Atrial septal defect (ASD) is one of the most common congenital cardiac anomalies presenting in adulthood. ASD is characterized by a defect in the interatrial septum that allows pulmonary venous return from the left atrium to pass directly to the right atrium. The magnitude of the left-to-right shunt across the ASD depends on the defect size, the relative compliance of the ventricles, and the relative resistance of both the pulmonary and the systemic circulation.

The three major types of atrial septal defect (ostium secundum, ostium primum and sinus venosus) account for 10% of all congenital heart defects and as much as 20-40% of congenital heart disease presenting in adulthood.

In general, elective closure is recommended for all ASDs with evidence of right ventricular (RV) overload or with a clinically significant shunt (pulmonary flow [Qp] to systemic flow [Qs] ratio >1.5). Lack of symptoms is not a contraindication for repair.1 At any age, ASD closure is followed by symptomatic improvement and regression of RV size.2

Ostium secundum ASD may be closed with a variety of catheter-implanted occlusion devices rather than by direct surgical closure with cardiopulmonary bypass.3 Compared with surgery, transcatheter closure appears to have additional benefits, including hemodynamic improvement and preservation of atrial function.4

Although myocardial mechanics has been primarily used to study left ventricular (LV) performance, since 2007 it has also been applied to the assessment of thin-walled structures such as the left atrium.5 Subsequently, analysis of right atrial (RA) mechanics using two-dimensional (2D) speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) also proved feasible,6–12 and normal reference values have been published.13,14

