Introduction: In iatrogenic or potentially reversible bradyarrhythmia, drug discontinuation or metabolic correction is recommended before permanent cardiac pacemaker (PM) implantation. These patients often have conduction system disease and there are few data on recurrence or the need for a permanent PM.

ObjectiveTo analyze the need for PM implantation in patients with iatrogenic bradyarrhythmia or bradyarrhythmia associated with other potentially reversible causes.

MethodsWe assessed consecutive symptomatic patients admitted to the emergency department with a primary diagnosis of bradyarrhythmia (atrioventricular [AV] node disease – complete or second-degree AV block (AVB) [CAVB: 2nd-degree AVB – 2:1], sinus bradycardia [SB] and atrial fibrillation [AF] with slow ventricular response [SVR]) in the context of iatrogenic causes or metabolic abnormalities. We determined the percentage of patients who required PM implantation.

ResultsWe studied 153 patients (47% male) admitted for iatrogenic or potentially reversible bradyarrhythmia. Diagnoses were SB 16%, CAVB 63%, second-degree AVB 12%, and AF with SVR 10%. Eighty-five percent of patients were under negative chronotropic therapy, 3% had hyperkalemia and 12% had a combined etiology. After correction of the cause, 55% of patients (n=84) needed a PM. In these patients the most common type of bradyarrhythmia was CAVB, in 77% (n=65) patients.

ConclusionIn a high percentage of patients with bradyarrhythmia associated with a potentially reversible cause, the arrhythmia recurs or does not resolve during follow-up. Patients with AV node disease constitute a subgroup with a higher risk of recurrence who require greater vigilance during follow-up and should be considered for PM implantation after the first episode.

Na bradidisrritmia (BD), associada a iatrogenia medicamentosa ou potenciais causas reversíveis, está recomendada a suspensão ou correção das mesmas, antes da implantação de pacemaker definitivo (PM). No entanto, estes doentes (dts) apresentam frequentemente doença do sistema de condução, existindo poucos dados relativos à recorrência de BD e à necessidade futura de PM.

ObjetivoAvaliação da necessidade de colocação de PM em dts com BD iatrogénica ou associada a outra causa potencialmente reversível.

MétodosForam avaliados dts consecutivos sintomáticos admitidos no serviço de urgência com o diagnóstico de BD (Doença do nódulo aurículo-ventricular – bloqueio aurículo-ventricular completo e bloqueio aurículo-ventricular 2.° grau (2:1); Bradicardia Sinusal (BS) e Bradifibrilhação auricular (BFA)) no contexto de iatrogenia medicamentosa ou alterações metabólicas. Foi avaliada a percentagem de dts com necessidade de colocação de PM.

ResultadosEstudaram-se 153 dts (47% sexo masculino) admitidos com BS 16%; BAVC 63%; BAV 2.° grau 12%; BFA 10%. Verificou-se iatrogenia medicamentosa em 85% dos dts, hipercaliemia em 3% e etiologia combinada em 12%. Após suspensão da «iatrogenia», 55% dos dts (n = 84) colocou PM, sendo o BAVC, o tipo de bradidisrritmia mais frequente, presente em 77% (n = 65) destes doentes.

ConclusãoEm dts admitidos com BD associada a uma potencial causa reversível, elevada percentagem de dts apresentam persistência ou recorrência do quadro com necessidade de PM. Os dts com iatrogenia associada a doença do nódulo AV constituem um subgrupo com risco de recorrência mais elevado, necessitando de maior vigilância durante o follow-up, devendo-se ponderar PM no primeiro episódio.

Iatrogenic (drug-induced) or potentially reversible bradyarrhythmia is a common but inadequately characterized clinical situation.1 The current European Society of Cardiology guidelines on cardiac pacing recommend discontinuation of iatrogenic medication or correction of the reversible cause before permanent pacemaker implantation.2,3

These patients often have underlying conduction system disease and there are few data on recurrence in this population or the need for pacemaker implantation in the future.4–6

According to published studies, around 25% of bradyarrhythmias are not caused by, but revealed by medication, and beta-blockers are the most common ‘offending’ drug involved.4

Metabolic abnormalities, particularly electrolyte imbalances, are generally benign and in most cases the resulting bradyarrhythmia can be resolved. They are therefore frequently excluded from studies of iatrogenic bradyarrhythmias.5

The present study aimed to analyze the need for permanent pacemaker implantation during hospital stay or after discharge in patients with iatrogenic bradycardia or bradycardia associated with other potentially reversible causes.

