Pulse pressure (PP) is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP). PP rises markedly after the fifth decade of life. High PP is a risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease and heart failure. The aim of this study was to assess whether PP can be used as a prognostic marker in advanced heart failure.

MethodsWe retrospectively studied patients in NYHA class III–IV who were hospitalized in a single heart failure unit between January 2003 and August 2012. Demographic characteristics, laboratory tests, and cardiovascular risk factors were recorded. PP was calculated as the difference between systolic and diastolic BP at admission, and the patients were divided into two groups (group 1: PP >40 mmHg and group 2: PP ≤40 mmHg). Median follow-up was 666±50 days for the occurrence of cardiovascular death and heart transplantation.

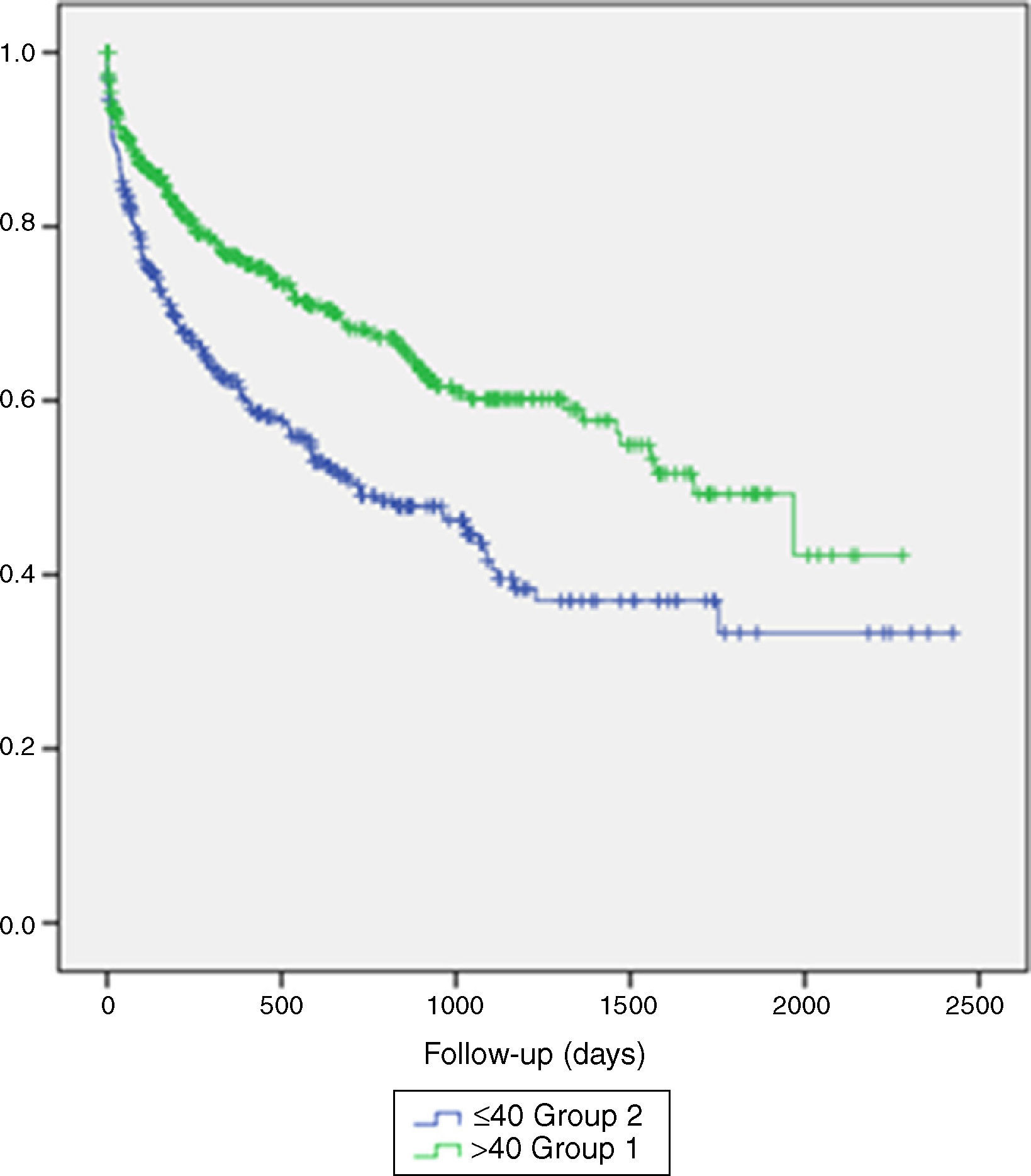

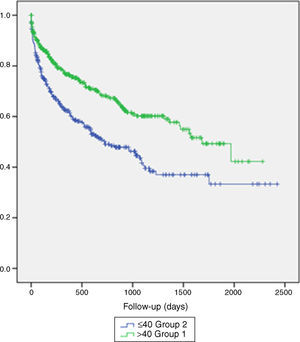

ResultsDuring follow-up 914 patients in NYHA class III–IV were hospitalized, 520 in group 1 and 394 in group 2. The most important difference between the groups was in left ventricular dysfunction, which was greater in patients with lower PP. On Kaplan-Meier analysis, group 2 had higher mortality (38 vs. 24 patients, log-rank p=0.002).

