Coronary artery fistulas (CAFs) are rare abnormalities, often detected incidentally during invasive coronary angiography (ICA). While most are clinically silent, they can cause significant morbidity. We aimed to investigate the clinical, angiographic and management features of CAFs in a population undergoing ICA.

MethodsWe retrospectively reviewed the data of all ICAs conducted in our department between May 2008 and January 2020 and selected those with CAFs. Clinical, angiographic, therapeutic and follow-up data were obtained from medical records.

ResultsA total of 55 patients with CAFs (35 male, median age 64 years) were identified among 32 174 ICAs. The majority (n=37) had a single fistula. CAFs arose most frequently from the left anterior descending artery (LAD), followed by the right coronary and left circumflex coronary arteries. The most frequent drainage site was the pulmonary artery. Fourteen patients had fistulas originating from both left and right coronary systems. Seven had concomitant congenital cardiovascular disorders. The majority (n=40) were incidental findings. Chest pain was the most common symptom attributable to CAFs and heart murmur the most frequent sign. Conservative management was the main approach (n=40). Eight patients underwent transcatheter closure and seven underwent surgical ligation (six of those during surgery for another heart condition), with no periprocedural mortality.

ConclusionsIn our series, the prevalence of CAFs was 0.2%. The majority originated from the LAD and the pulmonary artery was the main drainage site. In patients undergoing intervention, both percutaneous and surgical techniques were safe and effective.

As fistulas coronárias (FCs) são anomalias raras, detetadas frequentemente de forma incidental durante a angiografia coronária invasiva (ACI). Embora a maioria não cause sintomatologia, podem gerar morbilidade significativa. O nosso objetivo foi descrever as características clínicas e angiográficas das FCs detetadas numa população submetida a ACI, assim como o tratamento realizado.

MétodosForam retrospetivamente revistos os dados de todas as ACIs realizadas no nosso Centro de maio de 2008 a janeiro de 2020 e selecionadas as que descreviam FCs. Os dados clínicos, angiográficos, terapêuticos e de follow-up foram obtidos de registos informáticos.

ResultadosEntre 32 174 coronariografias, identificámos 55 doentes com FCs (35 homens, idade média 64 anos). A maioria (n=37) tinha uma fístula única. A origem mais frequente foi da artéria coronária descendente anterior (DA), seguido da artéria coronária direita e circunflexa. O local de drenagem mais frequente foi a artéria pulmonar. Catorze doentes tinham fístulas originadas da artéria coronária esquerda e direita. Sete tinham doenças cardiovasculares congénitas concomitantes. A maioria (n=40) foi descoberta incidentalmente. O sintoma e sinal mais frequentes foram a dor torácica e o sopro cardíaco. A abordagem terapêutica foi maioritariamente conservadora (n=40). Oito doentes realizaram encerramento percutâneo e sete tratamento cirúrgico (dos quais seis durante cirurgias por outra patologia cardíaca), sem mortalidade periprocedimento.

ConclusõesA prevalência de FCs na nossa série foi de 0,2%. A maioria originou-se da DA, sendo a artéria pulmonar o local de drenagem mais frequente. Em doentes submetidos a intervenção, tanto as técnicas percutâneas como cirúrgicas foram seguras e eficazes.

Coronary artery fistulas (CAFs) are abnormal communications between one or more coronary arteries and another blood vessel or cardiac chamber, bypassing the myocardial capillary network.1,2 These rare coronary abnormalities have an estimated prevalence of 0.002% in the general population and are detected in 0.1-0.8% of adult patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, often as an incidental finding.2–4 While most are clinically silent, they can cause significant morbidity in any age group.

ObjectivesAngiographic characteristics of CAFs in Portuguese patients have not been previously described. In this study, we aimed to investigate the clinical and angiographic characteristics of CAFs in a population of Portuguese patients undergoing invasive coronary angiography (ICA), as well as their assessment and management strategies.

MethodsWe retrospectively reviewed the data of all invasive coronary angiographies conducted in our invasive cardiology department between May 2008 and January 2020 and selected those which reported the presence of at least one CAF. Clinical, angiographic, therapeutic and follow-up data were obtained from medical records. All data were anonymized before processing. Coronary angiography images were reviewed by two interventional cardiologists and CAFs were classified according to their origin and drainage sites. Significant atherosclerotic coronary artery disease was defined as ≥70% luminal stenosis in epicardial coronary arteries or their main branches. Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

ResultsA total of 55 (0.2%) patients with CAFs were noted among 32 174 coronary angiographies performed during the selected period. Of these, 63.6% (n=35) were male, with ages between 5 and 85 years and a median age of 64 years. The median follow-up was six years (0-11 years). In seven patients, follow-up was not possible due to the absence of medical records.

