Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers (beta-blockers) are frequently used for patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), although evidence-based recommendations for this indication are still lacking. Our goal was to assess which clinical factors are associated with the prescription of beta-blockers in patients discharged after an episode of HFpEF decompensation, and the clinical outcomes of these patients.

MethodsWe assessed 1078 patients with HFpEF and in sinus rhythm who had experienced an acute HF episode to explore whether prescription of beta-blockers on discharge was associated with one-year all-cause mortality or the composite endpoint of one-year all-cause death or HF readmission. We also examined the clinical factors associated with beta-blocker discharge prescription for such patients.

ResultsAt discharge, 531 (49.3%) patients were on beta-blocker therapy. Patients on beta-blockers more often had a prior diagnosis of hypertension and more comorbidity (including ischemic heart disease) and a better functional status, but less often a prior diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These patients had a lower heart rate on admission and more often used angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors and loop diuretics. One year after the index admission, 161 patients (15%) had died and 314 (29%) had experienced the composite endpoint. After multivariate adjustment, beta-blocker prescription was not associated with either all-cause mortality (HR=0.83 [95% CI 0.61-1.13]; p=0.236) or the composite endpoint (HR=0.98 [95% CI 0.79-1.23]; p=0.882).

ConclusionIn patients with HFpEF in sinus rhythm, beta-blocker use was not related to one-year mortality or mortality plus HF readmission.

Os bloqueadores dos recetores β-adrenérgicos (bloqueadores-β) são frequentemente utilizados nos doentes com insuficiência cardíaca (IC) com fração de ejeção preservada (IC-FEp), embora ainda escasseiem as recomendações baseadas na evidência para essa indicação. O nosso objetivo foi avaliar que fatores clínicos estão associados à prescrição de β-bloqueadores em doentes com alta após um episódio de descompensação por IC-FEp e os outcomes destes doentes.

MétodosAvaliámos 1078 doentes com IC-FEp em ritmo sinusal após um episódio de IC aguda para avaliar se a utilização de bloqueadores-β no momento da alta se associou à mortalidade global ao fim de um ano ou ao endpoint composto de mortalidade global ao fim de um ano ou reinternamento por IC.

ResultadosNo momento da alta, 531 (49,3%) doentes estavam medicados com bloqueadores-β. Estes doentes apresentaram mais frequentemente um diagnóstico prévio de hipertensão e mais comorbilidades (incluindo doença cardíaca isquémica) e um melhor status funcional, mas com menor frequência um diagnóstico prévio de doença pulmonar obstrutiva crónica. Apresentaram também uma frequência cardíaca mais baixa no momento do internamento e foram tratados mais frequentemente com inibidores da enzima de conversão da angiotensina, bloqueadores dos recetores de angiotensina, inibidores dos recetores de angiotensina-neprilisina e diuréticos de ansa. Um ano após a admissão-índice, 161 doentes (15%) tinham morrido e 314 (29%) tinham atingido o objetivo composto. Após análise multivariada, a indicação para bloqueadores-β não se associou nem ao endpoint primário s [HR=0,83 (CI 95%: 0,61-1,13); p=0,236] nem ao composto [HR=0,98 (CI 95%: 0,79-1,23); p=0,882].

ConclusãoEm doentes com IC-FEp em ritmo sinusal, a utilização de bloqueadores-β não se associou à redução da mortalidade global a um ano nem à redução de mortalidade global e reinternamento por IC.

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) increases with age and is higher in females across the spectrum of old age.1,2 Currently, no treatment has been shown to improve the prognosis of HFpEF.3,4 This lack of evidence has not prevented these patients’ attending physicians from prescribing therapies with benefits proven only for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), especially when other comorbidities appear to provide a justification for their use.

The use of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers (beta-blockers) is therefore common in patients with HFpEF, although scientific doubts about their benefits have been raised.3,5,6 Controlled studies assessing the clinical effects of beta-blockers in HFpEF have shown inconsistent and heterogeneous results.7–9 However, data from current registries show high rates (ranging from 50% to 80%) of beta-blocker prescription in these patients, regardless of baseline heart rhythm.10,11 In our setting, in the RICA registry, which assesses the characteristics and trajectories of elderly HF patients (mean age 80 years) cared for by internists during an episode of decompensation, the percentage of beta-blocker prescription on discharge was 53%, with a sizable proportion of such patients also suffering from atrial fibrillation (AF).12

To analyze the clinical effect of beta-blockers in elderly patients with HFpEF in more detail, avoiding the confounding effect of age-prevalent concomitant arrhythmias, we investigated whether this class of drugs modifies the risk of mortality or readmission after an acute episode of HF decompensation focusing only on the subset of HFpEF patients presenting with sinus rhythm on admission.

