Patients with angina and a positive single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan for reversible ischemia, with no or non-obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) on invasive coronary angiography (ICA), represent a frequent clinical problem and predicting prognosis is challenging.

MethodsThis was a retrospective single-center study on patients who underwent elective ICA with angina and a positive SPECT with no or non-obstructive CAD over a seven-year period. Cardiovascular morbidity, mortality, and major adverse cardiac events were assessed during a follow-up of at least three years after ICA, with the aid of a telephone questionnaire.

ResultsData on all patients who underwent ICA in our hospital over a period of seven years (between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2017) were analyzed. A total of 569 patients fulfilled the pre-specified criteria. In the telephone survey, 285 (50.1%) were successfully contacted and agreed to participate. Mean age was 67.6 (SD 8.8) years (35.4% female) and mean follow-up was 5.53 years (SD 1.85). Mortality was 1.7% (four patients, from non-cardiac causes), 1.7% underwent revascularization, 31 (10.9%) were hospitalized for cardiac reasons and 10.9% reported symptoms of heart failure (no patients with NYHA class>II). Twenty-one had arrhythmic events and only two had mild anginal symptoms. It was also noteworthy that mortality in the uncontacted group (12 out of 284, 4.2%), derived from public social security records, did not differ significantly from the contacted group.

ConclusionsPatients with angina, a positive SPECT for reversible ischemia and no or non-obstructive CAD on ICA have excellent long-term cardiovascular prognosis for at least five years.

Os doentes com angina e com cintigrafia de perfusão miocárdica positiva (isquemia reversível) sem DC ou com DC não obstrutiva na coronariografia (CI) representam um problema clínico frequente e o seu prognóstico constitui um desafio.

MétodosEste estudo unicêntrico retrospetivo focou-se em doentes com angina e com cintigrafia de perfusão miocárdica positiva submetidos a coronariografia eletiva que revelou ausência de DC ou DC não obstrutiva durante um período de sete anos. Foi efetuada a avaliação da morbilidade, mortalidade cardiovasculares e de eventos cardíacos adversos major durante um período de seguimento de pelo menos três anos após a coronariografia, por questionário por telefone.

ResultadosForam analisados os dados de todos os doentes submetidos a coronariografia durante um período de sete anos (de 1 de janeiro de 2011 a 31 de dezembro de 2017) no nosso hospital. Os doentes que preencheram os critérios pré-definidos foram 569. No inquérito realizado por telefone, 285 (50,1%) foram contactados com sucesso e acederam em participar. A idade média foi de 67,6 anos (SD8,8) (mulheres - 35,4%) e o período de seguimento médio foi 5,53 anos (SD1,85). A taxa de mortalidade foi de 1,7% (quatro doentes por causas não cardíacas) e de 1,7% de taxa de revascularização. Foram hospitalizados 31 (10,9%) doentes por causas cardíacas e 10,9% apresentaram sintomas de IC (nenhum doente com Classe>II NYHA); 21 tiveram eventos arrítmicos e apenas dois tiveram ligeiros sintomas de angina. É de salientar que a taxa de mortalidade no grupo não contactado (12 de 284, 4,2%) proveniente dos registos de saúde pública não diferiu significativamente da do grupo contactado.

ConclusõesOs doentes com angina, com cintigrafia de perfusão miocárdica positiva (isquemia reversível) e com DC não obstrutiva ou sem DC tiveram um excelente prognóstico cardiovascular a longo prazo, durante pelo menos cinco anos.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) imaging has become established as the main functional cardiac imaging technique for ruling in or out myocardial ischemia for patients with angina.1 Thallium stress scintigraphy, following an exercise test or using pharmacologic stressors, was the mainstay for myocardial ischemia diagnosis for decades. Lately technetium and single-photon emission tomography (SPECT) techniques have replaced thallium and traditional scintigraphy, respectively, in the vast majority of studies, providing high diagnostic accuracy with low radiation. Defects in stress and rest images of a myocardial SPECT scan are considered indicative of impaired myocardial perfusion, usually due to stenosis or even total occlusion of coronary arteries.2