The majority of patients had a single fistula (n=37, 67.3%), 12 patients had two fistulas (21.8%), one had three fistulas (1.8%), one had four (1.8%), and four patients had multiple microfistulas (plexiform vessel network) (7.3%). Fistulas originating from both left and right coronary systems were found in 25.5% of patients (n=14).

CAFs arose most frequently from the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (n=32), followed by the right coronary (n=19) and left circumflex (n=16) arteries. Left main (n=7) and intermediate coronary arteries (n=1) were less common origin sites. The most frequent drainage sites were the pulmonary artery (n=43), left ventricle (n=12), right atrium (n=7) and pulmonary vascular bed (n=7).

The majority of CAFs were incidental findings (n=40; 72.7%) and were considered not to be responsible for patients’ symptoms or signs. In the remaining patients (n=15; 27.3%), CAFs were diagnosed during assessment of a heart murmur (n=8), chest pain (n=6) or exertional dyspnea (n=1). In these cases, the fistula was considered to be the main cause of the patients’ symptoms or signs. The reasons that prompted the initial ICA are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Our study population is heterogeneous and included pediatric patients (n=7), patients with congenital cardiovascular anomalies (n=7) and patients who had previously undergone cardiac surgery (n=6).

In the pediatric population (n=7), the majority of CAFs (n=5) were detected during the investigation of a heart murmur and, in these patients, the CAF had already been diagnosed or suspected on the transthoracic echocardiogram conducted before ICA.

Concomitant congenital cardiovascular anomalies were present in seven patients (12.7%): isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) (n=2); ostium secundum atrial septal defect and pulmonary stenosis (PS) (n=1); bicuspid aortic valve (n=1); hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n=1); transposition of the great vessels (TGV), ventricular septal defect and PS (n=1); and aortic coarctation, anomalous origin of the left circumflex artery from the right coronary artery and subaortic membrane (n=1). Of these patients, four had already undergone open heart surgery for correction (one Rastelli procedure for TGV, one surgical correction of ostium secundum ASD and PS, one ostium secundum ASD and one subaortic membrane resection plus aortic coarctation correction).

Six patients (10.9%) had a history of cardiac surgery: one heart transplantation, one coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and aortic/mitral valve replacement surgery, and the four operations for congenital heart disease listed above. Regarding the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, 41.8% of patients had hypertension (n=23), 29.1% had type 2 diabetes (n=16), 56.3% had dyslipidemia (n=31), 9.1% were obese (n=5) and 25.5% were current or former smokers (n=14).

Regarding the choice of treatment, medical treatment or watchful waiting was applied in patients with small shunts and no symptoms. Excluding patients who underwent surgery primarily due to other cardiac conditions, intervention was conducted in patients with symptoms, together with evidence of ischemia or cardiac chamber volume overload on noninvasive assessment. In the asymptomatic patients, intervention was due to the large size of the fistulas (the largest with an aneurysmal proximal segment of 70 mm) associated with a significant shunt (pulmonary to systemic blood flow ratio [Qp/Qs] >1.5) or evidence of ischemia. The smallest fistula undergoing intervention had a caliber of approximately 2.5 mm, in a symptomatic patient with associated ischemia on noninvasive assessment.

Of the group in which the fistula was considered as the probable cause of the patients’ clinical findings (due to either symptoms or the presence of a heart murmur [n=15]), nine underwent intervention (60%): eight patients with transcatheter closure (TCC) and one patient with surgical ligation. In the patient who underwent surgery specifically for fistula closure, percutaneous treatment was not technically feasible. The devices used in TCC were the Amplatzer Vascular Plug II® (n=3), the Amplatzer Vascular Plug IV® (n=1), the Medtronic MVP-3Q Micro Vascular Plug® (n=2), the Amplatzer Septal Occluder® (n=1) and the Amplatzer Ductal Occluder® (n=1).

The other patients in this group (n=6) remained on watchful waiting or medical therapy. Four of them had neither significant shunt (as assessed by Qp/Qs) nor evidence of ischemia or volume overload, and two patients with chest pain had anatomies in which TCC was not technically feasible and became asymptomatic with anti-ischemic therapy.

In the group of patients in which the fistula was considered as an incidental finding (n=40), conservative management was the main approach. Six patients underwent intervention (15%), all of them during surgery for another primary cardiac condition.

