Aortic stenosis (AS) is highly age-related, and its prevalence is increasing rapidly in high-income countries.1 Treatment consists of either surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), although the latter is rapidly expanding.2 There are two major types of amyloid protein responsible for cardiac amyloidosis (CA) - transthyretin (TTR) and immunoglobulin lightchain (AL). Previous cohorts report an incidence ranging from nine to 16% for the presence of CA in patients with AS referred for TAVR. These patients appear to have a similar prognosis to those with AS when undergoing TAVR, but a trend toward worse prognosis if left untreated.3 We aimed to investigate the prevalence of CA in patients with severe AS referred for TAVR in the Portuguese population.

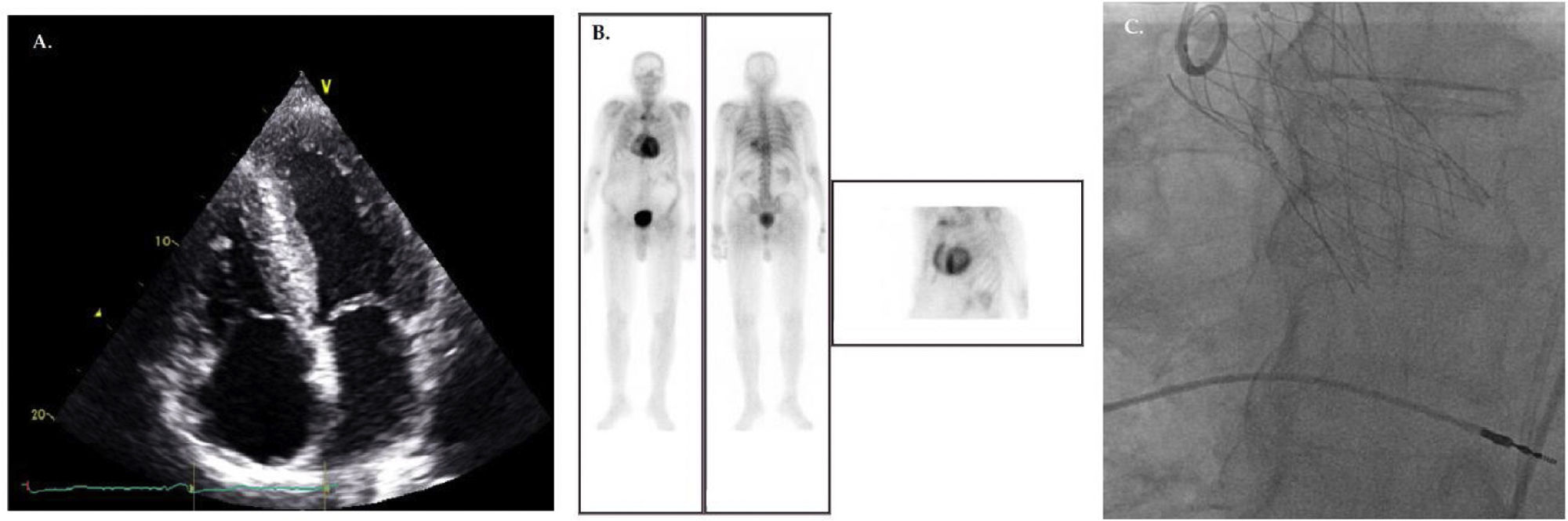

We prospectively recruited 60 consecutive patients referred for TAVR at our tertiary center (Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra) between November 2020 and May 2021. 59 patients agreed to participate and signed an informed consent, approved by the local Ethics Commission. All patients performed coronary angiogram, echocardiogram, thoracic abdominal pelvic CT scan, ECG, bone scintigraphy (99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid [DPD]) and blood and urine monoclonal immunoglobulin testing (Figure 1).

Patient with aortic stenosis and ATTR cardiac amyloidosis before (A, B) and after TAVR (C). (A) Echocardiogram (apical 4-chamber view) shows the characteristic thickening and granular/sparkling appearance of the interventricular septum. (B) DPD scintigraphy illustrating cardiac tracer retention suggestive of cardiac amyloidosis. (C) Fluoroscopy demonstrating the 29-mm NAVITOR™ Transcatheter Valve (Abbott Laboratories, Lake Bluff, Illinois, USA).