MethodsStudy populationThe sample consisted of 153 consecutive patients admitted to the emergency department over a six-year period (2010-2015) with a main diagnosis of symptomatic bradyarrhythmia (atrioventricular [AV] node disease – complete AV block (AVB) (CAVB) and second-degree AVB), sinus bradycardia (SB) and atrial fibrillation (AF) with slow ventricular response) induced by medication or metabolic abnormalities.

VariablesThe study population was characterized according to baseline characteristics, clinical features, type of bradyarrhythmia, outpatient treatment and electrolyte imbalances.

The diagnosis of second-degree AVB in this study referred specifically to 2:1 AVB; no instances of types I or II Mobitz were recorded in our sample.

Patients with AF and CAVB were included in the CAVB group, the AF group consisting only of patients with slow ventricular response and no AV conduction disorder.

The following drugs were considered as possible iatrogenic agents: beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and antiarrhythmic agents. When assessing the impact of drug therapy on the need for pacemaker implantation, amiodarone was grouped with digoxin in order to obtain a larger sample of antiarrhythmics to compare with beta-blockers, bearing in mind the frequency with which these anti-arrhythmics are prescribed (alone or in combination) in the age-group under study, unlike sotalol and propafenone, which are used less often.

The only metabolic disorder included was hyperkalemia, defined as serum potassium >6.5 mEq/l.

Study endpointThe study endpoint was the need for pacemaker implantation during hospital stay or after discharge following drug discontinuation and/or correction of electrolyte imbalance, in the overall population and for each type of bradyarrhythmia.

Follow-upThe mean follow-up was 24±2 months, during which recurrence of clinically significant and symptomatic bradyarrhythmia was recorded.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 for Windows 8. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the Student's t test. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute number and/or percentage and compared with the chi-square test. Associations were considered significant for p-values <0.05.

ResultsThe baseline characteristics of the overall population and by type of bradyarrhythmia are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Baseline characteristics of the overall population and by type of bradyarrhythmia.

| Population (n=153) | SB (n=24) | CAVB (n=97) | 2nd-degree AVB (n=18) | AF with SVR (n=14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 82±11 | 80±12 | 84±10 | 78±13 | 82±7 |

| Male gender | 47% (72) | 42% (10) | 44% (43) | 61% (11) | 64% (n=9) |

| Personal history | |||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 26% (39) | 8% (2) | 27% (26) | 22% (4) | 50% (7) |

| Heart failure | 9% (13) | 17% (4) | 6% (6) | 0 | 21% (3) |

| Hypertension | 92% (141) | 92% (22) | 93% (90) | 89% (16) | 93% (13) |

| Diabetes | 29% (44) | 17% (4) | 32% (31) | 28% (5) | 29% (4) |

| Dyslipidemia | 41% (62) | 38% (9) | 40% (37) | 44% (8) | 43% (6) |

| Renal failure | 19% (29) | 25% (6) | 18% (17) | 11% (2) | 29% (4) |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Syncope | 43% (66) | 33% (8) | 52% (50) | 39% (7) | 7% (1) |

| Dizziness | 39% (25) | 21% (5) | 23% (22) | 28% (5) | 50% (7) |

| Prostration | 10% (16) | 13% (3) | 8% (8) | 1% (1) | 21% (3) |

| Fatigue | 20% (30) | 21% (5) | 14% (14) | 4% (4) | 7% (1) |

| Non-specific malaise | 1% (2) | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 14% (2) |

| Chest pain | 2% (3) | 4% (1) | 0 | 6% (1) | 7% (1) |

| Dyspnea | 2% (3) | 4% (1) | 2% (2) | 0 | 0 |

| In-hospital death | |||||

| Before PM | 2% (3) | 0 | 3% (3) | 0 | 0 |

| After PM | 0.6% (1) | 0 | 1%(1) | 0 | 0 |

| Need for temporary pacing | 28% (43) | 4% (1) | 42% (41) | 5% (1) | 0 |

| Drug therapy | |||||

| BB | 32% (49) | 17% (4) | 35% (34) | 44% (8) | 21% (3) |

| CCB | 10% (16) | 8% (2) | 9% (9) | 22% (4) | 0 |

| AA | 13% (20) | 13% (3) | 13% (13) | 22% (4) | 0 |

| Digoxin | 4% (6) | 8% (2) | 3% (3) | 0 | 7% (1) |

| Sotalol | 1% (2) | 0 | 2% (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Propafenone | 3% (4) | 4% (1) | 2% (2) | 6% (1) | 0 |