MethodsStudy design and populationThe patients analyzed in this study were included in the RICA national HF registry, coordinated by the Heart Failure Working Group of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. RICA is a multicenter prospective registry that includes patients consecutively admitted for acute HF (AHF) in 52 Spanish hospitals.12

The registry includes all patients aged 50 years or older admitted because of AHF, according to the diagnostic criteria of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).4 Patients who die during the index admission are excluded from the registry. For the purpose of this study, we selected only patients admitted between March 2008 and March 2020, with (a) well-documented HFpEF (clinical HF criteria plus echocardiographic data fulfilling the current ESC criteria for HFpEF plus elevated N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP] when available), and (b) electrocardiogram-proven sinus rhythm at the time of admission and no prior history of AF. The number of patients with recovered LVEF (prior echocardiographic data were missing in most patients) was likely anecdotal.

Variables analyzedPatients’ data are recorded in detail through a website (https://www.registrorica.org). They include sociodemographic data, disease history, comorbidity burden, ability to perform basic activities of daily living, cognition, admission clinical data (blood pressure, heart rate, weight, height and body mass index, characteristics of the AHF episode, provoking factors) and discharge HF-related medications. Consultant cardiologists assess patients’ LVEF; a recent two-dimensional echocardiogram (performed either during the index admission or within the three previous months) is mandatory for inclusion in the registry. A complete blood count and a biochemistry panel including renal function, lipid profile, glucose, uric acid, troponin T, and NT-proBNP are also collected and recorded. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation and the presence of chronic kidney disease is coded when eGFR is ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Main endpointsPatients with HFpEF were divided into two groups according to whether or not they were discharged with a prescription of any beta-blocker with a guideline-recommended use for chronic HFrEF (carvedilol, bisoprolol, metoprolol succinate, or nebivolol) regardless of dose.4 The primary endpoints of our study were one-year all-cause mortality (after index admission discharge) and the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF readmission.

EthicsThe study complied with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol (155/2007) was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Reina Sofia in Cordoba, Spain. All patients provided written informed consent at inclusion.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the sample was performed using mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. The baseline characteristics of the groups were compared using the t test and Fisher's exact test for quantitative and categorical variables, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of beta-blocker prescription at discharge. Mortality and readmission were analyzed at one-year follow-up, and predictive differences between groups were analyzed with cumulative episode curves using the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was carried out to asses mortality risks, using the backward conditional method for all variables shown in univariate analysis to be significantly associated with a higher probability of readmission or death. The covariates included in the final multivariate model were those associated with statistical significance in univariate analysis in addition to those related to the use of beta-blockers. The C-statistic of the final model was 0.664. A similar analysis was performed to analyze the combination of overall mortality or HF readmission. The C-statistic of this other final model was 0.626. The level of statistical significance was established as p<0.05. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS, version 21.0, Armonk, NY, USA.

ResultsOf the total of 5312 RICA patients, 3315 fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and of these, 2042 had HFpEF (61.6%). Of these, 1078 (52.8%) were in sinus rhythm and were included in this study. At the time of hospital discharge, 531 (49.3%) were on beta-blocker therapy; 289 (54%) patients received bisoprolol, 43 (27%) carvedilol, 51 (9.6%) nebivolol, seven (1.2%) metoprolol succinate, and 8.1% others.

The mean age at inclusion was 79.3±8.8 years, and 419 (39%) were male. The baseline characteristics of these patients and the differences according to discharge beta-blocker use are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants.

