Patient knowledge about hypertension is an important patient-related determinant for poor blood pressure control and is a target for more effective interventions. We aimed to evaluate hypertensive patients’ knowledge and awareness about hypertension and its influence on their beliefs about their medication and their adherence to antihypertensive therapy.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted among adult patients attending one of the participating pharmacies and taking at least one antihypertensive drug. Data on personal and family history were collected, and Portuguese versions of the Hypertension Knowledge Test (HKT), Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ), and short version of the Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension questionnaire (MUAH-16) were administered.

ResultsA total of 240 patients were enrolled. The mean number of antihypertensive drugs used was 1.62±0.99, with 15.4% of patients treated with three or more drugs. More than 80% of patients knew the blood pressure therapeutic goals and identified overweight, sedentary lifestyle, and salt as risk factors for hypertension. Conversely, the majority of the patients were not aware of the asymptomatic characteristics of hypertension and believed that antihypertensive treatment had to be used for a limited time duration. Negative and significant correlations were found between the HKT and negative attitudes toward medication, but no association was found with positive attitudes.

ConclusionsHypertensive patients had good knowledge of hypertension risk factors but not of antihypertensive treatment. Increasing patient knowledge about hypertension may possibly reduce negative attitudes toward medication but will probably have no impact on positive attitudes.

O conhecimento dos doentes sobre hipertensão é um importante fator associado ao mau controlo da pressão arterial e é uma das variáveis consideradas para desenhar intervenções mais efetivas. O nosso objetivo foi avaliar o conhecimento dos doentes hipertensos sobre hipertensão e determinar a sua influência nas crenças sobre medicação e na adesão à terapêutica destes doentes.

MétodosEstudo transversal. Doentes adultos que se dirigiram a uma das farmácias participantes e a tomar pelo menos um medicamento anti-hipertensor foram convidados. Foram recolhidos dados sobre a história familiar e pessoal e administradas as versões portuguesas dos questionários Hypertension Knowledge Test (HKT), Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) e versão curta do Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension questionnaire (MUAH-16).

ResultadosForam incluídos 240 doentes no estudo. O número médio de anti-hipertensores utilizados foi 1,62±0,99, usando 15,4% dos doentes três ou mais fármacos. Mais de 80% dos doentes sabia os valores de pressão arterial ideais e reconheceram obesidade, sedentarismo e sal como fatores de risco para a hipertensão. No entanto, a maioria dos doentes não estava ciente das características assintomáticas da hipertensão e acreditava que os anti-hipertensores deviam ser utilizados por tempo limitado. Correlações negativas e significativas foram encontradas entre o score obtido no HKT e as atitudes negativas em relação à medicação, mas não foi encontrada nenhuma associação com as atitudes positivas.

ConclusõesOs doentes hipertensos têm um bom conhecimento sobre os fatores de risco da hipertensão, mas não sobre o seu tratamento. Aumentar os conhecimentos dos doentes sobre hipertensão pode reduzir as atitudes negativas associadas à medicação, mas provavelmente não terá nenhum impacto nas atitudes positivas.

Prevention and control of lifestyle-related modifiable risk factors, such as smoking, diet, salt intake, and exercise, are well-known strategies to improve blood pressure control and consequently reduce the incidence of vascular and metabolic diseases and other disabling conditions.1 However, in different populations other factors have been associated with hypertension control, such as patient knowledge about hypertension, patient beliefs about medicines, and patient adherence to antihypertensive therapy.2,3 As such, when designing interventions to improve hypertensive patients’ blood pressure control, these other factors should be addressed, and tailored interventions should be designed. Increasing patient knowledge regarding cardiovascular diseases, their treatment and risk factors has become an important goal in public health interventions, with several studies showing that patients who had been educated about the importance of treatment were more involved with their therapy, more likely to adopt healthy lifestyle changes and more likely to see their physician if their blood pressure was outside the ideal range.4,5

In Portugal, some studies have assessed the knowledge of hypertensive patients regarding their disease as well as the relationship between patients’ knowledge and blood pressure control6,7; however, none of these studies used a validated instrument, hindering cross-sectional and longitudinal replicability. In 2017, Cabral et al. developed the Portuguese version of the Hypertension Knowledge Test (HKT),8 a multifaceted instrument that assesses knowledge about hypertension, not only regarding the symptoms and diagnosis of the disease but also regarding the ways of preventing and controlling high blood pressure, antihypertensive medications, and the harmful effects of hypertension over time. With this instrument, a potential standard exists that allows not only the assessment of patients’ knowledge about hypertension but also the evaluation of whether patient knowledge is associated with process variables, such as patients’ beliefs about medicines and treatment adherence.