| BB+sotalol | 5% (7) | 4% (1) | 4% (4) | 0 | 14% (2) |

| BB+propafenone | 2% (3) | 0 | 2% (2) | 0 | 7% (1) |

| BB+AA | 7% (10) | 17% (4) | 5% (5) | 0 | 7% (1) |

| BB+digoxin | 1% (2) | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 0 |

| BB+CCB | 2% (3) | 4% (1) | 2% (2) | 0 | 0 |

| BB+AA+digoxin | 0.6% (1) | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 0 |

| CCB+sotalol | 0.6% (1) | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Digoxin+AA | 3% (4) | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 21% (3) |

| BB+CCB+digoxin | 0.6% (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7% (1) |

| CCB+AA+digoxin | 0.6% (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7% (1) |

| Electrolyte imbalance | |||||

| Hyperkalemia | 3% (4) | 0 | 3% (3) | 6% (1) | 0 |

| Combined etiology | |||||

| Drug therapy+electrolyte imbalance | 12% (19) | 25% (6) | 12% (12) | 0 | 7% (1) |

AA: aldosterone antagonist; AF with SVR: atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response; BB: beta-blocker; BS: sinus bradycardia; CAVB: complete atrioventricular block; CCB: calcium channel blocker; PM: pacemaker implantation.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to pacemaker implantation.

| PM during hospitalization (n=61) | PM not required (n=92) | p | Total PM (n=84) | PM not required (n=69) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 82±12 | 82±10 | NS | 82±11 | 82±10 | NS |

| Male gender | 49% (30) | 46% (42) | NS | 49% (41) | 45% (31) | NS |

| Personal history | ||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 25% (15) | 26% (24) | NS | 29% (24) | 22% (15) | NS |

| Heart failure | 3% (2) | 12% (11) | NS | 5% (4) | 13% (9) | NS |

| Hypertension | 90% (55) | 93% (86) | 0.001 | 87% (73) | 99% (68) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes | 25% (15) | 32% (29) | NS | 31% (26) | 26% (18) | NS |

| Dyslipidemia | 48% (29) | 36% (33) | NS | 46% (39) | 33% (23) | NS |

| Renal failure | 5% (3) | 28% (26) | 0.001 | 6% (5) | 35% (24) | 0.001 |

| Need for temporary pacing | 3% (2) | 22% (20) | NS | 27% (23) | 29% (20) | NS |

| Type of bradyarrhythmia | ||||||

| SB | 2% (1) | 25% (23) | 0.001 | 4% (3) | 30% (21) | 0.001 |

| CAVB | 77% (47) | 54% (50) | 77% (65) | 46% (32) | ||

| 2nd-degree AVB (2:1) | 18% (11) | 8% (7) | 17% (14) | 6% (4) | ||

| AF with SVR | 3% (2) | 13% (12) | 2% (2) | 17% (12) | ||

AVB: atrioventricular block; AF with SVR: atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response; CAVB: complete atrioventricular block; PM: pacemaker; SB: sinus bradycardia.

We studied 153 patients, mean age 82±11 years, 47% male. Of these, 63% (n=97) presented CAVB, 16% (n=24) sinus bradycardia, 12% (n=18) second-degree AVB and 9% (n=14) AF with slow ventricular response. The most common form of presentation was syncope, seen in 42% (n=64) of patients.

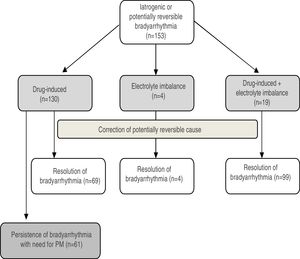

Potentially reversible etiologies associated with electrocardiographic abnormalities were attributed to drug therapy alone in 85% (n=130), to drug therapy associated with electrolyte imbalances in 12% (n=19), and to electrolyte imbalances alone in 3% (n=4) (Figure 1).