| Overall (n=1078) | Beta-blockers (n=531) | No beta-blockers (n=547) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 79.3 (8.8) | 78.9 (8.9) | 79.7 (8.7) | 0.136 |

| Male, n (%) | 419 (39%) | 207 (39%) | 212 (39%) | 0.950 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.4 (10.0) | 30.3 (6.0) | 30.5 (12.7) | 0.713 |

| Comorbidities and HF etiology | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 975 (90%) | 493 (93%) | 482 (88%) | 0.009 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 619 (57%) | 328 (62%) | 291 (53%) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 546 (51%) | 283 (53%) | 263 (48%) | 0.088 |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 635 (59%) | 320 (60%) | 315 (58%) | 0.386 |

| PAD, n (%) | 132 (12%) | 68 (13%) | 64 (12%) | 0.642 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 136 (13%) | 71 (13%) | 65 (12%) | 0.465 |

| CKD, n (%) | 642 (60%) | 327 (62%) | 315 (58%) | 0.193 |

| Dementia n (%) | 48 (4.5%) | 20 (3.8%) | 28 (5.1%) | 0.304 |

| COPD, n (%) | 252 (23%) | 92 (17%) | 160 (29%) | <0.001 |

| Charlson index, n (%) | 3.1 (2.5) | 3.3 (2.6) | 2.8 (2.4) | 0.001 |

| Barthel index, n (%) | 81.3 (23.3) | 83.4 (22.1) | 79.2 (24.3) | 0.003 |

| Pfeiffer test, n (%) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.5 (2.0) | 0.654 |

| Ischemic HF etiology, n (%) | 240 (23%) | 166 (32%) | 74 (14%) | <0.001 |

| Valvular HF etiology, n (%) | 163 (15%) | 68 (13%) | 95 (18%) | 0.034 |

| Initial assessment | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 146.2 (29.2) | 147.6 (29.3) | 144.8 (29.0) | 0.113 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74.7 (16.1) | 74.8 (16.0) | 74.6 (16.3) | 0.868 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 81.2 (17.3) | 79.5 (17.8) | 82.9 (16.7) | 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 11.8 (2.0) | 11.6 (2.1) | 11.9 (2.0) | 0.055 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 144.4 (72.0) | 146.0 (71.2) | 142.9 (72.8) | 0.503 |

| Urea, mg/dl | 69.3 (36.2) | 69.5 (36.0) | 69.1 (36.5) | 0.865 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.500 |

| eGFR MDRD, ml/min/m2 | 56.9 (26.6) | 55.8 (26.0) | 57.9 (27.1) | 0.184 |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 138.8 (4.9) | 138.8 (4.8) | 138.9 (5.0) | 0.682 |

| Potassium, mmol/l | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.7) | 0.814 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 7.7 (2.3) | 7.8 (2.4) | 7.6 (2.3) | 0.400 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 155.2 (44.0) | 143.3 (46.1) | 174.2 (36.8) | 0.211 |

| BNP, pg/ml | 906.9 (2084.9) | 990.0 (2404.3) | 804.8 (1628.2) | 0.650 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 6019.5 (23 082.6) | 5832.4 (7605.8) | 6231.0 (32 746.3) | 0.862 |

| High troponin, % | 5 (1.50%) | 1 (0.62%) | 4 (2.3%) | 0.372 |

| CA 125, U/ml | 50.6 (69.6) | 44.1 (53.7) | 57.3 (82.8) | 0.251 |

BMI: body mass index; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; CA 125: serum cancer antigen 125; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; eGFR MDRD: estimated glomerular filtration rate by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula; HF: heart failure; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Treatment at discharge and outcomes during follow-up.

| Total (n=1078) | Beta-blockers (n=531) | No beta-blockers (n=547) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEIs | 357 (33%) | 184 (35%) | 173 (32%) | 0.301 |

| ARBs | 370 (34%) | 199 (37%) | 171 (31%) | 0.034 |

| ARNIs | 2 (0.19%) | 2 (0.38%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.242 |

| ACE/ARB/ARNI | 716 (66%) | 378 (71%) | 338 (62%) | 0.001 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 192 (18%) | 99 (19%) | 93 (17%) | 0.524 |

| Ivabradine | 30 (2.8%) | 14 (2.6%) | 16 (2.9%) | 0.854 |

| Digoxin | 35 (3.2%) | 15 (2.8%) | 20 (3.7%) | 0.494 |

| Statins | 537 (50%) | 315 (59%) | 222 (41%) | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics | 905 (84%) | 478 (90%) | 427 (78%) | <0.001 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 131 (12%) | 63 (12%) | 68 (12%) | 0.781 |

| 3-month all-cause mortality | 53 (4.9%) | 20 (3.8%) | 33 (6.0%) | 0.092 |

| 3-month HF admissions | 89 (8.3%) | 48 (9.0%) | 41 (7.5%) | 0.377 |

| 3 month all-cause mortality and/or HF admissions | 133 (12%) | 62 (12%) | 71 (13%) | 0.519 |