Identifying the association between these parameters and their extent will enable clinicians, researchers, and health policy decision makers to develop more targeted and effective educational activities.

ObjectivesWe aimed to evaluate hypertensive patients’ knowledge about hypertension and its influence on patients’ beliefs about their medication and on patients’ antihypertensive treatment adherence.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Coimbra (registration number: CE_024.2018). The study aims and procedures were explained to all potentially eligible patients. The acceptance of study participation was indicated by each patient upon signing of the written informed consent form.

Hypertension Knowledge TestThe Hypertension Knowledge Tests (HKT) is an easy-to-use questionnaire created to assess patients’ knowledge about hypertension; it covers several aspects of the disease (etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention). Originally created in 2011,9 this instrument was cross-culturally validated to European Portuguese in 2017.8 The HKT comprises two parts: 12 true-or-false questions and 9 multiple-choice questions. The level of knowledge is calculated by assigning one point to each correct answer, obtaining a total score ranging from 0 to 21.

Beliefs about Medicines QuestionnaireThe Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) is an eleven-item questionnaire that comprises two subscales: a five-item “necessity” scale to assess beliefs about the need for the prescribed medication and a six-item “concerns” scale to assess beliefs about the danger associated with the use of prescribed medication. Each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (5 points). A necessity-concerns differential was calculated by subtracting the concerns subscale scores from the necessity subscale scores, meaning that higher differential scores indicated higher perceived necessity or lower concerns, thereby representing a lower likelihood of intentional non-adherence. This instrument was cross-culturally adapted to Portuguese in 2013.10

Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension short versionThe short version of the Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH) questionnaire is a 16-item instrument that assesses patients’ global adherence to antihypertensive medication and assesses four adherence-related dimensions: positive attitude toward health care and medication; lack of discipline; aversion toward medication; and active coping with health problems. The MUAH-16 was validated for European Portuguese in 2017.11 This instrument is scaled according to a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”. The final score is obtained by adding the values of each item: In the subscales that accessed positive factors toward adherence to hypertensive medication (subscales I and IV), “totally disagree” responses received 1 point and “totally agree” responses received 7 points; and in the subscales that accessed negative factors toward adherence (subscales II and III), the score was reversed: “totally disagree” responses received 7 points and “totally agree” responses received 1 point.

Data collectionQuestionnaires were administered between February and August 2018 at six Portuguese community pharmacies. Patients were invited to participate in this study if they met the following criteria (visible from the computerized dispensing system): attended one of the participating pharmacies, were older than 18 years and were currently taking at least one antihypertensive drug. The interview was conducted by a trained pharmacist in a private office, where data on personal and family history were collected and the HKT, BMQ and MUAH-16 were administered.

Statistical analysisTo characterize the study population, means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated, as required, for continuous data. Absolute frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. The Shapiro-Wilk (SW) test together with a visual inspection of the Q-Q plot were used to assess the normality of the HKT, BMQ and MUAH-16 scores. Nonparametric tests were used to explore associations between the overall scores on the HKT and BMQ and MUAH-16 scales as well as between their dimensions and with patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

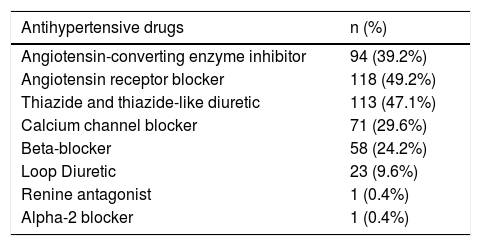

ResultsStudy participantsThere were 240 patients enrolled in the study. The mean age was 64.8 (SD 12.2) years, and 150 (62.5%) were female. The average time since hypertension diagnosis was 12.73 (SD 9.6) years, with a maximum disease duration of 50 years. The mean systolic blood pressure was 135.38 (SD 17.6) mmHg, and the mean diastolic blood pressure was 79.82 (SD 10.6) mmHg, with 55.5% of patients controlled according to the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension.1 The mean number of antihypertensive drugs used was 1.62 (SD 0.99), with 37 (15.4%) patients treated with three or more drugs. A description of the antihypertensive medication used is presented in Table 1.