About half (54.2%) of patients were male, average age was 82 years and the prevalence of ischemic heart disease and cardiovascular risk factors was high (Table 1). Approximately one third of patients had atrial fibrillation and 27.1% were pacemaker carriers. Echocardiographic baseline findings were: maximum aortic valve gradient 72.77±18.18 mmHg; mean aortic valve gradient 43.49±11.60; aortic valve area 0.65±0.15 cm2; interventricular septum thickness 1.30±0.23 cm; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) 52.06±11.35%; E/E′ 14.63±7.5; tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion 19.2±4 mm; right ventricle/right atrial gradient 38.1±14.32 mmHg.

Patient characteristics of study population.

| Characteristic | AS (n=59) | Lone AS (n=53) | AS+CA (n=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 81.83±6.16 | 81.30±6.19 | 86.5±3.61 | 0.049 |

| Male (%) | 32 (54.2%) | 26 (49.1%) | 6 (100%) | 0.020 |

| Diabetes (%) | 24 (40.7%) | 22 (41.5%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.530 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 41 (69.5%) | 37 (69.8%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0.601 |

| Hypertension (%) | 42 (71.2%) | 38 (71.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0.563 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 21 (35.6%) | 19 (35.8%) | 2 (33.7%) | 0.639 |

| Ischemic heart disease (%) | 25 (42.4%) | 22 (41.5%) | 3 (50%) | 0.507 |

| Pacemaker carrier (%) | 16 (27.1%) | 12 (22.6%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0.041 |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.12±0.61 | 1.13±0.97 | 0.98±0.24 | 0.577 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.75±1.98 | 11.74±2.03 | 11.83±1.64 | 0.911 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 189.69±57.71 | 192.96±58.71 | 160.83±40.93 | 0.199 |

| Leukocytes (×109/L) | 6.63±1.97 | 6.72±2.03 | 5.77±1.01 | 0.263 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139.44±2.80 | 139.47±2.77 | 139.17±3.37 | 0.803 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.35±0.50 | 4.97±11.45 | 39.80±13.50 | 0.598 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| Mean AV gradient (mmHg) | 43.49±11.60 | 43.97±11.45 | 39.80±13.49 | 0.456 |

| AV area (cm2) | 0.65±0.15 | 0.653±0.15 | 0.625±0.15 | 0.727 |

| IV Septum thickness (cm) | 1.30±0.23 | 1.28±0.22 | 1.48±0.18 | 0.065 |

| LEVF (%) | 52.06±11.35 | 53.36±11.92 | 49.60±4.04 | 0.613 |

AS: aortic stenosis; CA: cardiac amyloidosis; AV: aortic valve; IV: interventricular; LEVF: left ejection ventricular fraction.

Cardiac amyloidosis was diagnosed in 6 (10.2%) patients. Perugini grade was 1 (n=3) and 3 (n=3). One patient (Perugini grade=3) was found to have plasma cell dyscrasia, producing monoclonal IgG Kappa protein. CA patients were all male, older (86.5 vs. 81.30 years, p=0.049), more frequently pacemaker carriers (66.7 vs. 22.6%, p=0.041) and had a tendency to have a thicker interventricular septum (1.48 vs. 1.28 cm, p=0.065). TAVR implantation occurred without complications.

We demonstrated that in the Portuguese population, the prevalence of CA in severe AS patients referred for TAVI is in line with that is observed in other countries. This has important consequences for the diagnosis and management of these patients. Although scores and algorithms have been developed for the diagnosis of CA,4 some may not apply in patients with concomitant AS. Recently, the apical sparing phenotype and the LVEF to global longitudinal strain ratio (EFSR), which are considered sensitive and specific parameters for the echocardiographic diagnosis of CA, were shown to be present in a high proportion of patients with severe symptomatic AS without CA.5 Earlier this month, in the biggest prospective study to date including AS and CA patients, a new scoring system for the discrimination between lone AS and AS-CA coexistence was proposed.3

Regarding treatment, in patients with AS and amyloidosis, TAVR is associated with improved outcomes and it should not be viewed as therapeutic futility, as was suggested in the past.3 The diagnosis of CA may also have management implications such as avoidance of beta-blockers, calcium channel antagonists and digoxin; cautious use of angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitors and diuretics; lower threshold for starting anticoagulation and permanent pacing; and consideration of tafamidis in ATTR CA patients.6

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.