In both groups of patients undergoing intervention, there was no periprocedural mortality. One patient undergoing TCC developed postprocedural myocardial infarction and pericarditis. In the other patients, there were no procedure-related complications immediately or during follow-up. Considering the patients whose symptoms were attributed to CAFs, all showed clinical improvement after the procedure.

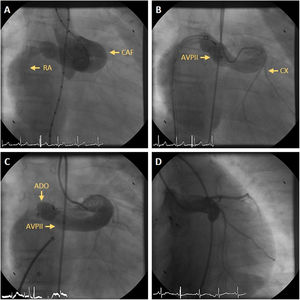

In the patients who underwent TCC, acute procedural success with no or trivial residual flow occurred in four (50%) CAFs. Residual flow was small in three (37.5%) and large in one (12.5%). The four patients with residual flow had a follow-up angiography at a median of 109 days (9-167 days). Of these, two had no residual flow and a small residual flow persisted in two. One of these patients, who had previously undergone TCC with an Amplatzer Vascular Plug II® device, had a reintervention with implantation of an Amplatzer Ductal Occluder® device, which was successful and without complications (Figure 1 and Supplementary Videos). The other remained in follow-up and underwent another ICA one year later, which showed complete occlusion of the CAF.

(A) Aortogram showing a coronary artery fistula (CAF) from the left main coronary artery to the right atrium (RA); (B) selective injection in the left main coronary artery after implantation of an Amplatzer Vascular Plug II® (AVPII) device in the CAF, with residual flow via two orifices to the RA; (C) a second device, an Amplatzer Ductal Occluder® (ADO), was implanted in the inferior orifice; (D) follow-up angiography nine months later revealing complete closure of the CAF after the emergence of the circumflex artery (CX).

Postprocedural antithrombotic strategy was mostly decided on a case-by-case basis. Most patients were treated with dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for one month, followed by aspirin alone for six months. Two pediatric patients were treated with warfarin for six months after TCC due to the large size of the fistulas at their proximal ends. Some patients continued antithrombotic therapy beyond six months at the discretion of the physician. Antithrombotic strategy for patients who had their CAFs closed during surgery for another major heart condition was mainly guided by the primary reason for cardiac surgery.

Data from patients who underwent intervention are summarized in Table 1. Supplementary Table 1 describes all patients from our series.

Characteristics of patients with coronary artery fistulas submitted to intervention.

| Gender, age at diagnosis | Prior medical history | Fistula course | Symptoms/findings when discovered | Fistula management | Complications and follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F, 69 | Type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, aortic stenosis | LMCA-PA; proximal LAD-PA; two from proximal RCA-PA | Incidental finding in preoperative assessment of AV disease | Surgical AV replacement and SL of the fistulas | Uneventful |

| F, 61 | Hypertension, dyslipidemia; surgical correction of ostium secundum ASD; AF | Mid RCA-right atrium; proximal LCX-right atrium | Heart murmur | TCC of RCA-right atrium fistula; watchful waiting of the other fistula | Uneventful |

| M, 66 | Type 2 diabetes, hypertension | LMCA-PA | NSTEMI and cardiac arrest | TCC | Died one year later in the postoperative period of knee surgery, undefined cause |

| M, 55 | Dyslipidemia, smoking | Proximal LCX-PA | Incidental finding because of NSTEMI (LAD and LCX stenosis) | CABG and SL of the fistula | Uneventful |

| M, 55 | Dyslipidemia | Proximal RCA-PA | Exertional chest pain; positive exercise ECG and stress CMR perfusion | TCC | Uneventful; symptom improvement |

| F, 75 | Hypertension | Proximal RCA-pulmonary vascular bed | Incidental finding in preoperative assessment of AV disease | Surgical AV replacement and SL of the fistula | Uneventful |

| F, 69 | Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia; PAD; CKD on hemodialysis | Proximal LAD-PA | Incidental finding during assessment of stable angina (obstructive three-vessel disease) | CABG, surgical AV replacement and SL of the fistula | Died four years later of pyelonephritis |

| M, 64 | Type 2 diabetes, smoking; bicuspid AV | Mid LAD-PA | Incidental finding in preoperative assessment of AV disease | Surgical AV replacement and SL of the fistula | Uneventful |

| F, 15 | None | LMCA-right atrium | Heart murmur | TCC | Uneventful; follow-up ICA with complete fistula occlusion from the device |

| F, 10 | None | LMCA-right atrium | Heart murmur | TCC | Underwent reintervention (TCC) one year later, no residual shunt. |

| F, 42 | Obesity | Proximal LAD-PA | Exertional chest pain | TCC | Uneventful; symptom improvement |

| F, 70 | Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia | Proximal LAD-PA; proximal RCA-PA | Incidental finding in preoperative assessment of AV disease | Surgical AV replacement and SL of the fistulas | Lost |

| M, 5 | None | Proximal RCA-right atrium | Heart murmur; dilated right cardiac chambers | TCC | Uneventful |

| M, 60 | None | Mid LAD-RV; proximal LCX-right atrium; proximal RCA-right atrium | Exertional dyspnea (NYHA class III); dilated right cardiac chambers; pulmonary hypertension | SL of the fistula | Dyspnea improvement; developed atrial fibrillation one year after surgery |

| M, 37 | None | RCA-superior vena cava | Heart murmur; positive nuclear stress test | TCC | Uneventful |