Patient's antihypertensive medication.

| Antihypertensive drugs | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 94 (39.2%) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 118 (49.2%) |

| Thiazide and thiazide-like diuretic | 113 (47.1%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 71 (29.6%) |

| Beta-blocker | 58 (24.2%) |

| Loop Diuretic | 23 (9.6%) |

| Renine antagonist | 1 (0.4%) |

| Alpha-2 blocker | 1 (0.4%) |

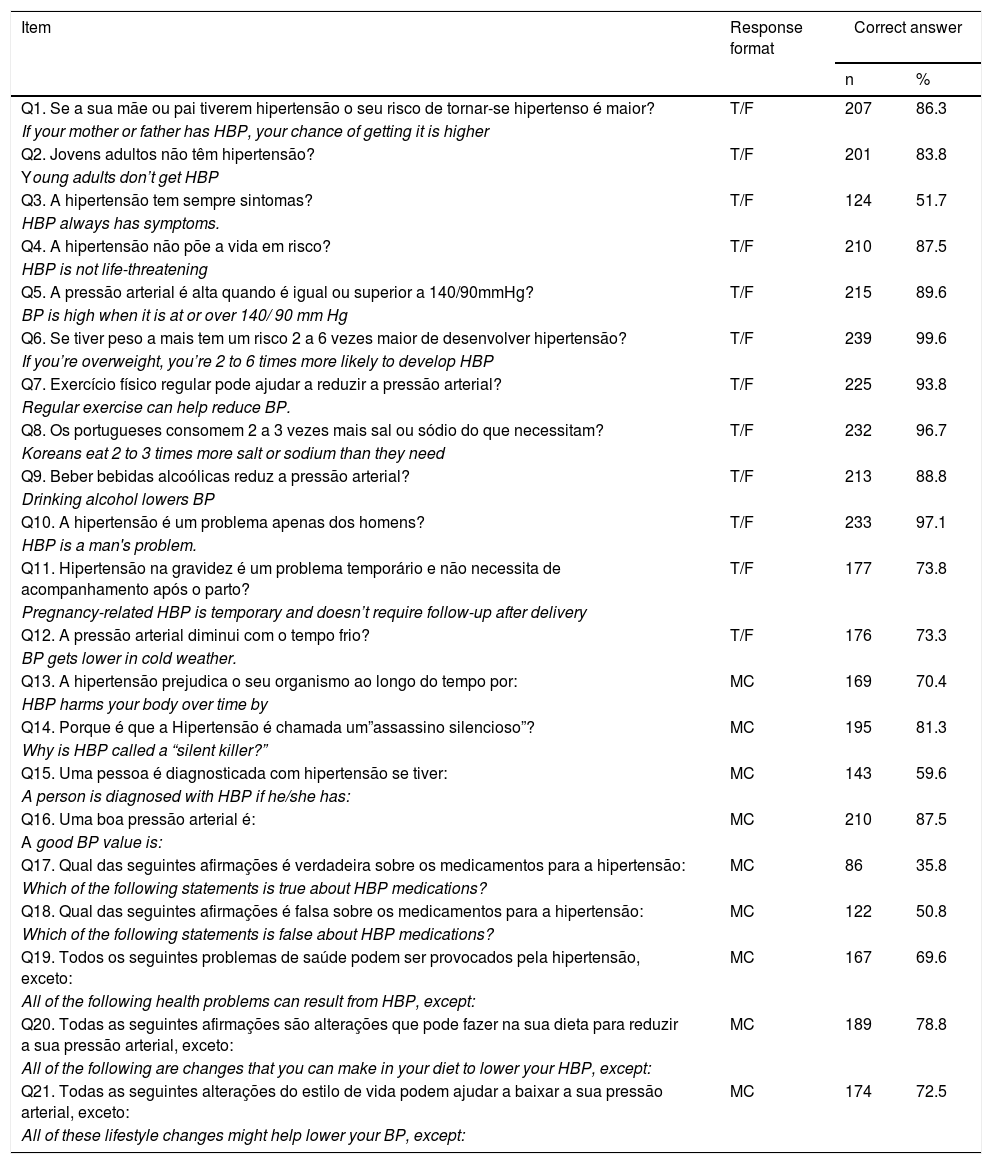

The median score obtained for the HKT was 17.00 (IQR 14-18). Table 2 summarizes the proportion of correct responses to each item. The online appendix presents the answers to the HKT questions. No association was found between patient knowledge about hypertension and patient sex (Mann-Whitney p=0.346), average time since hypertension diagnosis (Spearman p=0.447), blood pressure control (Mann-Whitney p =0.495), or antihypertensive polypharmacy (Kruskal-Wallis p=0.830). However, a negative correlation was found regarding patient age (Spearman's rho=-0.196, p=0.002).

Proportion of correct answers on the Hypertension Knowledge Test (n=239).

| Item | Response format | Correct answer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Q1. Se a sua mãe ou pai tiverem hipertensão o seu risco de tornar-se hipertenso é maior? | T/F | 207 | 86.3 |

| If your mother or father has HBP, your chance of getting it is higher | |||

| Q2. Jovens adultos não têm hipertensão? | T/F | 201 | 83.8 |

| Young adults don’t get HBP | |||

| Q3. A hipertensão tem sempre sintomas? | T/F | 124 | 51.7 |

| HBP always has symptoms. | |||

| Q4. A hipertensão não põe a vida em risco? | T/F | 210 | 87.5 |

| HBP is not life-threatening | |||

| Q5. A pressão arterial é alta quando é igual ou superior a 140/90mmHg? | T/F | 215 | 89.6 |

| BP is high when it is at or over 140/ 90 mm Hg | |||

| Q6. Se tiver peso a mais tem um risco 2 a 6 vezes maior de desenvolver hipertensão? | T/F | 239 | 99.6 |

| If you’re overweight, you’re 2 to 6 times more likely to develop HBP | |||

| Q7. Exercício físico regular pode ajudar a reduzir a pressão arterial? | T/F | 225 | 93.8 |

| Regular exercise can help reduce BP. | |||