ConclusionsPP is easily calculated, and enables prediction of cardiovascular death in patients with advanced heart failure.

A pressão de pulso (PP) é a diferença entre os valores da pressão arterial sistólica e diastólica (BP). A PP sobe acentuadamente após a quinta década de vida, sendo considerada um fator de risco para o desenvolvimento de doenças cardiovasculares. O objetivo do estudo foi avaliar se a PP pode ser usada como um marcador de prognóstico em doentes com insuficiência cardíaca avançada.

MétodosForam estudados, retrospetivamente, 914 doentes em classe III-IV de NYHA, que foram internados numa unidade de insuficiência cardíaca, entre janeiro de 2003 e agosto de 2012. Foram recolhidos: características demográficas, análises laboratoriais e fatores de risco cardiovascular dos doentes incluídos. A PP foi calculada como a diferença entre a BP na admissão e os doentes foram divididos em dois grupos (PP > 40 mmHg e PP = 40 mmHg). O tempo médio de follow-up foi de 666 ± 50 dias. Os endpoints considerados foram a morte por causa cardiovascular e o transplante cardíaco.

ResultadosDurante o follow-up foram internados 914 doentes, sendo divididos em dois grupos: grupo I: PP > 40 mmHg (520 pacientes); grupo II: PP = 40 mmHg (394 pacientes). A diferença mais importante entre os grupos foi a depressão da função ventricular esquerda mais acentuada no grupo de doentes com PP menor. Na análise KaplanMeyer, o grupo II (PP = 40 mmHg) apresentou maior mortalidade (38 pacientes versus 24 pacientes, log-rank P = 0,002).

ConclusõesA PP é um parâmetro facilmente calculado que se correlaciona com o prognóstico dos doentes com insuficiência cardíaca avançada.

Pulse pressure (PP) is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) and is dependent on stroke volume and arterial wall elastic properties.1

In a young healthy person, each stroke volume received into the central vessels is accommodated by a stretching of these vessels in systole followed by subsequent elastic recoil in late systole and diastole. This is known as arterial compliance and has the effect of maintaining central and peripheral BP within a relatively narrow range. With aging, there is a disruption and fragmentation of the elastic lamellae of the central arteries, as well as alteration of the collagen-to-elastin ratio, leading to arterial stiffness, loss of compliance, and increased pulse wave velocity and therefore increased PP.2

An elevated PP consistently predicts increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, including for coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure (HF) and CV mortality.3,4

The prognostic value of PP in patients with chronic HF is less clear. The SOLVD investigators found that a high PP predicted adverse outcome, especially in patients in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or III.5 In contrast, in patients hospitalized with acute HF, low PP appeared to be an independent predictor of mortality. A low PP (≤40 mmHg) may represent a decrease in cardiac output and reflect a reduction of stroke volume due to left ventricular dysfunction.

The aim of this study was to assess whether PP can be used as a prognostic marker in advanced HF (NYHA class III or IV).

MethodsWe retrospectively studied 914 patients in NYHA class III–IV hospitalized in a single advanced HF unit between January 2003 and August 2012.

Detailed histories of the patients including demographic characteristics, CV risk factors and medication were recorded.

Serum lipid, glucose, creatinine, sodium, potassium, and brain natriuretic peptide levels were measured by routine laboratory methods.

PP was calculated as the difference between systolic and diastolic BP at admission, and the patients were divided into two groups (group 1: PP >40 mmHg and group 2: PP ≤40 mmHg).

Median follow-up was 666±50 days for the occurrence of CV death (sudden cardiac death or death due to decompensated HF, acute coronary syndrome or arrhythmia) and heart transplantation.

Statistical analysisAll analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Continuous variables according to NYHA class or PP group were analyzed by means.

The Student's t test or Mann-Whitney test was used for binary dependent variables. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Differences between survival curves were calculated using univariate log-rank survival analysis.

ResultsDuring follow-up 914 patients in NYHA class III–IV were hospitalized, 520 in group 1 and 394 in group 2. Median follow-up was nearly two years.