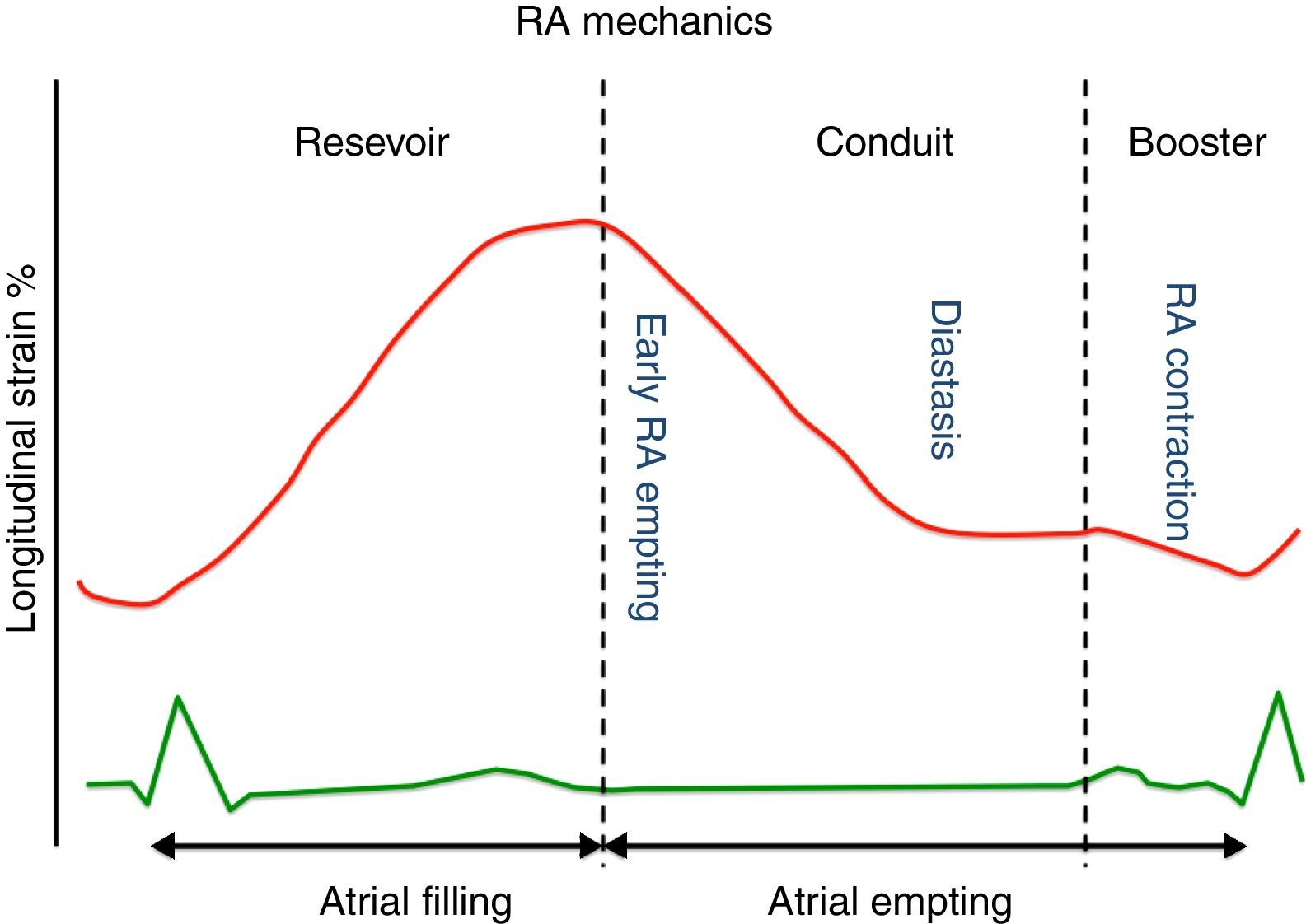

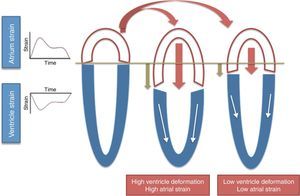

Throughout the phases of the cardiac cycle, the right atrium serves three distinct functions (Figure 1):

- •

Reservoir phase: storage of blood arriving from the systemic venous circuit during ventricular systole;

- •

Conduit phase: passive filling of blood from the inferior and superior venae cavae to the right ventricle during early and mid diastole;

- •

Booster pump phase: contributing to RV filling in late diastole by atrial contraction.

The reservoir and conduit phases are often termed passive phases, whereas the atrial contraction phase is considered the active phase. All phases are modulated by loading conditions, heart rate and the intrinsic contractility of the atria.15

Right atrial peak strain derived from 2D-STE has been proved to be a reliable tool to study RA performance.16 Peak atrial strain (the peak of the positive deflection occurring during the reservoir phase, when the right ventricle contracts and the right atrium fills against a closed tricuspid valve) is perhaps the most used parameter of RA function. It depends on:

- •

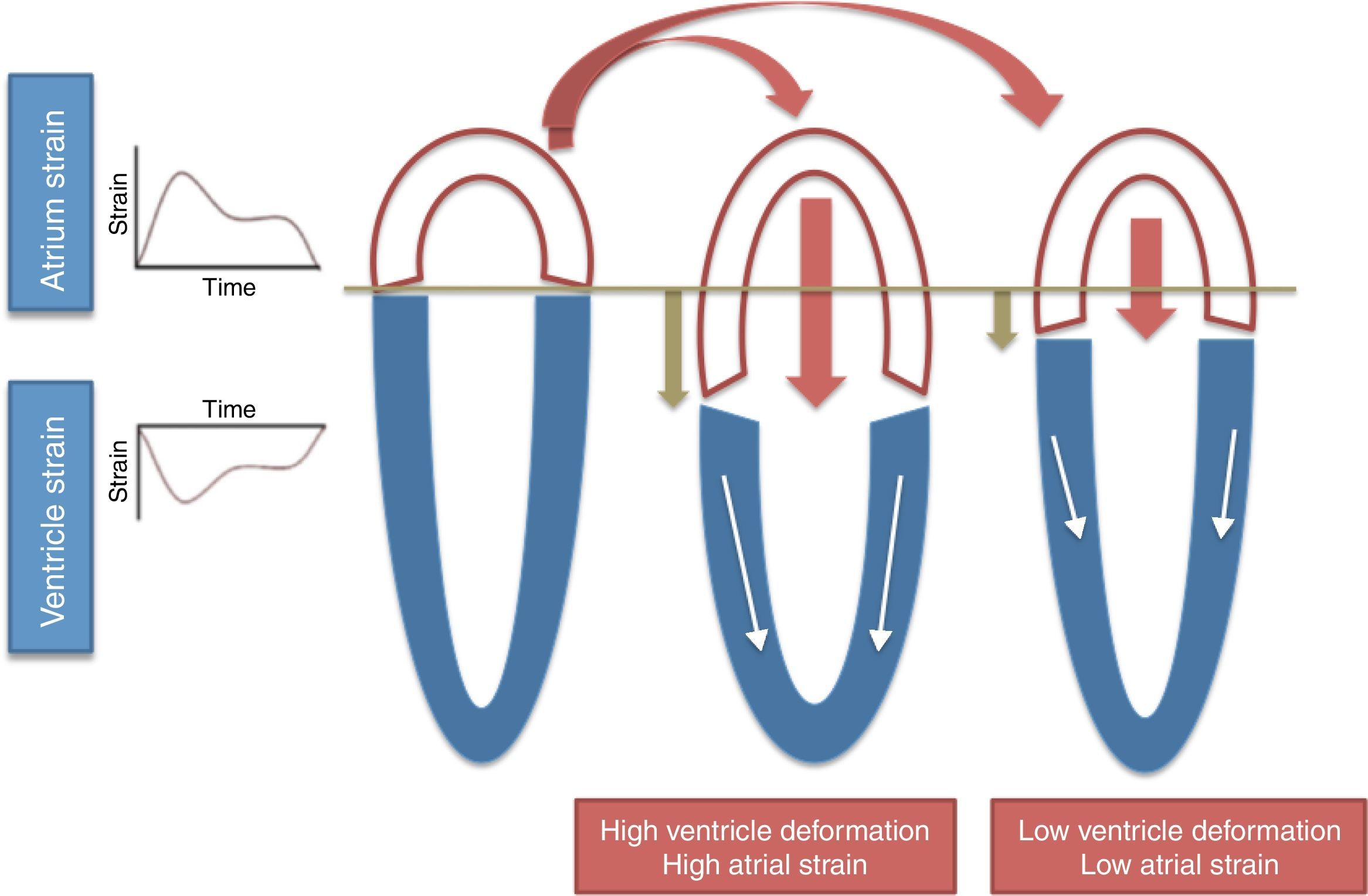

Long-axis ventricular contraction17 – higher longitudinal RV strain results in greater tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) during systole and therefore higher RA strain (Figure 2);

- •

RA compliance17 – less compliant atria have lower strain;