| Q8. Os portugueses consomem 2 a 3 vezes mais sal ou sódio do que necessitam? | T/F | 232 | 96.7 |

| Koreans eat 2 to 3 times more salt or sodium than they need | |||

| Q9. Beber bebidas alcoólicas reduz a pressão arterial? | T/F | 213 | 88.8 |

| Drinking alcohol lowers BP | |||

| Q10. A hipertensão é um problema apenas dos homens? | T/F | 233 | 97.1 |

| HBP is a man's problem. | |||

| Q11. Hipertensão na gravidez é um problema temporário e não necessita de acompanhamento após o parto? | T/F | 177 | 73.8 |

| Pregnancy-related HBP is temporary and doesn’t require follow-up after delivery | |||

| Q12. A pressão arterial diminui com o tempo frio? | T/F | 176 | 73.3 |

| BP gets lower in cold weather. | |||

| Q13. A hipertensão prejudica o seu organismo ao longo do tempo por: | MC | 169 | 70.4 |

| HBP harms your body over time by | |||

| Q14. Porque é que a Hipertensão é chamada um”assassino silencioso”? | MC | 195 | 81.3 |

| Why is HBP called a “silent killer?” | |||

| Q15. Uma pessoa é diagnosticada com hipertensão se tiver: | MC | 143 | 59.6 |

| A person is diagnosed with HBP if he/she has: | |||

| Q16. Uma boa pressão arterial é: | MC | 210 | 87.5 |

| A good BP value is: | |||

| Q17. Qual das seguintes afirmações é verdadeira sobre os medicamentos para a hipertensão: | MC | 86 | 35.8 |

| Which of the following statements is true about HBP medications? | |||

| Q18. Qual das seguintes afirmações é falsa sobre os medicamentos para a hipertensão: | MC | 122 | 50.8 |

| Which of the following statements is false about HBP medications? | |||

| Q19. Todos os seguintes problemas de saúde podem ser provocados pela hipertensão, exceto: | MC | 167 | 69.6 |

| All of the following health problems can result from HBP, except: | |||

| Q20. Todas as seguintes afirmações são alterações que pode fazer na sua dieta para reduzir a sua pressão arterial, exceto: | MC | 189 | 78.8 |

| All of the following are changes that you can make in your diet to lower your HBP, except: | |||

| Q21. Todas as seguintes alterações do estilo de vida podem ajudar a baixar a sua pressão arterial, exceto: | MC | 174 | 72.5 |

| All of these lifestyle changes might help lower your BP, except: | |||

Abbreviation: MC=multiple choice; T/F=true or false.

