Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the result of a complex pathophysiological process with various dynamic factors. The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) is a validated instrument for estimating stress levels in clinical practice and may be useful in the assessment of ACS.

MethodsWe carried out a single-center prospective study engaging patients hospitalized with ACS between March 20, 2019 and March 3, 2020. The PSS-10 was completed during the hospitalization period. The ACS group was compared to a control group (the general Portuguese population), and a subanalysis in the stress group were then performed.

ResultsA total of 171 patients with ACS were included, of whom 36.5% presented ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 38.1% were female and the mean PSS score was 19.5±7.1. Females in the control group scored 16.6±6.3 on the PSS-10 and control males scored 13.4±6.5. The female population with ACS scored 22.8±9.8 on the PSS-10 (p<0.001). Similarly, ACS males scored a mean of 17.4±6.4 (p<0.001). Pathological stress levels were not a predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events or severity at admission.

ConclusionsACS patients had higher perceived stress levels compared to the control group. Perceived stress level was not associated with worse prognosis in ACS patients.

Síndrome coronária aguda (SCA) é resultado de uma complexa relação entre fatores dinâmico-indivíduais e processos fiso-patologicos inerentes a cada indivíduo. A Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) é um instrumento válido e usado habitualmente na prática clínica e pode ser usado na avaliação do stress percecionado em doentes com SCA.

MétodosEstudo prospetivo que incluiu doentes hospitalizados por SCA entre 20/03/2019-31/03/2020. PSS-10 foi realizado durante o internamento por SCA. O grupo de doentes com SCA foi comparado com a população controlo (população portuguesa geral) e posteriormente a subanálise do grupo SCA foi executada.

ResultadosForam incluídos 171 doentes com SCA, 36,5% apresentaram Enfarte Agudo do Miocárdio com Elevação do Segmento ST (EAMCESST), 38,1% eram mulheres com uma pontuação média no PSS-10 de 19,5±7,1. As mulheres na população controlo têm em média 16,6±6,3 pontos na PSS-10, enquanto a população masculina controlo tem 13,4±6,5 pontos. As mulheres no grupo com SCA apresentaram 22,8±9,8 pontos na PSS-10 (p<0,001). Por sua vez, o género masculino com SCA apresentou 17,4±6,4 pontos na PSS-10, p<0,001. Níveis patológicos de stress percecionado não foram preditores de eventos cardiovasculares major nem de gravidade na admissão.

ConclusõesOs doentes com SCA apresentaram maiores índices de stress percecionado comparando com a população controlo. Maiores níveis de stress percecionado não foram associados a pior prognóstico em doentes com SCA.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a prevalent disease in the general population secondary to plaque disruption that results from a complex pathophysiological interaction between endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic factors and inflammatory modulators. Multiple factors influence the manifestations of ACS, and multiple variables influence coronary vascular dysfunction, atherosclerotic plaque rupture and the thrombotic cascade.1 Stress is a common problem reported in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and can be an independent trigger for cardiovascular events like ACS and sudden cardiac death.2

The association between ACS and stress has frequently been documented and some authors argue that stress can be a critical risk factor for ACS and a prognostic marker.3 The physiological mechanism that underlies the relationship between stress, plaque rupture and thrombus formation is not completely clarified, nonetheless, it has been suggested that stress may cause various abnormalities in platelet activation and endothelial function.4

Stress is a difficult concept to characterize since it is a global systemic response to internal and external stimuli. There has been extensive research into stress and its implication for human health. However, individual responses to stressful situations make it difficult to determine and categorize levels of stress and their significance for health consequences. Many techniques and instruments have been tested to identify and quantify stress levels.5

Perceived stress is a more realistic measure than objective stress levels, and is therefore a better health predictor. Stress stimuli are not sufficient to provoke a pathological manifestation; it is the interaction between the individual and their environment, as well their assessment of the event and their personal reaction to it, that will determine perceived stress.