Of patients with purely drug-induced bradyarrhythmia, 38% (n=49) were taking beta-blockers, 15% (n=20) amiodarone, 12% (n=16) calcium channel blockers, 5% (n=6) digoxin, 2% (n=2) sotalol and 3% (n=4) propafenone, while 25% (n=33) were on two or three drugs (Table 1).

Permanent pacemaker implantation was needed in 55% (n=84) of the population, during the first hospitalization in 40% (n=61). Resolution of bradyarrhythmia was achieved in 15% (n=23) of the population following drug discontinuation or correction of electrolyte imbalance, but these patients suffered another episode of bradycardia without an apparently reversible cause and underwent pacemaker implantation.

Of the patients requiring a pacemaker, CAVB was the most frequent type of bradyarrhythmia, found in 77% (n=65) of cases, followed by second-degree AVB in 17% (n=14) (Table 2).

Of patients under drug therapy, 62% (n=81) required pacemaker implantation despite discontinuing therapy. Drug therapy in isolation was statistically significantly associated with less likelihood of resolving the bradyarrhythmia compared to other potentially reversible causes (Table 3).

Etiology of bradyarrhythmia according to pacemaker implantation.

| Total PM | Drugs | Drugs+electrolyte imbalance | Electrolyte imbalance (hyperkalemia) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 81 | 2 | 1 | 0.001 |

| No | 49 | 17 | 3 |

| PM during hospitalization | Drugs | Drugs+electrolyte imbalance | Electrolyte imbalance (hyperkalemia) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| No | 69 | 19 | 4 |

PM: pacemaker implantation.

Of the patients who received pacemakers, 46% were medicated with beta-blockers, 24% with amiodarone and/or digoxin and 12% with calcium channel blockers, all without statistical significance (Table 4).

Need for pacemaker implantation according to drug therapy.

| PM during hospitalization (n=61) | Total PM (n=84) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers (n=49) | 48% (n=29) | 46% (n=39) | NS |

| Amiodarone and/or digoxin (n=30) | 25% (n=15) | 24% (n=20) | NS |

| CCBs (n=16) | 11% (n=7) | 12% (n=10) | NS |

CCBs: calcium channel blockers; PM: pacemaker implantation.

Temporary pacing was required in 28% (n=43) of the population, mainly those with CAVB, of whom 53% (n=23) required permanent pacemaker implantation.

Patients in whom bradyarrhythmia was resolved without need for pacemaker implantation were significantly more likely to present renal failure (24 vs. 5; p=0.001). Most patients who did not need pacemaker implantation had hypertension (Table 1).

Four patients died during hospitalization, three before pacemaker implantation and one after. No deaths were recorded in patients after discharge without pacemaker implantation.

DiscussionIn this population, most patients required pacemaker implantation after iatrogenic drug discontinuation and/or correction of potentially reversible causes of bradyarrhythmias.

The proportion of patients with atrioventricular block who discontinue drug therapy and still need pacemaker implantation is unknown, as is the prognosis of these patients after hospital discharge without a pacemaker.2 There are few data on the situation concerning patients with bradyarrhythmias due to metabolic disorders, since their apparently benign course means they are excluded from most studies on iatrogenic bradyarrhythmias.

Although the number of patients with hyperkalemia in our study was low, electrolyte imbalances were associated with iatrogenic bradyarrhythmias in 75% of cases, in which normalization of heart rhythm was achieved after electrolyte correction, only one patient requiring pacemaker implantation. This is an indication of the benign nature of this condition, in contrast to the 96% (n=81) of patients under drug therapy requiring pacemaker implantation.

In a quarter of patients with drug-related bradycardia, the arrhythmia is not caused, but revealed by medication, of which beta-blockers are the most common ‘offending’ drugs.4

In a study by Zelter et al., 56% of patients whose AVB resolved after drug discontinuation presented recurrence of bradyarrhythmia,6 while in Knudsen et al. the corresponding figure was 25%.2

In this population, 25% of patients discharged without a pacemaker following apparent resolution of bradyarrhythmia presented recurrence of electrocardiographic abnormalities with need for pacemaker implantation during follow-up.