The degree of epicardial coronary artery stenosis cannot be determined unless angiography is conducted. On angiography, normal-appearing coronary arteries are defined as having 0% or <20% luminal stenosis, and non-obstructive CAD as coronary arteries with luminal stenosis >20% but <50%. Although the traditional definition of obstructive CAD was ≥70% stenosis, recent European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines shifted to include stenosis of 50–70% if there is associated inducible ischemia or fractional flow reserve ≤0.80 when considering the physiological significance of stenosis and revascularization management in patients with stable CAD.3

Several studies have shown a particularly high percentage of false positive SPECT scans for significant epicardial CAD, ranging from 25% up to more than 50% depending on the study, for patients with no or non-obstructive coronary artery disease.4–6 Perfusion defects on SPECT scans of these patients may sometimes be artifacts caused by technical issues (attenuation of signal due to radiation absorption from adjacent tissues, such as the diaphragm, being the most common cause).7 However, there is also concern about other conditions in these patients (such as myocardial bridging, vasospastic angina, or impaired microvascular flow as in diabetes and hypertensive cardiomyopathy).

The clinical condition recently identified as ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA)3,8–10 is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and poor prognosis in subsequent years. Long-term follow-up of patients after SPECT studies indicative of reversible ischemia but without proven significant CAD on coronary angiography could provide answers to these questions.

MethodsStudy populationWe conducted a retrospective single-center study reviewing the database of the catheterization laboratory of a tertiary general hospital that carries out approximately 1600–1700 catheterizations per year. Our initial search focused on patients who underwent invasive coronary angiography with an indication of angina and a positive myocardial SPECT scan for reversible ischemia in at least three myocardial segments, corresponding to an ischemic area of at least moderate size, during a pre-specified period of three months. The study's timeframe was seven years, finishing three years before the retrospective study was conducted, with the intention to extend the minimum follow-up period for every patient included in our study to more than three years. We excluded all patients with an implanted device (pacemaker or defibrillator), history of cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, or myocardial revascularization with significant epicardial coronary artery disease. We also excluded patients in whom angiography revealed significant CAD, but severe comorbidities made unsuitable for intervention and were recommended to be restricted to medical treatment. Finally, due to concerns of a high probability of SPECT studies indicative of reversible ischemia but without proven significant CAD on coronary angiography,11,12 all patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB) morphology on the resting electrocardiogram (ECG) were also excluded from the study.