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) is one of the most widely used instruments to estimate stress in clinical practice and has been validated in the Portuguese population.5 This score helps to show how life events are perceived, considering the individual response to daily events, interpersonal relationships and personal perspectives. In view of the low predictive value of perceived stress, the scale has been validated only for the month previous to the event.5

The PSS-10 has been applied in the Portuguese population, particularly in subgroups with CAD. Nonetheless, the association of perceived stress level and ACS is still controversial and has not been investigated in the Portuguese population. We tested the association of perceived stress and ACS occurrence among the Portuguese population.

ObjectiveWe aimed to assess perceived stress levels in patients admitted for ACS.

MethodsWe carried out a single-center prospective study engaging patients hospitalized with ACS between March 20, 2019 and March 3, 2020. All ACS patients older than 18 years were eligible for inclusion. ACS episodes were adjudicated according to current guidelines based on electrocardiogram, myocardial necrosis biomarkers and clinical status.7 Data collected included patient demographics and baseline characteristics, presenting symptoms, biochemical, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings, clinical course, medical treatment (background, in-hospital and post-discharge), coronary anatomy, revascularization procedures, and clinical outcomes. All participants completed the PSS-10 during their hospitalization for ACS.

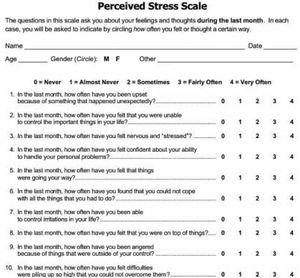

The Portuguese version of the PSS-10 was validated in the Portuguese population by Trigo et al.5 It consists of 10 questions with five possible answers (Figure 1), in which each question is scored between 0 and 4, for a maximum of 40 (0 – never, 1 – almost never, 2 – sometimes, 3 – fairly often, 4 – very often), in order to assess stress levels in the context of physical disease. When calculating the final score, since questions 4, 5, 7 and 8 reflect positive situations, the scores for these questions are reversed. The pathological stress level established in the Portuguese population was >20 in males and >22 in females.

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale by Cohen et al.6 on which the questionnaire used in the present article was based.

A total of 231 validated episodes were recorded, but only 171 patients completed the PSS-10. Patients with missing data regarding the ACS or incomplete or inadequate PSS-10 questionnaires were excluded. Patients who presented an ACS during this period were denominated the stress group, while the Portuguese general population, as described by Trigo et al.,5 were taken as the control group.

Frailty was defined as the presence of at least five of the following comorbidities, as previously described8: smoking, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, ischemic cardiomyopathy, valve disease, stroke, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, peripheral arterial disease, dementia, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) during hospitalization were defined as reinfarction, congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock, mechanical complications, atrioventricular block, sustained ventricular tachycardia, aborted cardiac arrest, new-onset atrial fibrillation, stroke and major bleeding.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 20.0 for Windows XP. Continuous variables are described as mean and standard deviation if normally distributed, or median and interquartile range in cases of skewed distribution. Categorical variables are described as absolute and relative frequencies. The Student's t test was used to compare categorical and continuous variables between groups and/or the Portuguese population. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to establish the relationship between variables and stress levels.

The study was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of Centro Hospitalar Barreiro-Montijo. It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the confidentiality and anonymity of all patient information was ensured. Written informed consent was obtained for all the participants.

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationA total of 171 patients with ACS completed the PSS-10, of whom 36.5% presented ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and 38.1% were female. Mean age was 64.54±12.61 years and mean PSS score was 19.47±7.08. This result is significantly different from the expected perceived stress in the control group (15.3±6.6) (p<0.001). The complete population characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Regarding ACS presentation, the mean PSS-10 score in STEMI patients was 18.54±8.49 compared to 20.55±6.15 in non-STEMI patients, and the difference between these groups was significant (p=0.014).

Patients with a previous history of CAD, independently of their current ACS hospitalization, scored 23.80±5.84 on the PSS-10, while those without a previous history scored 20.89±6.33, with no significant differences between these two groups.

Smoking status in the control group was associated with higher levels of perceived stress, nonetheless, no differences were detected compared to the ACS group (p=0.236). Also, comparison of smoking status in the ACS group showed no significant difference (Table 1).