| 6-month all-cause mortality | 90 (8.3%) | 42 (7.9%) | 48 (8.8%) | 0.660 |

| 6-month HF admissions | 130 (12%) | 72 (14%) | 58 (11%) | 0.160 |

| 6 month all-cause mortality and/or HF admissions | 198 (18%) | 102 (19%) | 96 (18%) | 0.529 |

| One-year all-cause mortality | 161 (15%) | 77 (15%) | 84 (15%) | 0.733 |

| One-year HF admissions | 201 (19%) | 108 (20%) | 93 (17%) | 0.159 |

| One-year all-cause mortality and/or HF admissions.) | 314 (29%) | 162 (31%) | 152 (28%) | 0.348 |

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNIs: angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors; HF: heart failure.

Patients on beta-blocker therapy more often had a prior diagnosis of hypertension, dyslipidemia, or ischemic heart disease. By contrast, they were less often diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or a valve disease-related HF etiology. Patients on beta-blockers were also more independent in the performance of activities of daily living (better Barthel index scores) but also had a higher comorbidity burden (higher Charlson index scores). Likewise, they had a lower heart rate and were more often treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), as well as loop diuretics and statins. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that hypertension (odds ratio [OR] 1.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.09-2.74; p<0.021), ischemic heart disease (OR 2.8, 95% CI 2.06-3.97; p<0.0001), Charlson score (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.03-1.15; 0.004), Barthel score (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.01-1.02; p<0.001), COPD (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.34-0.64; p<0.001), admission heart rate (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98-1.00; p=0.03), discharge use of ACEIs/ARBs/ARNIs (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.01-1.78; p=0.042) and discharge use of loop diuretics (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.66-3.58; p<0.001) were independent predictors of beta-blocker prescription at discharge.

Beta-blockers and adverse clinical eventsPatients who received discharge therapy with beta-blockers did not experience lower mortality rates at one year (or at three or six months) after the index admission. There was also no significant difference in the composite outcome of overall mortality or heart failure admission at three, six or 12 months (Table 2).