- •

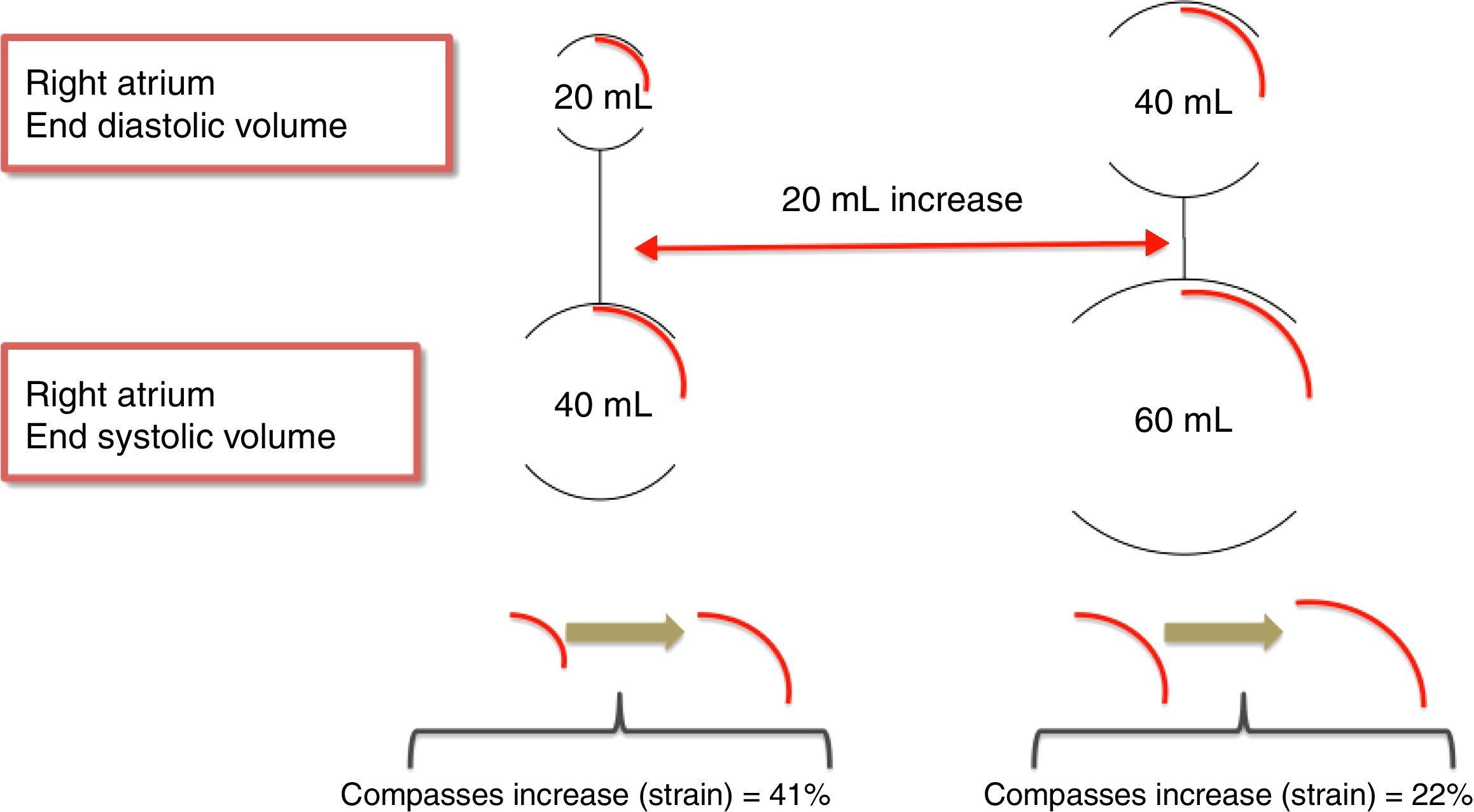

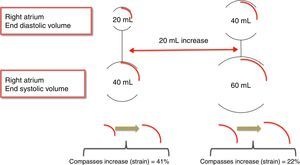

RA volume18 – for the same amount of blood received, dilated atria have lower peak atrial strain than non-dilated atria (Figure 3).

In accordance with the above, since a chronic significant left-to-right shunt through an ASD leads to a varying degree of RA dilatation due to volume overload, peak atrial strain should be decreased in ASD patients, who have dilated atria. However, in the absence of pulmonary hypertension, it should be increased, due to high TAPSE in the presence of increased preload.

In this issue of the Journal, Ozturk et al.19 show that 2D-STE-derived RA peak strain is decreased in ASD patients and increases after ASD closure – a similar result to those of another group20 who used a different methodology (strain derived from tissue Doppler imaging) to demonstrate low peak RA strain before ASD closure.

As pointed out above, RA strain partially depends on RV systolic function and on TAPSE; so as expected, in the study by Ozturk et al.,19 as TAPSE was low, RA peak strain was also low before closure, and both increased after the procedure.

Why was TAPSE decreased before ASD closure, in the presence of a significant ASD with volume overload? The answer probably lies in the high pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) found in Ozturk et al.’s study19 (mean PASP 51.4±16.3 mmHg), which decreases RV systolic performance (as shown by TAPSE) and consequently RA peak strain. In fact, in a previous study by Jategaonkar et al.,21 also with ASD patients but without pulmonary hypertension (mean PASP 19.9±5.2 mmHg), both TAPSE and RV strain decreased after ASD closure.

To conclude, do we really need peak RA strain, it is methodologically complex and difficult to interpretation, when there are simpler and more reproducible measures such as TAPSE (or RV strain)? And do we really need to study the atria with 2D-STE, a cutting-edge technique with great potential in different clinical scenarios, but posing demanding technical challenges for RA assessment (thin walls, difficulty in contouring, many structures fitted into a tight compartment, unusual chamber geometry and poor definition due to its anterior position, and lack of commercially available software specific to the right atrium)?

Let the future clarify our souls.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.