Population characteristics according to smoking status.

| Non-smokers | Smokers | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSS-10 score | 19.2±7.5 | 19.6±6.5 | 0.700 |

| Weight, kg | 75.3±12.2 | 76.0±13.3 | 0.828 |

| Female, % | 37.9 | 33.9 | 0.625 |

| STEMI, % | 36.0 | 35.3 | 0.929 |

| Age, years | 66.8±12.2 | 60.2±12.7 | 0.003 |

| Hypertension, % | 63.2 | 80.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 43.2 | 41.1 | 0.271 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 69.5 | 89.3 | 0.061 |

| Previous ACS, % | 30.5 | 10.7 | 0.005 |

| Previous stroke, % | 3.2 | 5.4 | 0.504 |

| PAD, % | 5.3 | 1.8 | 0.413 |

| CKD, % | 4.2 | 3.6 | 0.846 |

| Cancer, % | 2.1 | 5.4 | 0.360 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 79.9±21.0 | 81.7±20.8 | 0.617 |

| SBP, mmHg | 148.2±30.7 | 141.0±33.8 | 0.182 |

| Killip class I, % | 45.7 | 40.6 | 0.284 |

| Normal coronary angiography, % | 27.0 | 21.8 | 0.749 |

| Preserved LVEF, % | 27.4 | 30.4 | 0.747 |

| Reinfarction, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Heart failure, % | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.606 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation, % | 5.3 | 0 | 0.095 |

| Mechanical complication, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Complete AV block, % | 1.1 | 0 | 0.629 |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia, % | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.606 |

| Cardiac arrest, % | 1.1 | 3.6 | 0.309 |

| Stroke, % | 2.1 | 0 | 0.394 |

| Major bleeding events, % | 0 | 1.8 | 0.371 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 7.8±6.2 | 8.6±8.1 | 0.511 |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AV: atrioventricular; CKD: chronic kidney disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; PSS-10: 10-item Perceived Stress Scale; SBP: systolic blood pressure; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

According to Trigo et al.,5 the mean PSS score for Portuguese females is 16.6±6.3. Female patients in the stress group scored 22.85±6.3 on the PSS-10 in the month previous to ACS (Table 2), showing significantly higher stress levels in this population compared with the expected stress level. Furthermore, the female control group with a history of CAD, according to Trigo et al.,5 scored 20.8±9.8. In our population, only 20% of female patients had a history of CAD, and they had similar stress levels to the same population in the control group. Also, no differences in stress levels in our female population were detected regarding the presence or absence of CAD.

Population characteristics and previous medication according to gender.

| Female | Male | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSS-10 score | 22.9±6.9 | 17.4±6.4 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 71.1±11.7 | 78.3±13.7 | <0.001 |

| Height, m | 161.9±7.2 | 169.4±7.2 | 0.078 |

| STEMI, % | 36.4 | 36.6 | 0.981 |

| Age, years | 66.6±11.6 | 63.0±13.1 | 0.078 |

| Smoking, % | 34.5 | 38.5 | 0.625 |

| Hypertension, % | 56.4 | 73.2 | 0.034 |

| Diabetes, % | 30.9 | 30.9 | 0.998 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 49.1 | 51.5 | 0.711 |

| Previous ACS, % | 20.0 | 24.7 | 0.505 |

| Valve disease, % | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.682 |

| Previous heart failure, % | 0 | 3.1 | 0.188 |

| Previous stroke, % | 3.6 | 4.1 | 0.882 |

| PAD, % | 3.6 | 4.1 | 0.882 |

| CKD, % | 5.5 | 3.1 | 0.472 |

| Cancer, % | 1.8 | 4.1 | 0.450 |

| COPD, % | 0 | 2.1 | 0.444 |

| Dementia, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Frailty, % | 12.7 | 23.7 | 0.102 |

