%) | 25 | (16.9%) | 11 | (7.4%) | 9 | (6.1%) |

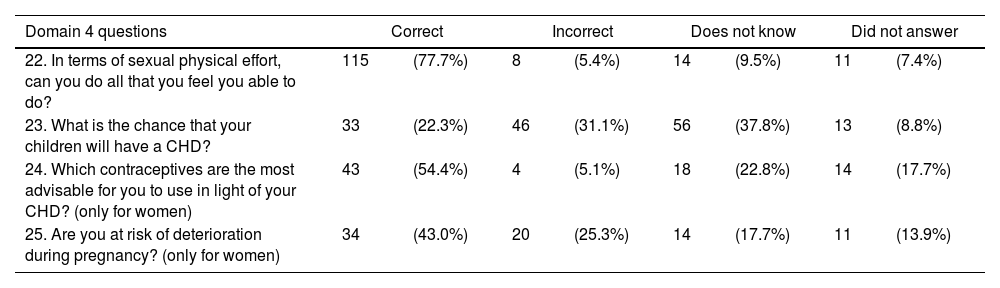

Regarding the reproductive issues domain (Table 6), most patients (77.7%) knew they were allowed to engage in sexual intercourse if capable of doing so. A small proportion of patients (22.3%) had adequate knowledge about the hereditary nature of their CHD. Approximately half of the women used intra uterine devices and oral contraceptive as adequate contraceptive choices. Fifty seven percent women did not know they may be at risk of clinical deterioration during pregnancy.

Frequency of patients’ knowledge about reproductive issues (n=148).

| Domain 4 questions | Correct | Incorrect | Does not know | Did not answer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. In terms of sexual physical effort, can you do all that you feel you able to do? | 115 | (77.7%) | 8 | (5.4%) | 14 | (9.5%) | 11 | (7.4%) |

| 23. What is the chance that your children will have a CHD? | 33 | (22.3%) | 46 | (31.1%) | 56 | (37.8%) | 13 | (8.8%) |

| 24. Which contraceptives are the most advisable for you to use in light of your CHD? (only for women) | 43 | (54.4%) | 4 | (5.1%) | 18 | (22.8%) | 14 | (17.7%) |

| 25. Are you at risk of deterioration during pregnancy? (only for women) | 34 | (43.0%) | 20 | (25.3%) | 14 | (17.7%) | 11 | (13.9%) |

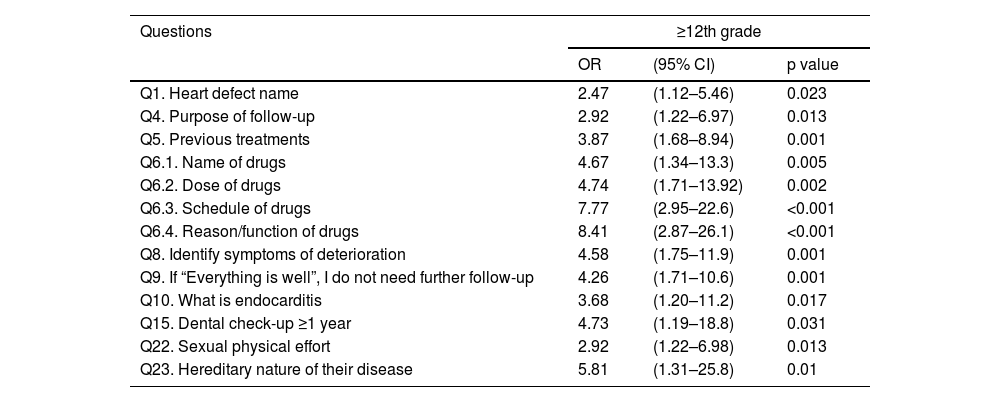

The main findings of the secondary analysis of association between the level of education (≥12th grade) and disease complexity (non-severe) with correct knowledge of LKQ for CHD is depicted in Table 7 (see Supplementary Table S1 for complete data). Compared to less educated patients, the ones with higher education have greater odds of knowing the name of their CHD (p=0.023), to have more adequate knowledge about previous treatments (p=0.001) and to identify symptoms and signs of clinical deterioration correctly (p=0.001). Having at least the 12th grade of education was associated with greater odds of acknowledging what endocarditis is and having a dental check-up at least once a year (p=0.017 and p=0.031, respectively), compared to their counterparts. Regarding reproductive issues, patients with higher education have higher knowledge regarding sexual activity (p=0.013) and the hereditary nature of their CHD (p=0.01).