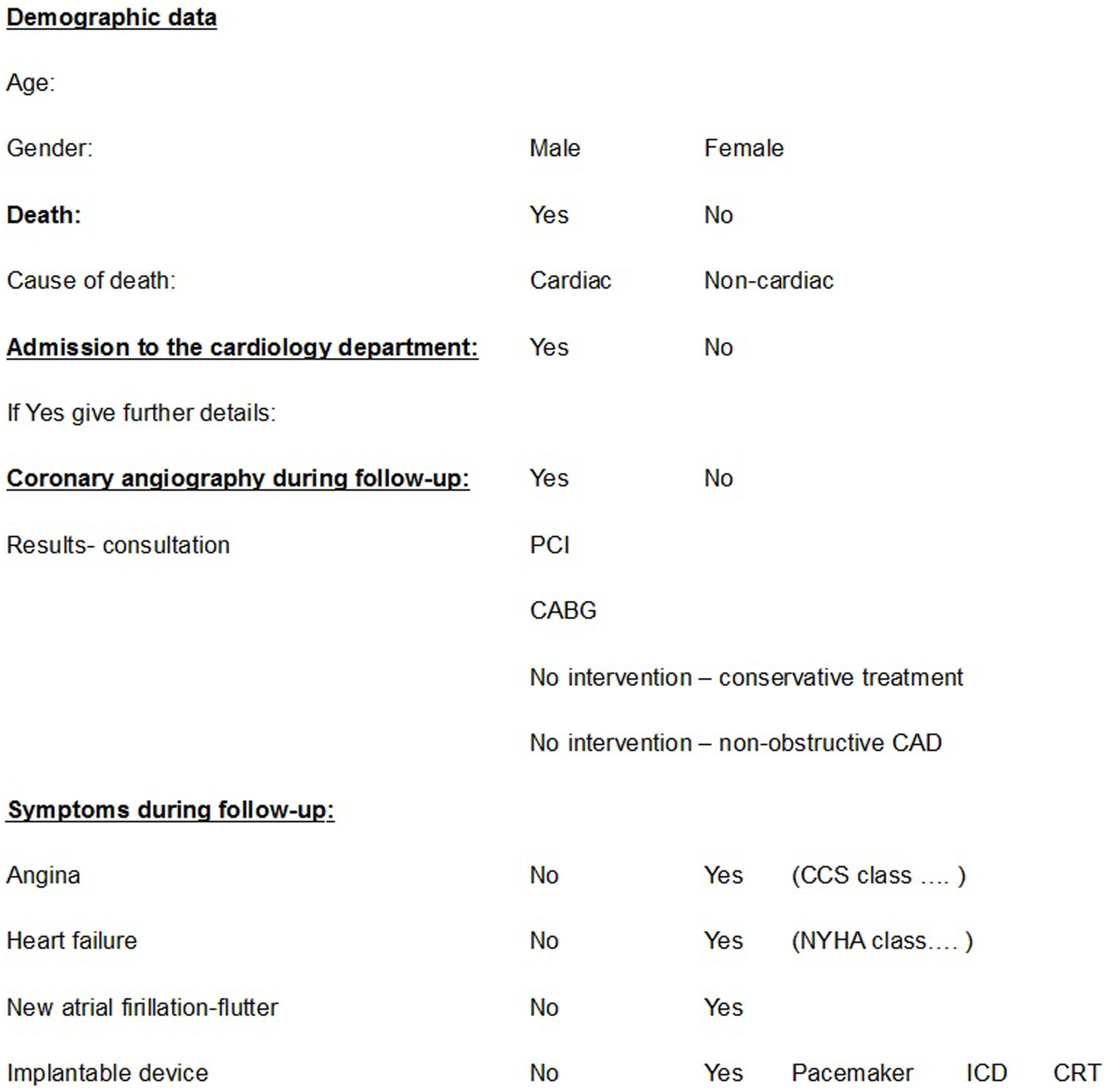

The remaining patients, with no or non-obstructive epicardial CAD, symptoms of angina and a positive myocardial SPECT, were studied further. Telephone contact was attempted with the patients or their family and those who agreed to participate in the study answered a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, mainly focusing on death from any cause, cardiovascular death, hospitalization for any reason related to cardiovascular disease, myocardial revascularization, angina, arrhythmias, and heart failure. The questionnaire is presented in Table 1.

Study questionnaire (administered during follow-up after coronary angiography).

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy device; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

For patients who could not be contacted by telephone, we searched in public records using their social security numbers and tracing those who were deceased in order to create a ‘control group’ for mortality, since we were concerned about the possibility of significantly higher mortality in patients who could not be contacted. No other data on patients who were deceased or who could not be contacted were analyzed, since it was impossible to obtain consent for their inclusion in the study. The protocols of the study, as well as the questionnaire used for the telephone interviews, were approved by the hospital's ethics committee.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphyAll the MPIs were performed with the most commonly used medical radioisotope, the metastable nuclear isomer of technetium-99 (99mTc), without implementation of a gated technique in the majority of scans. Due to the retrospective nature of our study and lack of sufficient data on ischemia distribution, the SPECT results were classified solely as positive or negative for ischemia.