| Aspirin, % | 20.8 | 34.7 | 0.074 |

| Clopidogrel, % | 7.4 | 9.5 | 0.667 |

| Ticagrelor, % | 0 | 3.2 | 0.187 |

| VKA, % | 1.9 | 0 | 0.283 |

| NOAC, % | 3.7 | 3.2 | 0.183 |

| Beta-blocker, % | 18.9 | 25.3 | 0.375 |

| ACEI/ARB, % | 45.3 | 50.5 | 0.777 |

| Statin, % | 26.4 | 42.1 | 0.057 |

| Nitrates, % | 7.4 | 12.6 | 0.322 |

| CCB, % | 18.9 | 14.7 | 0.513 |

| Ivabradine, % | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.916 |

| MRA, % | 1.9 | 3.2 | 0.635 |

| Diuretic, % | 28.3 | 26.3 | 0.794 |

| Amiodrarone, % | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.916 |

| Insulin, % | 5.6 | 7.4 | 0.671 |

| Oral antidiabetic drug, % | 13.0 | 21.1 | 0.218 |

ACEI/ARB: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptors blocker; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CCB: calcium channel blocker; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NOAC: novel oral anticoagulant; PSS-10: 10-item Perceived Stress Scale; VKA: vitamin K antagonist.

The mean PSS-10 score in males in the control group was 13.4±6.5, and in males with a previous history of CAD it was 13.4±7.9. In our population, male patients with ACS had a mean score of 17.37±6.37, with a significant difference compared to the male control group. Our male population with previous CAD presented a significant difference in stress levels (18.2±6.8) compared to the control male group with previous CAD (p<0.001).

No differences between the sexes were found regarding age, prevalence of cardiovascular conditions and other comorbidities (smoking status, diabetes, dyslipidemia, history of CAD, and previous heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, previous stroke and frailty), STEMI, clinical data at admission, Killip class at admission, blood work, previous therapy or therapy during hospitalization. Male patients had a high prevalence of hypertension (Table 2).

Females presented a higher percentage of MACE during hospitalization, although without statistical significance except for new-onset atrial fibrillation, which was more frequent in females (7.30% vs. 1.00%, p=0.038) (Table 3).

Clinical management, angiographic findings and in-hospital adverse events according to gender.

| Female | Male | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial access, % | 96.1 | 93.2 | 0.480 |

| Normal coronary angiography, % | 32.1 | 20.7 | 0.208 |

| Preserved LVEF, % | 80.0 | 67.10 | 0.052 |

| Reinfarction, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Heart failure, % | 0 | 2.1 | 0.284 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation, % | 7.3 | 1.0 | 0.038 |

| Mechanical complication, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Complete AV block, % | 0 | 1.0 | 0.450 |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia, % | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.682 |

| Cardiac arrest, % | 1.8 | 3.1 | 0.637 |

| Stroke, % | 3.6 | 0 | 0.059 |

| Major bleeding events, % | 0 | 1.0 | 0.450 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 7.6±7.2 | 8.5±6.8 | 0.432 |

AV: atrioventricular; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

Seventy patients presented stress levels considered pathological in the Portuguese population according to Trigo et al.5 (>20 in males and >22 in females on the PSS-10). Patients presenting with pathological stress had lower weight (73.52±12.32 kg vs. 77.09±14.13 kg, p=0.035) and a lower rate of normal coronary angiography (24.71% vs. 29.41%, p=0.050). No differences between groups were detected regarding age, gender, STEMI presentation, cardiovascular conditions and other comorbidities, clinical vital signs at admission, blood analysis parameters at admission, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), MACE or hospital length of stay (Table 4). None of the variables was a predictor of pathological stress in the month prior to ACS.