The median score for the BMQ necessity scale was 20.00 (IQR 18-22), the median score for the BMQ concerns scale was 17.00 (IQR 14-21), and the median BMQ necessity-concerns differential was 3.00 (IQR -1-6).

The median score obtained for the MUAH-16 was 79.00 (IQR 69-89). The median scores for the MUAH-16 dimensions were 24.00 (IQR 23-26) for a positive attitude toward health care and medication, 21.00 (IQR 15-25) for lack of discipline, 14.00 (IQR 10-18) for aversion toward medication, and 21.00 (IQR 18-24) for active coping with health problems.

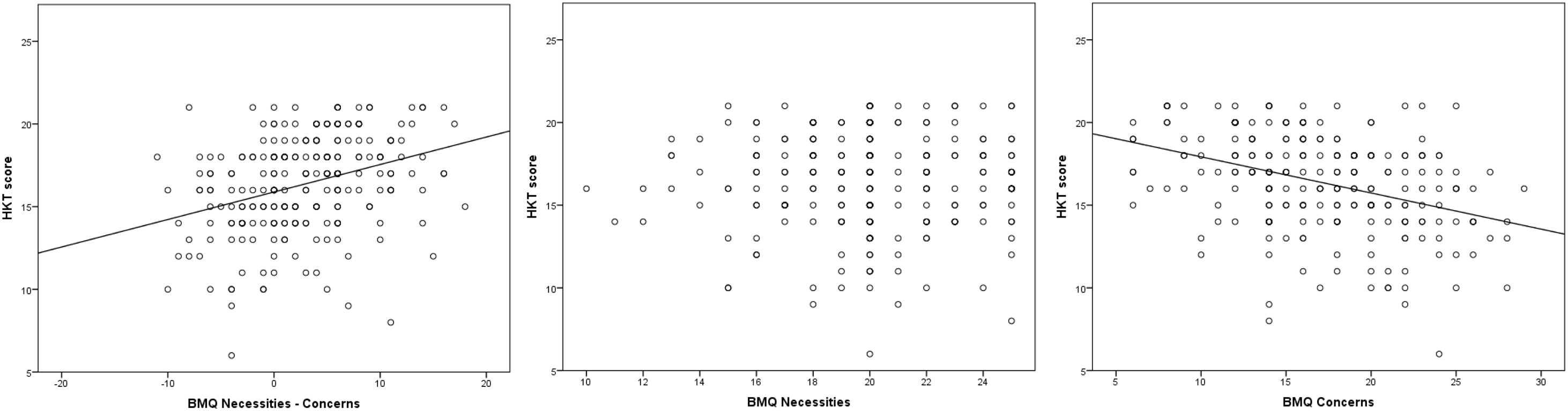

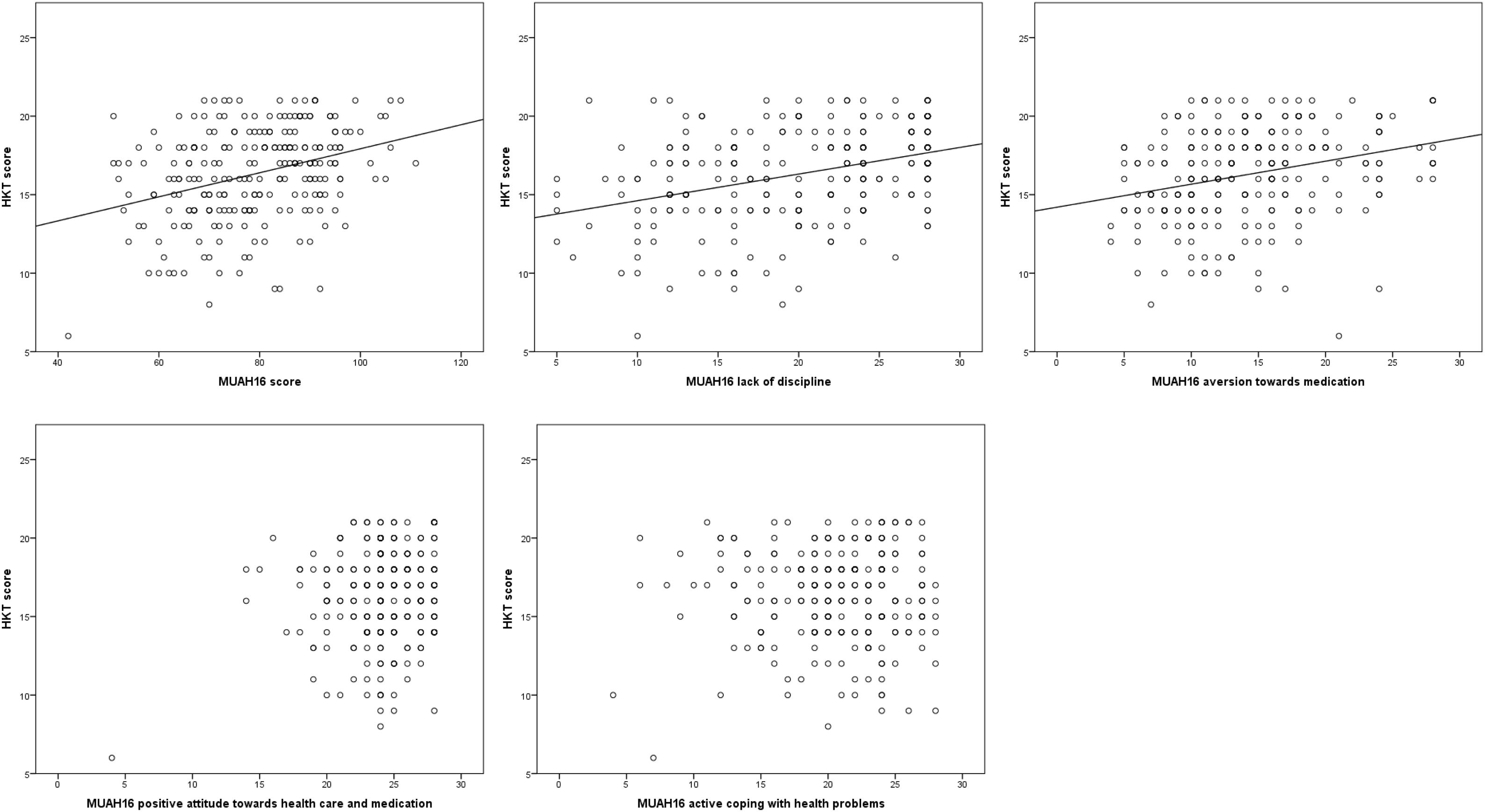

A positive correlation (Spearman's rho=0.357, p<0.001) was found between the HKT score and the BMQ score (resulting in subtraction of the concerns domain from the necessities domain of the BMQ) (Figure 1). Similarly, a positive correlation (Spearman's rho=0.270, p<0.001) was found between the HKT score and the MUAH-16 score (Figure 2). When assessing the association of the HKT score with the two domains of the BMQ (Figure 1), a negative correlation was found with the concerns domain (Spearman's rho=-0.389, p<0.001), while no correlation existed with the necessities domain (p=0.891). Regarding the associations with the MUAH-16 domains (Figure 2), a negative correlation was found between the HKT score and the lack of discipline scores (Spearman's rho=0.353, p<0.001) and with the aversion toward medication scores (Spearman's rho=0.316, p<0.001), while no correlation existed with the positive attitude with health care and medication scores (p=0.250) or with the active coping with health problems scores (p=0.819).

Using the HKT as an instrument to evaluate hypertensive patients’ knowledge of their condition and medication, we found that almost all patients identified overweight, sedentary lifestyle, and salt as risk factors for hypertension, and more than 80% of patients knew the blood pressure therapeutic goals. Conversely, the majority of the patients were unaware of the asymptomatic characteristics of hypertension and believed that antihypertensive treatment had to be used for limited time duration.