Main findings on the association between level of education and complexity of the disease with CHD knowledge.

| Questions | ≥12th grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Q1. Heart defect name | 2.47 | (1.12–5.46) | 0.023 |

| Q4. Purpose of follow-up | 2.92 | (1.22–6.97) | 0.013 |

| Q5. Previous treatments | 3.87 | (1.68–8.94) | 0.001 |

| Q6.1. Name of drugs | 4.67 | (1.34–13.3) | 0.005 |

| Q6.2. Dose of drugs | 4.74 | (1.71–13.92) | 0.002 |

| Q6.3. Schedule of drugs | 7.77 | (2.95–22.6) | <0.001 |

| Q6.4. Reason/function of drugs | 8.41 | (2.87–26.1) | <0.001 |

| Q8. Identify symptoms of deterioration | 4.58 | (1.75–11.9) | 0.001 |

| Q9. If “Everything is well”, I do not need further follow-up | 4.26 | (1.71–10.6) | 0.001 |

| Q10. What is endocarditis | 3.68 | (1.20–11.2) | 0.017 |

| Q15. Dental check-up ≥1 year | 4.73 | (1.19–18.8) | 0.031 |

| Q22. Sexual physical effort | 2.92 | (1.22–6.98) | 0.013 |

| Q23. Hereditary nature of their disease | 5.81 | (1.31–25.8) | 0.01 |

| Non-severe CHD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Q2. Describe/indicate on the diagram | 6.65 | (1.47–30.1) | 0.006 |

| Q3. Follow-up | 6.3 | (1.29–30.9) | 0.039 |

| Q6.1. Name of drugs | 4.63 | (1.52–12.32) | 0.02 |

| Q15. Dental check-up ≥1 year | 7.14 | (1.72–29.7) | 0.013 |

Patients with non-severe CHD were more often able to correctly to describe or indicate on the diagram where their heart defect is, and to have more adequate knowledge about their follow-up and to correctly identify the names of their medication (p=0.006; p=0.039; p=0.02, respectively).

DiscussionPatients with CHD have a complex condition and face daily challenges that require proper healthcare structures to provide high quality treatment.1

To guarantee appropriate education is a critical element in patient management in order to improve their knowledge and awareness of the need to adopt good health behaviors regarding their CHD.14–17

In this study we assessed the level of knowledge in a sample of ACHD followed-up in a specialized ACHD tertiary care center. Overall, our findings demonstrated that patients had good knowledge (more than 80% giving correct answers) about the frequency of follow-up, the need to continue follow-up even if the condition is stable, the need for dental check-up once a year and to clean their teeth at least once a day. They were less knowledgeable (50–80% giving correct answers) about the name of their heart defect, the purpose of clinical follow-up, previous treatments, pharmacotherapy, to call first their assistant cardiologist if they have fever, to take antibiotics before dental procedures, about the appropriateness of physical activities and vocational choices, to engage in sexual intercourse and to recognize adequate contraceptives. Knowledge was considered poor (less than 50% giving correct answers) localizing their heart defect, to recognize drug side effects and interactions, how to act in case of experiencing drug side effects, to recognize at least two symptoms of clinical deterioration, to adequately define endocarditis and recognize its potential recurrence and most typical sign and risk factors, the impact of smoking and alcohol consumption, to acknowledge the hereditary nature of their CHD and risk of clinical deterioration during pregnancies.

Furthermore, the median age of our sample was 39 years, older than previous observational studies10,12 which highlights the importance of dedicated programs to improve health-related education in this patient setting, given their longer lifespan.

In fact, Mackie et al.18 demonstrated a reduced chance of a delay in obtaining adult CHD care with a nurse-led transition intervention directed at older adolescents at 16 or 17 years of age. Still, in the same study, differences in knowledge using the MyHeart score were not observed between the intervention and control group. Although very different aims and methodology were used between our study and the latter, important messages can be inferred when looking at the results together. First, both studies highlight the continuum of care at different stages of the disease that CHD requires. On the one hand, structured programs for adolescent to adulthood transitioning ensures there is no delay in obtaining adult care. On the other hand, at approximately 20 years of age, apart from the two study populations, a significant knowledge gap is still observed after this longer lifespan. This provides valuable information for clinicians to improve patients’ information and skills continually regarding their CHD during their medical visits across time.

Regarding other similar studies, most of our patients had an education level ≥12th grade and were employed, which indicates a good cognitive background and significant level of capacity and independence.19 In fact, some findings from our study are to a certain extent similar to those in previous studies. In the observational study by Moons et al., 50–61% were able to describe/indicate or provide the name of the heart defect. In the present study, 40–58% had adequate knowledge about their CHD name. In contrast, in our sample, 42.9% of patients were able to identify at least two symptoms of clinical deterioration as opposed to 30.6% in Moon et al study.