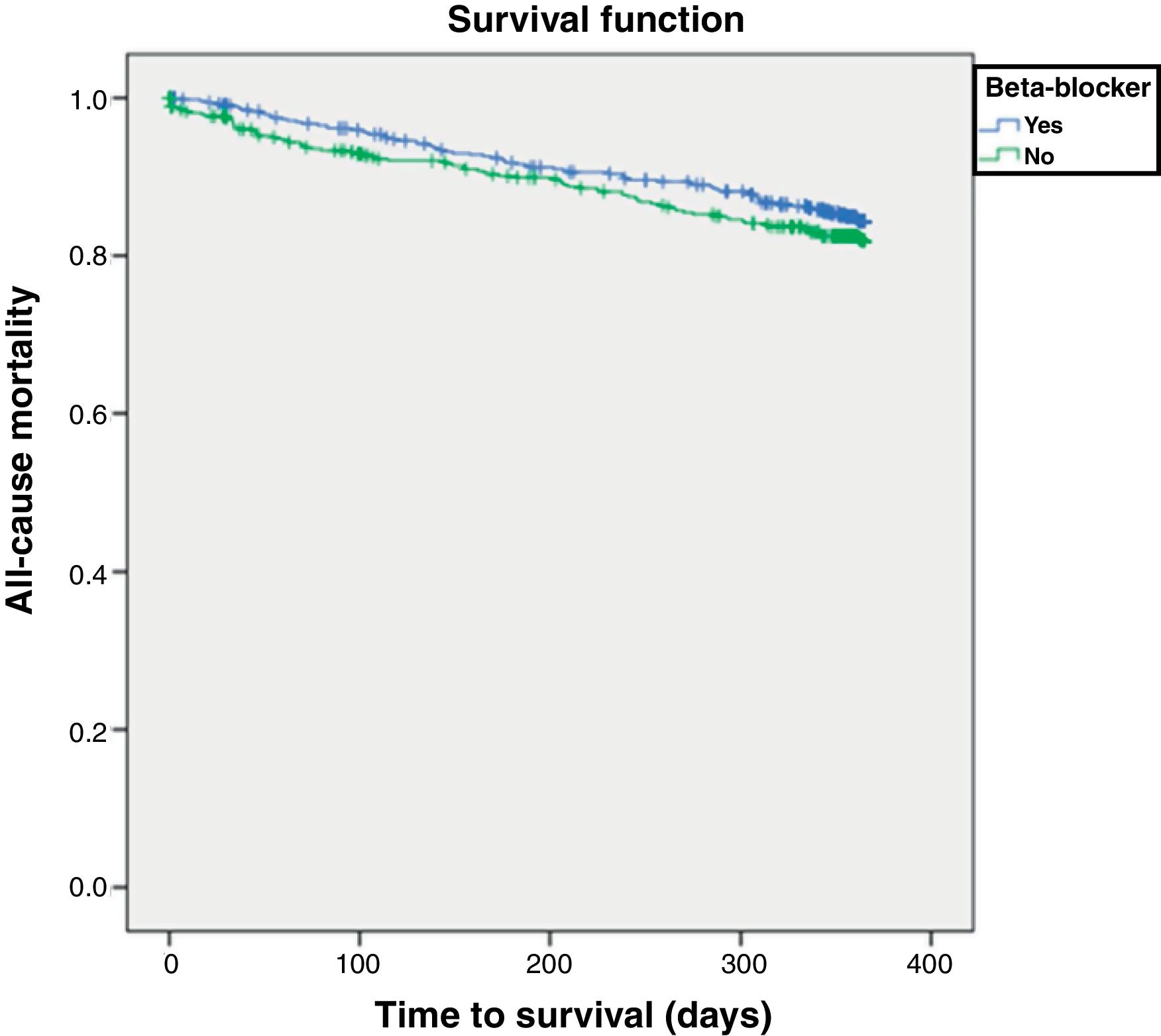

Factors associated with all-cause mortalityA total of 161 patients (15%) died within 12 months of follow-up. Table 3 shows the factors associated with HF-related mortality. After multivariate adjustment, beta-blockers were not associated with total mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.83, 95% CI 0.61-1.13; p=0.236). Covariates associated with mortality were male gender, higher heart rate, valvular disease, higher comorbidity, poor physical performance, poor renal function, and treatment with loop diuretics. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for one-year all-cause mortality according to beta-blocker prescription status (log-rank p=0.235).

Factors associated with one-year all-cause mortality.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | 0.043 | ||

| Male gender | 1.22 (0.89-1.66) | 0.218 | 1.54 (1.10-2.16) | 0.012 |

| Heart rate | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.036 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.022 |

| Hypertension | 1.14 (0.64-2.00) | 0.659 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.03 (0.76-1.40) | 0.850 | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.70 (1.21-2.39) | 0.002 | ||

| SBP | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.063 | ||

| Etiology | ||||

| Ischemic | 1.09 (0.75-1.57) | 0.656 | ||

| Hypertensive | 0.72 (0.52-0.99) | 0.041 | ||

| Valvular | 1.96 (1.36-2.81) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.66-3.48) | <0.001 |

| Institutionalized | 0.99 (0.50-1.94) | 0.974 | ||

| Charlson index | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.01-1.15) | 0.026 |

| Stroke | 1.49 (0.99-2.24) | 0.056 | ||

| COPD | 1.35 (0.96-1.90) | 0.084 | ||

| Barthel index | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | <0.001 |

| Pfeiffer index | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) | <0.001 | ||

| NYHA functional class | ||||

| I-II | 0.66 (0.48-0.90) | 0.010 | ||

| III-IV | 1.52 (1.11-2.10) | 0.010 | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 0.94 (0.87-1.01) | 0.098 | ||

| eGFR, <60 ml/min | 1.73 (1.23-2.42) | 0.002 | 1.68 (1.18-2.41) | 0.004 |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 1.01 (0.97-1.04) | 0.720 | ||

| Potassium, mmol/l | 1.22 (0.98-1.53) | 0.082 | ||

| Treatment at discharge | ||||

| ACEIs and/or ARBs | 0.86 (0.62-1.19) | 0.352 | ||

| Beta-blockers | 0.83 (0.61-1.13) | 0.236 | ||

| Loop diuretics | 0.86 (0.55-1.36) | 0.527 | 0.60 (0.38-0.95) | 0.030 |

| Thiazides | 0.81 (0.49-1.34) | 0.415 | ||

| Aldosterone antagonists | 1.33 (0.92-1.92) | 0.128 | ||

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR MDRD: estimated glomerular filtration rate by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula; HR: hazard ratio; NHYA: New York Heart Association; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