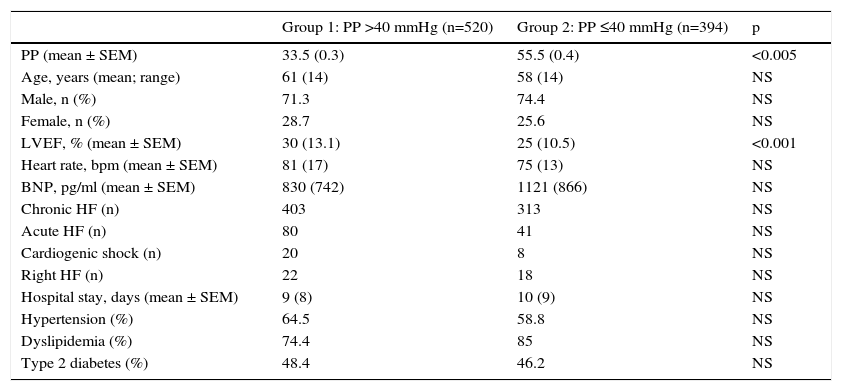

Patients’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Group 1: PP >40 mmHg (n=520) | Group 2: PP ≤40 mmHg (n=394) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP (mean ± SEM) | 33.5 (0.3) | 55.5 (0.4) | <0.005 |

| Age, years (mean; range) | 61 (14) | 58 (14) | NS |

| Male, n (%) | 71.3 | 74.4 | NS |

| Female, n (%) | 28.7 | 25.6 | NS |

| LVEF, % (mean ± SEM) | 30 (13.1) | 25 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate, bpm (mean ± SEM) | 81 (17) | 75 (13) | NS |

| BNP, pg/ml (mean ± SEM) | 830 (742) | 1121 (866) | NS |

| Chronic HF (n) | 403 | 313 | NS |

| Acute HF (n) | 80 | 41 | NS |

| Cardiogenic shock (n) | 20 | 8 | NS |

| Right HF (n) | 22 | 18 | NS |

| Hospital stay, days (mean ± SEM) | 9 (8) | 10 (9) | NS |

| Hypertension (%) | 64.5 | 58.8 | NS |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 74.4 | 85 | NS |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 48.4 | 46.2 | NS |

BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; HF: heart failure; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PP: pulse pressure; SEM: standard error of the mean.

There were no significant differences between patients with lower and higher PP. Mean age was similar and most patients were male in both groups. There were also no differences in medication or CV risk factors.

The most important difference between the groups was in left ventricular dysfunction, which was greater in patients with lower PP. Length of hospital stay was greater in group 2, although without statistically significant difference.

On Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 1), group 2 had higher mortality (38 vs. 24 patients, log-rank p=0.002).

DiscussionOur study showed that low PP predicted CV death in patients with advanced HF. Furthermore, low PP was closely associated with worsening left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).3

PP has been previously correlated with arterial compliance and with hemodynamic factors such as stroke volume and peak aortic blood flow. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction reduces stroke volume and therefore also PP and systolic BP. Several studies have shown a positive correlation between low PP and diminished cardiac index (<2.2 l/min/m2). Voors et al. reported a positive and independent association between low PP and low LVEF, and our results confirm these observations.4

There are well recognized factors that affect mortality in HF, such as older age, diabetes, renal failure, higher NYHA class, low LVEF, low peak oxygen consumption, low plasma sodium levels and high natriuretic peptides. In our study low PP and low LVEF were the most important predictors of CV death.4

The data on the relationship between PP and HF prognosis are limited and controversial. In two large trials, high PP predicted adverse CV outcomes in mild HF patients. The SAVE investigators5 showed that higher PP predicted worse outcome in patients with asymptomatic LV systolic dysfunction, and the SOLVD investigators6 reported that high PP was an independent predictor of total CV death in patients with mild HF. Other investigators showed that low PP independently predicted higher CV mortality in patients with advanced and decompensated HF, but not in patients with mild HF. Voors et al.4 proposed that low PP indicated decreased cardiac function. In another study PP only appeared to be an independent predictor of CV death in non-ischemic HF.

The differences between findings on the prognostic value of PP may be due to different characteristics of the study populations. In mild HF, a high PP is probably the result of vascular stiffening or decreased aortic elasticity, which indicates atherosclerosis and therefore a poorer prognosis, whereas in advanced HF, low PP indicates decreased cardiac function and an associated worse prognosis, as demonstrated in our study.4,5

ConclusionPP is easily calculated and can provide a clinical prognostic indicator in patients hospitalized for advanced HF.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.