Population characteristics according to pathological or non-pathological stress.

| Pathological stress | Non-pathological stress | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSS-10 score | 26.2±3.6 | 14.4±4.2 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 73.5±12.3 | 77.1±14.1 | 0.035 |

| Female gender, % | 23.5 | 11.8 | 0.167 |

| STEMI, % | 25.9 | 29.4 | 0.110 |

| Age, years | 65.9±11.3 | 63.5±13.5 | 0.244 |

| Smoking, % | 14.1 | 18.8 | 0.928 |

| Hypertension, % | 25.3 | 34.7 | 0.829 |

| Diabetes, % | 14.1 | 13.5 | 0.116 |

| Diabetes, % | 20.6 | 24.7 | 0.497 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 9.4 | 11.2 | 0.497 |

| Previous ACS, % | 0.6 | 2.9 | 0.187 |

| PAD, % | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.989 |

| CKD, % | 1.2 | 2.3 | 0.634 |

| Cancer, % | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.295 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 78.7±21.4 | 82.5±21.0 | 0.274 |

| SBP, mmHg | 146.5±30.2 | 145.0±33.2 | 0.775 |

| Killip class I, % | 35.9 | 45.9 | 0.811 |

| Normal coronary angiography, % | 24.7 | 29.4 | 0.050 |

| Preserved LVEF, % | 30.0 | 34.1 | 0.213 |

| Reinfarction, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Heart failure, % | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.971 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation, % | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.652 |

| Mechanical complication, % | 0 | 0 | – |

| Complete AV block, % | 0 | 0.6 | 0.572 |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia, % | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.971 |

| Cardiac arrest, % | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.971 |

| Stroke, % | 1.2 | 0 | 0.181 |

| Major bleeding events, % | 0 | 0.6 | 0.572 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 7.6±6.5 | 8.6±7.3 | 0.407 |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AV: atrioventricular; CKD: chronic kidney disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; PSS-10: 10-item Perceived Stress Scale; SBP: systolic blood pressure; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Frail patients presented high levels of stress on the PSS-10 questionnaire (19.58±7.08 vs. 18.63±7.35), but without significant difference compared to non-frail patients. As expected, frail patients presented a higher prevalence of cardiovascular conditions (smoking, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, previous ACS and previous stroke). Blood glucose levels at admission were lower in frail patients (140.91±69.99 mg/dl vs. 174.82±88.51 mg/dl, p=0.035). Frail patients more frequently presented preserved LVEF (52.35% vs. 11.76%, p<0.001). The occurrence of MACE and hospital length of stay were not significantly different between frail and non-frail patients. Also, frailty was not related to stress levels on the PSS-10.

PrognosisAll patients who completed the PSS-10 were discharged and no deaths were recorded in our population during hospitalization. The presence of higher stress levels on the PSS-10 was not associated with severity at admission, including with Killip class at admission, and were also not predictors of MACE.

DiscussionIn this cohort study, high levels of perceived stress in the month before ACS appeared to influence ACS presentation and manifestations. Our data suggest that patients presenting with ACS had higher levels of perceived stress compared to the general Portuguese population, which demonstrates that stress levels can be considered a direct and indirect risk factor for ACS. To our knowledge, this study is the first in Portugal to examine the association between perceived stress and ACS. In line with our findings, several groups9–11 have shown a relationship between perceived stress and cardiac events, particularly ACS.

Our population had a significant prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, as well as other comorbidities, which is in line with similar reviews on ACS that found a direct relationship between stress and cardiovascular disease.9,12 Considering that the intensity of an event can be perceived by two individuals as leading to different stress levels,13 stress can contribute to various clinical manifestations in different patients. This suggests that in patients with a higher risk of developing an ACS, higher perceived stress may be a trigger for the cardiovascular event.

Stress can influence the natural cardiac rhythm and is a known factor promoting atherosclerosis, leading to CAD.14 These specific pathophysiological responses to stressful situations, including higher concentrations of norepinephrine and neurotransmitters, are associated with increased susceptibility to ACS and, in consequence, to a higher risk of coronary artery occlusion,15 which is consistent with the higher incidence of STEMI in our population. Another indicator of the influence of stress levels on the development of ACS is that reducing inappropriate responses to stressful situations seems to have a beneficial impact on cardiovascular health.13 Nonetheless, Richardson et al.9 argue that stress cannot be directly associated with CAD, unlike other diseases, because no direct association has been found between the two variables, since their interaction probably depends on multiple factors.