AF: atrial fibrillation; ASD: atrial septal defect; AV: aortic valve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance; ECG: electrocardiogram; F: female; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX: left circumflex coronary artery; LMCA: left main coronary artery; M: male; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PA: pulmonary artery; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; RCA: right coronary artery; RV: right ventricle; SL: surgical ligation; TCC: transcatheter closure.

We retrospectively assessed 55 patients diagnosed as having at least one CAF in our catheterization laboratory between May 2008 and January 2020 in terms of clinical and angiographic features, diagnostic methods and treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale single-center retrospective study investigating CAFs in Portuguese patients.

Epidemiology, anatomy and etiologyCAFs are infrequent abnormalities of coronary artery termination. In our angiographic series, the prevalence of CAFs was 0.2%.

Although in earlier studies CAFs were most often described as involving the right coronary artery, more recent studies have found CAFs to arise most frequently from the LAD.2–4 The most commonly reported drainage site is the pulmonary artery.2,4,5 As in those studies, most CAFs in our series originated from the LAD and the most common pattern was between the LAD and the pulmonary artery.

Drainage of CAFs into the left heart chambers has been reported as a very rare finding.2 However, in our series the left ventricle was the second most common drainage site, either in the form of one or more distinct small channels or as multiple microfistulas. Canga et al.4 also reported the left ventricle as the second most common drainage site in their series.

While CAFs are most commonly congenital, they can be acquired, as in the setting of infective endocarditis or chest trauma. Although rarely reported, acquired CAFs can also be iatrogenic, occurring after procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG, valve replacement, permanent pacemaker implantation and endomyocardial biopsy.1 Chiu et al.6 described an incidence of 0.44% of acquired CAFs after open heart surgery for congenital heart disease.

In our study, 10.9% of patients (n=6) had a history of open cardiac surgery. In one of those patients, who had undergone CABG and aortic/mitral valve replacement surgery, the fistula was considered to be clearly iatrogenic, since it was not present in the preoperative ICA. In the four patients who had undergone previous open cardiac surgery for correction of congenital heart disease, the fistula could also have been iatrogenic, but we cannot state this with certainty as these patients had not undergone a previous ICA for comparison. In the patient with a heart transplant, as all the endomyocardial biopsies were performed in the right ventricle and the fistula was from the distal LAD to the left ventricle, we could not find a direct cause-effect relationship.

Congenital CAFs occur most frequently as an isolated anomaly, but they can be associated with another congenital heart disease in 10-45% of cases.1 Concomitant congenital cardiovascular disorders were present in 12.7% of the patients in our series, the most frequent being atrial septal defect.

The observed high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among this population is probably explained by the fact that CAFs were detected incidentally in a large number of cases during a coronary angiography performed due to suspected atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (acute coronary syndromes or assessment of stable angina).

Clinical presentationThe clinical presentation of CAFs is mainly determined by the shunt volume, site, duration and the presence of underlying cardiac disease. Most CAFs are clinically silent.7 However, volume overload of both ventricles or solely of the left chambers (depending on the drainage site) can result in heart failure, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and pulmonary hypertension. Fistulas can also give rise to the coronary steal phenomenon, which causes ischemia by diverting blood from the high-resistance myocardial capillary bed into the low-resistance fistula and by preventing coronary flow reserve from increasing during exercise.7 Dilatation of the fistula and affected coronary artery can occur with time and give rise to complications such as local compression or rupture.

Clinical presentations include congestive heart failure, chest pain and palpitations, while a soft continuous murmur (crescendo-decrescendo in both systole and diastole) is the most commonly reported physical examination finding in CAF patients.5,8 Presentation can also be related to complications such as myocardial infarction, infective endocarditis and rupture or thrombosis of a fistula or an associated aneurysm.5,9 Premature coronary atherosclerosis has also been reported.7

Regarding the 15 patients in our series in whom CAFs were considered to be the main cause of the patient's clinical status, chest pain was the most common symptom (40%), while heart murmur was the most frequent sign (53.3%). As for the other patients, in whom fistulas were considered to be an incidental finding (n=40), symptoms are difficult to discern due to the presence of concomitant disease which might explain them, particularly obstructive coronary disease or valvular heart disease.