Coronary angiographyAll coronary angiographies were performed within three months of the SPECT scans at Konstantopouleio General Hospital (Nea Ionia, Athens, Greece), using a Philips Allura Xper FD20 X-ray system. Left heart catheterization was performed using a standard Judkins technique, and images were obtained in multiple views. Angiographic results were analyzed anatomically by two experienced interventional cardiologists and significant stenosis was defined as narrowing of the vessel lumen by more than 50%. If there was disagreement regarding the percentage of stenosis of the lesions, invasive coronary angiography-based quantitative coronary analysis (QCA) was performed on each controversial stenotic lesion at the borderline of ∼50%. QCA software on the workstation was then used to detect luminal edges, locate the site of maximum stenosis, and quantify its degree. Whenever automatic edge detection failed, manual edge tracing was performed.

Statistical analysisVariables with approximately symmetric distributions were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD). For comparisons of proportions, chi-square tests were used. All p-values reported are two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and analyses were conducted using SOFA Statistics software (version 1.5.3).

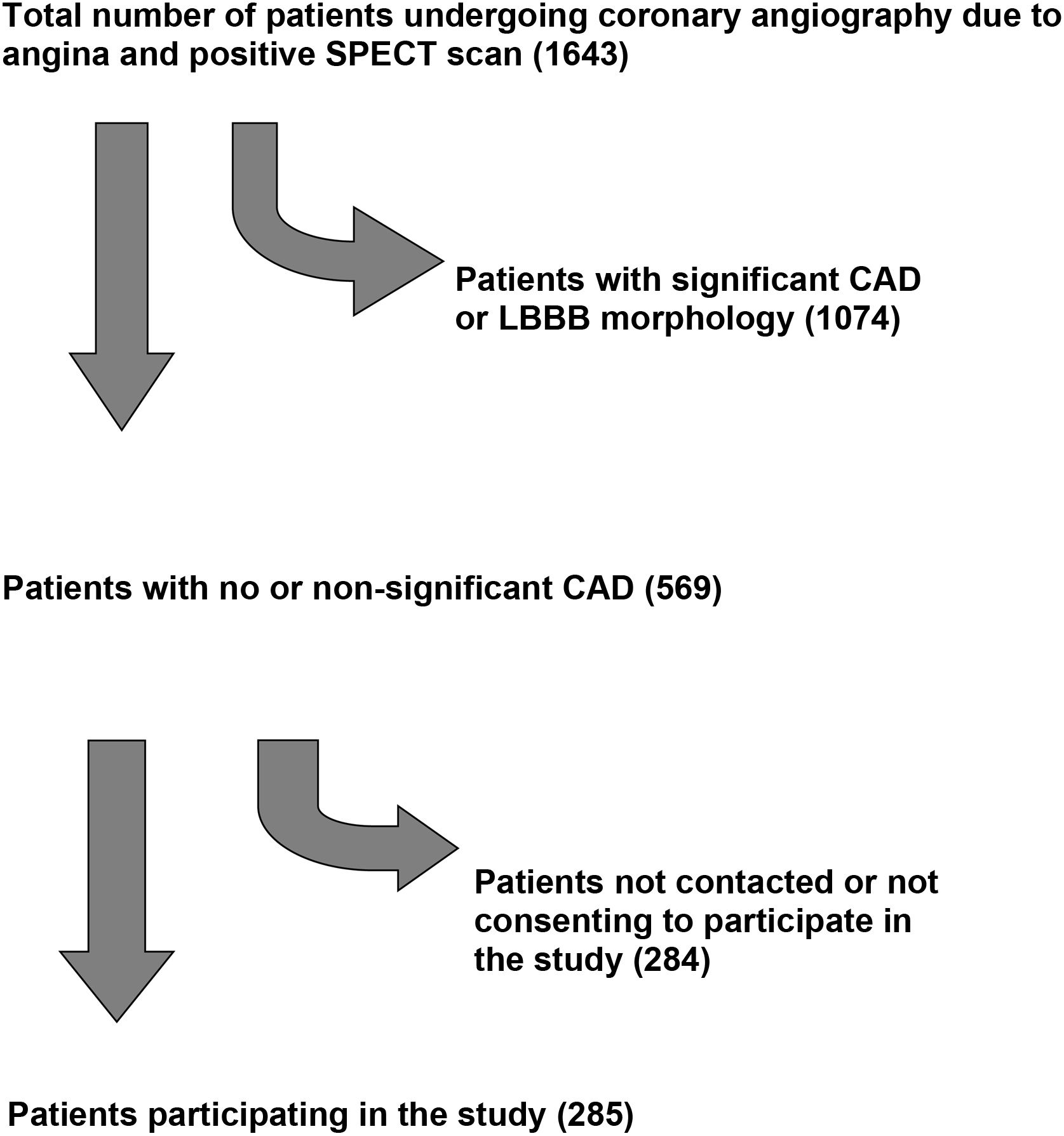

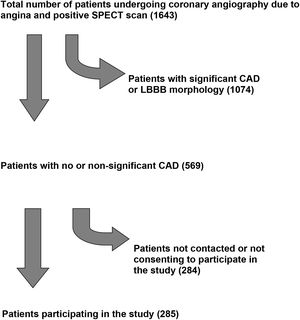

ResultsDuring January 2021 we retrospectively analyzed data on all patients who underwent coronary angiography in the catheterization laboratory of the Konstantopouleio General Hospital of Nea Ionia over a period of seven years (between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2017). A total of 1643 patients (from a total of 12536 angiographies) fulfilled criteria of angina and a positive