Increasing public knowledge and awareness of cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors has become a major goal of healthcare professionals. In 2014, Polonia et al. published the PHYSA study12 and concluded that, in the Portuguese population, the salt intake is almost double the WHO recommendations. These findings had important coverage in mass media, which contributed to the development of national strategies to reduce salt consumption. Different societies established May as the “heart month” and organized campaigns to raise awareness. In 2017, the Portuguese Foundation of Cardiology designed the “The Heart in Sport” campaign, which aimed to promote physical exercise and combat sedentarism.13 In 2018, the Portuguese Society of Cardiology launched the “Capable Heart” campaign to alert the population that cardiovascular diseases (CVD) still lead the list of causes of death in our country and to increase awareness of risk factors for CVD, such as hypertension, obesity and a sedentary lifestyle.14 Since 2018, the Portuguese Society of Hypertension has joined the International Society of Hypertension “May Measurement Month” campaign, which aims to increase the population's awareness of measuring their blood pressure and adopting healthy lifestyle habits.15 However, since 2006, on World Hypertension Day (17 May) the Portuguese Society of Hypertension organizes a campaign to raise awareness about hypertension, which includes screening in several public locations and since 2013, it has created a microsite (www.sphta.org.pt) on its website dedicated to the general public where important information about hypertension is made available, including an extensive questions and answers section.

Using two different instruments, we found an uneven association between hypertension knowledge and components of the beliefs about antihypertensive treatment. Increased knowledge was associated with reduced negative beliefs and attitudes about hypertension and treatment but had no effect on positive beliefs and attitudes.

The BMQ has been used for several different medical conditions: for example, to analyze whether HIV-infected patients’ beliefs regarding their combination antiretroviral therapy and their co-treatments have an impact on their medication adherence16 and to investigate whether beliefs about asthma medication are related to poor asthma control.17 In cardiovascular conditions, the BMQ was used to examine the influence of beliefs about medicines on warfarin adherence among atrial fibrillation patients18 or to examine associations between the beliefs of patients with stroke about stroke and drug treatment and their adherence to drug treatment.19 In our study, we identified a negative correlation between the HKT score and the concerns domain of the BMQ but not with the necessities domain of the BMQ. It seems that higher hypertension knowledge reduced negative beliefs about medication (e.g., “these medicines disrupt my life”) but had no effect on positive beliefs related to patient's perceived needs of medication, e.g., “My life would be impossible without these medicines”).

The MUAH-16 is a promising instrument with less clinical use than BMQ. In our study, the MUAH produced similar results to the BMQ, with a negative correlation between the MUAH and both the lack of discipline domain (e.g., “I find it hard to stick to my daily regimen of medication taking”) and the aversion toward medication domain (e.g., “I dislike taking medication every day”). Similar to the BMQ, no correlation was found between positive attitudes toward health care and medication domains (e.g., “The pros of taking medication weigh up against the cons”) or with active coping with the health problems domain (e.g., “I eat less salt in order to avoid cardiovascular diseases”).

The Health Belief Model was one of the first theories explaining patients’ health behavior and remains one of the most widely recognized in the field. It was developed in the 1950s with the purpose of focusing the efforts of those who sought to improve public health by understanding why people failed to adopt a preventive health measure.20,21 The Health Belief Model theorizes that people's beliefs about whether they are at risk for a disease or health problem and their perceptions of the benefits of taking action to avoid it influence their readiness to take action.22

Our results highlight the potential impact of awareness-raising campaigns in decreasing negative attitudes toward treatment. However, further studies should analyze which health promotion activities are most successful in increasing patients’ perceived need for medication.

Study limitationsThe selection of a sample of hypertensive patients is a limitation of this study, preventing generalization to all Portuguese hypertensive patients.

ConclusionsThere was good patient knowledge regarding the risk factors of hypertension, but questions regarding anti-hypertensive treatment and hypertension symptoms resulted in the most incorrect answers. Assessing the gaps in patients’ knowledge about hypertension would enable the development of more targeted educational activities, leading to better outcomes and improving patient adherence to medication and blood pressure control. By increasing patients’ knowledge about hypertension, it was possible to reduce negative attitudes toward medication, but there was no impact on positive attitudes.

FundingNo external funding was received.

CRediT author statementAna Cabral: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing,

Marta Lavrador: Investigation, Writing - Original Draft - Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing,

Fernando Fernandez-Llimos: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing,

Margarida Castel-Branco: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing,

Isabel Vitória Figueiredo: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing,

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.