A significant lack of knowledge regarding the definition of endocarditis, the most typical symptom and risk factors for the disease was observed. This result was consistent with previous research, both adult and adolescent to adult transitioning focused studies.10,12,20,21 Nevertheless, there was good knowledge about dental practices and the need for antibiotics for dental procedures, as reported in other studies.

Compared to previous research, our patients had less knowledge regarding physical activities and the risk of clinical deterioration during pregnancy. The knowledge about the hereditary nature of CHD was consistently poor.12

Patients with an education level equal to or superior to 12th grade had greater knowledge of various items. Of note, less educated patients had significantly less knowledge of the name of their disease, follow-up and previous treatments, symptoms of clinical deterioration and endocarditis. These findings emphasize the need for an individualized approach to patient care, particularly for those with lower education levels, to ensure comprehensive education, support, and engagement in their health.

In addition, our findings demonstrate that, overall, the complexity of CHD is not associated with better performance in answers. An exception to this observation is the ability to locate the heart defect, the insights about clinical follow-up, the name of their pharmacotherapy and dental checkup, as non-severe CHD patients outperformed the ones with severe CHD.

This finding is particularly interesting, since patients with more complex disease, who might have more reasons for concern and more stimuli for a better insight, actually had less knowledge of the disease in some areas. Few studies have demonstrated that adults with complex CHD tend to have worse performances in neurocognitive assessments comparing to both non-severe adults with CHD or age-matched population norm,22,23 which had also previously been reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD.24 These patients may have an inherent risk involved with having a severe form of CHD, since there may be a direct relationship between brain diseases and CHD.25 Furthermore, these patients often undergo high-risk surgeries with cardiopulmonary bypass, preoperative and postoperative cerebral perfusion and seizures, which may have a long-term impact on neurocognition.26 These issues related to more complex CHD may help to understand some of the findings of our study.

By addressing these knowledge gaps and providing tailored information, healthcare professionals can empower patients to actively participate in their own care and make informed decisions regarding their health.

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. First, the Leuven Questionnaire for CHD has been validated for Brazilian Portuguese but not for the Portuguese population. We acknowledge that the process of adapting instruments such as questionnaires should consider the concepts and domains originally studied and adapt each item to a different culture. Still, we had the opportunity to compare and qualitatively assess the two versions before giving them to patients. After careful analysis, we agreed that the content and interpretation of the questions was not compromised or significantly different from the English and Brazilian version. Despite this limitation, we considered the main goal of our study would be adequately addressed with our version, as these versions correlate highly.

In addition, selection bias might be present, and the population may not be representative of the entire population of adults with CHD, as the study was conducted at a specific healthcare institution and the opportunistic recruitment of patients may contribute to a less heterogenous sample. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to recall bias or social desirability bias. The cross-sectional design of the study limits our ability to establish causality or examine changes in knowledge over time. The authors considered “does not answer” as an answer itself to reduce the missing data, which might have had a positive or negative impact on the overall results. Finally, the study focused solely on specific aspects of knowledge and did not explore other relevant factors such as psychological well-being or quality of life.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study sheds light on the knowledge gaps among adults with CHD. The findings reveal significant deficiencies in understanding various domains: disease and treatment, endocarditis and preventive measures, physical activities, and reproductive issues. It is crucial for individuals with CHD to possess adequate knowledge and understanding of their condition to actively engage in their healthcare decisions and participate in self-management, along with their families. The study underscores the need for tailored information, guidance, and structured educational programs to bridge these knowledge gaps and empower patients to take an active role in their care. By addressing these challenges, healthcare providers can enhance patient outcomes, improve quality of life, and promote long-term well-being for individuals with CHD.

As future perspectives and taking into consideration these results and other studies in the area, we are developing a structured nurse and physician-directed educational program using the LKQ for CHD to prospectively assess the change in knowledge in adults with CHD overtime. Furthermore, we designed a transition program from adolescent to adulthood with the intention of prospectively analyzing its impact on CHD knowledge.

Finally, from a national perspective, our center represents one of the highest volume tertiary centers in Portugal with both adults with CHD and pediatric cardiology specialized teams. We believe our results may be representative of other Portuguese centers. This work paves the way for addressing this issue in a national-based strategy for further development of care for adults with CHD in Portugal.

Ethical approvalEthics Committee of Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central Observational study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.