myocardial SPECT scan for reversible ischemia. No or non-significant coronary artery disease was the diagnosis after coronary angiography in 569 patients (34.63%). In the telephone survey that followed, 285 (50.1%) of these were successfully contacted, either in person or via a close relative who answered the call and agreed to participate in the study. The study flowchart is depicted in Figure 1.

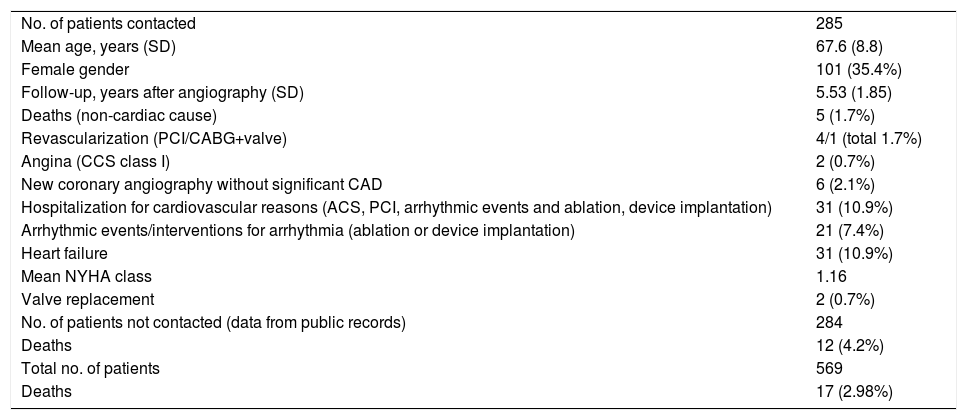

The mean age of patients included in the analysis was 67.6 (SD 8.8) years, 35.4% were female, and mean follow-up was 5.53 years (SD 1.85). At the time of telephone contact five had died (1.7%), none of them of cardiac causes. Five (1.7%) underwent revascularization (four percutaneous and one coronary artery bypass graft during valve replacement surgery) in the subsequent years, in a mean period of approximately six years after the index coronary angiogram, and six patients (2.1%) had another coronary angiogram, still without significant epicardial coronary artery disease or need for revascularization. A much higher number of patients had arrhythmic events in subsequent years, with a composite of new-onset atrial fibrillation or flutter, ablation for arrhythmias of any origin or pacemaker implantation in 21 patients (7.4%). Two patients (0.7%) reported symptoms of angina (both Canadian Cardiovascular Society class I) and two patients (0.7%) had valve replacement surgery. A total of 31 patients were hospitalized for cardiovascular reasons during follow-up (10.9%), none of them with symptoms of heart failure. Another 31 patients (10.9%) reported symptoms of heart failure during follow-up, but with a mean New York Heart Association (NYHA) class of only 1.16 and no patients in NYHA class>II. No patients reported definite symptoms of angina.