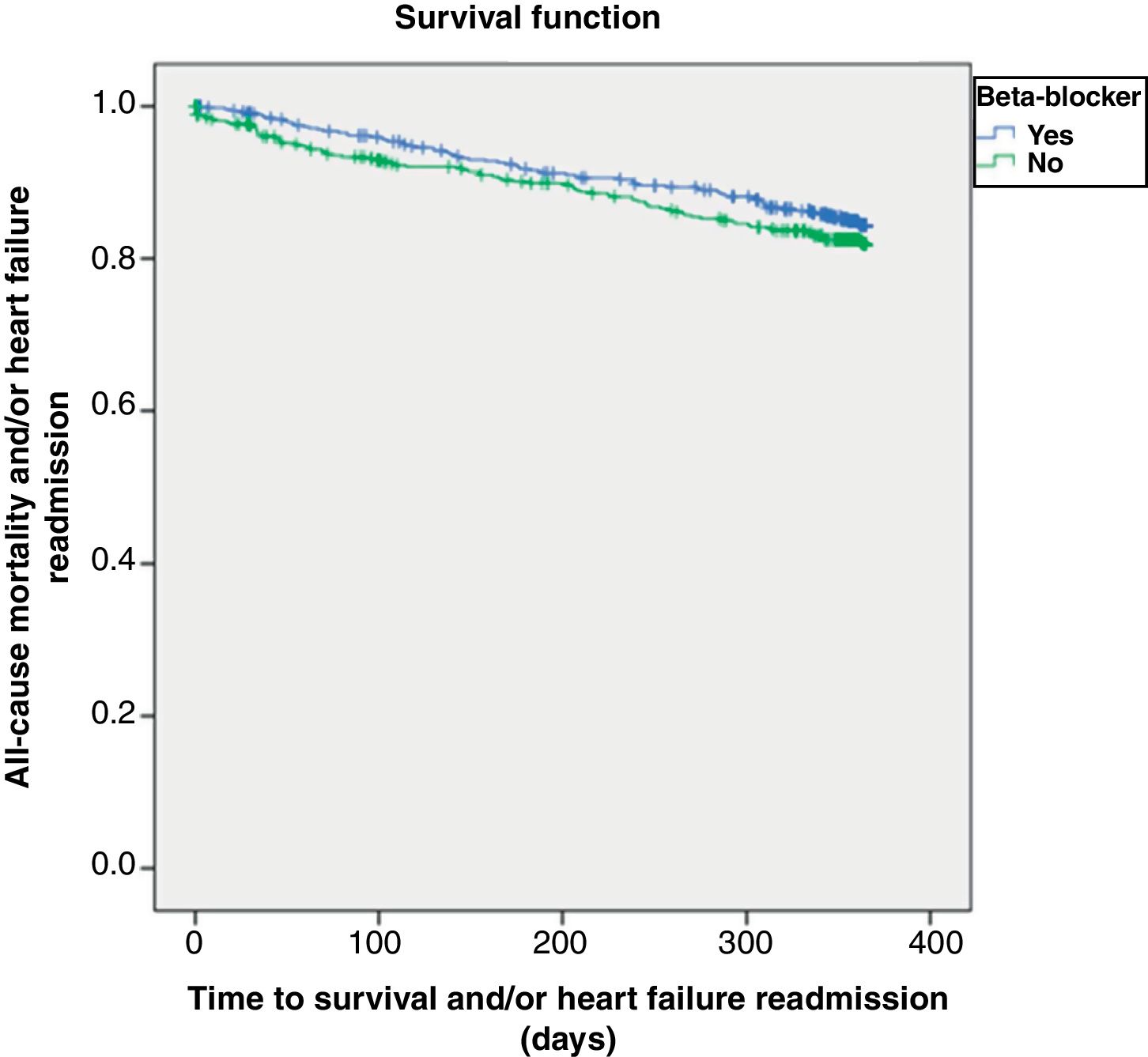

At one year of follow-up, 314 (29%) patients had either died or been readmitted. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for one-year all-cause mortality or HF-related admission according to beta-blocker prescription, which again did not significantly influence these outcomes (log-rank p=0.882).