Our results revealed a high percentage of patients with pathological stress in the ACS group, a finding that supports the potential influence of stress as a trigger for ACS. However, it seems that pathological stress is not a predictor of MACE, and definitely should not be considered as an isolated variable in ACS, since it did not confer a worse prognosis for these patients. Another curious finding was that patients with pathological stress less frequently had a normal coronary angiogram. This finding may be explained by the direct pathophysiological response to stressful situations, such as tachycardia and hormonal releases that can lead to vasospasm or stress cardiomyopathy.

In our population with ACS, perceived stress levels were higher than in the general population, irrespective of gender. Our study is in agreement with Trigo et al.’s findings regarding females with a history of CAD, since this subgroup of patients in our population had similar stress levels to those of the Portuguese population with a history of CAD and was comparable to the expected stress level of the control group.5 Nonetheless, our female patients with a history of CAD had similar perceived stress levels to those of females without a history of CAD, suggesting that the presence of higher stress levels did not influence the recurrence of ACS.

Regarding the role of gender in perceived stress, in our study males had lower stress levels. This is in agreement with both Trigo et al.’s study of the Portuguese population5 and an American study.16 This finding may be explained by the fact that women are more likely to report physical and mental symptoms than men and have more susceptibility to stress.17 No differences between genders were found in cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, suggesting that the presence of these factors had no impact on perceived stress levels. Nonetheless, our female population presented lower rates of cardiovascular risk factors compared to other ACS series and were older than our male group. Our females were younger than females in those series, which may explain this finding.

No differences were found between the sexes regarding MACE. However, if each event is analyzed separately, new-onset atrial fibrillation was more frequent in women. This is curious, since males have a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation at all ages.18 The fact that our patients were younger and had lower prevalences of cardiovascular risk factors would suggest that no differences in the occurrence of new-onset atrial fibrillation should be expected, and it was not correlated with worse prognosis.

Regarding frail patients, our results diverged from previous studies,19–21 since this population did not show higher stress levels than patients with fewer comorbidities. Interestingly, we found no differences in MACE between frail and non-frail patients, which was unexpected, since other authors found a higher rate of MACE in frail patients.22 This finding may be explained by the small number of participants. Furthermore, we had to exclude some patients who were unable to complete the PSS-10, and these were probably older and frailer.

As pointed out above, higher stress levels can lead to a higher risk of coronary artery occlusion,9,11 however our study found no difference in the occurrence of STEMI between patients with and without pathological stress. Thus the hypothesis of perceived stress as a predictor of STEMI was not confirmed, nor of the potential impact of stress levels on CAD and its manifestations. Previous series reported that MACE rates were directly associated with stress levels,9,16,23 which contradicts our results. The small population included in this analysis may have influenced the observed occurrence of MACE in patients with ACS and stress.

LimitationsThere are several limitations to be considered when interpreting our analysis. This was an observational and non-randomized study, which may have involved confounders that could have influenced the outcomes. Some of the patients could have had misclassified characteristics or incomplete records. Our control population were significantly younger and had fewer comorbidities, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Analysis of differences between patients with and without ACS was performed with univariate, non-adjusted models without correction by multiple inferential tests. Other complications, including non-cardiovascular complications, could have influenced patients’ prognosis but were not considered. Perceived stress was assessed using the PSS-10 during hospitalization for ACS, however, it is uncertain whether ACS can influence assessment of stress levels in the previous month. Since multiple psychosocial features can affect various diseases, it is difficult to establish a direct and isolated relationship between perceived stress levels and outcomes in ACS patients. In view of the small sample of patients, further research with a prospective study is needed to obtain a definitive conclusion on stress levels in ACS patients in Portugal.

ConclusionOur results are in agreement with several publications suggesting that perceived stress levels are a major feature to consider in ACS patients, with an important clinical impact. In the month prior to the event, ACS patients presented higher levels of stress compared with the general population. Women presented a higher level of perceived stress compared to men. Further investigation should focus on the impact that perceived stress has on ACS.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank all medical personnel in Centro Hospitalar Barreiro-Montijo for their contributions to this manuscript.