Another important finding is that mortality in the group of patients that could not be contacted (12 patients out of 284, 4.2%) did not differ significantly from that of the contacted patients (X2 [1,n=569]=2.07, p=0.15). These results are depicted in Table 2. Moreover, since INOCA are more frequent in women than (50-70%) we analyzed separately the group of women (results in Table 3). In our study, the subgroup of female patients numbered 101 individuals with a mean age of 69.2 (SD 8.4) years and a mean follow-up time of 5.51 (SD 1.69) years. Mortality was less than 1% (one death from non-cardiac cause, 0.99%) and cardiovascular events during follow-up included one percutaneous revascularization, eight arrhythmic events/interventions and eight hospitalizations. These results are depicted in Table 3. Finally, another noteworthy result is that all the observed myocardial bridges (nine, 3.2%) were in male patients in the course of the left anterior descending artery and were not associated with adverse long-term outcomes (except for mild dyspnea on exertion in two).

Study results.

| No. of patients contacted | 285 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 67.6 (8.8) |

| Female gender | 101 (35.4%) |

| Follow-up, years after angiography (SD) | 5.53 (1.85) |

| Deaths (non-cardiac cause) | 5 (1.7%) |

| Revascularization (PCI/CABG+valve) | 4/1 (total 1.7%) |

| Angina (CCS class I) | 2 (0.7%) |

| New coronary angiography without significant CAD | 6 (2.1%) |

| Hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons (ACS, PCI, arrhythmic events and ablation, device implantation) | 31 (10.9%) |

| Arrhythmic events/interventions for arrhythmia (ablation or device implantation) | 21 (7.4%) |

| Heart failure | 31 (10.9%) |

| Mean NYHA class | 1.16 |

| Valve replacement | 2 (0.7%) |

| No. of patients not contacted (data from public records) | 284 |

| Deaths | 12 (4.2%) |

| Total no. of patients | 569 |

| Deaths | 17 (2.98%) |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation.

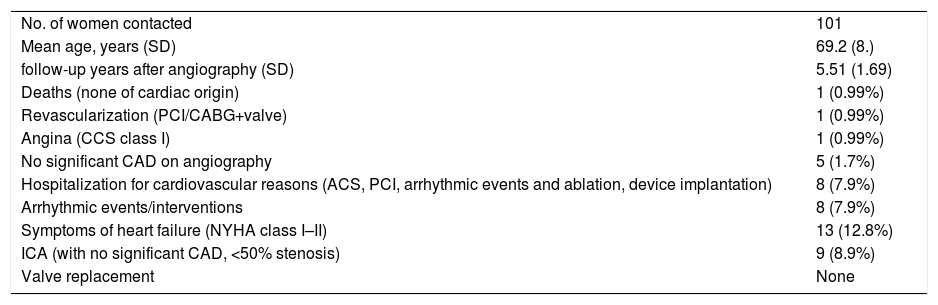

Study results: women subgroup.

| No. of women contacted | 101 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 69.2 (8.) |

| follow-up years after angiography (SD) | 5.51 (1.69) |

| Deaths (none of cardiac origin) | 1 (0.99%) |

| Revascularization (PCI/CABG+valve) | 1 (0.99%) |

| Angina (CCS class I) | 1 (0.99%) |

| No significant CAD on angiography | 5 (1.7%) |

| Hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons (ACS, PCI, arrhythmic events and ablation, device implantation) | 8 (7.9%) |

| Arrhythmic events/interventions | 8 (7.9%) |

| Symptoms of heart failure (NYHA class I–II) | 13 (12.8%) |

| ICA (with no significant CAD, <50% stenosis) | 9 (8.9%) |

| Valve replacement | None |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation.