Studies in the literature indicate that drugs at therapeutic doses do not usually cause significant bradycardia in patients without structural heart disease, but when there is latent sinus node or AV node disease, drug therapy can trigger bradyarrhythmias.4–6

Although not reaching statistical significance, bradyarrhythmias were less likely to be resolved by discontinuation of beta-blockers than other antiarrhythmics, as shown in other studies.1,2,5

Advanced age and a history of ischemic heart disease are predictors of arrhythmic risk, but in our population the rate of pacemaker implantation was no higher in these patients, even though the mean age of the study population was over 65 years and 26% had coronary artery disease.1,5

Bradycardia in the context of AF is relatively common. According to some studies, pacemaker implantation is required in 1.4% of patients taking amiodarone and 2.5% of those taking sotalol. In a study by Israel et al., among 78 patients with a DDDR system implanted for symptomatic bradycardia and paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation, the bradycardia was drug-induced in 33%.1,5 In our study, only two patients with AF with slow ventricular response required pacemaker implantation after drug discontinuation or correction of a potentially reversible cause, which suggests that this condition is more amenable to resolution, and hence more benign, than AV node disease. None of the patients with AF with slow ventricular response who were discharged without a pacemaker presented a new episode of arrhythmia requiring pacemaker implantation during follow-up.

Bradyarrhythmia was less likely to be resolved in cases of AV node disease (CAVB and second-degree AVB), with 55% (n=79) of patients requiring pacemaker implantation. Of those with AV node disease who were discharged without a pacemaker, 37% (n=21) presented recurrence during follow-up. This poses the important question as to whether pacemaker implantation should be considered immediately after the first episode of bradycardia. Various authors have commented on this issue, to which there is as yet no definitive answer. Several studies have shown that AV node disease does not occur in structurally normal hearts and that even when it is induced by drug therapy, there is underlying conduction system disease.2,4

In the present study, most patients with renal failure achieved resolution of bradyarrhythmia and hence did not need pacemaker implantation. The literature shows that permanent pacing is required more often in patients with chronic renal failure than in the general population. This could not only be the consequence of hyperkalemia but might also reflect increased conduction system disease due to abnormalities in calcium metabolism leading to fibrosis and myocardial calcification.7 The level of severe renal failure in our population was low, and as a result resolution of bradyarrhythmia could be achieved by correcting the iatrogenic cause (drug therapy and/or electrolyte imbalance).

Hypertension is a common cardiovascular comorbidity in the general population as well as in our study. Depending on its severity and duration, hypertension can induce cardiac remodeling, which may affect electrical activity, leading to rhythm disturbances, particularly supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias. There have been few multicenter studies on AV conduction disorders associated with hypertension.8

In our study, hemodynamic instability and consequent need for temporary pacing were not significantly associated with greater need for permanent pacemaker implantation, although a larger sample might enable more definite conclusions to be drawn. Hemodynamic instability was not associated with recurrence of bradyarrhythmia.

The three patients who died during hospitalization required temporary pacing due to hemodynamic instability, but did not respond. The deaths were not considered to be a complication of the procedure. These patients were old (aged over 80 years) and consequently had multiple comorbidities.

Although there were recurrences of bradycardia, there were no deaths during follow-up, which is an indication of the safety of current clinical practice, as most patients were discharged without a pacemaker following resolution of the iatrogenic cause of their bradyarrhythmia.

LimitationsThe study's retrospective nature and its small sample size are its main limitations. In addition, the relatively short follow-up period may have led to the frequency of bradycardia being underestimated.

We were unable to analyze the dosage of each drug associated with bradyarrhythmias for every patient, since this was not recorded at admission in all cases. Information on escape rhythm and QRS width was also incomplete, the latter because digitally stored ECGs were not available throughout the study period.

Patients did not undergo 24-hour Holter outpatient ECG monitoring, which might have identified asymptomatic bradycardia or AVB in some cases. Only symptomatic brady-arrhythmias with indication for permanent pacemaker implantation were assessed in this study.

ConclusionsIn a high percentage of patients admitted with bradyarrhythmia associated with a potentially reversible cause, mainly drug-induced, the arrhythmia recurs or does not resolve, requiring placement of a permanent pacemaker.

Patients with AV node disease constitute a subgroup with a higher risk of recurrence who require greater vigilance during follow-up and should be considered for pacemaker implantation after the first episode.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Duarte T, Gonçalves S, Sá C, Marinheiro R, Fonseca M, Farinha J, et al. Bradidisrritmia puramente iatrogénica…existe?. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:105–111.