In patients with acute coronary syndromes and concomitant coronary fistulas, the relationship with the fistula is also difficult to ascertain. Responsible mechanisms may be thromboembolic complications due to turbulent flow in the fistulous vessel and/or hypoperfusion of the related main coronary artery.10 In one patient in our series, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction was considered to be directly attributed to a large left main-pulmonary artery fistula. In the other cases of acute coronary syndrome, the contribution of the fistulas was less certain.

Diagnostic techniquesCardiac catheterization with coronary angiography remains the gold standard for detecting CAFs,1 also providing hemodynamic and shunt calculation data. In this series, coronary angiography was the standard for diagnosis in all patients, and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) was performed in cases in which additional information on the fistula anatomy was needed. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and MDCT can provide further details when the CAF anatomy is difficult to discern by ICA.11 In particular, MDCT provides detailed information on the anatomy of the coronary arteries and fistulas, the patency of the shunt and the relationship with adjacent structures, and also enables assessment of the venous system. CAF prevalence has been reported to be higher in MDCT-based series than in ICA series.12,13

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) can detect CAFs but is often unable to delineate the fistula pathway, which could be improved with the use of transesophageal echocardiography.14,15 Even so, TTE remains vital for assessment of chamber size, systolic function and segmental contractility, as for investigation of associated cardiac anomalies.

Exercise electrocardiography and myocardial perfusion imaging or CMR can be valuable tools for the assessment of myocardial ischemia. However, it has been reported that stress testing with vasodilators could lead to negative results for ischemia due to the poor vasodilatory capacity of the fistula compared to the native coronaries, favoring flow in the original feeding vessel.7 Positron emission tomography scanning can be of great value as a non-invasive diagnostic technique to assess flow ratios of the different coronary arteries and to quantify myocardial perfusion reserve,10 but it was not applied in our patients.

ManagementThe optimal management of CAFs remains controversial. Treatment options include TCC, surgical ligation and pharmacological treatment with follow-up over time. Recently, it has also been demonstrated that radiofrequency ablation may be applied for the closure of CAFs.16,17 The decision depends on the patient's age and symptoms as well as the anatomic and functional characteristics of the fistula and the risk of future complications. While it is clear that hemodynamically significant fistulas do require intervention, there is no agreement on the ideal management of small and/or asymptomatic fistulas. Regarding children, elective closure of any clinically apparent CAF after 3-5 years of age should be performed, even if the patient is asymptomatic.18 Algorithms for assessment and treatment of patients with CAFs have recently been suggested by Karazisi et al. and Buccheri et al.1,7

In our series, watchful waiting was the main approach. TCC was performed in eight patients and cardiac surgery was performed specifically for fistula closure in one patient. Six other patients had their fistulas closed during cardiac surgery for another cause. In the pediatric population undergoing intervention, percutaneous closure was conducted in all cases.

When intervention is indicated, catheter-based interventional techniques have become the preferred option in the current era, if technically feasible.9,19,20 On the other hand, surgical ligation is indicated in distal fistulas, large, high-flow fistulas, multiple complex communications, tortuous arteries, prominent aneurysms, a wide drainage site, presence of large vascular branches that can be accidentally embolized, or if the patient has associated cardiac lesions that need surgical correction.1 Both surgical and percutaneous techniques have been associated with good outcomes and a low risk of complications and seem to be equally effective.2,20,21,22 Nevertheless, periprocedural mortality and complications such as myocardial infarction have been reported.21 Among the 15 patients who underwent intervention in our series, there was one case of myocardial infarction and pericarditis immediately after TCC. There were no periprocedural deaths or procedure-related complications during follow-up. One patient needed a percutaneous reintervention due to persistent residual flow in the fistula.

Concerning pharmacological treatment, this generally includes antianginal therapy addressing the demand and supply mismatch induced by the coronary steal phenomenon and antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy in selected cases. Although not endorsed by current guidelines, most authors recommend prophylaxis against bacterial endocarditis regardless of the type of fistula.1,7,8,18,21

ConclusionsIn our series, the prevalence of CAFs was 0.2%, most of them detected incidentally. The majority originated from the left coronary system and the pulmonary artery was the main drainage site. Although most patients had a single fistula, multiple fistulas were not uncommon. In the 15 patients who underwent intervention, both percutaneous and surgical techniques were safe and effective.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.