In this small retrospective single-center study, we showed that patients with angina and a positive SPECT scan indicating reversible ischemia but no significant epicardial coronary artery disease on coronary angiography have excellent long-term prognosis in subsequent years and very low cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The particularly long mean follow-up of the study (more than 5.5 years), the evidence of no cardiac deaths, and a very low rate of revascularization during follow-up enhance the value of our results. The fact that mortality in patients lost to follow-up was not significantly different could be considered an indication of similarity between the two groups, at least for major outcomes. The rate of hospitalization for cardiovascular causes during the follow-up period was fairly low, and the majority were related to arrhythmic events and conduction disturbances rather than acute coronary syndromes. Symptoms of heart failure were reported by one in 10 patients, but most of them were in NYHA class I and there were no related hospitalizations. The particularly low number of patients complaining of angina is quite striking, although the questionnaire used is not validated and we cannot exclude the possibility of misinterpretation of symptoms of angina or heart failure.

Our study certainly lacks sufficient data to identify how many of our patients had real dynamic macro- or microvascular impairment, which could explain the positive SPECT scan results, and how many cases were simply artifacts of the SPECT study. However, the very low overall rate of poor outcomes in the majority of patients during a long follow-up period probably renders such a question unnecessary.

Our study had a lower rate of SPECT studies indicative of reversible ischemia but without proven significant CAD on coronary angiography (569 patients out of 1643, 34.63%) than other contemporary studies. Similar rates are reported in early studies of MPS performed in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, with a significant number of gated SPECT scans and supine and prone acquisitions.13 However, later real-world series report significantly higher rates (over 50%) of false positive scans, raising questions concerning the accuracy of the method for ruling in patients for coronary angiography and the resulting cost of such a strategy. An explanation for the low number of false positive scans in our study could be that we excluded from the analysis all patients with LBBB morphology on the resting ECG before coronary angiography. Furthermore, recent literature suggests that this morphology could be a source of a higher rate of false positive SPECT scans and subsequently misdiagnosis, leading to unnecessary coronary angiograms.11

Our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study, and the lack of comprehensive clinical information on the patients’ medical history when they underwent the SPECT scan and the index coronary angiography, deprives us from data regarding the etiology of positive SPECT studies without significant CAD. Second, the considerable number of patients who could not be contacted is an issue that could raise suspicion of higher mortality and/or morbidity and cardiovascular event rate in this group. Nevertheless, the fact that the data, which were obtained from public social security records, did not show statistically significant differences in terms of mortality (irrespective of etiology) is partially reassuring. Another limitation is that follow-up was via telephone contact with a non-validated questionnaire and the accuracy of the answers could be questioned, particularly when quantitative data like NYHA functional class were assessed. We also had no data in our sample regarding the percentage of exercise stress versus vasodilator stress SPECT scans, parameters that are known to affect the sensitivity and specificity of CAD diagnosis in MPS, together with the low percentage of gated SPECT scans. Finally, the limited SPECT scan data regarding the amount and distribution of area at risk in non-revascularized patients, albeit with a diagnosis of positive SPECT, may have contributed to the very low cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the years following the index coronary angiography.

Finally, we observed very low morbidity and mortality in women participants during more than five years of follow-up. This result is not in accord with other INOCA studies. For example, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study revealed that the prognosis of women with INOCA is far from benign.14 The small number of women in our study, as well as our inability to determine the reason for positive SPECT studies without significant CAD (artifacts, INOCA or others), may be responsible for this discrepancy with previous data.

ConclusionsMPS is an important step between clinical assessment and coronary angiography for patients with symptoms of angina. In this small retrospective study, we showed that the long-term prognosis for INOCA patients with a positive SPECT scan for reversible myocardial ischemia is excellent as far as cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are concerned. We also demonstrated that excluding patients with LBBB morphology on the resting ECG can improve the diagnostic accuracy of myocardial SPECT scans regarding detection of significant CAD.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We gratefully acknowledge the help of the staff of the Catheterization Laboratory of Konstantopouleio General Hospital Nea Ionia, Athens, Greece.