Table 4 shows the factors associated with one-year all-cause mortality or HF readmission. Multivariate analysis confirmed that beta-blocker therapy was not related to this combined endpoint (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.79-1.23; p=0.882). Instead, a prior history of coronary heart disease, HF due to ischemic or valvular etiology, higher comorbidity burden, past stroke history, poor cognitive status and higher potassium levels were associated with a worse prognosis.

Factors associated with one-year all-cause mortality and/or heart failure readmission.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.096 | ||

| Male gender | 1.02 (0.81-1.28) | 0.864 | ||

| Heart rate | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.644 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.48 (0.95-2.30) | 0.084 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.09 (0.87-1.36) | 0.450 | ||

| Ischemic cardiopathy | 1.72 (1.35-2.18) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.07-1.79) | 0.012 |

| SBP | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.219 | ||

| Etiology | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.096 | ||

| Ischemic | 1.33 (1.03-1.70) | 0.028 | 1.38 (1.04-1.83) | 0.024 |

| Hypertensive | 0.74 (0.59-0.93) | 0.009 | ||

| Valvular | 1.43 (1.08-1.90) | 0.013 | 1.61 (1.17-2.21) | 0.003 |

| Institutionalized | 0.76 (0.45-1.30) | 0.322 | ||

| Charlson index | 1.10 (1.06-1.15) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.62 (1.22-2.16) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.04-1.96) | 0.028 |

| COPD | 1.42 (1.11-1.81) | 0.005 | ||

| Barthel index | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | <0.001 | ||

| Pfeiffer index | 1.09 (1.03-1.15) | 0.002 | 1.06 (1.01-1.13) | 0.027 |

| NYHA functional class | ||||

| I-II | 0.71 (0.56-0.90) | 0.005 | ||

| III-IV | 1.40 (1.11-1.77) | 0.005 | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) | 0.006 | ||

| eGFR, <60 ml/min | 1.53 (1.21-1.94) | <0.001 | ||

| Sodium, mmol/l | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | 0.349 | ||

| Potassium, mmol/l | 1.26 (1.07-1.48) | 0.005 | 1.20 (1.00-1.42) | 0.004 |

| Treatment at discharge | ||||

| ACEIs and/or ARBs | 1.10 (0.87-1.38) | 0.436 | ||

| Beta-blockers | 0.98 (0.79-1.23) | 0.882 | ||

| Thiazides | 0.80 (0.56-1.15) | 0.225 | ||

| Aldosterone antagonists | 1.02 (0.77-1.35) | 0.902 | ||

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NHYA: New York Heart Association; eGFR MDRD: estimated glomerular filtration rate by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

The main result of our study is that nearly half of the elderly HF patients in the RICA cohort with HFpEF in sinus rhythm (20.3% of the total RICA sample) were discharged with a beta-blocker. These patients’ profile was defined by a previous history of hypertension, a higher comorbidity burden (including prior ischemic heart disease), and better functional status, but a lower prevalence of COPD. These patients also had lower heart rate and were more often prescribed with ACEIs/ARBs/ARNIs and loop diuretics. In this cohort, being on beta-blockers did not improve the risks of either all-cause mortality or the combined outcome of all-cause mortality plus HF-related readmission in the short to mid term (one year).

Regarding the use of beta-blockers in patients with HFpEF, in the recent PARAGON trial13 75% of the participants were pre-treated with beta-blockers (32% of the total included patients also had a diagnosis of AF), a percentage similar to the 79% found in the TOPCAT trial (34% again with a concomitant diagnosis of AF)14 and higher than the 59% found in I-PRESERVE (29% AF),15 56% of CHARM-preserved16 (29% AF) and 55% of PEP-CHF17 (21% AF). These latter percentages, of just over half of the study being treated with beta-blockers, are similar to those reported in our RICA registry (53%), in which the percentage of patients receiving beta-blockers in cases of HFpEF was similar (p=0.182) for both the group without (51%) and with AF (55%).8 In the TOPCAT trial, 42.6% of patients receiving beta-blockers had an AF diagnosis.19 These figures, showing that beta-blocker prescription rates are higher than the proportion of patients with HF and AF, confirm that our sample follows the same prescription trend, even though there is no scientific evidence for beta-blocker use in HFpEF.

Regarding prognosis, many previous studies included patients with intermediate ejection fraction (EF) (40-50%), a subset of HF for which beta-blockers might be clinically useful. Lund et al.,19 using data from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry, reported that among HFpEF patients (EF ≥40%), beta-blocker use was associated with lower all-cause mortality (one-year survival 84% vs. 78%) but not with reduction of combined all-cause mortality or heart failure hospitalization. A secondary analysis of the TOPCAT trial reported that for patients with EF ≥50%, beta-blocker use was associated with an increased risk of HF hospitalizations but not of cardiovascular disease mortality, whereas for patients with EF between 45% and 49% no such association was found.18 The SENIORS study was underpowered to analyze the subgroup of patients with EF ≥50%.20

Beta-blockers are frequently prescribed in patients without indications for associated comorbidities (tachyarrhythmias or exertional angina), likely based on extrapolations of pathophysiological pathways that have not been well clarified in HFpEF and may sometimes be paradoxical. Sympathetic antagonism may promote a reduction in myocardial oxygen demand and have anti-ischemic, antiarrhythmic and antiremodeling effects, besides reducing blood pressure and prolonging ventricular filling time, among other possible beneficial mechanisms.21 However, cardiac output in a hypertrophic and rigid myocardium is highly dependent on heart rate, and therefore any slowing might hinder an appropriate increase in output that is needed for exertion.22 Furthermore, slowing heart rate leads to prolongation of diastolic filling, which increases end-systolic volumes and pressures, contributing to significant stress on the myocardial wall.23 Manbiar et al.24 have shown that beta-blocker withdrawal in stable patients with HFpEF was associated with a significant reduction in natriuretic peptides, a marker of myocardial stress.

Current evidence in patients with HFpEF and ischemic heart disease only supports the prescription of beta-blockers in the early phase after an acute coronary syndrome and for the management of angina.9 Data from the TOPCAT study showed that the use of beta-blockers in patients without prior myocardial infarction was associated with poorer health outcomes (increased risk of all-cause death, major cardiovascular events, and hospitalization for HF).18 In our real-world data, however, we did not find this negative association.

New techniques, such as assessment of myocardial global longitudinal strain (GLS), may help select HFpEF patients who could potentially benefit more from beta-blockade. For patients with HF and LVEF ≥40%, beta-blocker use is associated with improved survival in those with GLS <14%.25 Chronotropic incompetence, on the other hand, is very common among the elderly and is associated with a poor maximum functional capacity.26,27

The main strength of our study is that it is based on prospective data from a multicenter, homogeneous real-world elderly HFpEF cohort who have experienced an episode of AHF, a subset of HF patients for whom clinical information derived from clinical trials is almost non-existent. Nevertheless the study has several limitations. First, it is a cohort study, not a randomized trial, and thus may be subject to various selection biases. For instance, patients who die during the index admission are not included in the registry. Second, biomarkers were available for only a subgroup of our patients. Third, other than recording treatment at discharge, we did not analyze how post-discharge management or intervening incidents may have affected mortality or readmission risk. Fourth, the reasons behind the choice (and type) of beta-blocker prescription were not recorded, and neither were data on further up-titration, dose modification or withdrawal. Also, we did not analyze medications used before the index admission, so the possible legacy effect of beta-blocker prescription was not accounted for.

ConclusionIn conclusion, the use of beta-blockers in elderly patients with HFpEF in sinus rhythm does not seem to influence major clinical outcomes (death or HF readmission) within a year following an AHF admission. Whether these results might affect prescription habits in this subset of HF patients remains to be tested in appropriate trials.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We gratefully acknowledge all investigators who form part of the RICA Registry and thank RICA's Registry Coordinating Center, S&H Medical Science Service, and Prof. Salvador Ortiz, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and Statistical Advisor, S&H Medical Science Service, for the statistical analysis.

Álvarez Rocha P, Anarte L, Aramburu-Bodas O, Arévalo-Lorido JC, Arias Jiménez JL, Carrascosa S, Cepeda JM, Cerqueiro JM, Chivite Guillén D, Conde-Martel A, Dávila Ramos MF, Díaz de Castellví S, Epelde F, Formiga Pérez F, García Campos A, González Franco A, León Acuña A, López Castellanos G, Lorente Furió O, Manzano L, Montero-Pérez-Barquero M, Moreno García MC, Ormaechea Gorricho G, Quesada Simón MA, Ruiz Ortega R, Salamanca Bautista MP, Silvera G, Trullàs JC.